The onset of COVID-19 has been shocking—in terms of global spread and relatively high lethality—but it is hardly the first pandemic to have such a sudden and alarming onset. When cholera first arrived in Europe in 1829, the horrific symptoms it caused were so alarming and overwhelming that it was described as the “nineteenth century plague.”

Like plague, cholera followed trade routes out of its reservoir in the Ganges River delta in India into Central Asia and from there into Russia and westward across Europe. By 1832, cholera had spread across all of Europe and, by 1833, the disease crossed the Atlantic to both North and South America.

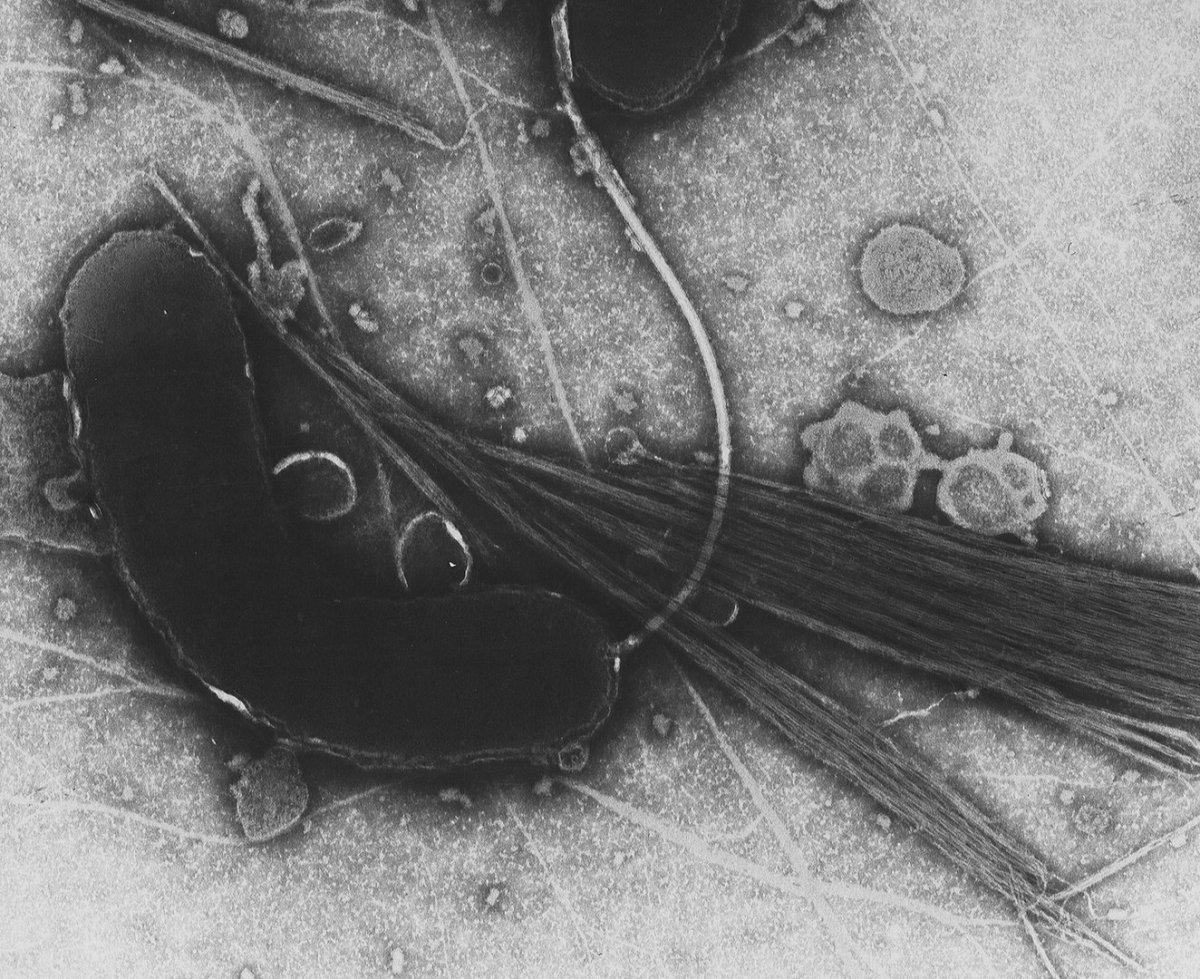

Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium that causes cholera.

