Before voters in the United Kingdom opted to leave the European Union in 2016, the country observers felt most likely to do so was Greece. Reeling from the global financial meltdown that began in 2007 and then from the economic austerity measures imposed on it by Europe, many inside and outside Greece thought the best way forward would be to break from the EU. That crisis, however, was only the latest in a series. As historian Christopher Kinley explains, Greece has been plagued by a long history of debt crises that have hampered its growth and prosperity.

On a hot summer day in late June 2015, I stood in a long queue that wrapped around Athens’s busy Stadiou Street hoping to withdraw some euros from an ATM. After what felt like an eternity under the blazing sun, I was just two people away from the machine when I heard some Greek expletives and saw a commotion in front of me. The ATM ran out of money. I spent the next several hours scouring the city, but every bank was closed and every ATM was empty.

What felt like a scene from some apocalyptic movie was the result of Greece’s ongoing debt crisis. The day I had embarked on my search for an ATM, Greece defaulted on its payment to the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The result: in order to prevent the collapse of the banking system, the Greek government ordered banks to close their doors and limited the amount of accessible cash to just 40 euros a day per individual. For tourists, luckily, this monetary restriction did not apply. However, finding an ATM with cash proved a challenge.

Flash-forward to June 2018 and the announcement of a debt resolution, with some headlines going as far as to proclaim the Greek debt crisis over. The current mood in Greece is mixed. While some seem to agree that a new debt resolution will free Greece from its economic woes and prevent a fall over the cliff, others perceive any resolution offered as further kicking the can down the road and delaying an inevitable exit from the Eurozone (the countries in the European Union (EU) using the Euro as currency).

Whether or not debt relief will provide Greece with the opportunity to improve unemployment rates and prevent further economic collapse is yet to be seen, but what is not debatable is the long and complicated history that led Greece on a trajectory to the crisis plaguing the country today. By understanding the origins of the Greek debt crisis, we can better understand the interconnectedness of the global economy.

The Greek economic crisis made headlines in 2010. The world became aware that Greece’s economy was an ongoing casualty of the 2008 global recession and that the country would need to borrow billions to prevent governmental and economic collapse.

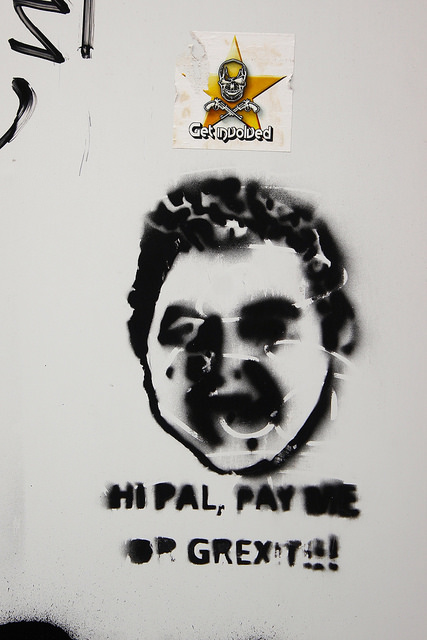

A 2015 projection on the German Embassy in London by the Global Justice Now organization.

This fragility in turn stoked fears that allowing Greece to fail would result in a domino effect and cause the demise of the Eurozone. Simultaneously, it created an anti-German movement within Greece itself as Angela Merkel became synonymous with plans to implement stifling austerity measures in Greece by cutting government pay and pensions while increasing taxes.

However, to designate Greece’s financial woes as a byproduct of the 2008 global economic crisis would be to misunderstand the country’s complex financial history. Economic troubles began with its creation and were compounded by 150 years of economic instability, debt, predatory lending by global powers, bankruptcies, political corruption, a faulty tax system, wars and refugee crises, and financial mistakes—problems that might be far from over.

Out From Underneath the Ottomans

Debt and default were with Greece from the very beginnings of its modern independent history.

In the popular imagination, Greece is an ancient place. We are taught that it was the birthplace of democracy and Western Civilization.

However, in terms of statehood, Greece is much younger than the United States and was born out of a revolution against the Ottoman Empire with the assistance of Britain, France, and Russia. For the 400 years it was under Ottoman rule, Greece remained a poorer territory of the empire and most of the population were farmers forced to pay heavy taxes to their local Ottoman proprietors.

