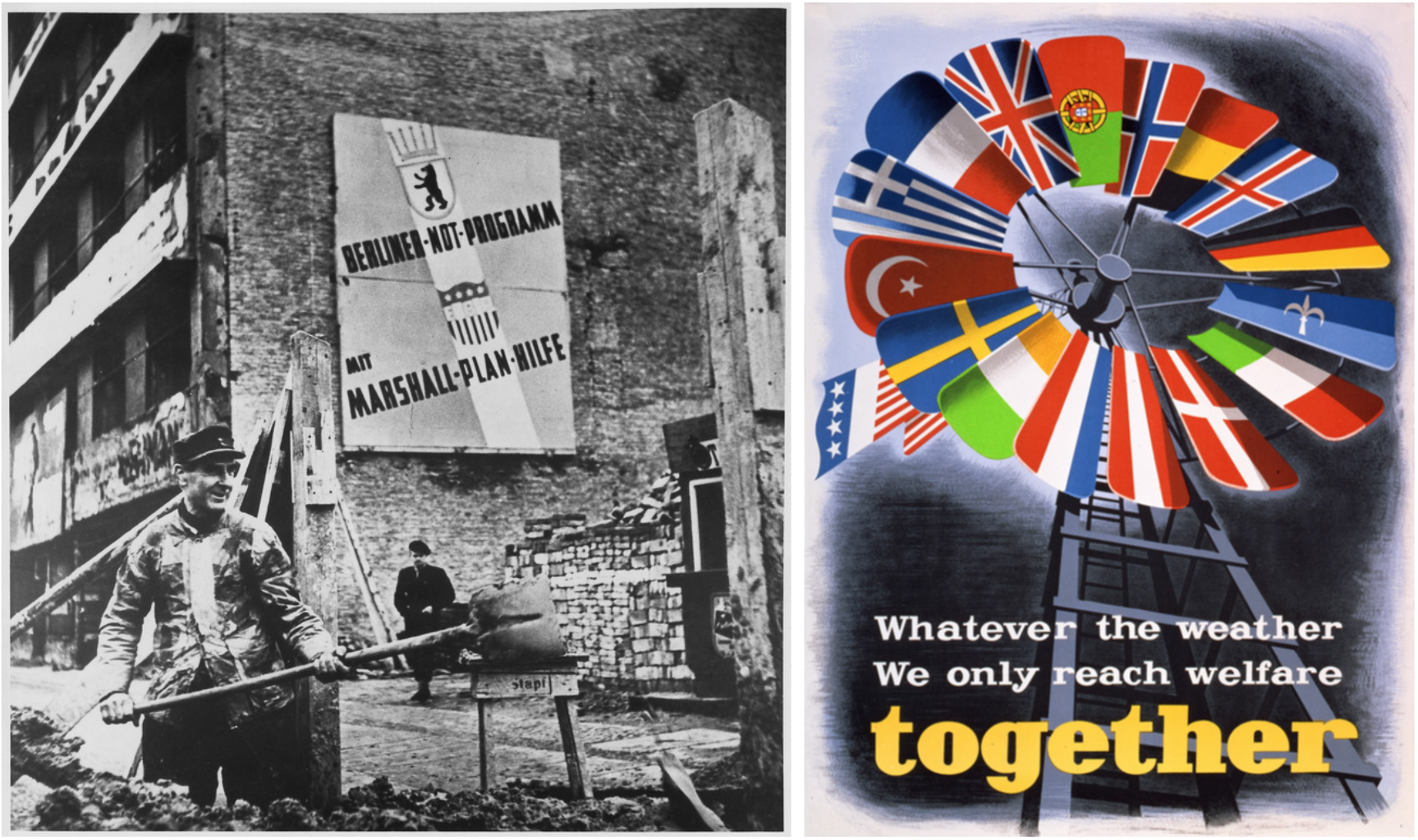

President Harry Truman signed the European Recovery Act into law on April 3, 1948. The Marshall Plan, as it’s more commonly known, was intended to revive the economies of war-torn Western Europe. Extending nearly $13 billion to primarily France, the United Kingdom, Italy, and West Germany, the program was an ambitious foreign aid effort and an unprecedented display of U.S. global power.

The Marshall Plan diverged from a long-standing U.S. foreign policy tradition of cautious isolationism. The rationale of abstaining from foreign conflicts and entangling alliances to preserve national autonomy had shaped American policy since George Washington’s famous Farewell Address in 1796. Even President Woodrow Wilson’s League of Nations, after all, was defeated in 1920 by a Senate majority that viewed large-scale security investments in Europe as an infringement on American sovereignty.

Most U.S. legislators did not openly acknowledge that the United States could not guarantee its own political and economic security until 1945, but the Great Depression and Second World War made the connections between American and European stability clear. By the time the European Recovery Act arrived on Truman’s desk, even ardent isolationists such as Congressman Hamilton Fish and Senator Robert Taft had endorsed it.

