Information about our lives is being collected constantly. And yet neither businesses nor the federal government seem able or interested in increasing protections for our privacy. This month historian Lawrence Cappello reviews the history of data collection, the debates they have generated, and the mistakes that privacy advocates have made trying to protect our personal information.

This is the part where I’m supposed to scare you. The part where, like other privacy scholars, I inform or at least remind you, with a sweep of bleak Orwellian imagery, that the average American living in the Internet Age hands over dozens of snippets of very personal information to a host of strangers daily. Sometimes they do so knowingly, but more oftentimes not.

That information is then recorded, reconfigured, and redistributed in ways that few people really understand. Did you know that Team USA instructed all its athletes not to bring their phones to the Winter Olympics in Beijing because the security risks were too severe? Did you know that Mark Zuckerberg keeps a plastic slide over his laptop webcam and that experts agree you should too? Did you know that the word privacy doesn’t appear once in our Constitution? All of this is true.

As I write this, the United States has the weakest data privacy protections of all the advanced democracies. It’s no secret that the standards of privacy experienced by our parents and grandparents when they were our age are rapidly disintegrating in the face of wondrous technological marvels. Figuring out how best to balance our technological golden age with the fundamental human desire for privacy is a question that will largely define the next generation.

So how did we get here? Why has our response to this challenge been so inadequate?

Our popular historical narrative says technology is to blame—that after mainframe computers burst onto the scene in the middle of the twentieth century they kept evolving, which made our lives easier and more efficient, and so Americans willingly traded a little privacy for a little convenience until we all woke up one morning and realized things had perhaps gone too far but by then it was too difficult to roll things back. We had become too dependent. Worse, we had become too complacent. And now our privacy is circling the drain.

But the real history of data privacy in America is considerably more interesting. Technology, of course, had a large role to play, but we should be wary of such deterministic thinking. The machines didn’t make us do anything.

Our nation’s inability to properly address the privacy problems associated with big data have as much to do with how people in power made certain decisions and privacy advocates made certain mistakes. We can learn from these decisions and mistakes moving forward, because it’s not like we didn’t see this coming.

As Congressman James Oliver eloquently put it in 1961 when asked about the growing popularity of computerized data collection: “it’s my impression that these machines may know too damn much.”

Personal Data for the Public Good

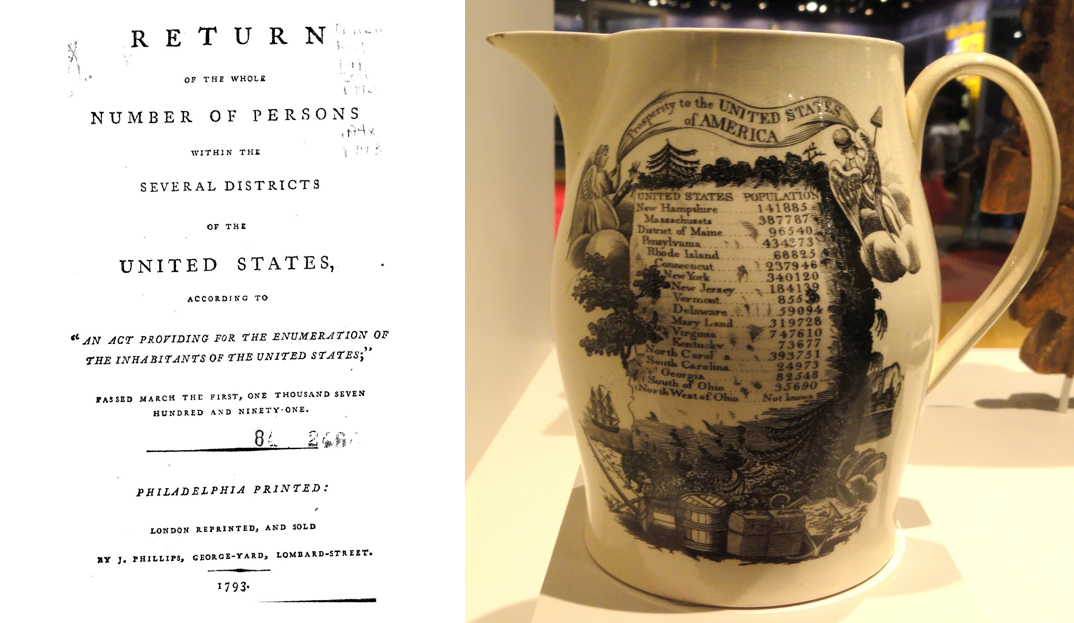

The origins of our modern debates about big data date back to the early days of the republic. When the framers wrote our Constitution, they made the United States the first nation in history to legally demand a regularly scheduled enumeration of citizens. Counting people wasn’t a new idea, of course. Nations have acquired, refined, and made use of data about those they govern for millennia.

