In April 1896, participants from 14 countries converged on Athens to compete in a festival that was simultaneously ancient and modern.

Billed as the first Olympic Games to be held since 393 CE and symbolically starting on Greece’s Independence Day (6 April), its Opening Ceremony filled the refurbished Panathenaic stadium to its 50,000 capacity, with similar numbers of spectators thronging the adjacent streets and surrounding hillsides.

Over the next nine days, the stadium, the existing Zappeion Building, and a small number of purpose-built facilities (a velodrome, shooting gallery, and seating for the swimming competitions) saw the staging of 45 events ranging from track and field athletics to cycling, weightlifting, and tennis.

Beyond the stadium, the city of Athens enthusiastically embraced the Games. Municipally sponsored illuminations, torchlight processions, pyrotechnics, and a cultural program of theatre and concerts provided after-hours entertainments for visitors.

It was a distinctive marriage between a sports event and its host city that was further symbolised by the way in which the marathon, run here for the first time, snaked its way through the city’s streets.

Cover of the official report of the 1896 Athens Summer Olympics, often listed as the poster of the Games. The distant stadium blends in with the imagery of Antiquity (left). The Opening Ceremony of the 1896 Olympic Games, held in the Panathenaic Stadium, Athens (right).

The idea of re-establishing the Olympic Games was not new.

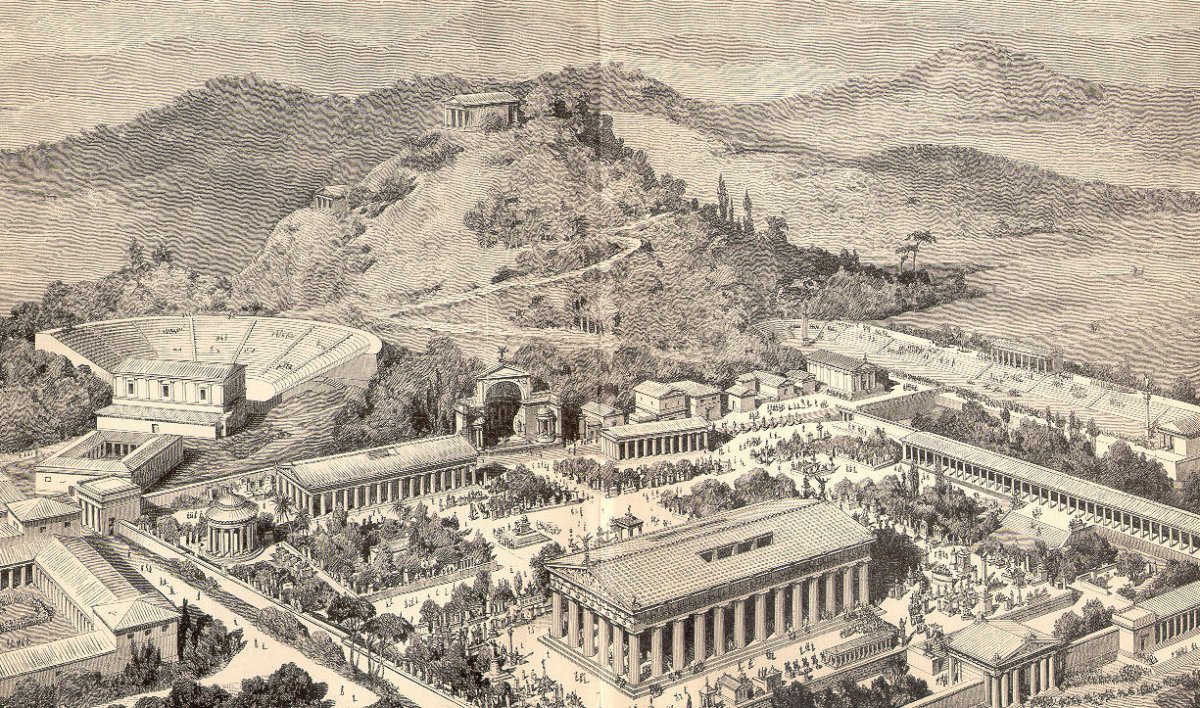

Knowledge about the Olympics and its significance for ancient Greek society had never fully faded from European consciousness. Indeed, late-eighteenth century archaeological excavations revealing the Games’ original site at Olympia on Greece’s west coast only strengthened interest. As more remains came to light, historians imaginatively reconstructed the events that had taken place there.

During the first half of the nineteenth century, separate initiatives occurred that consciously sought to build on those conceptual foundations, endeavouring to revive the Olympics as a premier celebration of sporting excellence.

Often motivated by a mix of nationalism and pedagogy, events appropriating the word “Olympics” included the Scandinavian Olympic Games of 1834 and 1836 (held at Ramlösa, Sweden), a Montreal Olympics in 1844, and the ongoing Wenlock Olympian Games founded at Much Wenlock (England) in 1850.