The bacterial infection, caused by Vibrio cholerae, caused patients’ bodies to waste away in a matter of hours due to sudden dehydration and severe diarrhea. Although the morbidity rate (the prevalence of a disease within a given population) was often low, mortality rates (fatalities among infected patients) reached as high as 50%, which further contributed to the shocking nature of the emerging disease.

In the last two hundred years, there have been seven global cholera pandemics (in 1817-1824, 1829-1837, 1846-1860, 1863-1875, 1881-1896, 1899-1923, and 1961-1975) and cholera remains a threat in much of the world.

The seventh and most recent pandemic (of the “El Tor” strain of cholera) occurred primarily in southeast Asia, the Pacific and beginning in 1970 spread across Africa. More recently still, localized epidemics broke out in parts of South America in 1991-1994 and in Yemen since 2016.

As of 2019, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), cholera still infects between 1.3 and 4 million people and is responsible for between 21,000 and 143,000 deaths annually worldwide, but especially in the global South where access to rapid rehydration technologies, antibiotics, and an oral cholera vaccine developed in 2015 is limited.

Vaccination team member giving a cholera vaccine in Cerca Carvajal, 2013.

The history of the cholera is critical to understanding modern public health. The impact of the disease in Europe shaped our understanding of how infectious diseases spread and formed the basis of modern epidemiological investigations. The cholera pandemics also contributed to technological and medical innovations in public health.

The arrival of the cholera pandemics in Europe reinvigorated a centuries-long debate about the cause of infectious diseases. The “contagionist” school of thought maintained that disease passed directly from person to person, though members of this school could not determine the specific mechanism of transmission.

By contrast, the “miasmatists” (sometimes called “anti-contagionists”) posited that environmental hazards like “bad air” (mal aria in Italian), resulting from the build-up of waste, exuded from ineffective sewers and caused illness and disease.

A depiction of cholera spreading through a black cloud of bad air, 1831.

Both theories had an element of truth in them, but neither fully explained the process by which diseases originated and spread. Each, however, influenced how different nations responded to the pandemic.

For example, in Imperial Russia during the second pandemic, the Tsar’s regime adopted a contagionist response to cholera. Strict quarantine and isolation of cholera patients were imposed by a strong regulatory state. This response was met with strong criticism from Western European states—both because it was deemed anti-liberal to establish a medical-police state and because the Russian response was largely ineffective in stemming the tide of cholera.

In Great Britain and France, by contrast, many doctors were inclined towards a miasmatic explanation of the pandemics and focused public health efforts on cleansing the “bad air” from their cities. Others, like the French medical statistician René Villermé, considered the spread of cholera to be a function of urban poverty and the cure for cholera was to improve the poor’s living conditions.

In Great Britain, Poor Law Commissioner Edwin Chadwick, from the miasma school, began to preach the “gospel of sanitation” beginning in the 1830s in response to the ebb and flow of cholera. Chadwick believed that “all smell is disease” and smell came from putrefying, rotting organic material that was not properly drained away from human residences. In this way, he maintained a classically anti-contagionist (miasmatic) perception of disease.

Sanitary Map of Leeds from Chadwick's 1842 report.

