In the wake of World War II, the United States helped to build a set of new international institutions designed to bring peace, stability, and cooperation to the post-war world. They included the United Nations, the World Bank, and the World Health Organization. Yet, many Americans have been suspicious of these institutions. And many American politicians have treated them with hostility, none more extravagantly than Donald Trump. This month, historian Joe Parrott examines this history and explores what the future of American diplomacy might hold.

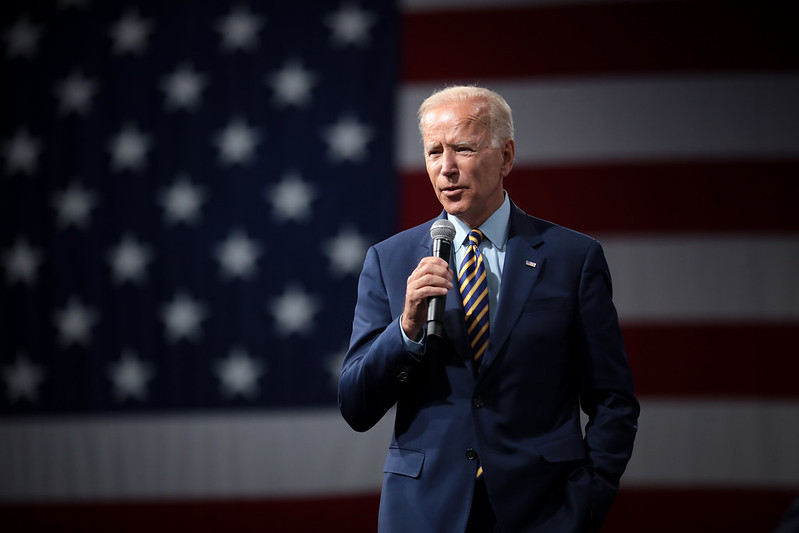

The 2020 U.S. elections have resulted in a new president-elect. Joe Biden will occupy the White House, in part because much of the country rejected Donald Trump. While this backlash was perhaps concentrated on domestic matters and perceptions, Trump’s foreign policy also reflected a polarizing approach to American internationalism that remains popular with a large segment of the country.

Over the past four years, Trump has flouted the authority of international institutions, from questioning the utility of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization to rejecting the Paris Climate Agreement. The latest and most dramatic move was his pledge to withdraw from the World Health Organization (WHO) amid a global pandemic, ostensibly because it did not play hardball with China.

While Trump’s loud rejection of multilateralism has been part of his America First agenda, U.S. administrations have been shifting away from cooperation with international institutions for some time.

Yet many of the world’s most contentious issues seem to demand border-crossing responses. These include not only disease and public health, but climate change, immigration, and global economic inequality.

Understanding why Trump pulled back from the world amid demands for greater collaboration—and why many Americans, particularly Republicans, supported this strategy—requires an understanding of supranational institutions and their relationships with their most important benefactor: the United States.