The first census takers in 1790 were required to ask only six questions on behalf of their new nation, all of them purely demographic. Nevertheless, pockets of resistance quickly formed throughout the United States. Some refused to answer, some gave false names, others opposed on religious grounds. A census taker in rural Pennsylvania was killed. The final number came in just shy of four million inhabitants. Washington and Jefferson both expressed skepticism at that figure, suspecting that many people had “understated” to the census takers “the number of persons in their families” out of fears the census was really about tax collection.

Still, the framers were rightly convinced that collecting and recording certain facts about the country’s citizens could have a tremendous impact on the public good. Alexander Hamilton argued that the census ought to provide “an opportunity of obtaining the most useful information for those who should hereafter be called upon to legislate for their country,” and would “enable them to adapt the public measures to the particular circumstances of the community.”

When he was president, Thomas Jefferson advocated for a significant increase in the number of census questions to create “a more detailed view of the inhabitants of the United States under several different aspects.”

With few exceptions, every successive census has asked more questions than its predecessor.

This perceived connection between large-scale data collection and the public good found new champions during the Great Depression. President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal expanded the amount of information the federal government collected about its citizens exponentially. This was only natural. Before extending social welfare benefits to an individual a government agency will naturally have some questions about their situation.

In some instances, all a federal office required of applicants was a name, date of birth, and current address. But in most cases, to engage with the state for social welfare benefits also meant relating more personal details like financial information, criminal history, marital status, medical history, and level of educational attainment. By the late 1930s, with the introduction of Social Security, almost every taxpaying American had a government issued number that was exclusive to them.

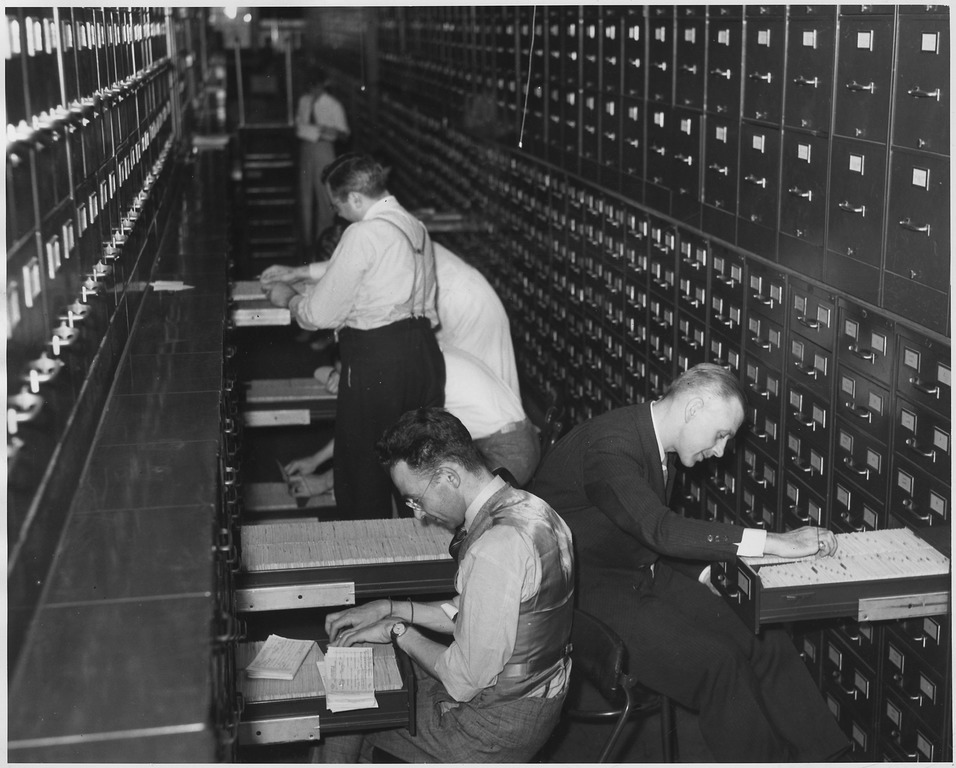

That meant record keeping. Records would need to be stored in a manner that was simultaneously secure and easily accessible. Thomas J. Watson’s company, the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), was eager to provide Uncle Sam some assistance.

