Saber-rattling between the current U.S. administration and the North Korean regime and an errant incoming missile alert in Hawaii have focused America’s attention on how the country would respond to a nuclear attack for the first time since the end of the Cold War.

In the twentieth century, the U.S. federal government established organizations to prepare the public for the possibility of such an attack. These efforts, broadly known as civil defense, consisted of all measures designed or undertaken to protect the civilian population from enemy attack.

During World War II, civilian defense personnel rarely found their efforts in demand for anything beyond practice drills. At the time the United States Army Air Forces dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, the United States had an atomic monopoly. But, as nuclear weapons and delivery systems increased in destructiveness and accuracy over the ensuing decades of the Cold War, civil defense efforts waxed, waned, and ultimately failed to provide a credible means to protect civilians from the effects of attack.

Almost 75 years after the first use of an atomic weapon, American civilians still have few protective measures from nuclear attack. Civil defense’s lasting legacy is little more than faded fallout shelter signs and the wail of emergency sirens more commonly used for tornadoes than incoming nuclear attack.

1. 1949 – Stalin and the Bomb

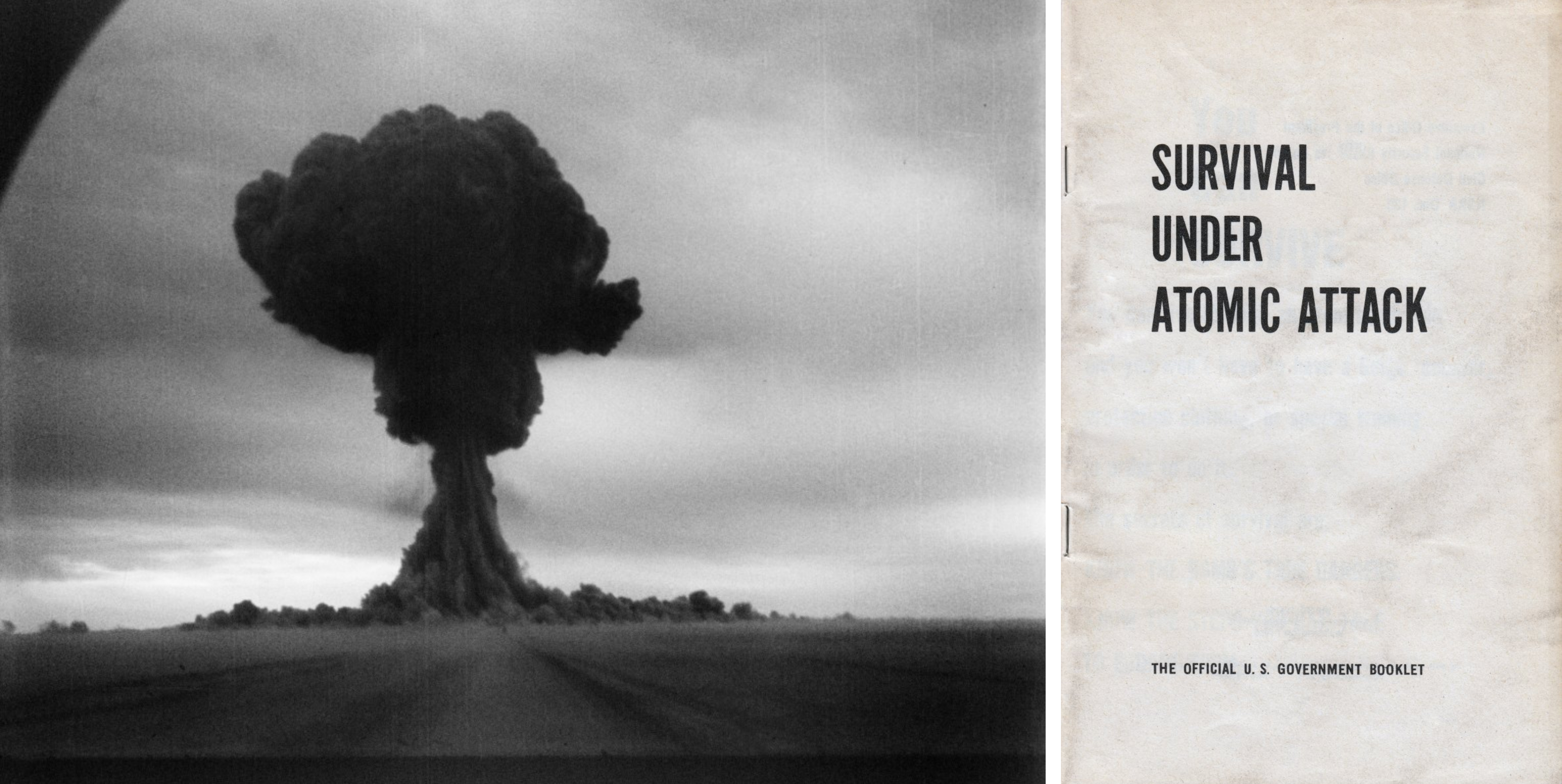

Detonation of Joe-1, the first Soviet atomic bomb, in August 1949 (left), and a 1950 government issue booklet Survival Under Atomic Attack (right).

Postwar federal civil defense planning efforts produced various reports but no permanent organization, and there was little urgency to do much more. Then in August 1949, the Soviet Union under General Secretary Joseph Stalin successfully tested its first atomic bomb. Shortly thereafter, China fell to Communist forces and war broke out on the Korean peninsula. The Cold War turned hot and Americans increasingly clamored for a renewed focus on civil defense.

In short order, President Truman authorized research into thermonuclear weapons, an expansion of the nation’s armed forces, and signed legislation establishing the Federal Civil Defense Administration. The new federal civil defense effort did little to bring immediate protection for worried citizens, however. Aside from guidance and coordination, responsibility for civil defense efforts fell on the shoulders of states and local governments, not the Federal agency.

2. 1952 – Bert the Turtle Says “Duck and Cover!”