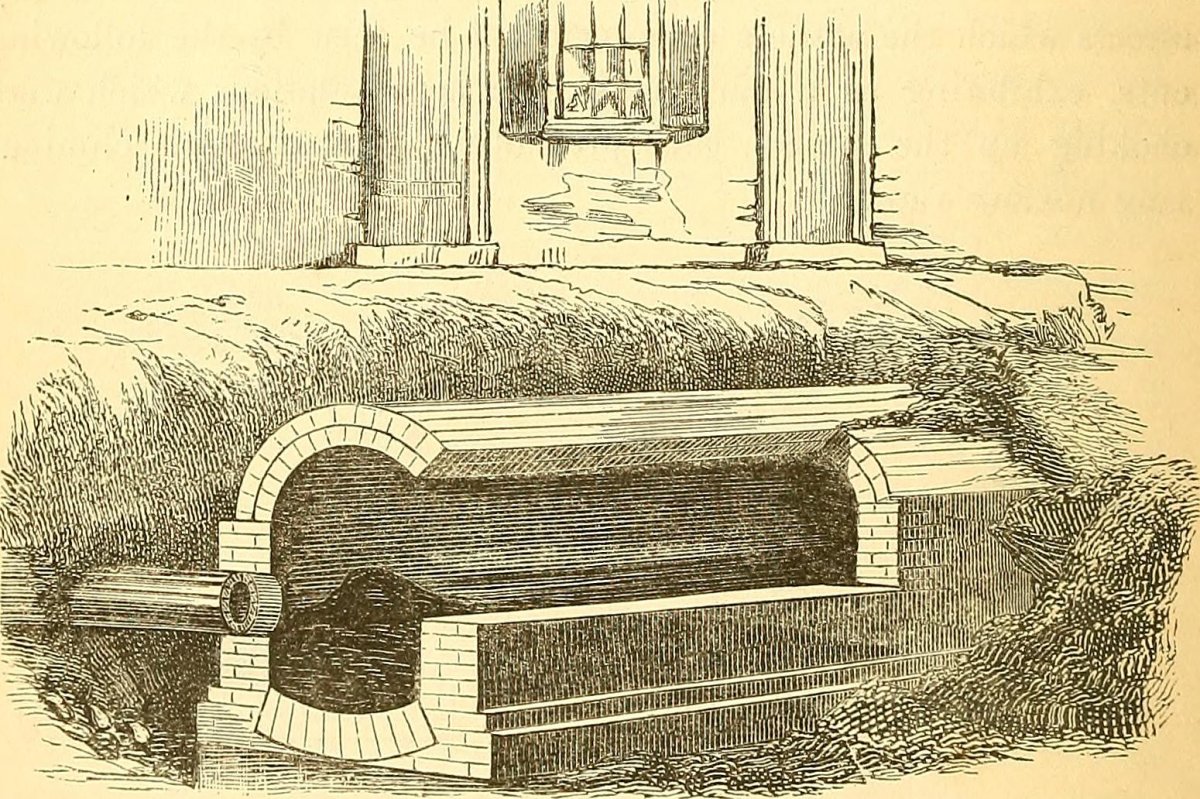

In his 1842 Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, Chadwick proposed his “sanitary ideal”: the state should create a central board for the oversight of public health that would direct local public health administration in the construction and maintenance of proper drainage and water supply systems in order properly to remove waste and improve air quality.

Chadwick’s sanitary ideal proved extremely popular among political and social reformers as an efficient mitigation of both disease and the expensive poor relief it necessitated.

The problem with Chadwick’s great technical fix, of course, was its underlying miasmatic assumption: that the buildup of filth polluted the air and then caused the disease and that washing away filth would rid London of cholera. During the third pandemic (1846-1860), the flaw in this assumption was revealed.

Observing adjacent neighborhoods of London, which should have been exposed equally to the same “miasma” but suffered vastly unequal numbers of cases of cholera, local doctor John Snow determined that in the Soho neighborhood residents who became ill all received their water from the same water pump: the Broad Street pump.

Removing the handle of the infected water pump resulted in a sudden drop in cases of cholera. In this important epidemiological investigation, Snow discovered a vital clue to controlling cholera: that it was a waterborne disease. However, it would take another decade (and another pandemic visitation) for this discovery to be broadly accepted.

Nevertheless, in the case of the Broad Street pump we see the historical roots of modern epidemiology, which is now a vital tool in following the path of a pandemic. At the same time, Snow’s discovery also invited further research into what it was in the water supplies that was causing cholera.

The answer of course was filth, especially human excrement, which carried the deadly Vibrio. By isolating cultures of the Vibrio (which was first observed under a microscope by the Italian anatomist Filippo Pacini in 1854) from cholera patients in Egypt and India in 1883-1884, German physician Robert Koch was able to connect cholera cases to their particular bacterial cause during the fifth pandemic.

Yet, even before Koch made this important discovery, cholera had already played a central role in broadening public health practices and institutions.

One point had become especially clear: sanitation was key to creating a healthier society. Creating a “sanitary ideal” required input from doctors, engineers (like Joseph Bazalgette who was tasked with redesigning the London sewer system in 1860s), medical statisticians, and state and local policymakers.

By its very nature, public health is a meeting point of all these different fields. And we can trace the institutionalization of public health to the European response to the series of cholera pandemics in the 19th century.

Alongside Koch’s discovery of the Vibrio cholerae bacteria and the gradual, ensuing adoption of the “germ theory” of disease over the last decades of the 19th century—which would end the contagionist vs. miasmatic explanation of disease etiology entirely—the cholera pandemics were essential, if devastating, moments in the origins of both modern public health and biomedicine.