For their part, groups within Greece also sought to restore the Olympics as an affirmation of re-emerging nationhood after the country achieved political independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1830. Three such festivals were staged in Athens in 1859, 1870 and 1875.

The site of the stadium at Olympia, the permanent site of the classical Olympic Games.

None of these festivals, however, had direct connection with the 1896 Games sponsored by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) under the leadership of Baron Pierre de Coubertin.

Coubertin was an educational reformer who believed sport could be a vehicle serving both nationalist and internationalist goals, combining opportunities for national regeneration, and a meeting place for the nations of the world. He had launched the idea of restoring Olympic Games at Congresses held in Paris in 1892 and 1894, the second of which had produced an overall schema as to what the Games might look like.

In essence, the revived Olympics would mimic the ancient Games’ four-yearly cycle (known as Olympiads) but, like the World’s Fairs with which they would have much in common, they would be ambulatory rather than based at a permanent site.

The Olympics would offer modern rather than classical sports, would include a range of newly minted ceremonies and festivities designed to provide some continuity with the past, and would be governed by an agreed code of “fundamental principles, rules and by-laws,” known as the Olympic Charter. Finally, the Congress founded the IOC to control the Olympic movement and to select the host cities, although local Organizing Committees would plan and obtain the finances for the Games.

A memorial statue to Pierre de Coubertin outside the IOC’s Olympic Museum in Lausanne (Switzerland). The somewhat hagiographic treatment of its subject includes an everlasting flame. Image courtesy of the authors.

The question then is why the festival reintroduced at Athens 1896 has proven so enduring compared with other initiatives, which are now reduced—not always fairly—to footnotes in the historiography of the modern Olympics. The answer is essentially twofold, deriving partly from the success of the event itself and partly from the underlying model that it introduced.

With regard to the former, Athens 1896 demonstrated the IOC’s ability to latch on to a credible historical narrative from which to develop the Games. In Coubertin’s original vision, the modern Games recreated the panegyris of the classical festival: a festive assembly in which the entire people came together to participate in religious rites, sporting competitions, and artistic performance.

In practice, only a portion of this vision ever came to fruition. For example, attempts to accompany the sporting events with equivalent artistic competitions in which medals were awarded never fully functioned before eventually being abandoned in 1948.

Nevertheless, the ethos of a spectacular, culturally rooted, multisport festival dignified by non-denominational ritual and ceremonies remained, forming a consistent and flexible basis even as an ever-expanding slate of new sports and events were added throughout the years.

Another key to the Olympics’ enduring status that was first established in Athens is the relationships between the festivals and their host cities. For their part, the IOC and the Olympic movement have never had facilities or sufficient resources to stage the Games. They can achieve their goals only if their host cities are willing to shoulder the financial burden.

Tower Bridge lit up with the Olympic Rings to celebrate the London 2012 Summer Olympics.

At the outset when the Games were relatively small, this did not prove much of a barrier. At the 1896 Athens Olympic Games, most of the sporting action took place in existing or refurbished arenas, with officials and sporting participants housed locally in hotels. The city was happy to meet the costs in return for hosting an event that had resonances with the glories of the state’s classical past as well as gaining some tourist revenue for the city’s exchequer.

Over time, however, the costs involved and the reciprocal benefits expected changed considerably, particularly due to the Games’ increasing size and complexity. Given that the cities were effectively the paymasters, a larger commitment of resources tended to require a commensurate increase in benefits beyond the transitory gains from tourist revenues and from staging a globally prestigious event.

Agendas became linked, among other things, to urban regeneration, large-scale housing projects, national brand-formation, and infrastructural improvement. Taken to its extreme, as at Barcelona in 1992, the host city would devote the overwhelming bulk of investment (83%) to recreating the urban fabric rather than on staging the Games.

Nevertheless, the relationship between host city and the Olympic movement remained dynamic, with the IOC able to attach new goals for, say, sustainability and legacy in the last 30 years.

Urban renewal in Barcelona as a direct result of the 1992 Olympics. The two tower blocks shown, now converted to hotel, office, and residential space, were once the Olympic Village. Image courtesy of the authors.

The IOC’s ability to exert pressure ultimately depends on having an adequate supply of potential host cities willing to compete to stage the Olympics. In recent years, this supply has dwindled, with fewer cities submitting bids to serve as hosts for future events.

Nevertheless, the Games’ longevity — continuing to the present day and beyond with its regular cycles only broken by the two World Wars and the COVID-19 pandemic — indicates that the underlying model has effectively absorbed change and adapted to dramatically varying political and economic circumstances.

In a very real sense, the formula that Coubertin and the IOC successfully established at Athens 1896 remains resilient.