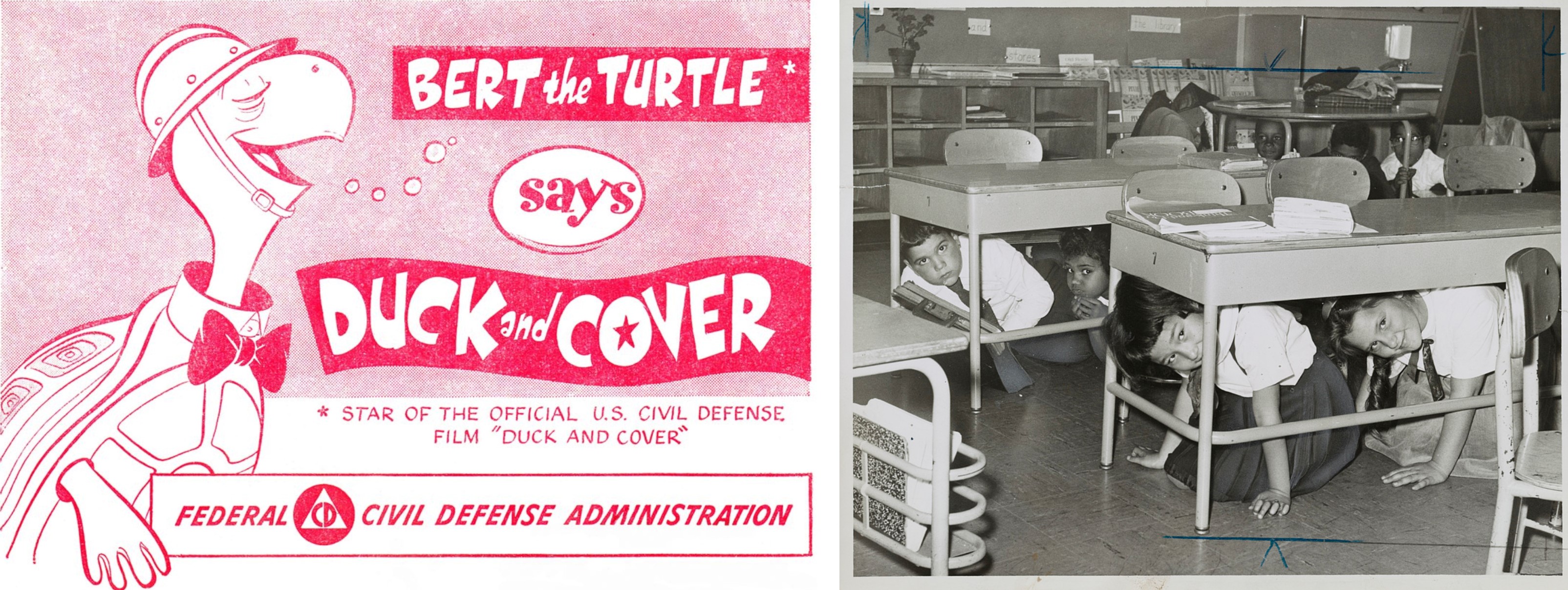

Image from the 1952 comic book Bert the Turtle Says Duck and Cover (left), and school children practicing a "take cover" drill in 1962 (right).

In January 1952, federal civil defense officials introduced American schoolchildren to Bert the Turtle. In a comic book and later an animated cartoon, Bert urged children to “duck and cover” and to shelter under a projective “shell” such as a wooden desk, wall, or in a ditch when they saw the flash of an atomic bomb. It was the bomb flash, blast, heat, and flying debris that could injure people. The danger of radiation was never mentioned.

While President Harry Truman supported an effort to build public shelters, Congress balked at the construction costs. Civil defense information campaigns urged civilians to educate themselves to cope with the immediate blast of an atomic bomb and prepare for evacuation of urban areas if needed. For the majority of Americans, confidence in the nation’s military to stop enemy attacks seemed the best defense. Today Bert is a cultural icon and a source of ironic amusement, and “duck and cover” represents the futility of civil defense guidance against atomic bombs.