IBM’s meteoric rise in the middle of the twentieth century was due in no small part to the American government’s increasing need for data storage and processing as it expanded the social safety net. As the New Deal was creating a slew of new federal agencies, the United States became one of the company’s best customers.

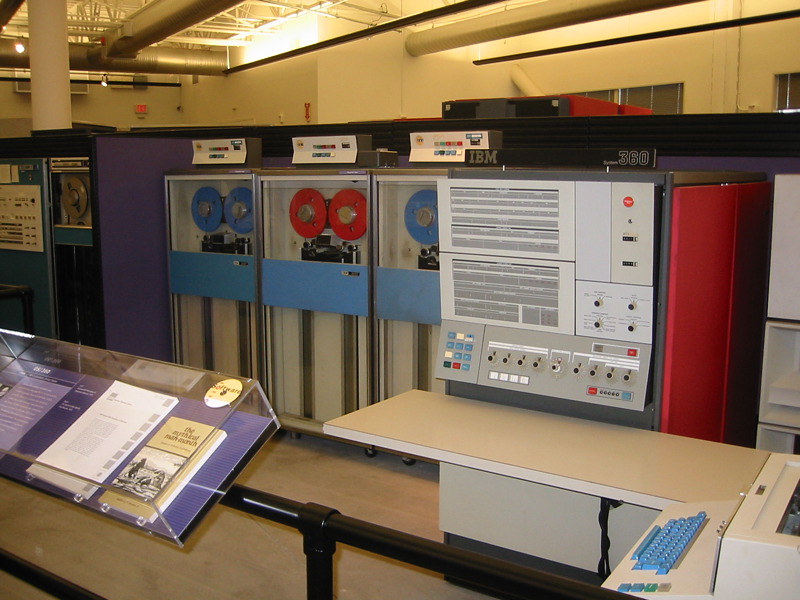

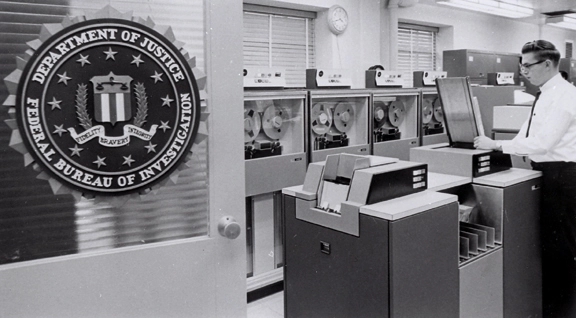

The Social Security Administration, in particular, kept almost all of its information on punch cards and by 1943 had acquired almost 100 million records. Punch cards gave way to magnetic tape in 1946 with the advent of mainframe processors—affectionately called “Big Iron.” Memory capacity swelled. Data processing reached speeds previously thought impossible.

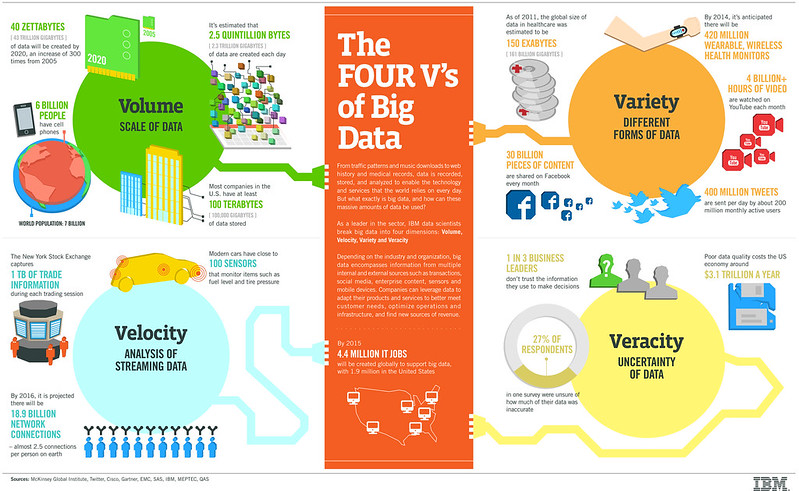

Big Iron’s historical significance isn’t so much about data storage as it is about the increased sharing and centralization of that data.