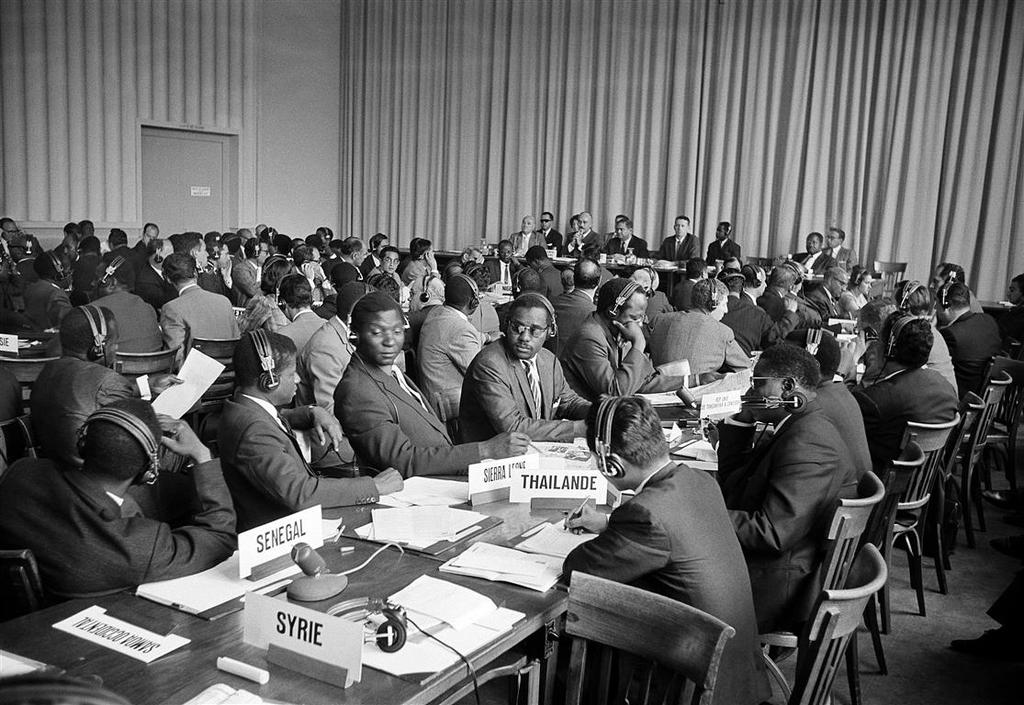

The United Nations Charter Conference in San Francisco, California, 1945.

Beginning with the United Nations (UN) in 1945, the United States helped create institutions that sought to deliver peace, economic development, and social services to the world through an American-friendly model. These multilateral bodies allowed Washington officials to portray self-interested policies as altruistic during the ideological competition of the Cold War.

But these institutions and their goals changed as decolonization transformed their memberships. New postcolonial states and economically marginalized nations in the Global South (Asia, Africa, and Latin America) emphasized policies dedicated to reversing trade inequalities, expanding investment in poorer countries, and promoting multilateralism.

These policies often clashed with U.S. priorities. The gradual loss of control frustrated Washington officials, who complained about the UN and WHO even as they generously funded both. Such frustrations encouraged candidate Trump to argue that Americans were getting a bad deal, an argument he often used to justify his actions as president.

Over the past decades, the United States has struggled to adapt to the more complex, decentralized world that has seen U.S. power diluted. These global changes have destabilized its relationship with multilateral organizations it once viewed as essential for effective management of global challenges such as war and disease.

Looking back on the history of U.S. cooperation with organizations such as the UN and WHO helps explain the current polarized view of supranational institutions, suggesting the country might benefit from working with them more in the future.

The United States and the Origins of Supranational Governance

After two world wars and the Great Depression led to mass human suffering, world leaders and their constituents believed things needed to change. The highly technological and destructive wars made great power politics seem dangerous and erased American confidence in the secure isolation provided by two oceans. The collapse of the integrated global economy proved that nationalistic tools such as tariffs could not protect individual states from hard times.

U.S. leaders came to believe the nation could not remain aloof from the rest of the world. They had long avoided close involvement with European states they viewed as autocratic, corrupt, and warlike. But Washington’s reluctance to coordinate responses to the Depression and the rise of European fascism paved the way for World War II. As a result, U.S. officials began cooperating to construct a new international order even before the conflict ended.

This 1941 poster from the United States Office of War Information depicts the flags of the wartime United Nations. The flags of the "big four," the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and China are in the top row, while the other allies are listed in alphabetical order below (left). This 1943 poster depicts the United Nations as a wartime alliance following the Declaration of the United Nations of 1942 (right).