3. 1954 – Castle Bravo and Fallout

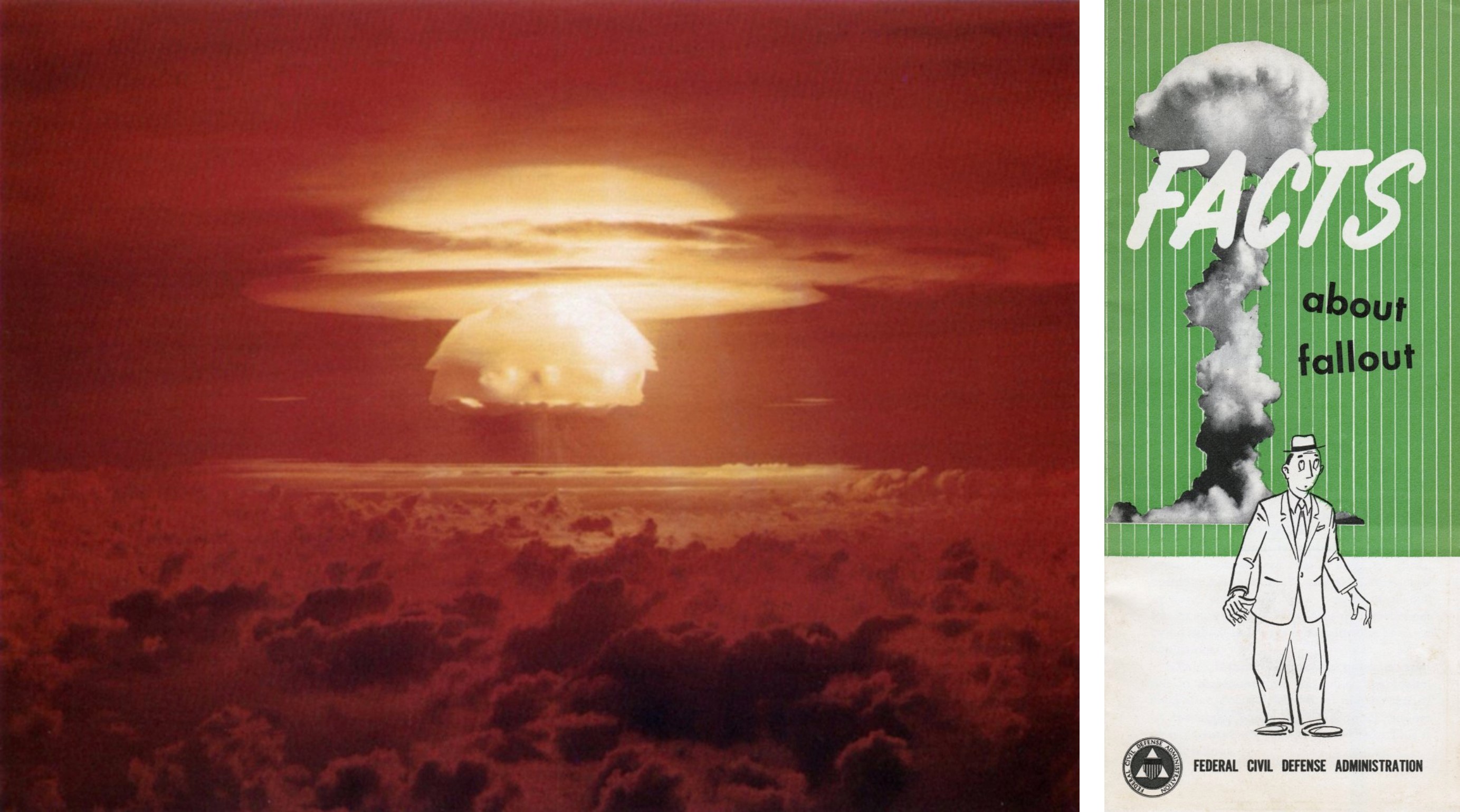

The detonation of the Castle Bravo thermonuclear bomb (left), and informational survival pamphlets Facts about Fallout (right).

The United States won the race to develop a thermonuclear weapon, detonating a device in the South Pacific in November 1952. In March 1954, an improved, aircraft-deliverable thermonuclear bomb detonated on Bikini Atoll. The blast, code-named Castle Bravo, unleashed a force equivalent to 15 million tons of TNT and produced a mushroom cloud 62 miles in diameter.

Radioactive fallout resembling snow and enveloping 7,000 square miles of ocean over 280 miles from ground zero fell from that cloud. The atomic snow fell on Americans, Marshall Islanders, and the crew of a Japanese fishing vessel. The fishermen returned to Japan suffering from radiation poisoning, shocking the world and civil defense officials with this previously unknown threat. Now anyone on earth, even thousands of miles from the site of a blast, could be killed or injured by nuclear weapons.

With “duck and cover” impractical and blast shelters too expensive, civil defense officials turned to a policy of evacuation on notice of inbound enemy bombers—what one historian called the policy of “run like hell.”