Prior to the widespread use of mainframe computers, federal offices like the Internal Revenue Service, Social Security, and the Department of Education and Welfare each maintained its own catalogue of records. Big Iron made it possible to streamline this data, making it much easier to access and share between the branches of government. After all, it’s much less expensive to share data than it is to recreate it.

By the 1960s, a new generation of social scientists started including all this new government data into their research as they sought to better understand the precise socioeconomic conditions facing millions of Americans. Again, well-intentioned individuals sought to harness big data as a tool to further the public good.

But in their zeal for social reform to help Americans, many of these academics began to complain that government recordkeeping wasn’t as efficient and accessible as it might be.

In 1965 they organized and came up with a solution: Congress should fund the creation of a National Data Center that would centralize all the information collected by all agencies of the federal government in one place for ease of access. The pitch was for one giant nucleus of government data with information about every American citizen.

A congressional subcommittee was formed to consider the proposal. Hearings began that same year.

Some advocates argued the proposal wasn’t really that revolutionary. The government already collected, organized, and published vast amounts of data in response to both state and public demands. Others argued that the digitization and centralization of government records would further the cause of knowledge while making social welfare more efficient, less expensive, and therefore more effective.

John Macy Jr., Chairman of the U.S. Civil Service Commission argued that to make proper decisions “will require the use of information across departmental boundaries,” which would then free his staff from mundane data related tasks and “liberate the manager to give his mind to greater scope of creativity.”

But these ideas did not go unopposed.

The first privacy advocates of the big data era testified in the Senate that the data center would mark the end of privacy and give rise to an Orwellian age of the “computerized man.”

Vance Packard, the celebrated author and journalist, leaned heavily on that metaphor, arguing “1984 is only 18 years away. My own hunch is that Big Brother, if he ever comes to these United States, may turn out not to be a greedy power seeker, but rather a relentless bureaucrat… and he, more than the simple power seeker, could lead us to that ultimate of horrors, a humanity in chains of plastic tape.”

The privacy advocates stressed that there was an inherent moral component to the idea that a person’s history, fragmented sloppily across digital tape, could never die; that the notion of an inescapable past was somehow un-American; and that it showed no respect for the full spectrum of the day-to-day human experience and would make us all prisoners of our past mistakes.

Privacy carried the day. The Senate rejected the proposal. But the victory proved a hollow one. For the rest of the decade federal agencies continued to collect and share data at an unprecedented rate. They also started sharing their files more openly with private companies.

From Public Good to Private Profit

By the early 1970s, corporate America was using data gleaned from government agencies for a variety of reasons, not the least of which was to make their direct marketing campaigns more sophisticated.