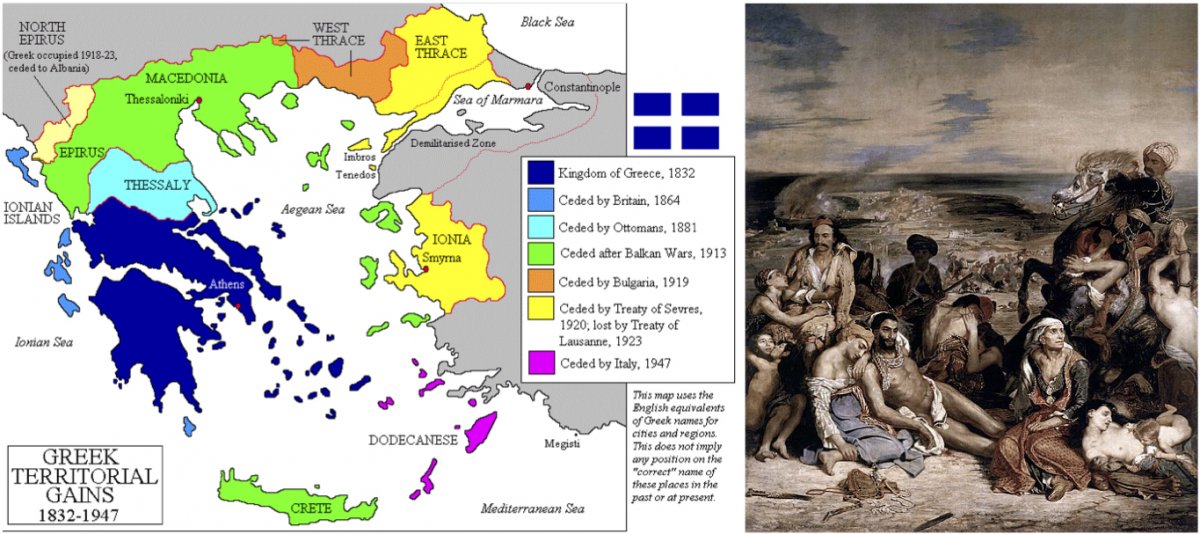

A map showing Greece’s territorial gains and losses from 1832 to 1947 (left). A painting depicting the slaughter of thousands of Greeks on the island of Chios by Ottoman troops in 1822 during the Greek War of Independence, an event that increased support for the Greek cause throughout Europe (right).

The only wealth to flow into Greece during this period was from prominent merchant families spread throughout Europe. Members of these families spearheaded the revolution for independence that erupted in 1821. The territory of Greece had no army and very little funds to finance military campaigns against the Ottomans.

Many Europeans and Americans, however, were sympathetic to the Greek cause. In light of these pro-Greek sympathies, representatives of Greece were able to procure two loans from Britain between 1824-1825 totaling 1.5 million pounds. Just two years later, and still in the middle of war, Greece was unable to make the interest payments on the British loans and the default resulted in bankruptcy.

A Bavarian prince, Otto became the first modern King of Greece in 1832.

Greece gained its independence in 1832 when Britain, France, and Russia created the country’s constitution, outlined its territory, and installed the Bavarian-born Otto as king. To allow the new country to integrate itself into international capital markets, escape bankruptcy, and modernize infrastructure (seaports, railways, sanitation, and government buildings) France loaned Greece 60 million francs.

With this new financing, Greece repaid the British loans and began to modernize the country through building infrastructure. But overspending led to a default on the French loan and resulted in a second bankruptcy in 1843, making two in just 20 years.

This second default resulted in public demonstrations and rapid political turnover as taxes reached a level above that experienced under the Ottomans. In 1862, Otto was deposed by the Greek people and Britain, France, and Russia crowned the Danish prince, William, George I of Greece.

King George spent the next decade improving Greece’s sociopolitical environment and putting the country back on track by chipping away at debts while digging out of bankruptcy. However, this period of fiscal progress was not without consequences. During the later period of George’s reign, the Greek state’s domestic and foreign policies were characterized by the costs of early industrialization, military spending, and territorial expansion that strained an already fragile economy.

To finance these policies, Greece again looked to Western Europe for more money, and from 1879 to 1893, Greece received six loans under usurious terms. These loans ranged from 135 million francs for military spending to 190 million francs for railway construction. In total, Greece borrowed more than 659 million francs in less than 15 years.

In what seems like a cyclic fashion, borrowing, overspending, and loan defaults once again led the country to its third bankruptcy in 1893. Unable to make interest payments, the Greek state was forced to accept the creation of the International Commission for Greek Debt Management.

The commission was allowed full control of Greece’s finances with the purpose of ensuring that all loans were repaid. The commission was to oversee the Greek tax system to guarantee the country was producing revenue at a maintainable level, as well as collecting the incomes from monopolies such as tobacco and salt. Part of the financial restructuring agreement was also a massive loan of 151 million francs. The commission remained in Athens until 1936, but Greece continued to suffer economic stresses during this period.