4. 1957-1958 – Sputnik and Private Shelters

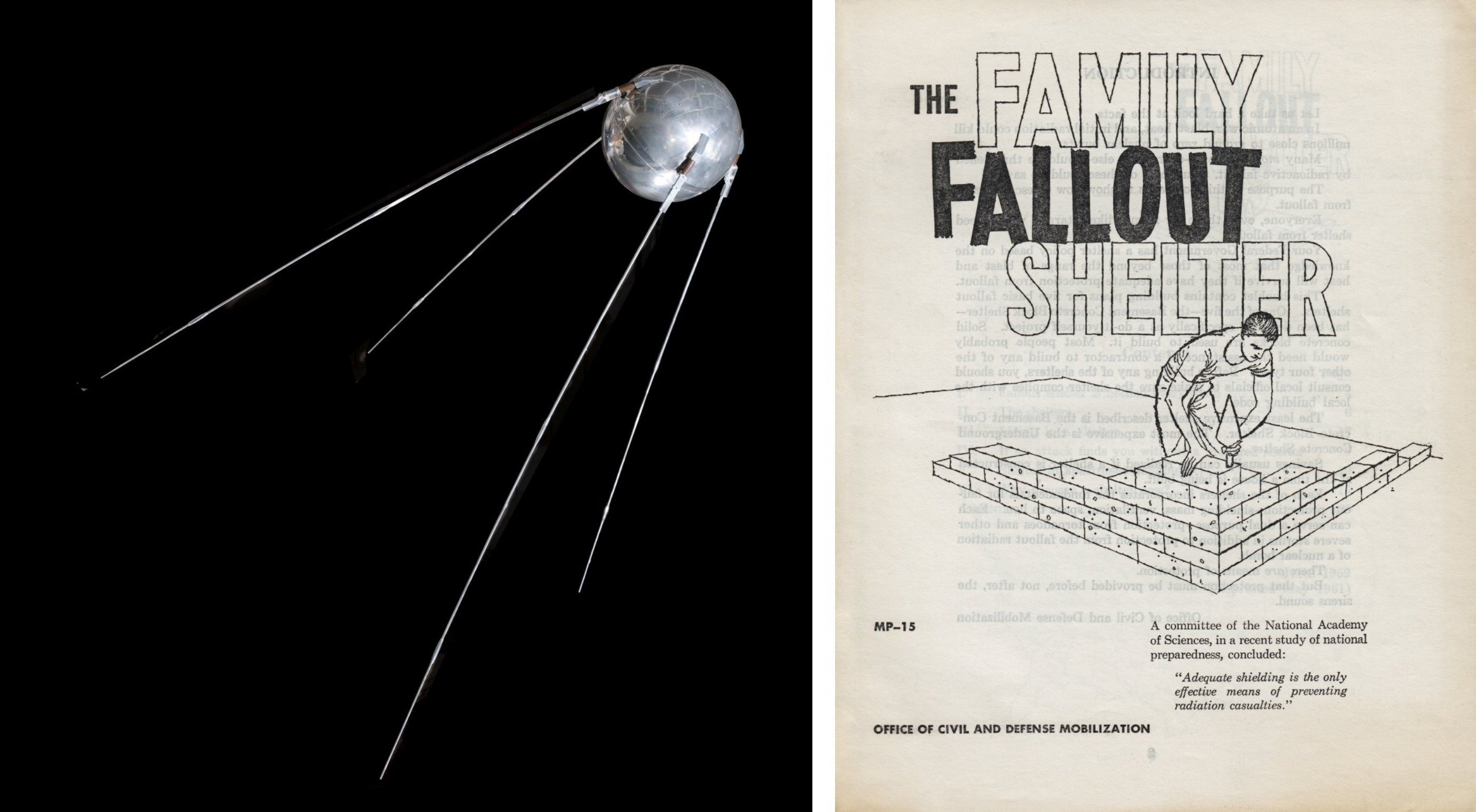

A replica of Sputnik 1 (left), and the cover of the informational booklet The Family Fallout Shelter (right).

Even with the new threat of fallout, federal civil defense officials failed to convince Congress to fund a national shelter network to protect against blast, heat, and radiation. In 1957, President Dwight Eisenhower requested a study of various shelter options. A subsequent report concluded that the civil defense measures in place would not provide protection for the civilian population and recommended funding and establishing a nationwide fallout shelter program.