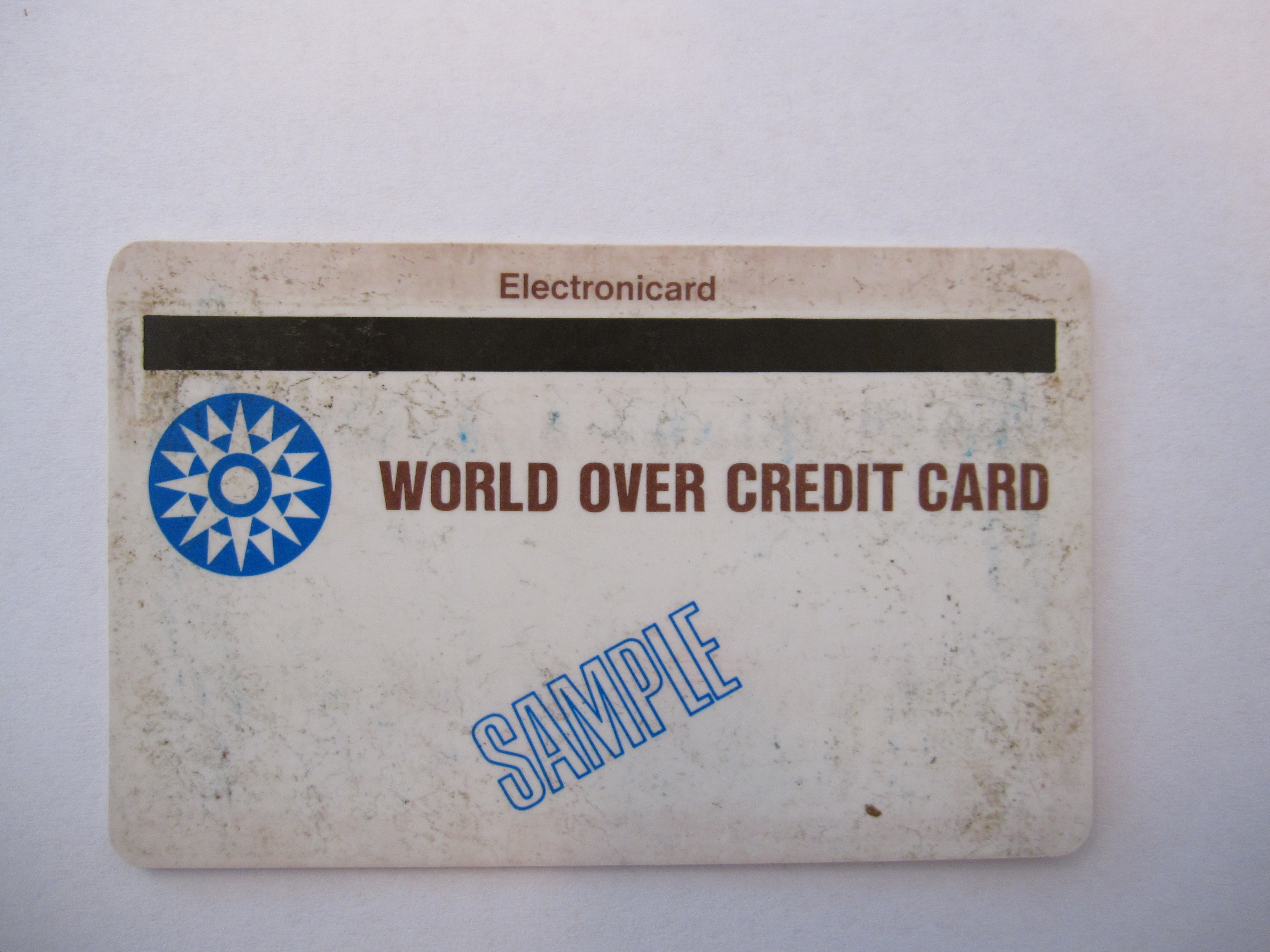

With the rise of the credit card industry, consumer debt in the United States had risen to over $51 billion—almost ten times what it had been at the end of World War II. And with so much on the line, credit bureaus began relying on computers to access and share information in the hopes of identifying potentially bad investments.

Unlike today where three main credit bureaus dominate, 1970s America was home to more than fifty bureaus that bought and exchanged consumer information with insurance companies, investigative firms, private companies, and the government, all with little oversight.

No regulations. No rules. No limits: It was the Wild West of data sharing. It’s here where the lines between public and private data started getting blurrier. Symbiotic relationships formed across multiple sectors.

Businesses wanted big data because big data made their organizations more efficient and profitable. Bank account information is of interest to credit card companies. Medical information is of interest to insurance companies. Tax returns are of interest to mortgage lenders. All information is of interest to advertising agencies.

But as this information became more and more democratized, more and more complaints arose of reporting errors bringing disastrous consequences for individual Americans.

Suddenly, big data was in the news, and not as a tool for the social good. Mike Wallace of CBS capitalized on the climate. In March 1969, the showman established a dummy corporation on live TV, printed up letterhead, rented a mailbox, and requested reports from twenty credit bureaus on people selected at random from the telephone book. Ten of them provided full reports without question.

The privacy crisis became unignorable. Journalists, scholars, and popular media suddenly began investigating the precise nature of federal recordkeeping and exactly how much information was being shared with (and among) the private sector.

What they uncovered was troubling: over a thousand databanks were sharing and storing information about the private lives of millions. Worse, oversight was disturbingly unclear. Every legal analyst agreed that existing law was wholly inadequate to protect privacy rights in the face of rapid technological change.

Congress had no choice but to respond to the growing discontent. In 1970, they passed the Fair Credit Reporting Act, the country’s first information privacy law.

Three years later, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) issued a scathing report expressing a number of privacy concerns, not the least of which was that every American now had a “standard universal identifier” that was allowing bureaucrats and corporate actors to more easily obtain and share their private information without their consent.

