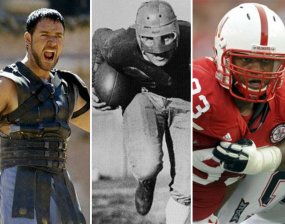

Football player Takeo Spikes compared the violence of football to the Roman coliseum, speaking of the players as “modern-day gladiators.”

The world of intercollegiate athletics is poised on the brink of seismic change. While several cases make their way through the courts that fundamentally challenge the way the NCAA does business, a core group of athletically elite institutions have voted to give themselves more autonomy from NCAA rules and regulations. At the root of how we debate college athletics, Anna McCullough reminds us, are the images we have of the ancient athletic cultures of Greece and Rome. And as she demonstrates, Greece and Rome continue to shape profoundly the way we talk about sports in America.

Read more on Sports: The Sochi Olympics, The World Cup in South Africa, Playing Olympic Politics, and College Sports Reform

And on Rome: Rome’s Rivers and Augustus

Listen to the history podcasts: 4th and Goal? The Past of the American University and the Future of the NCAA; Taylor Branch on the Crisis of College Sports; and The Politics of International Sport

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Gladiators and Football

In a 1973 football game between the Cincinnati Bengals and the Denver Broncos, a pass was intercepted by the Broncos. In frustration, Bengal offensive back Charles Lee “Boobie” Clark struck Bronco Dale Hackbart in the back of the head, causing a severe neck fracture from the blow.

In the ensuing legal case, Hackbart v. Cincinnati Bengals, Inc., 435 F. Supp. 352, (1977), Judge Richard P. Matsch rejected claims of liability against Clark and the Bengals because of the inherently violent nature of professional football, stating in his decision that “There are no Athenian virtues in this form of athletics. The NFL has substituted the morality of the battlefield for that of the playing field.”

Three decades later, San Francisco 49ers linebacker Takeo Spikes also acknowledged the violence of the game, and the necessity of withstanding that violence, as characteristic of football. In response to the recent concern over concussions, he noted, “It’s just the nature of the game. I’ve always looked upon us as modern-day gladiators.”

Athens on the one hand. Rome on the other.

We might ask why references to ancient Greece and Rome pervade our discussions of sport. What are we trying to evoke when we refer to the values and practices of these classical societies? Is there in fact a direct line of influence from ancient Athens, through Rome, to modern America?

The answers to these questions are found in the ways Americans have understood classical culture. In fact, as surprising as it may be to sports watchers and commentators, how Americans talk about sports today is a legacy of how 19th-century Europeans interpreted the classical past.

We hear these classical comparisons especially in discussions about collegiate athletics and the NCAA and in debates over amateurism and professionalism, civility and violence.

The descendants of Greece and Rome are thought to roam on college campuses even in the 21st century, and we continue to look back to them as models for what was done right, or done wrong. It is a debate that started in the 19th century and lawsuits currently fought in the courts are as much between ideas of Athens and Rome as they are between the plaintiffs and defendants.

A Victorian View of “Virtuous” Athens

Since Victorian times, Athens has come to symbolize a set of positive virtues associated with “amateurism.” Rome, by contrast, summons a set of negative associations such as paid athletes and violent spectacle.

The ideals of Athens, according to this symbolic understanding, lead us to civilization and morality. Roman values, on the other hand, take us down the road of depravity and moral decline.

Never mind that these views of Athens and Rome don’t reflect historical reality.

They are instead the product of a Victorian narrative of ancient sport that claimed that the Greeks defined and practiced amateurism according to our modern definition of unpaid participation done for the love of sport—or practiced something enough like it to justify modern conceptions of amateurism as “revivals” of ancient practice.

In the mid- to late 1800s, a newly independent Greece generated significant interest in Hellenic culture and history, leading to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896 and influencing the development of physical education.

Intellectuals in Europe developed a conception of ancient Greek sport: that it had begun as a purely amateur activity of aristocrats, who participated in the Olympics and other competitions solely for the joy and honor of it, and who received no compensation for victory except for a leafy crown and fame. These young men trained both mind and body at gymnasiums like Plato’s Academy in Athens with the goal of instilling the virtue of aretê, “excellence,” as well as a strong sense of civic identity.

In this telling of Greek history, such amateur athletic activity was slowly corrupted by the growth of material compensation and an influx of non-aristocratic participants who trained full-time.