Concurrently, in October 1957 the Soviet Union successfully put Sputnik into orbit. Launched by an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), a satellite could be replaced by a nuclear weapon. Bombers took hours before they reached their targets; an ICBM-delivered weapon could strike within 30 minutes, essentially negating evacuation as an option. Fallout protection of any type seemed advantageous but Eisenhower and Congress decided it was too expensive. Federal civil defense officials instead encouraged Americans to build private fallout shelters – but little more.

5. 1961 – National Fallout Shelter Survey

Cover of the booklet, Fallout Protection: What to Know and Do About Nuclear Attack (left), and a picture of a National Fallout Shelter Survey sign (right).

Returning from tense meetings with Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, in July 1961 President John F. Kennedy addressed the nation to request funding from Congress for a fallout shelter program and promised to provide citizens with information about how to protect themselves in case of nuclear attack. Congress funded the National Fallout Shelter Survey to survey, mark, and stock existing buildings so they could serve as public fallout shelters. Begun with great optimism, the program intended to identify and stock 50 million shelter spaces by December 1962.

At the same time, the Kennedy administration published Fallout Protection, an informational booklet about fallout and shelters that was part of an effort to provide every citizen with information. Its reception was lukewarm. Questions arose over whether a fallout shelter network would even work or whether it would only scare the population by making nuclear war more imaginable. After Kennedy’s initial funding request of 1961, Congress never again appropriated sufficient funding to fully support the shelter survey effort.

