Native Americans visited colonial cities from New Orleans to Montreal, Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Charleston, and ports and towns in between. Historians have traditionally focused on the outcomes of “the chiefs now in this city,” namely, treaties. Colin Calloway’s book focuses our attention before and after those formal negotiations, and asks questions like: What did Indian folks see, what did they smell, eat, drink? Where did they stay, and what did they think about it?

The answers help us rediscover an urban social world that Native people participated in outside of their own hometowns.

The book’s wide-ranging evidence disproves a common perception that Native Americans don’t have cities, and cities don’t have Native people. In the past and often in the present, “cities represented progress and modernity; Indians represented an unchanging and primitive past.” This book demonstrates that rather than fleeing these footholds of European expansion, Native people often flocked to them.

The book’s subtitle is “Indians and the Urban Frontier in Early America.” Both urban and frontier are debated concepts. For this work, however, the words work to invert the usual viewpoints we use.

In essence, what is urban, or a frontier, is in the eye of the beholder. Calloway’s survey of early American towns re-integrates Native folks into the past. Insofar as colonists tended to see frontiers and Indians as intertwined concepts, Calloway tells us, “One might argue that Indians saw a frontier as anywhere colonists were.” Although a “frontier” suggests a demarcation line, the idea quickly gives way to cities as hubs, “a zone of cultural interaction,” or “points of convergence and connection.”

The work is arranged thematically around chapters that detail common experiences. These include Indigenous groups arriving in town, lodging, dining, drinking, attending performances and performing, health, and leaving town. Chapter three, “The Other Indians in Town,” for instance, explores the anonymous Native people living and working in early American towns. It is among the book’s best. Whereas tribal delegations punctuated the calendar of most colonial towns, “other Indian people,” Calloway reminds us, “attracted much less attention, frequented cities more regularly, and in some cases lived and worked there.”

Native Americans tour Philadelphia, 1800.

Montreal’s French population reached parity with Indigenous residents by 1700; in that period, about 13 per cent of households included enslaved Native people. Boston newspapers ran advertisements seeking runaway Indian slaves. Native food vendors participated in the “French Market” of New Orleans. Historians have tended to ignore and render invisible these prominent segments of colonial urban societies. Instead, they have told the stories of the noticeable visitors attending operas and state dinners.

Walking the streets of any eastern colonial city—Williamsburg, New York, Detroit, Baltimore, and the like—one could expect to see Native people walking there too. Iroquois diplomats and traders visited Albany constantly. Many Native women, their husbands gone to sea, worked in New England towns such as Boston. Charleston and Savannah authorities regulated the numbers of Cherokee basket-sellers through a pass system. A stream of tribal delegates came and went from Philadelphia, particularly in its days as the federal capital city in the late eighteenth century.

In one interesting case, when Shawnees visited a museum in Philadelphia, they ran into another tour group, these from the Chickasaw, Cherokee, and Choctaw nations. Colonial governors and the first several American presidents expected to host Native visitors at dinner frequently, sometimes several different delegations in a single week.