The “professionalization” of Greek sport thus eroded its unique moral benefits by taking the focus off virtue and inviting less worthy men to participate. It also distracted gymnasium attendees from the education offered at those institutions.

This narrative of decline—a descent from morally pure amateurism to morally corrupt professionalism—was presented by historians such as Percy Gardner (1846-1937) and E. Norman Gardiner (1864-1930).

And it was utilized by politicians and intellectuals such as Pierre de Coubertin to justify elitist policies and elevate amateur [i.e. aristocratic] sport above professional [i.e. democratic] competitions. In their eyes, sport was thus an educational and social tool meant to develop and reinforce elites’ moral, social, and masculine values.

Scholars now accept that the modern definition of amateurism did not apply to ancient Athens. While victors at Panhellenic games such as the Olympics only collected foliage crowns as official prizes, they did receive monetary or other material rewards from their home city-states. Specialized, intensive training and diet were also essential in order to win large or prestigious competitions, implying an approach to sport more professional than amateur.

Eroding Athenian Virtues

Despite these new understandings of Greece and Rome, this Victorian-era model of sport and society is not dead. The language of moral decline is used liberally by defenders of the NCAA’s efforts to preserve amateurism as a unique value in opposition to the corrosive influence of professionalism.

For example, in Gaines v. NCAA, 746 F. Supp. 738, 744 (M.D.Tenn.1990), Judge Thomas A. Wiseman stated that “even in the increasingly commercial modern world, this Court believes there is still validity to the Athenian concept of a complete education derived from fostering full growth of both mind and body.” Here amateurism was implied to be a bulwark of virtue against the forces of greed.

The former director of athletics at the University of Michigan, Joe Roberson, cited Greek aretê as the inspiration for modern intercollegiate sport, and lamented that the creep of commercialism moved college athletics “further from its mental and spiritual benefits.”

Even certain scholarly articles—which acknowledge changing definitions of amateurism and repeated attempts to reform college athletics—paint a narrative of moral decline. Sociologist Robert Benford describes early college sports as being organized by athletes, but once older adults began managing and coaching with their “own vested interests … the long downhill slide away from amateurism has continued ever since.”

And Dr. Mark Emmert, current president of the NCAA, warned of commercialism overwhelming the amateur ideal in his testimony during the trial of a class-action suit brought against the NCAA by Ed O’Bannon, Sam Keller, and other former college athletes whose images were used by the NCAA in marketing and commercial materials. Despite Emmert’s statements, the court’s August 2014 decision ruled against the NCAA’s claims to the virtues of “amateur” athletics.

Many Americans thus see amateurism and professionalism as opposing values. Professional athletics are described as bereft of any moral benefit, greater lesson, or social benefit and only amateurism offers the prospect of greater meaning or virtue.

The Violence of Roman Sport

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, imperial Rome was often depicted as a decadent, immoral society that could copy but never approach nor surpass Greek culture and its art, literature, and philosophy.

In sports terms, privileging Greece over Rome meant associating the former with the gymnasium, aretê, and education—a “sound mind in a sound body”—and the latter with slaughter in the gladiatorial arena as mass spectacle for entertainment and profit.

Football is the sport most frequently compared to Roman gladiatorial combat. It is the most popular and profitable sport in the United States, and perhaps also the most aggressive and violent. The 2009-2011 bounty scandal with the New Orleans Saints, rising concern over concussions and traumatic brain injuries, audience demand for ever-bigger hits, and the short lifespan of the typical NFL career are all evidence of the intense physical violence of the game.

But can football truly be compared to the most notorious of ancient blood sports, gladiatorial combat? What is the continuing appeal of rhetoric that utilizes the image of the gladiator? Is the motivation different depending on whether it is meant to describe professional or collegiate players?

In a 2011 commentary in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Oscar Robertson, himself a former student-athlete and former president of the NBA Players Association, explains why he uses the comparison: “Student-athletes are treated like gladiators—revered by fans and coveted by [NCAA] member institutions for their ability to produce revenue, but ultimately viewed as disposable commodities. They are given no ability to negotiate the contents of their scholarships, often punished severely for even the smallest NCAA violations, and discarded in the event they suffer major injuries.”

Here Robertson identifies the most common points of similarity between gladiators and student-athletes: profit (for others), victimization, risk of injury, disposability, and popularity. Together, they are representative of what is often meant when the gladiator is invoked as a figure of comparison.