6. 1962-63 – Cuban Crisis and Limited Test Ban Treaty

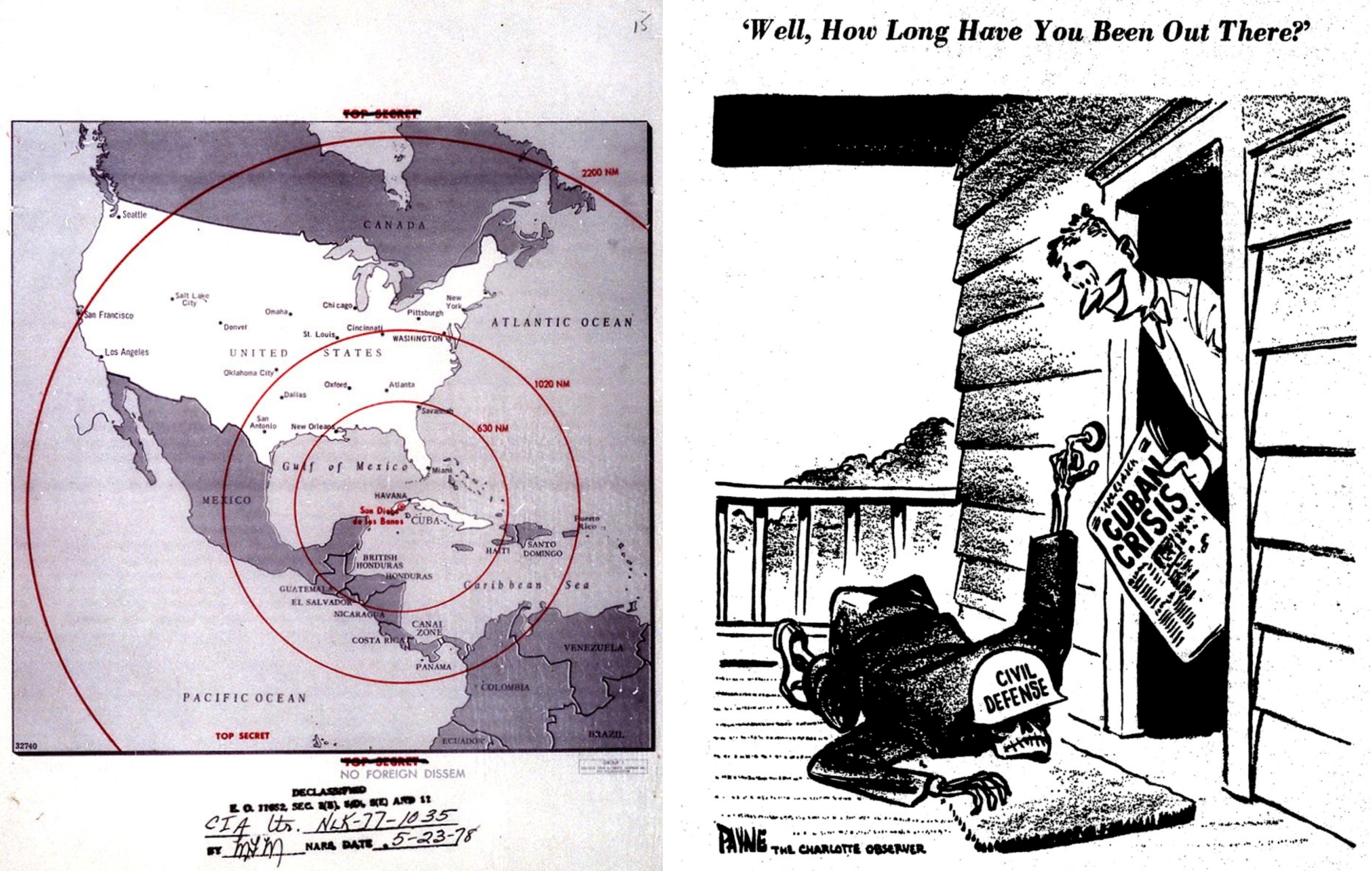

Map illustrating missile ranges during the Cuban Missile Crisis (left), and a political cartoon from the Charlotte Observer depicting the neglect of civil defense and reading "Well, how long have you been out there?" (right).

Over thirteen days in October 1962, the United States and the Soviet Union came to the brink of nuclear war over the construction of medium and intermediate range ballistic missiles on Cuba. Despite the earlier optimism of the National Fallout Shelter Survey, most designated shelters still lacked supplies. Ominously, Kennedy was informed that should Soviet missiles launch, little to no fallout protection existed in rural areas of the country and evacuation would most likely only induce panic.

Only luck and diplomacy prevented nuclear Armageddon. Nonetheless, civil defense officials lowered protection standards for shelters to increase the number of possible spaces and expedited the stocking and marking of shelters nationwide.

Despite the shelter survey moving into high gear for the remainder of 1962 and throughout 1963, the Cuban Missile Crisis cooled public attitudes for civil defense and fallout shelters. In August 1963, representatives of the United States, Soviet Union, and United Kingdom signed the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty banning the testing of nuclear weapons or devices in the atmosphere, underwater, in outer space, or any environment that risked the spread of fallout to areas outside the border of the testing state. The threat of fallout and nuclear war—and the need for shelters and funding for a robust civil defense effort—both faded from public discussion.

7. 1972 – Goodbye, Civil Defense

Cover of a 1972 informational booklet, Introduction to Civil Preparedness (left), and emergency preparedness in action during tornado recovery efforts in Xenia, Ohio in 1974 (right).

In early 1964, President Lyndon Johnson and Congress balked at an expansion of the nation’s public fallout shelter system and reassigned the Office of Civil Defense from the Secretary of Defense to the Office of the Secretary of the Army. Throughout the remainder of the decade, annual federal civil defense budgets steadily declined. Rather than invest in nuclear preparedness measures or shelters, state and local governments increasingly turned to civil defense resources to respond to peacetime natural disasters and localized emergencies.

This shift, from wartime civil defense to peacetime civil preparedness, became codified during the first administration of President Richard Nixon. In May 1972, the Office of Civil Defense was disestablished and its functions transferred to the Defense Civil Preparedness Agency. The name of the new agency reflected its priority.