U.S. policymakers’ newly globalized understanding of national security acutely shaped their assessment of Europe’s worsening financial and humanitarian situation in the years after the war. Between 1946 and 1947, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Policy Planning Staff, and the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee reported on the continent’s dire economic state, exacerbated by harsh winters and dismal supply of food and fuel.

Officials soon realized that loans from newly-minted international financial institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, were simply not enough to return Europe to its pre-war industrial power.

Fears of a second great depression weighed heavily on the minds of Washington’s top diplomats and generals as they designed more forceful, invasive measures to resuscitate Europe’s ailing economies. Officials worried that without seismic levels of foreign aid and advising, both European and American capitalism would falter.

On April 2, 1948, Congress approved the European Recovery Act, putting the European Recovery Program (ERP) into action. The program included fostering participating countries’ self-sufficiency, maximizing their industrial output, facilitating the cooperation between inter-state economies, and increasing the amount of dollar reserves available for European countries to trade with the United States and the wider world.

To help implement the ERP’s goals, the U.S.-managed Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA) and the European-based Organization for European Economic Cooperation were created. From 1948 to 1951, the ECA provided extensive grants to jumpstart Western European agriculture and manufacturing. Britain and France received around 43 percent of all Marshall funds to purchase American raw materials necessary for reconstruction.

Additionally, the ECA, under the supervision of Averell Harriman, oversaw a range of other infrastructural projects. These included everything from rebuilding the Corinth canal in Greece to modernizing mines in Turkey.

The ECA also focused its attention on industrial centers in Germany's western zones. London and Paris were distressed by the idea of a reinvigorated Germany, but U.S. planners understood that German coal and steel production were vital to Europe’s recovery. ERP efforts to create a German economy committed to capitalism, however, hardened early divisions between Western- and Soviet-occupied lands.

Anxieties about the status of liberal capitalism were inextricable from Washington’s convictions that an economically weak Western Europe was vulnerable to communist inroads. Moscow’s frightening specter became a primary motivator for ERP congressional supporters and planners alike.

Secretary of State George Marshall, after his meeting with Stalin in early 1947, was convinced that the Soviet Premier was waiting for conditions in Western Europe to further deteriorate before orchestrating a mass power grab. Upon returning to Washington, Marshall immediately instructed the Policy Planning Staff and its head, George Kennan, to devise a pro-capitalist foreign aid program.

While Marshall famously declared before Harvard University’s 1947 graduating class that the Marshall Plan was “not directed against any country,” this statement was less a genuine olive branch to the Soviet Union than a shrewd PR tactic. As State Department USSR expert Charles Bohlen candidly admitted, “we gambled that the Soviets would not [join], and therefore we could gain prestige by including all Europeans and let the Soviet Union bear the onus for withdrawing.”

Similar to Marshall, Kennan firmly believed that the “economic maladjustment” of postwar Europe made it “vulnerable to exploitation by any and all totalitarian power.” He consistently pushed the ERP as a form of containment that would marginalize the Soviets and their Eastern sphere of influence.

Far from a de-politicized aid effort, the Marshall Plan was founded on the ideological conviction that the growing spread of Soviet Communism posed an existential threat to European and American societies and had to be thwarted.

With the War in Ukraine now in its second year, leaders across the world have looked to the Marshall Plan as a guidebook for restoring the country’s infrastructure and economic life. As German Chancellor Olaf Scholz declared to EU leaders, their task is “nothing less than creating a new Marshall Plan for the 21st century.” Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has also pushed this idea. In a video telegram, Zelensky championed “a new Marshall Plan for Ukraine" and insisted that other countries follow suit.

These encouraging ideas about a “Marshall Plan for Ukraine” focus on the program’s undeniable successes in saving a war-ravaged Europe from financial devastation and catastrophic human suffering. However, in underscoring its accomplishments, the latest references to the Marshall Plan neglect its more unsavory consequences. Although it effectively promoted Western Europe’s stability, the Plan excluded competing political-economic ideologies from assisting or receiving aid. It severely aggravated U.S.-Soviet tensions and removed the prospect of genuine European peace for nearly fifty years.

At once a cooperative humanitarian aid effort and an aggressive Cold War ploy, the Marshall Plan's reputation as a model agenda for postwar peace is not as clear-cut as it often appears. The program’s complex and contradictory legacy looms heavily over the present war in Ukraine. It is this legacy that those calling for a “new Marshall Plan” will have to consider.

![]()

Want to Learn More About the Marshall Plan?

Benn Steil. The Marshall Plan: Dawn of the Cold War. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018.

Benn Steil, "No Marshall Plan for Ukraine." Foreign Affairs, May 13, 2022.

Diane B. Kunz, "Marshall Plan Commemorative Section: The Marshall Plan Reconsidered: A Complex of Motives." Foreign Affairs, April 1, 1997.

Melvyn P. Leffler. “The United States and the Strategic Dimensions of the Marshall Plan.” Diplomatic History 12, no. 3 (1988): 277-306.