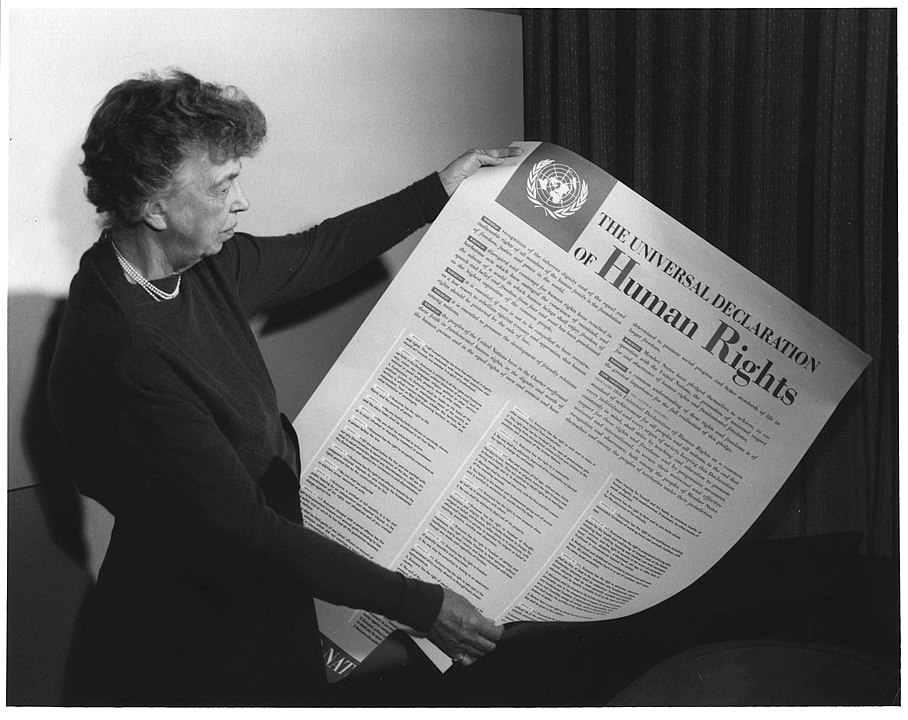

The most visible example of this new direction in U.S. policy was the creation of the United Nations. From the majestic Beaux-Arts War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco, Americans led a group of world leaders in pursuit of the goal that “all worthy human beings may be permitted to live decently as free people.”

The UN was envisioned as a forum on diplomacy, economics, and global norms. At the heart of the institution was a search for collective security, wherein a small council of countries headed by the five permanent members (the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union, China, and France) decided how to respond to violations of international law and custom, sometimes with military and economic force.

In designing this system, the United States willingly forfeited some of its sovereignty in pursuit of a better managed international system. Indeed, it stood willing to sacrifice more by adhering to the majority opinion of the Security Council.

The Soviets, however, demanded each permanent member receive a veto, which the United States approved in order to guarantee Moscow’s participation. While this great-power veto undermined the UN’s ability to act as an effective check on war, the body played a vital role establishing norms of human rights and promoting global economic development.

U.S. support for the UN hinged on the new domestic understanding that national interests across the globe were fiercely entwined. The decades after World War I taught Americans that peace would come not through national defense alone but by removing the largely economic roots of war.

The UN was the centerpiece of an array of institutions seeking to ensure a decent standard of living that would prevent major conflicts waged of necessity, conflicts that would have astonishing potential for destruction after the invention of the atomic bomb.

Two such economic organizations emerged from the 1944 Bretton Woods Conference: the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and what eventually became the World Bank. The former aimed to stabilize currencies through lending to maintain international financial stability and promote trade, in part to prevent another Great Depression. Founded to finance postwar reconstruction, the World Bank shifted to lending to low-income countries after the American Marshall Plan independently provided over $10 billion to rebuild Europe.

These organizations formed the foundations for what is often called the liberal international order. Multilateral institutions promoted democracy, diplomacy, open markets, and managed capitalism in collaboration with a powerful post-World War II United States.

Modernization and the WHO

Central to this liberal international order was another theory whose popularity peaked in the 1950s and 1960s: modernization. Advocates argued that policy interventions could create conditions for rapid modernization, wherein all countries could achieve something akin to the level of economic, social, and political development enjoyed in Western Europe and North America. Improved living standards would provide the foundations for peace and promote further collaboration.

New supranational organizations arose to support this mission, which coordinated international expertise to promote best practices learned from the post-war rebuilding while also extending them to the Global South.

An important example of these new institutions was the WHO, founded in 1948 as a specialized agency within the UN. Wartime destruction of infrastructure, mass displacements, and increasingly rapid transportation bred fears among world leaders that small outbreaks of deadly diseases could spread quickly across the world. They hoped the WHO would help anticipate and prevent such crises.

Based in Geneva, the WHO operated primarily as an advisor to governments and a clearinghouse for information. It had no regulatory power and initially could only respond to requests for assistance from national health institutes. Yet governments participated because the WHO provided information and a level of coordination that they could not achieve on their own.

In the early postwar years, its priorities were controlling communicable diseases and strengthening national programs of health administration, education, and environmental sanitation. This mission was especially vital in the Global South, where European colonial administrators had long ignored national health infrastructures in Africa and Asia. The United States was the largest single contributor, providing almost a third of WHO funding into the 1950s.