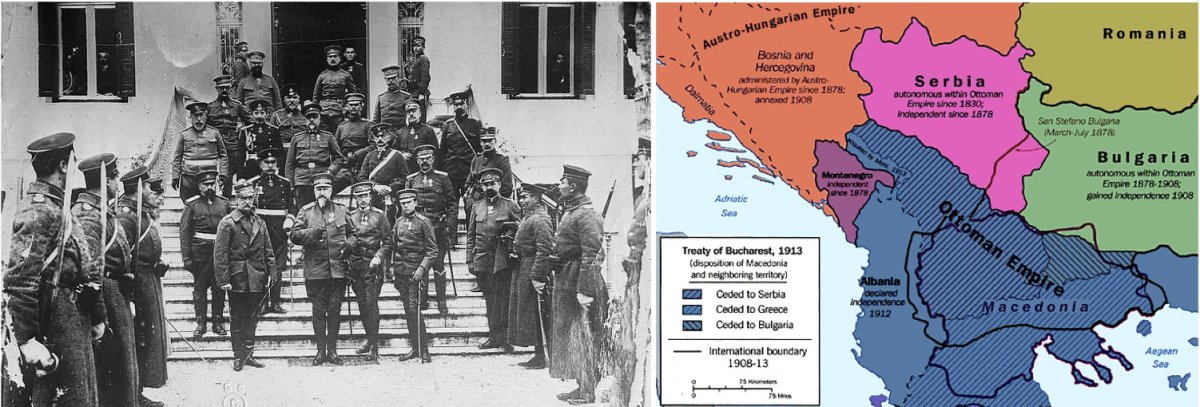

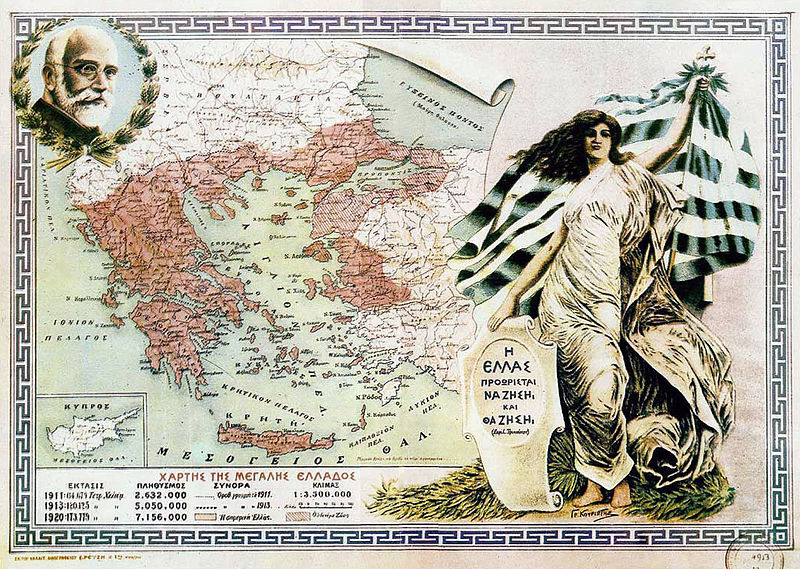

In 1912, war erupted on the Balkan Peninsula when Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Romania pushed the Ottoman Empire out of Europe. When the Balkan Wars ended in 1913, Greece had emerged as one of the largest victors, increasing its territory by more than 40 percent.

King George I of Greece and Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria meeting during the Balkan War in 1912 (left). A map of the territorial changes from the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913 (right).

Not unexpectedly, war and territorial expansion put a strain on Greece’s coffers, but the country managed to stay financially solvent under the commission.

World War I and Still in Debt

It was only a year later that the outbreak of the First World War tested Greek resolve. Although Greece did not formally enter the conflict until 1917, the country was forced to support foreign troops along its northern borders when Britain and France employed a blockade of grain into southern Greece.

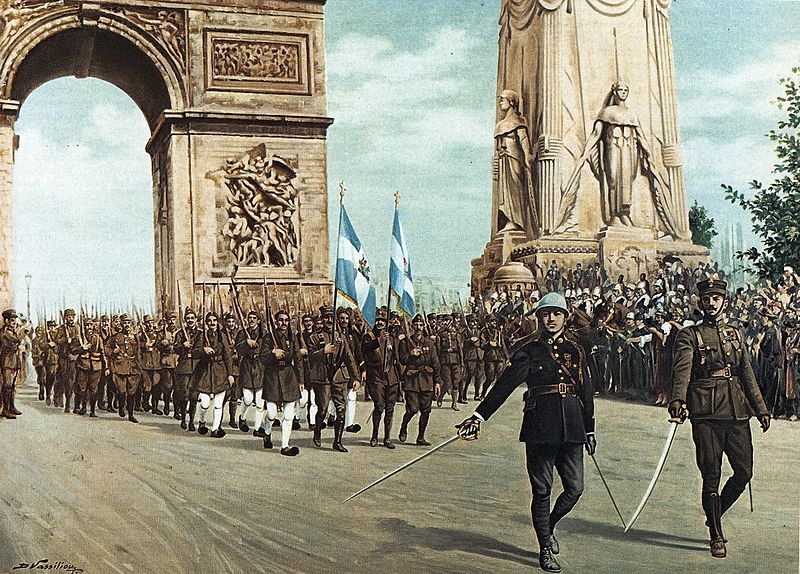

When Greece did enter the war on the side of the allies, the 1918 armistice did not spell the end of conflict. Rather, after being awarded territory on the Asia Minor coast, Greece was once again at war with the Ottoman Empire. This Greco-Turkish War lasted from 1919 to 1922, and the atrocities committed against civilians caught the world’s attention.

A painting of Greek military units in Paris for a victory parade in 1919.