As Robertson implies when he cites the risk of major injury, the first element of the comparison is violence. A common perception is that all gladiatorial contests in ancient Rome ended with the death of one or more participants, but in fact only 10-30% of matches were fatal. The risk of significant injury, however, was certainly ever-present. Human remains from the gladiatorial cemetery at Ephesus, for example, provide numerous examples of healed wounds.

While football is not armed combat, violence continues to threaten participants’ health. Concussions, significant injuries, and players’ deaths have been part of football since its beginnings.

The NCAA itself was formed partially as a result of a record number of deaths in the 1905 football season. The San Francisco Call listed the toll at 19, with 137 “out of the ordinary” injuries. It also noted that a total of 45 deaths occurred during the previous 5 years. In fact, on November 26, 1905, two died “on the field of battle.”

At that time, reforms were proposed to reduce the number of deaths and injuries. These took the form of standardizing rules as well as issuing regulations to prevent non-student “ringers” from playing on teams for schools in which they were not enrolled.

When Columbia University banned football in late 1905, it cited the sport as “dangerous to human life” through its violence, “harmful to academic standing” by diminishing players’ study time and academic success, and, by the hire of non-students to play for the university, detracting from its academic reputation.

Reform efforts a century ago thus centered around reducing the physical toll of the game as much as on ensuring academic integrity. Today, while equipment has improved so that catastrophic injuries such as skull fractures are much rarer, concussions and cumulative trauma injuries are still common, and scientists have established links between even low-level football hits and brain injury. A number of responses have been proposed, among them the NCAA’s recommendation to limit contact practices to only two per week.

So, violence and the attendant risk of injury at even the collegiate level continue to drive comparisons to Roman gladiatorial combat.

The Poverty of the Modern Gladiator

The second element of the rhetorical association between gladiators and college players is money.

Of course, student-athletes are not paid for their labor, but others make enormous profits from their efforts. This is particularly true for the most lucrative of college sports, football and basketball. The Southeastern Conference (SEC) was the first conference to reap profits of $1 billion, largely on the back of its TV contracts and football successes. The annual NCAA Division I men’s basketball tournament provides the largest source of revenue for the NCAA—in 2012-13, this amounted to $769.4 million.

In the March 2014 Atlantic Monthly, David Berri, professor of economics at Southern Utah University, offered some calculations for the true worth of the year’s top college basketball stars. Determining the revenue for each win, and then how many wins each player produces according to an NBA formula, Berri calculated that Joel Embiid, who went third in the 2014 NBA draft, was worth $777,286 to the University of Kansas. Andrew Wiggins, the number-one pick, was worth $575,565.

These amounts are clearly more than the immediate costs to the university in terms of scholarships, health care, etc. provided to each student-athlete. Moreover, both Embiid and Wiggins exited the university after one year without obtaining degrees, i.e. without the education that the NCAA claims is sufficient compensation to student-athletes.

For many, this amounts to exploitation, one reason for comparing college athletes to gladiators. Most true Roman gladiators—that is, those trained to fight and not criminals or prisoners condemned to execution in the arena—were slaves. And, although they received monetary prizes and other gifts for their victories, the overall profits went to their owners.

This parallel of slave labor is also, like football’s violence, nothing new, and in fact was recognized early in the development of the NCAA and college athletics.

In 1929, the athletic director at Oberlin College, C.W. Savage, was alarmed at the trend he saw in college football: “I cannot believe that educational institutions can much longer permit a chosen few of its students to be trained and exploited like gladiators to amuse the populace and incidentally fill the university coffers.”

Gladiators, like modern student-athletes, incurred the risk of serious injury or death while performing this valuable labor for their masters. Joe Patrice of the blog Above the Law likewise recently condemned the NCAA for tolerating “kids risking injury in the gladiatorial pit for the benefit of universities.”

And like slaves and gladiators, more bodies can always be found to take the place of an injured or dead one. A university can rescind a student-athlete’s scholarship if he or she suffers a career-ending injury or does not perform up to expectations. The scholarship, which is the NCAA’s “payment” for athletic services, is tied to those athletic services. If they can no longer be provided, neither will the scholarship.

The student-athlete is thus caught in the same paradox as the gladiator: in one breath, they are active agents doling out violence, and in the next, passive pawns in a system that denies them any rights or recourse.

This type of exploitation and gladiators’ slave status might create expectations that student-athletes will be cast as slaves themselves. This is not always the case, although race is frequently identified as an issue.