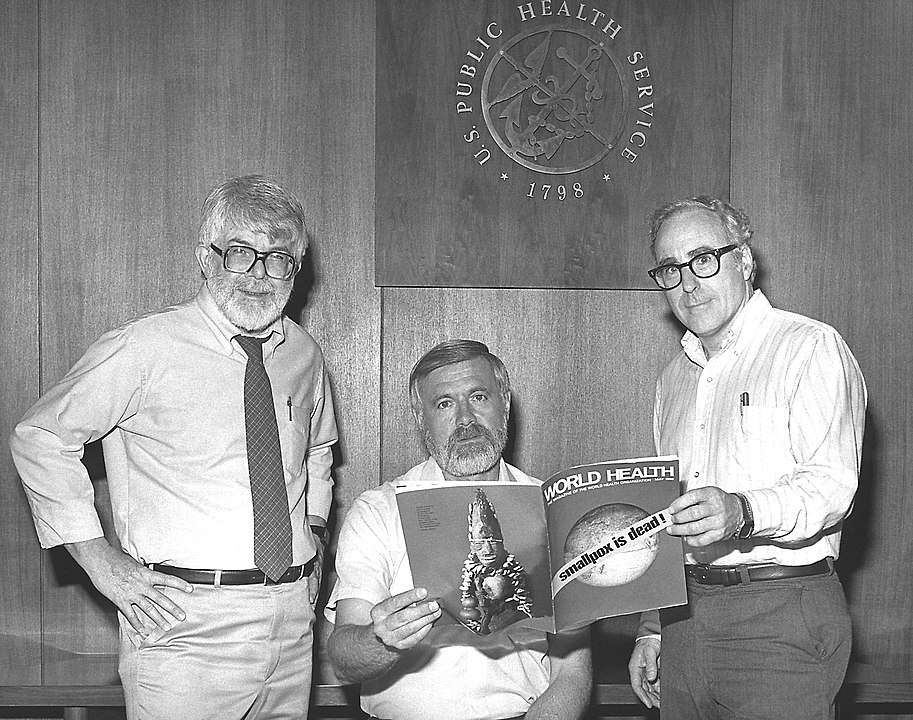

The WHO coordinated global health standards and aid projects, but its role in eradicating diseases tends to attract the most attention. Eradication was far from an obvious goal; experts before World War II questioned whether it was feasible or practical. Yet the postwar era appeared to hold unlimited technological opportunity, especially in the United States. With encouragement from American officials, the WHO argued that the high costs of global eradication of certain diseases—malaria, for example—were justified in economic terms as well as in human lives.

This logic proved convincing. The WHO spearheaded global campaigns, identifying goals and strategies for eradication while also arranging for funds – either through bilateral aid from wealthy countries or in direct grants. There were real accomplishments, if never on the scale early advocates envisioned. The WHO declared smallpox effectively eradicated in 1980, nearly ended the threat of polio, and greatly reduced the number of areas prone to malaria.

Most WHO programs in these early years originated and operated in the global North, but many had a major impact on countries of the Global South as part of the postwar project of development and modernization. Health infrastructures improved substantially, if unevenly. Mortality rates for children under 5, for example, dropped by nearly 75 percent from the 1950s to 1980s in parts of Asia and Eastern Europe.