To eliminate what they saw as religious and ethnic conflict between Greece and the incipient Turkish Republic, the world powers imposed a compulsory population exchange. Turkey would receive 500,000 Muslims from Greece, whereas Greece was to receive 1.5 million Orthodox Christians from Asia Minor.

The cost of war and accepting over 1 million new citizens put enormous pressure on Greece and created the perfect storm for another default.

By 1930, the Great Depression caused many countries to default. Already stretched to its limits from the events of the previous decade, Greece once again failed to pay its loans and the Greek government put a moratorium on payments of all outstanding debts.

With a bleak outlook and an economic depression causing ripples across Europe, the International Commission dissolved in 1936 and Greece ignored its foreign debt, choosing instead to focus internally to prevent social unrest.

A Greek lithograph of the Battle of Sangarios River in 1921 during the Greco-Turkish War.

Surviving World War II

Just as the world began to recover from the Great Depression, it was plunged into another conflagration: the Second World War.

Unfortunately, Greece had territory that Italy wanted to annex and on October 28, 1940, Italy issued an ultimatum that Greece hand over territory or face an occupation by the Italian army. To Italy’s surprise, the Greek prime minister, John Metaxas, responded to the ultimatum with a no.

On the same day that it delivered the ultimatum, Italy invaded northern Greece, bringing the war to the Balkans. Greek forces managed to prevent a complete Italian invasion for nearly six months until Nazi Germany came to the aid of its ally. The Greek army was no match for the might of the Axis Powers and was forced to surrender. By the summer of 1941, the entire country was occupied by Nazi Germany, Bulgaria, and Italy.

German soldiers raising their flag over the Acropolis in 1941 (left). A crowd during the deportation of one of the oldest Jewish communities in Greece in 1944. Nearly all of the people deported were murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau (right).

The Nazi occupation of Greece during World War II virtually destroyed an already fragile economy. The occupying forces drained the country’s resources, subjecting Greeks to famine and mass starvation. To make matters worse, the Nazis demanded that the bank of Greece finance the occupation.

By the time Nazi troops were forced out, the country was in shambles. An estimated 90 percent of the country’s infrastructure was destroyed and 300,000 Greeks had either starved to death or been executed during the occupation. The country was drained financially and faced the expensive task of rebuilding.

200,000,000 drachma banknote issued in 1944 during a time of rampant inflation.

Much of the anti-German sentiment regarding the debt crisis observable today stems from this occupation. Germany was ordered to pay heavy reparations, but Greece still disputes that the German payments were ever fully made. That history, paired with the perception that Germany controls the money within the European Union, fuels animus today towards Merkel and the German government.

Just as the country began the task of reconstruction after the occupation, a civil war erupted in 1946 between the liberal government in Athens and communist partisans, plunging Greece into a three-year crisis. With the backing of Britain and the United States, the government of Athens was victorious over the communist partisans, but the country was left in a state not much better than it that of 1944.

From the end of the civil war until 1951, Greece received $700 million as part of the Marshall Plan. While the money undoubtedly helped to put Greece on the path of reconstruction, there is still much debate over how much Greece benefited from the aid.