Noted civil-rights historian Taylor Branch in his influential article “The Shame of College Sports” talks about the “plantation” system of college athletics: “Slavery analogies should be used carefully. College athletes are not slaves. Yet to survey the scene … is to catch an unmistakable whiff of the plantation. Perhaps a more apt metaphor is colonialism: college sports, as overseen by the NCAA, is a system imposed by well-meaning paternalists and rationalized with hoary sentiments about caring for the well-being of the colonized.”

The British magazine The Economist went further to describe college athletics as a form of “indentured servitude that enlists poor black men as gladiators, exposes them to grave bodily harm and redistributes the fruits of their labor to fat-cat overlords.”

These general impressions of a system that exploits minorities is supported by a 2013 report of the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education’s Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education. The study evaluated representation and graduation rates of black males on the football and basketball teams of the 76 universities that comprise the six major Division I athletic conferences. Overall, between 2007 and 2010, black men totaled 57.1% of football teams and 64.3% of basketball teams, but only 2.8% of all full-time, degree-seeking undergraduates.

At Ohio State University during these years, black men comprised 2.7% of the undergraduate student body, but 52.9% of the football and basketball teams. The graduation rate of these black male athletes was 38%, which leaves OSU just outside the top 10 lowest rates across all 76 schools. This is also quite low in comparison to the graduation rate at OSU of all student-athletes (71%), of all undergraduates (74%), and of all black men (51%).

So, black male athletes do seem to bear the brunt of the NCAA’s “colonial” system.

“A Gladiator’s Adult Adulation”

The last element of the rhetorical parallel between football players and gladiators is the aspect of popularity. They provide entertainment to the masses, and receive adulation and fame as a result. And gladiators were indeed very popular in ancient Rome.

Graffiti from Pompeii and depictions on objects such as common lamps and mosaics demonstrate the broad celebrity of the gladiators and fans’ knowledge of individuals and fighting styles. Romans did have favorite fighters, and some of the biggest stars could even be lured out of retirement to fight for enormous sums of money.

This aspect of a gladiator’s experience is reflected in modern perceptions of them as athletic superstars and entertainers. Commentator Pius Kamau in a March 31, 2004 Denver Post article argued that recognition itself is a substitute for monetary compensation for athletic services: that athletes are seduced by “the ultimate modern intoxicant – a gladiator’s adult adulation.”

Even in 1929, Savage complained that college football had become “a spectacle of highly trained actors” for whom ever-bigger stadiums were being built; many of which, including OSU’s Horseshoe and USC’s Coliseum, were modeled on Roman amphitheaters and the Colosseum in particular. Beloved “actors” must have the proper stages for their heroic deeds, after all.

But despite their popularity, Roman gladiators also possessed infamia, a state of dishonor or disgrace that resulted in legal restrictions and social ostracism. It meant that however famous they were inside the arena, however well they fought or entertained the crowd, outside the arena they were considered among the lowest of the low in the social hierarchy.

This is a striking difference from the modern stereotype of the coddled athlete whose oversized ego and transgressions, some criminal, are overlooked or tolerated.

Robert Lipsyte writes in an April 2, 1995 New York Times article that the focus on stardom and spectacle have ruined nearly every level of sport, not just professional or collegiate: “Call it a gladiatorial class. Families, schools, towns wave 12-year-olds through the toll booths of life. Potential sports stars—who might bring fame and money to everyone around them—are excused from taking out the trash, from learning to read, from having to ask, ‘May I touch you there?’” For Lipsyte, it is a class of pampered sports stars trapped in permanent adolescence by the lack of any expectations or duties beyond entertaining the public and playing well.

Most recently, Florida State University quarterback Jameis Winston embodied this stereotype in the eyes of critics when he was investigated for rape in 2012-13 and cited for shoplifting in 2014 – but his former high school retired his jersey number in his honor in summer 2014 nonetheless.

America, the New Rome

Adulation and crowd expectations of entertainment turn athletic competition into spectacle, which evokes particular historical associations in American culture with Rome.

In the early 19th century, Republican Rome was held up as a model for early America. Values from that era, austerity and sacrifice for the growth and security of the country, were seen as particularly appropriate for the new nation to imitate.

By the end of the 1800s, however, the model had become imperial Rome after imperialist ideas were boosted by the final subjugation of Native Americans, victories in the Spanish-American War, and the acquisition of the Philippines. The Roman Empire could thus serve, in the words of Margaret Malamud, as “a monitory image of what the States might themselves become.”

This image could be positive or negative, as imperial Rome could evoke tyranny and decadence, à la Nero, or virtuous beneficence, à la Augustus.