They were talking about Social Security numbers, which every American has. Social security numbers were originally conceived during the New Deal exclusively to meet the organizational needs of the Social Security Bureau. But as the federal government kept expanding in the decades that followed, it started using the number as an identifier for workers, taxpayers, students, servicemen, and pensioners.

The introduction of social security benefits was undoubtedly among the greatest accomplishments of twentieth century domestic policy. It has enabled tens of millions of Americans to live out their golden years free from the fear of poverty. But the inability of the federal government to restrict the use of social security numbers for purposes that had nothing to do with social security was undoubtedly among the worst catastrophes in the history of American privacy rights.

The HEW report, shockingly prescient, concluded with several legislative recommendations. Packaged as a “Code of Fair Information Practice,” it said that any law designed to regulate big data would need to ensure certain basic safeguards.

There must be no secret data-based record keeping systems. There must be a clear process through which individuals could access their own records and correct errors. There must be a means for individuals to prevent information obtained for one purpose being used for other reasons without consent. And there must be a requirement that any organization engaging in information collection take appropriate measures to prevent the misuse of the data they hold.

Taken together these recommendations, called “Fair Information Practice Principles” (tech professionals call them FIPPs) now serve as cornerstones for most global privacy laws.

Congress responded with the Privacy Act of 1974, passed in the wake of the Watergate scandal. It defined the rights of access to information held by federal agencies and placed restrictions on the collection, use, and disclosure of personal information. No small feat.

The law was also a tremendous failure. It provided only minimal protections for information privacy and was rife with loopholes and ambiguous language. It also completely excluded private companies from its provisions.

Why exclude private companies? The answer was simple: data privacy laws would inhibit profits.

Originally intended to apply to both private and public data collection, the Privacy Act was eviscerated by corporations and special interest groups who argued that privacy controls on their consumer databases would harm their profits and destroy American businesses.

Interests like the American Life Insurance Association, representing 367 companies accounting for over 90 percent of the legal reserve life insurance in the country, claimed the effects would be “extremely burdensome … not only unfair, but unworkable.”

A group of 260 literary publishers argued that unless direct mailing companies and mail order book clubs were explicitly exempted, “the impact on the publishing industry could be devastating.” The private sector would be regulated by individual states, not the federal government.

And so largely because privacy and profits did not mix, American lawmakers squandered a major opportunity to establish a legal framework that could rein in the privacy abuses of big data before the internet age bought those abuses to new heights.

Bigger Data in the Era of “Small Government”

In the 1980s, companies that profited from big data found a powerful ally in President Ronald Reagan. The “Great Communicator” loudly encouraged the expanded use of government data collection and processing not, like some of his predecessors, to enhance the distribution of social welfare benefits, but as a powerful tool through which the waste and inefficiency of “big government” could be eliminated.

Under Reagan, the government launched a series of welfare fraud investigations using Big Iron to audit records for irregularities. This practice of computer matching, or “data mining,” took different forms but generally involved cross-referencing millions of names and social security numbers from one agency with those of another to identify inconsistencies that might suggest fraud.

Hundreds were prosecuted as a result; agencies estimated that they had saved taxpayers millions of dollars. Make no mistake, many of those caught were actively cheating the social welfare system and committing federal crimes.

Many also weren’t. The process lacked proper safeguards and soon encumbered thousands of Americans who were not swindling their government. Cases of mistaken identity were common and led to wrongful arrests, unwarranted employment terminations, obliterated credit scores, and the mistaken refusal of medical benefits to eligible citizens.

By the time the actual 1984 rolled around, claims of Fourth Amendment violations were growing more frequent, as were charges that individuals had almost no dominion over their information and couldn’t challenge its accuracy or limit its dissemination. These arguments almost always incorporated Orwellian imagery—asserting, as one writer put it, that the “technology of privacy invasion” had moved “from the realm of science fiction into the world of public policy.”

By then it was too late.

The regulation of data mining in the 1980s effectively legitimized it. Those with an eye for irony were quick to note that a vast expansion of federal information processing was being conducted under the banner of “small government.” The United States, whether it wanted to admit it or not, now had a de facto national database, the thing Congress had rejected twenty years earlier.

Over time, privacy advocates were forced to settle for “sectoral” or patchwork policy remedies that regulated different industries such as banking or libraries or insurance companies in different ways, often on a state-by-state basis, instead of the immensely more effective “omnibus” remedies adopted by other advanced democracies that applied a uniform set of rules about particular kinds of information to every industry.