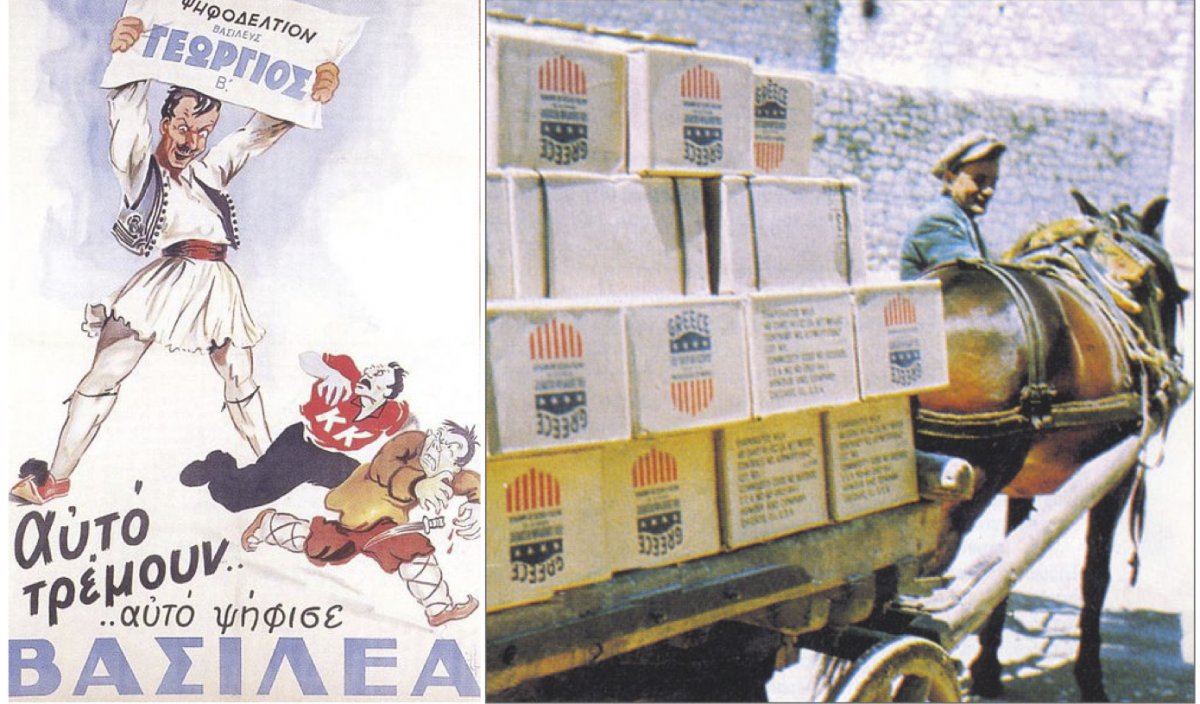

A 1946 anti-communist poster in favor of George II declaring: “This is what they fear! Vote for the King!” (left). A donkey carrying Marshall Plan supplies in Greece in the 1950s (right).

The intent of the Marshall Plan was to help prevent the spread of communism while rebuilding the economies of Western Europe. In the case of Greece, however, when the aid ended in 1951, the country still had an unemployment rate of 20 percent, a worthless currency, and an economy that could not sustain itself.

Therefore, what was intended to be a plan to finally break Greece’s cycle of borrowing and defaulting failed to ensure a positive outlook for the country’s future.

By 1955, Greece was able to stretch Marshall Plan aid far enough so that they only had to take out three additional loans totaling $145 million. The Greek deficit continued to grow during the late 1950s and early 1960s because Greece exported very little while relying on imports to sustain its population, as well as overspending to keep the country in line with western standards.

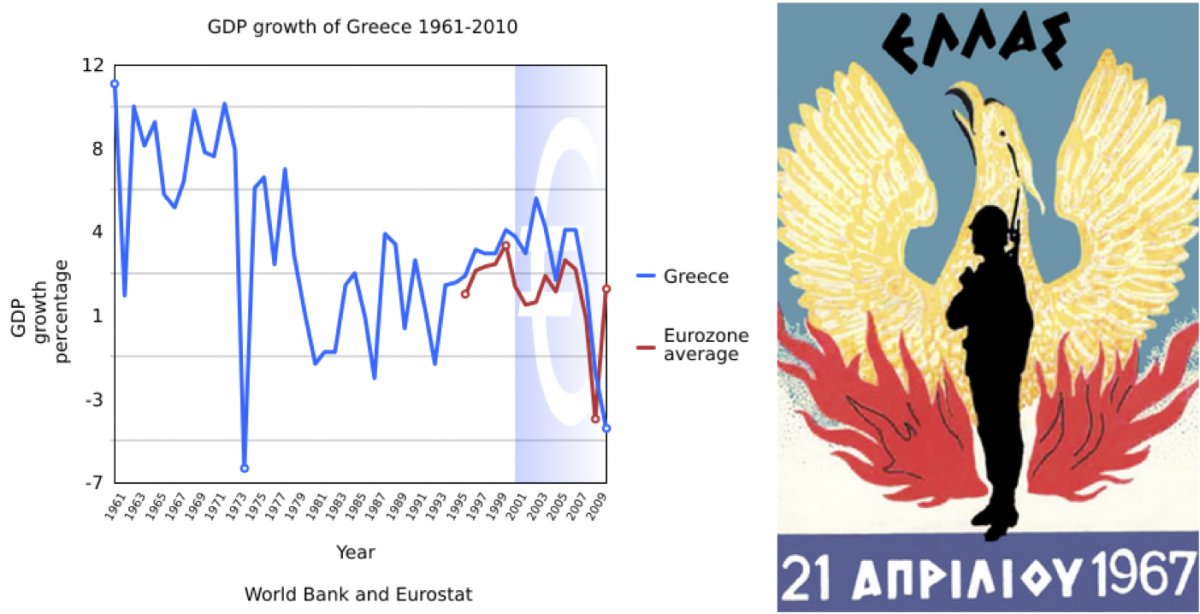

A graph depicting GDP growth in Greece from 1961 to 2010 (left). The emblem of the Greek military junta featured a phoenix rising from flames, a soldier, and the date of the coup d’état (right).

Overspending led to more borrowing—28 loans, to be exact, from 1955-1965—and social and political unrest ran rampant. Violent protests exploded in the streets as many Greeks could not find work or obtain a livable wage. Declining public confidence and the fissures remaining from the civil war led to the takeover of the country by a military junta in 1967. This dictatorship, which lasted until 1974, saw the abolition of the monarchy, reliance on domestic borrowing rather than foreign, and political corruption regarding finances.

More public unrest and demands for liberal freedoms led to the collapse of the dictatorship, but financial corruption under the regime dug the hole even deeper. Internal borrowing had resulted in shady business deals and unfinished building projects since many projects were halted once funding was secured and remained abandoned when the junta ended.