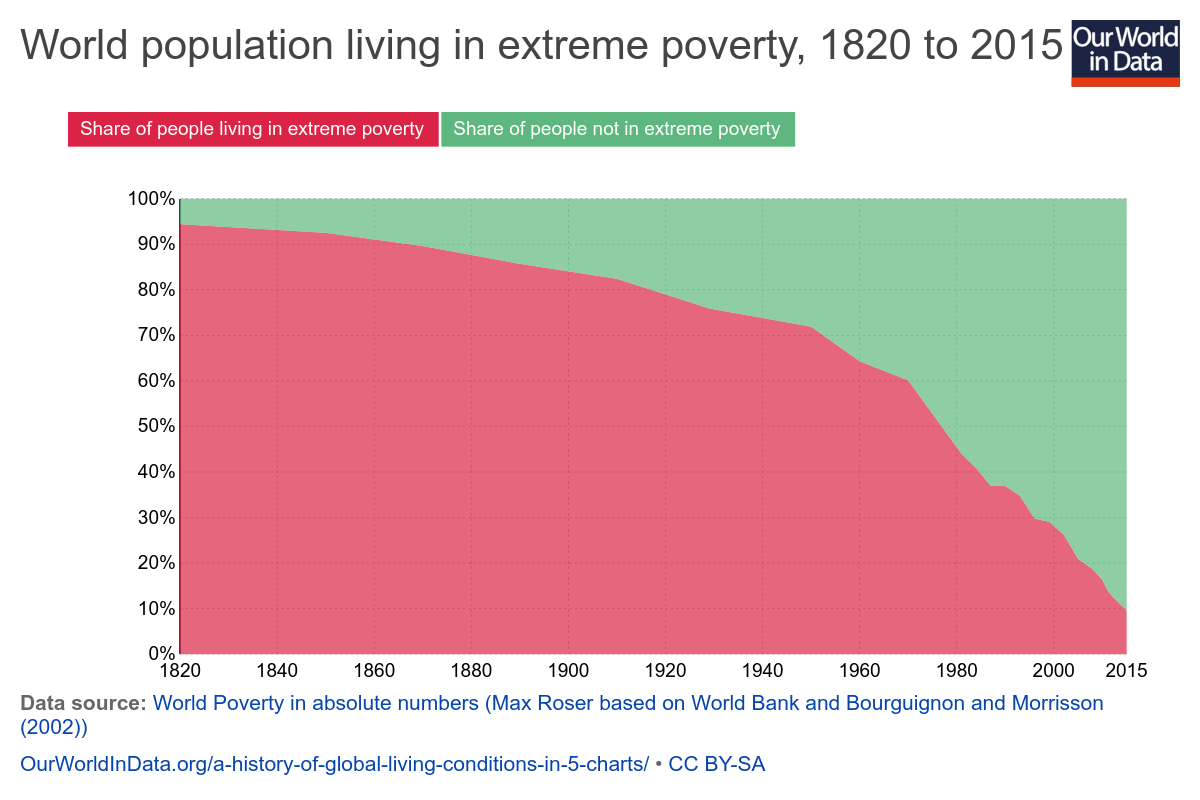

These improvements supported the broader goals of the liberal international order. The combination of aid and investment never reached the 1 percent budget goal envisioned by John F. Kennedy and the UN in the 1960s, but there was progress. Despite lingering and ingrained inequalities, the average 5 percent growth experienced by many Global South countries from 1960 to 1980 greatly reduced rates of poverty. Living standards rose throughout the world thanks in part to American and European assistance.

This level of global coordination and voluntary transfers of wealth was unprecedented. European empires promoted economic and infrastructural development in their colonies as investments for the profit of investors or colonists. Never before had countries transferred even this small fraction of their wealth for the benefit of other nations, nor had they sought to do so in coordinated fashion.

Organizations like the UN and WHO were vital experiments in creating a new international system, in which the benefits of technology, wealth, and knowledge could be more evenly distributed in pursuit of a more just and peaceful world.

U.S. Aid to Supranational Organizations

As the world’s richest country, the United States was the primary benefactor of these institutions and their programs. Why the United States chose to follow this path is complicated.

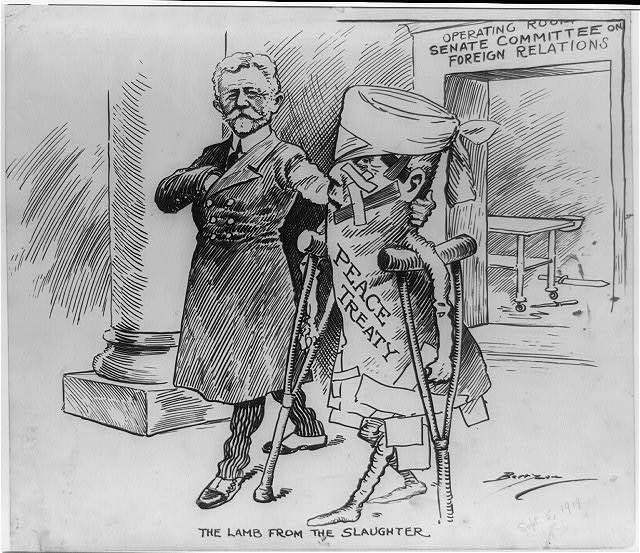

The search for peace and stability through multilateralism provided the basic logic of post-WWII liberalism, but changing the way the United States operated internationally required more than just altruism. After all, U.S. leaders from George Washington onward warned against what Thomas Jefferson called “entangling alliances.” Senator Henry Cabot Lodge defeated Woodrow Wilson’s attempt to join the nascent League of Nations in 1919, launching what would become two decades of increasingly vocal calls for an isolationist foreign policy.