The mid-1970s represented the nadir of civil defense readiness to combat nuclear attack with the National Fallout Shelter Survey reduced to a skeleton effort. Federal efforts instead opted to reemphasize public evacuation efforts, optimistically labeled “crisis relocation planning.” If nuclear attack appeared imminent, residents of high risk cities would evacuate to rural host areas using their personal vehicles.

8. 1983 – The Day After a Nuclear Freeze

DVD cover image of the 1983 film The Day After (left), and the Shelter Management Handbook (right).

By the early 1980s, public debate and protests over nuclear war, nuclear testing, and civil defense reemerged in the newly created Federal Emergency Management Agency, established in 1979. In 1981, President Ronald Reagan advocated for increasing and modernizing the nation’s nuclear arsenal and publicly announced plans to increase the nation’s civil defense program, in part to provide greater protection for the public but also deter Soviet actions. The plans included massive investments in “continuity of government” efforts to protect government leadership while continuing to rely on public evacuation efforts.

Beginning in 1980, the American Nuclear Freeze organization gained substantial public support advocating for a bilateral freeze on production, testing, and deployment of nuclear weapons. Suddenly in March 1983, Reagan announced his Strategic Defense Initiative intended to create a space-based missile shield to counter nuclear threats, a seemingly ideal civil defense solution to nuclear attack.

That same November, 100 million Americans watched a television movie, The Day After. Depicting the aftermath of a nuclear exchange on Midwestern Americans, the film unsettled and depressed public and policymakers alike. Civil defense once again fell out of discussion as nuclear disarmament efforts made headway between the United States and Soviet Union.

9. 1991 – End of the Cold War

Soviet era poster on radioactive contamination and civil defense patches (left), and the interior of an abandoned Soviet bomb bunker (right).

On December 25, 1991, the Cold War abruptly ended in Moscow when the Soviet Union was dissolved. Earlier that year, the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START I) took effect and the United States and Soviets each began to dismantle 6,000 strategic nuclear weapons. In 1993, the United States and Russian Federation signed START II to eliminate from 3,000 to 3,500 nuclear weapons apiece and eliminate the most capable ICBMs.

With the threat of nuclear annihilation apparently over, civil defense all but vanished as emergency management response to natural disasters became the paramount focus of federal, state, and local governments. Federal funding and resources for nuclear and radiological protection training was curtailed. Fallout shelters and Bert the Turtle became topics of scholars and museum displays, curiosities from a different age.

10. 2002 – Homeland Security Says “Duct Tape and Cover!”

The Homeland Security Advisory System (left), and satirical image "Duct Tape and Cover" (right).

The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 reignited a massive effort to protect the country from future threats. On November 25, 2002, legislation established the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Tasked to prepare for, prevent, and respond to domestic emergencies, primarily terrorist attacks, 22 previously existing federal agencies merged to form the new department, including the successor to civil defense, the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

DHS appeared to have civil defense déjà vu in its first years of existence. In March 2002, the department unveiled a confusing Homeland Security Advisory System of color-coded terrorism threats with no objective criteria to describe each threat level.

In February 2003, Homeland Security officials recommended that citizens purchase duct tape and plastic sheeting to seal doorways and windows in the event of a chemical or biological attack. Critics aptly derided this as “duct tape and cover.” Bert the Turtle would be proud.

2018 – Let’s Face It

The recent developments in North Korea’s nuclear program coupled with policy discussions in Washington about investing in new nuclear weapons research raise new questions about public safety should nuclear bombs or missiles detonate on or above the United States. The issues of public versus private protection and Presidential directive versus Congressional support for civil defense remain unresolved.

Beyond the billions of dollars invested in a missile defense system of uncertain reliability, there is presently no public protection from radioactive fallout or nuclear attack in the United States.

[All images from author's personal collection unless otherwise noted]