Joining Europe

Despite its ongoing economic crises and growing debt, Greece was admitted to the European Commission (a precursor to the European Union) in 1981. In 1985, it was uncovered that Greece had the highest per capita public debt in the world. This realization caused an already struggling economy to take a nosedive due to a loss of international investment confidence and a bleak economic outlook.

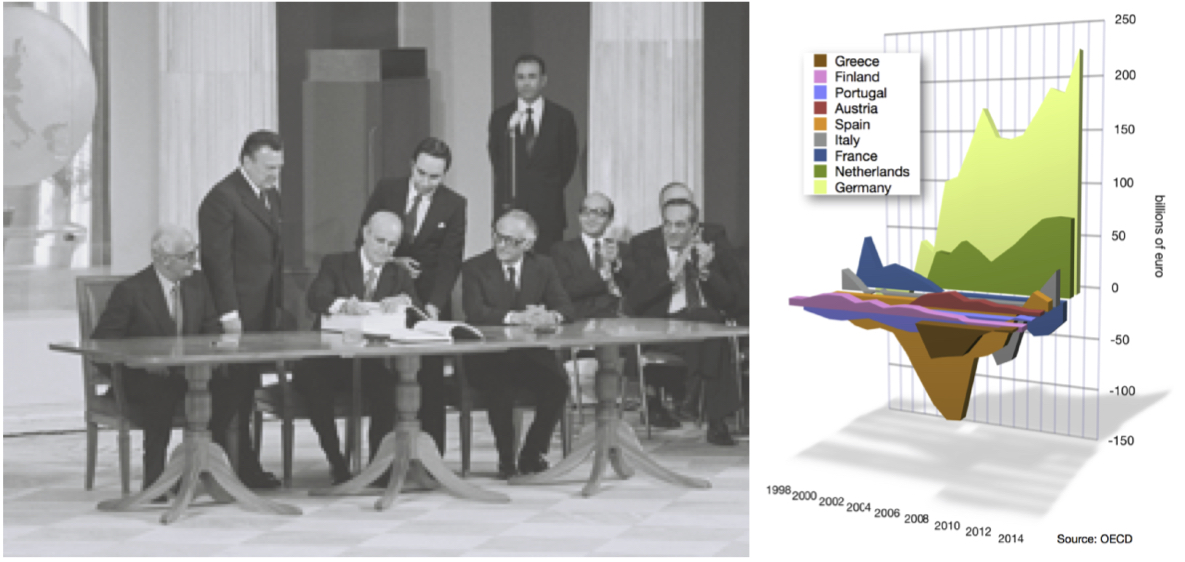

Officials signing the documents for the accession of Greece to the European Union in 1979, a process completed in 1981 (left). A graph depicting account balances and imbalances of European countries from 1997 to 2014 (right).

The result of this severe recession was that, once again, Greece was forced to seek foreign loans to maintain and modernize infrastructure. This trend continued when Greece entered the Eurozone in 2001.

In an homage to its heritage, Athens was awarded the 2004 Olympics by the IOC. This news was well received by the Greek people and the international community because money would be funneled into Greece to help improve infrastructure; and so it did.

Celebrations during the 2004 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece (left and right) and the logo for the games (center).

Before the opening ceremonies, Athens unveiled a new airport, metro system, trolley line, and sports facilities, and much of the city received a facelift. The games brought in millions in revenue through tourism and further solidified Greece as a desirable vacation destination.

This success was superficial. At the close of the games, the Greek government notified the Eurozone that its deficit was much worse than initially anticipated. On top of that, the Greek taxpayer was set to foot an $11 billion bill to cover the cost of the games. After the Olympics, the European Commission placed Greece under fiscal monitoring.

Graffiti in Greece critical of the IMF in 2015.

Greece’s entry into the Eurozone was problematic from the start. Not only did the country fall short of the economic requirements (its deficit was 9 percent above the requirement of 3.9 percent or lower), but wages fell by 22 percent in the years after Greece’s integration into the Eurozone.

The European Commission continued to monitor Greece’s finances, and after the global crisis of 2008, Greece warned the Eurozone that it was on the verge of collapse under a crippling debt load. The severity of the situation was hidden from Eurozone partners because the Greek government falsified data.

The effects of longstanding debt, political misuse of funds, and issues with tax evasion finally caught up with Greece. Tax evasion crossed all social lines as the wealthy hid assets, small business owners manipulated numbers by paying employees under the table, and many Greeks were forced to accept these under-the-table positions while avoiding taxes out of fear of retaliatory measures.

By 2010 the Greek government had no choice but to approach the Eurozone for assistance.