This 1919 political cartoon from The Evening Star shows Henry Cabot Lodge, chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, escorting a battered figure on crutches labeled "Peace Treaty" out of a room. Conservative senators, like Lodge, had concerns over the provisions of the Treaty of Versailles, which provided for the establishment of the League of Nations.

World War II quieted all but the most vocal isolationists, and the Cold War militated against a revival. From 1945 until 1989 or so, the United States became deeply involved in a competition with the Soviet Union, in which it sought to contain the spread of totalitarian communism. That threat motivated both U.S. political leaders and the American people to embrace liberal internationalism, lest ignoring the perceived Soviet threat would repeat the mistakes of the interwar years.

As part of its competition with the Soviet Union, the United States had to prove the superiority of its capitalist, democratic system. It needed to explain to foreign countries why they should adopt, or at least ally with, the democratic, capitalist model of modernization rather than the centralized, state-based Soviet one. This ideological battle focused on individual, quotidian issues such as healthcare, education, and the economy.

The Soviets understood this reality and attacked the United States for everything from domestic racism to poor working conditions. Moscow diplomats argued that these issues highlighted the flaws of the capitalist system, creating economic and health inequities. In response, U.S. investment in economic, social, and health issues—at home and abroad—softened the edges of capitalism and aimed to prove the system was worth defending.

Foreign aid thus became a vital tool in Cold War competition. It supposedly demonstrated both American wealth and benevolence, but the world it promoted stuck rigidly to U.S. models.

When strategically important countries strayed from the prescribed path, the United States could use the promise of aid or combine it with military force—as was done in Indochina—to keep them in the fold. The liberal international order had a coercive military component, which has remained among the most consistent elements of U.S. policy even after the Cold War.

Vietnamese people watch an explosion during the Vietnam War, 1972. Photo by Raymond Depardon.

In this context, support for multilateral institutions like the WHO and specialized UN programs played a valuable role legitimizing American ideas and protecting the United States from accusations that its foreign policy was wholly self-interested. They implied U.S. priorities aligned with international desires.

UN Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge III, the grandson of Wilson’s nemesis a generation before, explained that working with supranational institutions allowed the country to “get credit for practicing altruism instead of power politics.”

The United States expected that these institutions would work hand-in-glove with U.S. policies, and they did so for the first two decades of the Cold War. At the UN, Americans or European allies held key offices; they were willing to compromise because they viewed the world similarly and shared goals. Soviet initiatives antithetical to U.S. visions of economics or healthcare were generally defeated in democratic forums thanks to this Euro-American bloc and a few South American allies.

In less politicized bodies such as the WHO, Western countries dominated senior positions for decades. This gave them extensive control of major programs. For instance, the ultimately unsuccessful malaria campaign initially followed U.S. and European models of mosquito reduction, and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control was central to smallpox eradication in the 1960s.

Through funding and control of administrative positions, the United States promoted orderly, managed development of foreign countries according to U.S. preferences. This “self-interested pragmatism”—as Marcos Cueto and his co-authors argued in their recent history of the WHO—helped justify American participation in these organizations. It also convinced an often skeptical, cost-conscious Congress to fund a quarter to a third of their total operating budgets.

