The people of Thessaloniki, Greece embrace the enigmatic White Tower as their city’s landmark. Seventy-five feet in diameter, the earth-colored structure of stone and mortar stands over 100 feet tall. The arrow slits in its cylindrical walls as well as the crenellation of the rooftop and its turret exemplify a medieval military fortification. Its image illustrates postcards, coffee mugs and magnets commemorating this relaxed, yet urbane port on the Aegean Sea.

Views of the White Tower in Thessaloniki, Greece.

This fortress now presides over an ahistorical waterfront plaza that provides a gathering place for Thessalonians on sunny days. African and Greek traders lay down blankets brimming with black market sneakers or set up flimsy wagons with cheap jewelry. Young men hawking balloons walk by the tower, while children chase pigeons nearby. Parents sit on the stone walls that embrace landscaped plots of greenery accessorizing the plaza. Bikers whiz along a carefully defended bike lane, and joggers dodge the fisherman casting off into the Aegean Sea.

There is nothing in Thessaloniki that allows visitors to know that a cluster of cylindrical drums much like this landmark exists in the European suburbs of Istanbul, Turkey. Heading on a ferry west down the Bosphorus Straits, the Rumelian Castle Complex seems for all the world like the White Tower’s lost cousins. The Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II commissioned them in the mid-fifteenth century in order to secure Istanbul and end the Byzantine Empire.

The Rumelian Castle Complex in Istanbul, commissioned by Sultan Mehmed II in the mid-fifteenth century.

The Ottoman Empire captured Thessaloniki in 1430 and ruled it until 1912. A young man from Istanbul tells me all Turkish students learn that this city was “the Ottoman door to Europe.” As such, the port became one of the Ottoman Empire’s principal trading centers.

By the early-twentieth century, an imperial census counted 160,000 residents in Thessaloniki. Sephardic Jews were the most numerically and economically significant group. 61,500 residents were Jewish, and thirty-eight of the city’s fifty-four trading companies belonged to Jewish merchants.

About twenty-eight percent of the city was Muslim, and their numbers were on a par with the 50,000 Balkan Christians who would eventually be counted as “Greek.” This nationalist transformation occurred in 1912, when troops from Athens and other areas of the south beat the Bulgarians to Thessaloniki by one day and effectively incorporated the city into Greece after the First Balkan War.

A fire destroyed much of the downtown area in 1917, but remnants of late-Ottoman elegance can still be detected through discerning inspection. The palatial home of Jacob Modiano and his son Ellie is a three-story structure of brick with at least a dozen windows. It now houses the Folklore and Ethnological Museum.

The late Ottoman villa of Jacob Modiano and his son. The building now houses the Folklore and Ethnological Museum.

The residence where the deposed Sultan Abdulhamid II remained under house arrest is the Macedonian Regional Offices, and its broad staircase leads to an embellished three-story building behind a wrought iron gate. Now the headquarters of the Macedonia Regional Offices, you can walk inside it, peering out the windows, wondering if the authoritarian Abdulhamid II looked through the same as he dreamt of regaining his throne.

The Macedonian Regional Offices, a former residence where Sultan Abdulhamid II was under house arrest after being deposed in 1909.

A forced population exchange after the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1920) emptied the city of its Muslim residents. Still, there remain three buildings that once served as mosques. However, Greek nationalists tore down the distinctive minarets that defined an Ottoman skyline in the 1920s.

The desacralized New Mosque became the Archaeological Museum, thus propagating an era that predates Ottoman history. And the Hamza Bey Mosque became a movie theatre that showed porn up until the 1980s.

The former New Mosque, which is now the Archaeological Museum (left), and the Hamza Bey Mosque (right).

The Jewish population, too, disappeared, and a commercial arcade in the old city center now houses a Jewish Museum. Dating to the late-Ottoman era, the stately exterior belies the shock and dread one must process within the building.

The exterior of the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki.

The curators compel visitors to acknowledge antisemitism and the violence wrought by World War II. The German army and their Greek collaborators sent 43,850 Thessalonian Jews to concentration camps during World War II. They razed the Jewish cemetery to expand the city eastward. After desecrating at least 300,000 graves, they used the headstones to pave the streets of the new urban quarters. These broken headstones now line the foyer of the museum, forcing the visitor to begin and end his tour of the building with remembrances of death.

Broken headstones displayed in the foyer of the Jewish museum of Thessaloniki.

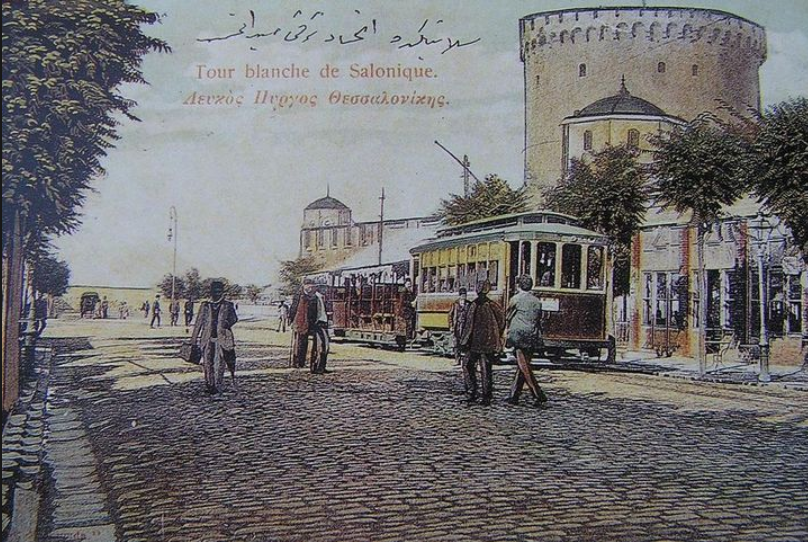

The urban fabric of Thessaloniki today puts forth a distorted narrative, one that largely elides the Ottoman past. A postcard dating to 1907 shows the White Tower as it was just before the First Balkan War. It is surrounded by signs of urban prosperity, cobbled streets, cable cars, street lights, and shop windows.

A 1907 postcard showing the White Tower before the First Balkan War.

Thessalonians today often conceal relics of Ottoman prosperity within the nooks and crannies of their city, tacitly denying the dynamism brought by the rule of an Islamic power from the East.

*I would like to thank Betty Kaklamanidou, Assistant Professor at Aristotle University, Evanghelos Hekimoglou, Curator of the Jewish Museum, and Maria Kyriakidou, General Manager of Easy Guide. Their perspectives on and knowledge about Thessaloniki were invaluable, and their hospitality much appreciated.

[All photos by author unless noted]