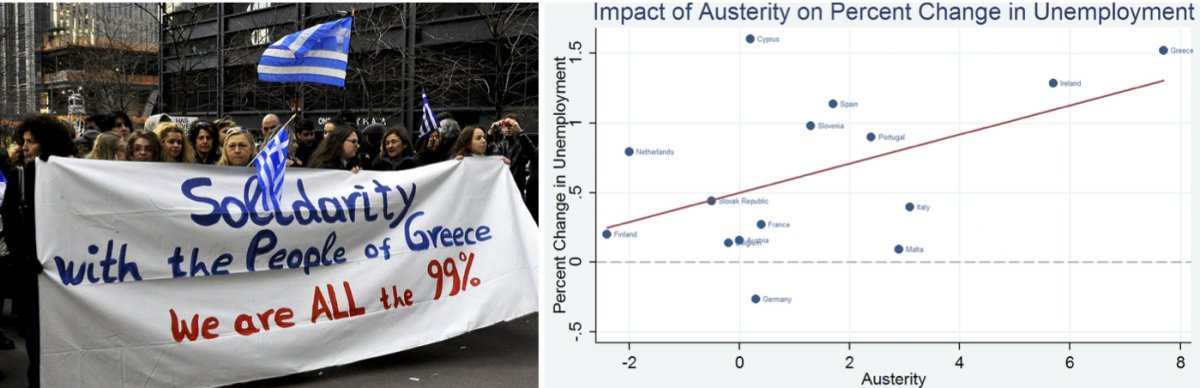

The volatile situation in Greece, and the growing economic woes in other EU countries such as Spain and Italy, stoked fears that a Greek exit from the EU (dubbed “Grexit”) would create a domino effect in the Eurozone and lead to its eventual destruction. This anxiety resulted in the creation of a bailout package to prevent Greece’s demise.

The Economic Adjustment Program, as it was called, proposed 110 billion euros of aid to Greece to ensure the government could cover its necessary expenses and prevent economic collapse. To receive this bailout package, Greece had to reform its tax system, cut unnecessary spending, and reduce pensions.

Prime Minister George Papandreou signed the agreement in May 2010, and the highly publicized deal brought international attention to the Greek debt crisis and sparked global economic fears.

2011 street art in Athens, Greece depicting the country’s financial woes.

Despite governmental reforms, the global recession and concerns in the European banking sector over restructuring Greek debt created more economic problems for Greece. In particular, many feared that the government would not have the money to pay state employees and pensioners.

In turn, this fear of insolvency led to negotiations for a second bailout package from the EU that required austerity measures (slashing of government salaries and reduction of pensions by nearly 40 percent) be put in place to receive installments totaling 240 billion euros. The changes were to be enacted by the end of 2014. The IMF also agreed to provide Greece with another 8 billion euros in loans to be paid from 2015-2016.

2010 May Day demonstrations against austerity measures in Athens (top left and right and bottom left and right). Ruins of the castle of Saint John on the Greek island of Rhodes with "no" graffiti on it representing opposition to austerity measures in 2009 (middle left). An estimated 100,000 people gathered at Syntagma Square Garden in Athens in 2011 to protest the IMF (middle right).

The Eurozone praised the second bailout package as a cure for the debt crisis and economic futures looked promising, with Greece predicting a surplus in 2014. However, as the saying goes, “history repeats itself.” Greece entered another recession at the end of 2014.

The recession and further economic fears caused public unrest and a snap parliamentary election in January 2015. Knowing it was unable to make interest payments under the current terms of the bailout package, the new Greek government began negotiations to prevent a default in June. The European Commission, the European Central Bank, and the IMF—Greece’s creditors—rejected the proposals and would only agree to further negotiations if the Greek government accepted even more austerity measures.

A message on an ATM in 2015 telling customers about the referendum, the closure of banks for one week, and that funds are limited to 60 euros a day (left). A projection on the German Embassy in London in 2015 with the Greek word “no” (right).

Having already implemented twelve tax increases and decreased pensions by 40 percent as part of the first two bailout packages (2010 and 2012), the Greek government feared more public unrest and violent protests. They decided to hold a referendum on 5 July and let the people decide whether to accept the new bailout terms. During the month of June, banks began to close temporarily and limits were placed on cash withdrawals as Greece ultimately defaulted on a 1.7 billion Euro payment to the IMF—the reason I could not withdraw money from that ATM.

The results of the referendum sent shockwaves through the world. In what came as a surprise to people outside of the country—although not to those within it—the Greek people voted against the bailout package, meaning a Eurozone exit was the next step. The results created panic around the world based on fears of a Eurozone collapse and another global recession.