American lawmakers had squandered their chance to provide citizens with meaningful control over the storage and use of their personal information. This ultimately left the nation, at the dawn of the Internet Age, woefully ill-equipped to handle the tidal wave of new data privacy problems that would come next.

Where We Go from Here

There are, fortunately, some lessons we can take from this story moving forward.

The first, obviously, is that there is a well-documented historical tension between privacy rights and the profit motive. Opposition to meaningful data privacy legislation has generally come from those who stand to lose money by protecting consumer privacy. In the twentieth century, privacy and profits were at cross purposes, and profits won out.

This dynamic is now changing. Here in the twenty-first century, privacy is starting to become a commodity. Modern consumers want the latest tech, but they’re also concerned about how their data is being used and companies have been eager to profit from those concerns.

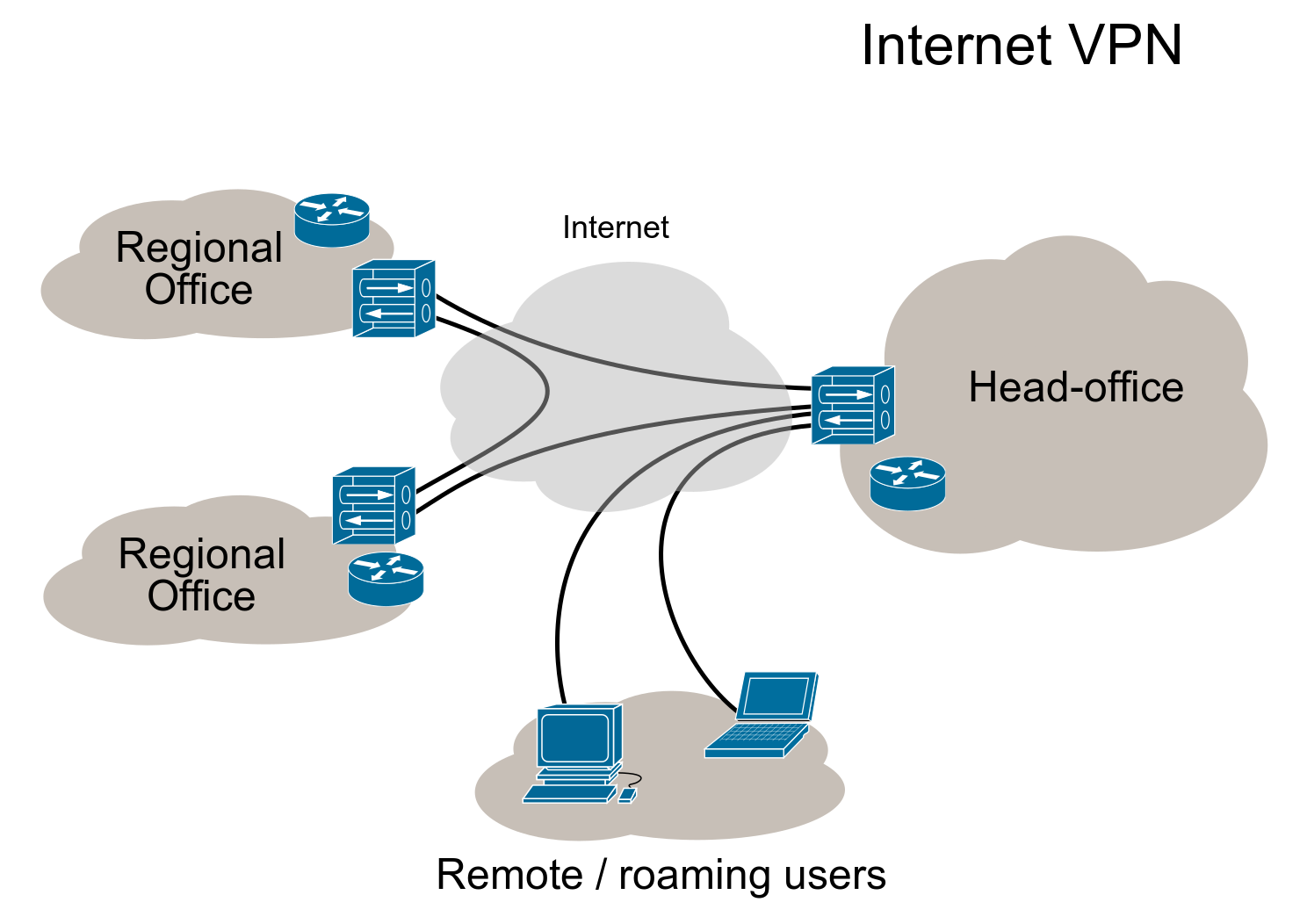

The popularity and market share of virtual private networks (VPNs) has skyrocketed over the last five years. Cybersecurity is now a multibillion-dollar sector. Even Apple has started aggressively branding itself to consumers as a privacy friendly company, and they’re not the only ones.