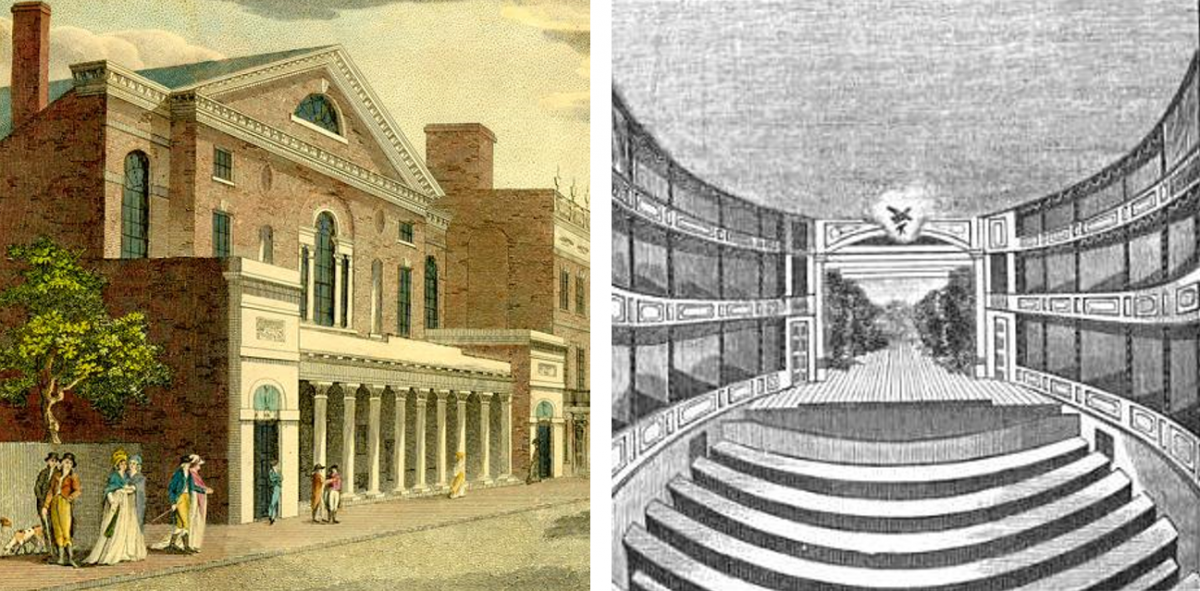

The exterior (left) and interior (right) of the New Theatre in Philadelphia where Native Americans took in performances.

This is a book that only an established scholar of colonial Indian Country could write. It is Calloway’s eleventh (by my count) monograph, and he has also published a highly used Native American history textbook and a prize-winning synthesis of early Western American history. In short, Calloway is among the deans of eighteenth century Native American history, and he has put his extensive research notes to good use here.

While not long, the book is dense with examples. Evidence takes center stage, frequently in lists of quotations. Calloway has done us a service in the extent of sources pulled together. Microhistories of particular Native trips, or Native people in a specific city, can be wonderful. It is something else, I think, to integrate the commoner and more frequent trips made within North America.

For all of the order Calloway manages to impose on the past (and it was a mammoth task to organize the evidence in thematic chapters) one of the greatest strengths of the book is how it underscores the messiness of intercultural encounters. Indians and settlers knew each other well enough; they were not strangers. Yet, they were not beyond surprise or learning, either.

A prominent, “messy” example—Teedyuscung—illustrates a range of interactions and convergences. Teedyuscung was a Delaware Indian leader critical to Pennsylvania and Delaware Nation politics. He also had an extensive social life in Philadelphia, although he did not live there. He “always regarded himself as at home” with the Quaker family of Isaac Norris and also was “constantly nurs’d and Entertain’d at” the house of Israel Pemberton in that city.

Teedyuscung spoke English and was fond of rum, and he wore English or French gentleman’s attire in colonial towns. Apparently, he was so fond of strong spirits while in town that his wife Elizabeth preferred to stay at the Crown Tavern in Bethlehem rather than suffer his behavior in Philadelphia. This was a man who traveled with an escort of Pennsylvania soldiers; who insisted on not only an interpreter but a clerk at conferences; who visited Philadelphia for business, diplomacy, and pleasure. Teedyuscung was told by the governor of Pennsylvania that, given an upcoming meeting in Philadelphia, he better not come after all. Smallpox had arrived there. The talks could take place to the North of the city instead, “where they might Escape the Infection and be well Entertained.”

Native Americans tour Philadelphia near the New Lutheran Church, 1800.

Teedyuscung died in a suspicious fire that engulfed his home city in the Wyoming Valley during a dispute between rival land companies. His life was fully entangled with Philadelphia; it would be impossible to understand him without knowing his experiences there. The “Indian chief” who signed treaties thus becomes inseparable from the man who wore a French waistcoat to dinner and asked about the health of the Governor of Pennsylvania’s wife.

By shining a light on hundreds of people making hundreds of trips in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, this book will open the door for further work. (I found myself wanting to re-examine trips I thought I understood, such as the Myaamia leader Little Turtle’s visit to Philadelphia in 1798, which is one of those hundreds.) Researchers following Calloway will be able to use this book as a road map. By its end, Calloway has painted a kind of aggregate portrait, a composite of what Indian people did while visiting cities in colonial eastern North America. No longer should we be surprised by Indigenous presences in colonial spaces.