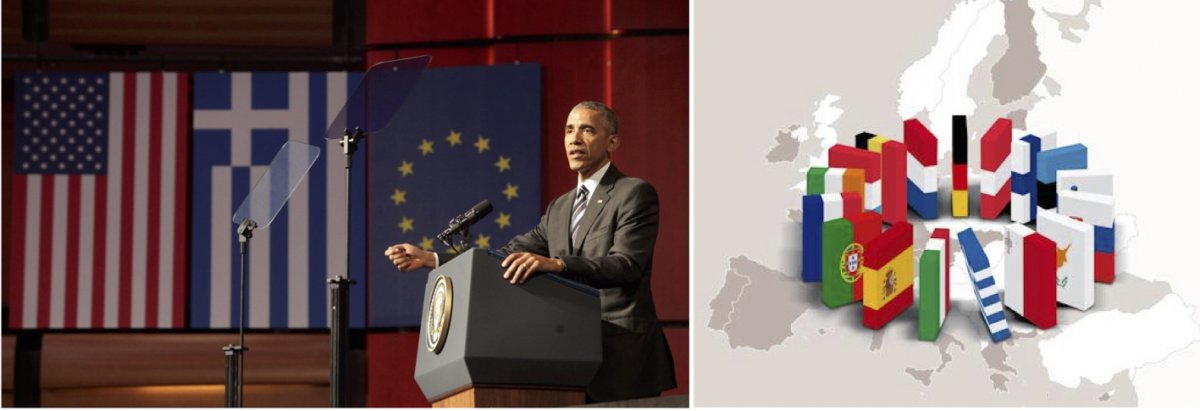

U.S. President Barack Obama speaking in Athens, Greece in 2016 (left). A graphic presented by the Dutch government in 2011 about the European sovereign debt crisis (right).

International leaders began to apply pressure on the Greek prime minister, even prompting a call from U.S. President Barack Obama. Just two weeks after the referendum, the Greek government ignored the public’s decision and began negotiations for a third bailout package. The new bailout carried the same terms that prompted the referendum, and the Greek people prepared themselves for another unwanted wave of tax reforms and spending cuts.

During 2017, the outlook for the Greek economy improved and the GDP was projected to grow by almost 3 percent. However, after introducing terms for a thirteenth austerity package, the debt increased to 250 billion euros. Greece announced that its debt burden was unbearable and it would need to borrow more money to avoid default. The IMF agreed to more rounds of payments if Greece implemented more reforms and pension reductions by June 2018.

The End of the Greek Debt Crisis?

This brings us to today and the recent announcement of a debt resolution.

Under this new resolution, Greek debt will be restructured to allow for more reasonably achievable repayments and loan maturities extended to 2033. A resolution will hopefully prevent a Eurozone exit and provide relief to a country that has an unemployment rate of 20 percent and is experiencing an exodus of recent university graduates who are seeking employment elsewhere in Europe.

While the announcement that a deal was reached originally elicited joy inside Greece, the celebration fizzled out as many Greeks mulled over their past. The history of modern independent Greece leads me to fear that the agreement reached is only a Band-Aid buying a little time. I hope I am wrong, though, for the sake of my Greek friends and family.

Occupy Wall Street Protesters in 2012 supporting Greek resistance to austerity measures (left). A chart showing the impact of austerity measures on the unemployment rate from 2008 to 2012 (right).

As can be gathered from Greece’s complex history, there has been a constant struggle for the country to manage its debts and create a thriving economy since its creation. What emerges is a story that is particular to Greece: a country born into debt and unable to achieve self-sustainability.

Today, instead of financial Band-Aids that remedy only superficially, what Greece needs is more government transparency and a tax overhaul to reform a broken system. If the IMF and Eurozone want to prevent large-scale collapse, then working with Greece to create reform will prove better than throwing more money into the fire.

Graffiti in Athens, Greece from 2015.

There are lessons to learn from the origins of the Greek debt crisis. Overspending, corruption, and a faulty tax system only contribute to the volatility of the economy, lead to civil unrest, and inch us closer to the fiscal cliff. And all it takes is one unforeseen event that disrupts the domestic or global orders to push a teetering economy over the edge into collapse.

With the United States’ growing deficit in today’s global unpredictability, without transparency and safeguards, it might be only a matter of time until it becomes the next Greece.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on Europe: European Disunion; NATO's New Order; The Migration Crisis in Europe; Northern Ireland’s Incomplete Peace; The Ukrainian Crisis; Socialism in France; and The Greek Civil War, 1946–1949

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on The EU: Past, Present, and Future; Road to Europe: The 2015 Migration Crisis; 1989: The Year That Changed It All; The Fate of Crimea; Memories of the Great War; and Armenians, Turks, and the Genocide Question.

Brewer, David. The Flame of Freedom: The Greek War of Independence, 1821-1833. London: John Murray, 2003.

Galbraith, James K. Welcome to the Poisoned Chalice: The Destruction of Greece and the Future of Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016.

Gallant, Thomas. The Edinburgh History of the Greeks, 1768 to 1913: The Long Nineteenth Century. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015.

Kalaitzidis, Akis. Europe's Greece: A Giant in the Making. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Karyotis, G. and R. Gerodimos, eds. The Politics of Extreme Austerity Greece in the Eurozone Crisis. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

Kofas, Jon. Financial Relations of Greece and the Great Powers, 1832-1862. New York: Columbia University Press, 1981.

Levandis, John. The Greek Foreign Debt and the Great Powers, 1821-1898. New York: Columbia University Press, 1944.

Mazower, Mark, ed. After the War Was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation, and State in Greece, 1943-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

Mazower, Mark. Inside Hitler’s Greece: The Experience of Occupation, 1941-1944. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001.

Pasiouras, Fotios. Greek Banking: From the Pre-Euro Reforms to the Financial Crisis and Beyond. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.