Don’t misunderstand. Modern companies still make trillions sharing data in ways we find patently objectionable. The rise of what Shoshana Zoboff called “surveillance capitalism” is a very real thing, and I’m not saying American tech firms are suddenly champions of privacy who won’t still misuse customer data if there’s money to be made from it.

But, for the first time in the history of big data, privacy finally has something resembling a counterweight when it comes to profits.

Businesses have started to realize that caring about privacy can create marketing opportunities and give them a unique advantage over their competitors. It’s one of those rare moments for executives where the profitable thing is also the right thing to do.

What makes this economic approach to privacy so attractive is that it doesn’t rely on our better angels or popular will. It relies on self-interest and greed. If companies in a capitalist society see that they can get rich protecting privacy, or that they can go broke if they don’t, change is much more likely. We can, in effect, buy our way to a more private society. We’re not there yet, but it’s something to keep an eye on.

As long as there are vast sums of money to be made selling services to those who wish to keep their communications and data free from prying eyes (or vast sums of money to be lost by not protecting that information) privacy will always have a heartbeat in the digital age. It is very much in America’s interest to keep privacy profitable.

The second lesson has to do with where the modern privacy battlefields are located.

Information generally moves across three stages. First, it’s collected, which presents its own privacy problems. Then the people collecting it process it. Then they re-disseminate (or share) it. Data professionals call this journey information “flows.”

The collection stage is a privacy battle we lost in the twentieth century. Which isn’t to say that we still can’t actively try to prevent our sensitive information from being collected by strangers, but in the Internet Age any attempt to meaningfully stem the tide of data collection is largely a fool’s errand. This is not a popular view among some privacy advocates, but it’s the truth.

Our societies and cultures and economies are now thoroughly dependent upon digital technology, and it’s not like people are going to suddenly throw away their phones and laptops and credit cards and go back to simpler times.

The real battle over data privacy today is about protecting personal information after it has been collected. Limits on access, limits on sharing, full transparency from those who hold data, and the ability to have data deleted after a set period of time—commonly known as the “right to be forgotten”—these are the modern privacy battles that deserve the lion’s share of our energy.

The only way to properly protect data privacy rights is through comprehensive “omnibus” legislation that resembles Europe’s General Data Privacy Regulations (GDPR), and by officially recognizing data privacy as a fundamental human right.

Finally, those inclined to play the political blame game for our present privacy predicament may find themselves disappointed. Both sides are partially to blame for where we are now.

It was American liberals in the 1930s and the 1960s, with their emphasis on social welfare, that played the greatest role in the expansion of data collection. It was American conservatives, in the 1970s and the 1980s, that played the greatest role in the increased processing and sharing of that data in the name of efficiency, profits, and “small government.”

Above all, the greatest mistake privacy advocates have made has been to frame data privacy as an individual right while ignoring its larger societal value. This crucial error often allowed those forces that pushed against privacy to argue for the “greater good,” while those defending it frequently spoke of individual harms—a somewhat weaker position.

People who care about the right to privacy need to understand that when they only defend privacy as an individual right they are dooming their cause to failure. The desire for privacy is a fundamental aspect of the human condition. It is absolutely an individual right. But if we really want to defend the right to privacy, the strongest arguments are the ones that use the language of individual rights and societal rights as a kind of one-two-punch.

Imbuing data privacy with the language of human rights law would be an excellent place to start. Either way, if American privacy advocates can take any wisdom from the mistakes of their forbears it is that they need to think bigger.

None of Your Damn Business: Privacy in the United States from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age, by Lawrence Cappello

1984, by George Orwell

Understanding Privacy, by Daniel J. Solove

Privacy and Freedom, by Alan F. Westin

The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, by Shoshana Zuboff