Decolonization and Rise of the Rest

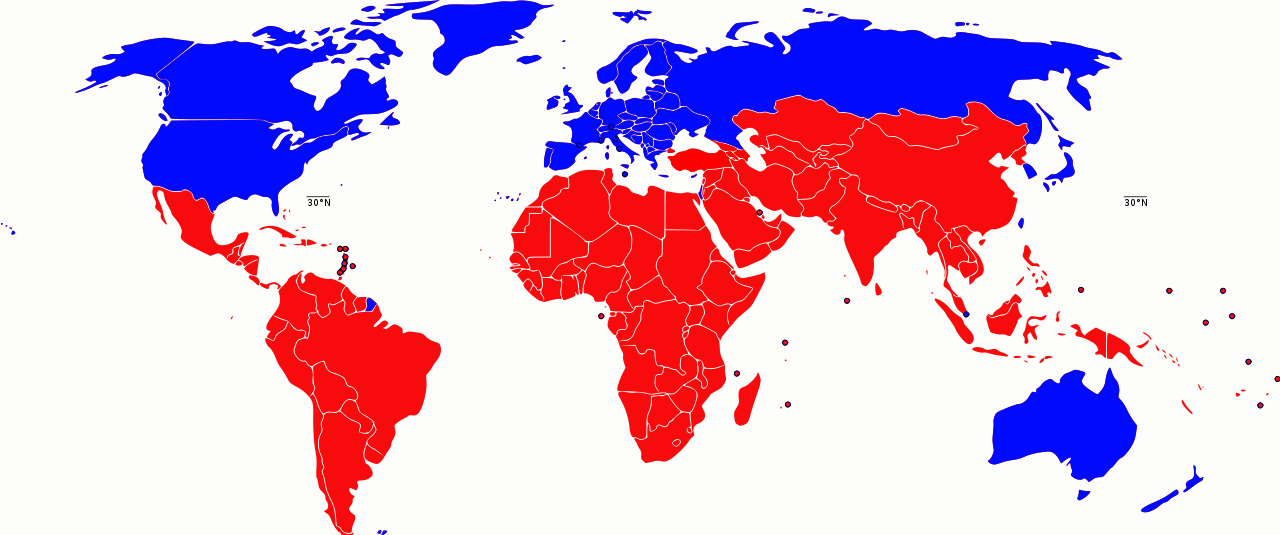

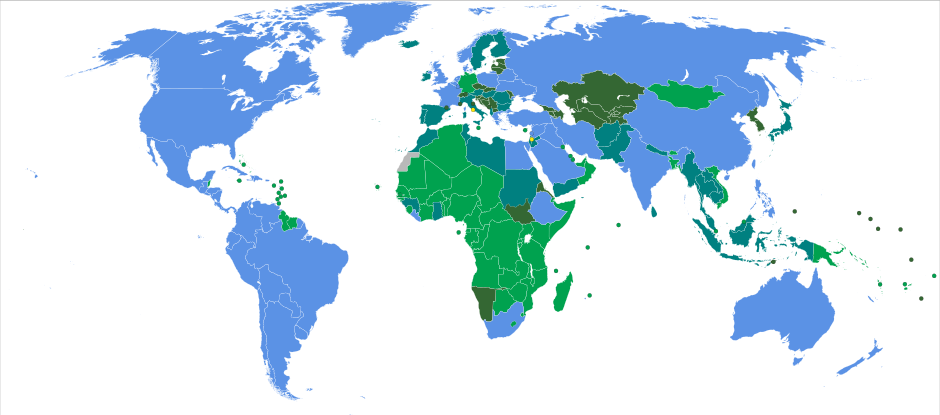

The United States embraced multilateralism because supranational institutions aligned with U.S. priorities, but the explosion of new nations after 1945 challenged U.S. control.