This tension was reflected in popular uses of Rome during the era. Roman architectural forms such as the triumphal arch and vaulted ceilings were used, and Roman-style luxury was all the rage in the cities. Public baths, elite banquets, and restaurants such as Murray’s Roman Gardens in New York imitated Rome in their decorations and design, and recreations of Roman spectacles became popular. The Octavian Troupe performed sports and gladiatorial combats. Other groups rendered mythological scenes, chariot races, and acrobatics.

Coney Island also staged a reenactment of the destruction of Pompeii. The moral lesson in this popular spectacle lay in Pompeii’s obliteration as the righteous end to a corrupt, pagan city, a lesson echoed in Imre Kiralfy’s massive stage production Nero, or the Destruction of Rome, first performed in 1888. Picked up by Barnum and Bailey as part of their circus, it included arena events like gladiatorial combat. As Malamud notes, even though gladiators and Nero were symbols of the corruption and decadence that brought down the Roman Empire, Americans could still enjoy the spectacle.

Athletes might call themselves gladiators to bolster their own sense of their strength and honor on the field. But the use of the idea of “gladiators” in the amateurism debate is meant to be critical of the concept and evoke Roman spectacle and decadence—Rome’s fall, not its greatness.

It is not just the violence and the image of fans baying for men’s blood, but the overall specter of moral decline that makes it such a potent comparison.

Of course, that decline is presented in different ways.

For NCAA supporters, moral decline will inevitably result from the final abandonment of amateurism as aretê and civilization give way to professionalism’s profit, corruption, and brutality. Audiences, owners, and gladiator-athletes are all complicit in this decline by choosing money over the moral high ground.

But for NCAA critics, this perspective ignores the fact that college football has always been deadly; always lucrative; always popular. For these critics, decline has already happened in the form of immoral exploitation and excessive violence that has tainted the game nearly from its beginning. Reforms that address those problems will thus reverse (or at least mitigate) that decline.

NCAA: Amateurism is Dead; Long Live Amateurism?

The current context in which this rhetoric is most often used is the ongoing controversy over NCAA policies regarding amateurism and the big business of college athletics.

Even within the NCAA, there is disagreement over its policies and amateur mission, as internal emails and memos submitted for evidence in the O’Bannon trial demonstrate.

Also, in August 2014, the NCAA voted to grant autonomy to the five biggest athletic conferences, opening the door to granting stipends to players or other forms of compensation outside mere scholarships.

These cracks in the façade of previous NCAA insistence on no compensation of any type are significant, but amateurism isn’t quite dead.

The NCAA plans to appeal Judge Claudia Wilkens’ decision in favor of O’Bannon and the other plaintiffs. And testimony by Emmert and others during the trial show that belief still exists in amateurism’s unique ability to build character and instill certain moral qualities.

In other words, some continue to value the ideas of amateurism over professionalism, education over profit, and morality and social benefit over corruptive practice.

Some still prefer imagined Athens to imagined Rome.

Benford, Robert D. “The College Sports Reform Movement: Reframing the ‘Edutainment’ Industry.” The Sociological Quarterly 48, no. 1 (Winter 2007): 1-28.

Gardner, Percy. New Chapters in Greek History: Historical Results of Recent Excavations in Greece and Asia Minor. London: Murray, 1892.

Harper, Shaun R., Collin D. Williams Jr., and Horatio W. Blackman. Black Male Student-Athletes and Racial Inequities in NCAA Division I College Sports. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Center for the Study of Race and Equity in Education, 2013.

Holowchak, M. Andrew, and Heather L. Reid. Aretism: An Ancient Sports Philosophy for the Modern World. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2013.

Kyle, Donald G. “E. Norman Gardiner: Historian of Ancient Sport.” The International Journal for the History of Sport 8, no. 1 (1991): 28-55.

Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2006.

Malamud, Margaret. “The Imperial Metropolis: Ancient Rome in Turn-of-the-Century New York.” Arion 7, no. 3 (Winter 2000): 64-108.

Ancient Rome and Modern America. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Savage, C.W. “The Football Frankenstein.” The North American Review 288, no. 6 (Dec. 1929): 649-52.

“The 1905 Movement to Reform Football.” Chronicling America, The Library of Congress. 29 January 2013. http://www.loc.gov/rr/news/topics/football1.html

Young, David. The Olympic Myth of Greek Amateur Athletics. Chicago: Ares, 1984.