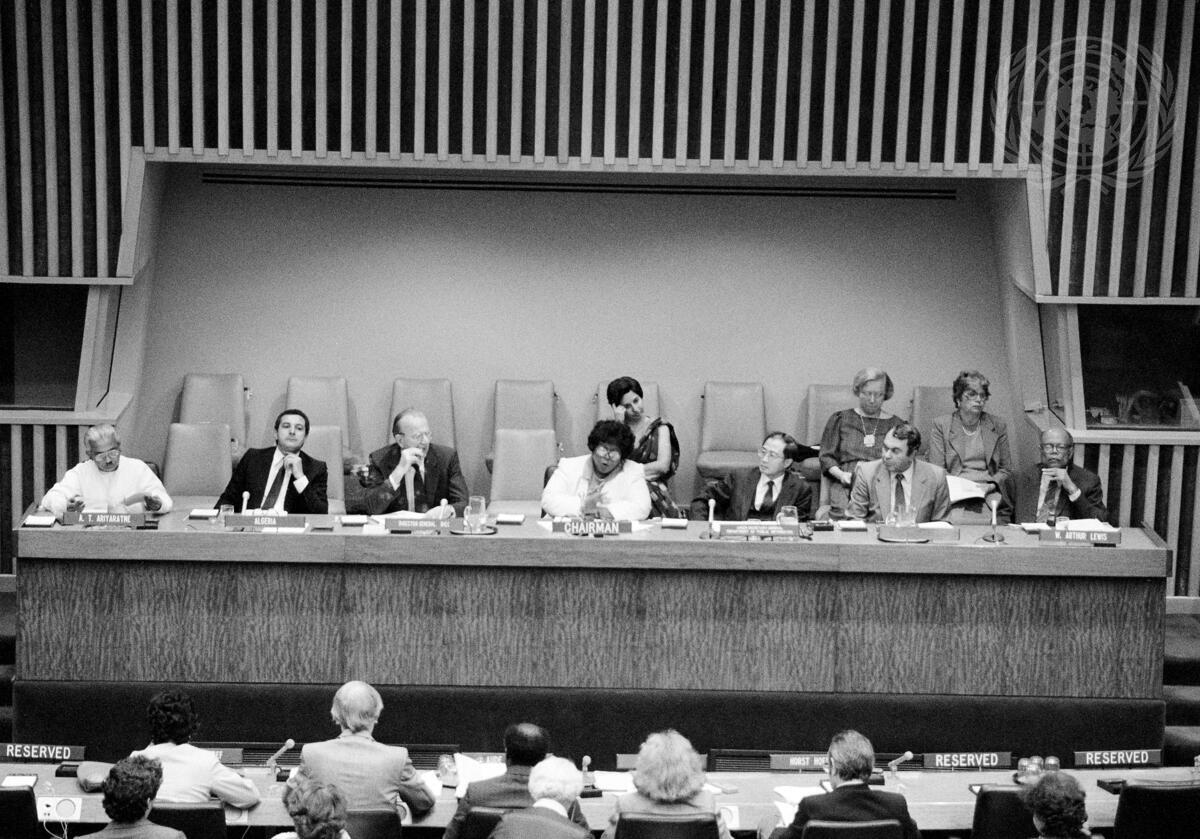

The wave of decolonization that swept the globe from 1947 into the 1970s transformed the UN, tripling membership from an initial 51 to 154 states by 1980. Most new states came from former colonial territories in Asia and Africa and soon outnumbered the American and European countries that formed the bulk of the founding membership.

The addition of these new nations to supranational institutions, including specialized ones like the WHO, changed their internal dynamics in ways that refocused their efforts on the needs of the Global South.

Southern activism led the United States to question the value of bodies like the UN as their policies shifted. Many of the new countries eschewed the Cold War competition. They courted aid from both superpowers and borrowed elements of the planned Soviet economy in the search for rapid economic development. They also looked to place their problems—economic underdevelopment, trade inequalities, the inheritance of weak infrastructures, and structural disparities—onto the international agenda.

They were able to do so because some of the international institutions set up after World War II had strong democratic elements. The General Assembly of the UN, for example, operated according to a one-country-one-vote system. Newly decolonized states downplayed differences to create a powerful voting bloc that prioritized new issues.

The UN became a forum for challenging structural inequalities in the international system that traditionally privileged European and North American countries.

Among the most important initiatives was the UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which advocated a New International Economic Order that empowered Global South states. It sought to boost aid and allow protectionist policies in the developing world to help inefficient start-up industries find their feet. This upended the open market regime established after World War II, which favored advanced industrialized economies that imported cheap raw materials from the Global South.

Similar developments occurred within supranational institutions such as the WHO. Despite real gains, institutionalized bias and top-down technocratic approaches created unequal outcomes between Global North and South. In 1955, for example, the WHO deemed malaria eradication efforts in sub-Saharan Africa premature because the limited colonial infrastructures could not undertake programs designed for Europe and North America.

Global South states responded by demanding more bottom-up approaches to eradication and new emphasis on primary health care. This latter policy embraced social medicine that rejected expensive, technology-dependent Western programs in favor of broad improvements to medical infrastructure and individual health education, promoting prevention rather than just intervention.

The popularity of these approaches from the 1960s onward put the United States on the defensive. The Soviets had long championed primary health care, while small-government politicians and a territorial American Medical Association rejected social approaches to healthcare at home.

The priorities of African, Asian, and Latin American nations were pushing supranational organizations in directions that challenged U.S. priorities.

The Rise of Neoliberalism

Domestic criticism grew as the United States lost influence within these supranational bodies. From the 1960s onward, congressional skeptics seized on these challenges to U.S. visions of development as proof of hostility that justified rethinking foreign policy.

When these organizations crossed political tripwires, such as involving Palestine in UN and WHO deliberations, frustrations boiled over and became political fodder. After the UN admitted the People’s Republic of China in 1971 with the support of many Global South states, Republican firebrand Barry Goldwater claimed: “The time has come to recognize the United Nations for the anti-American, anti-freedom organization that it has become.”

Conservative Republicans and Southern Democrats bristled at supranational organizations trying to set regulations and establish norms, especially when they challenged domestic policies or business interests. In one instance, the Reagan administration drew rebukes from career officials and many Democrats when it voted against a nonbinding WHO initiative in 1981 to restrict the marketing of formula and encourage breastfeeding.

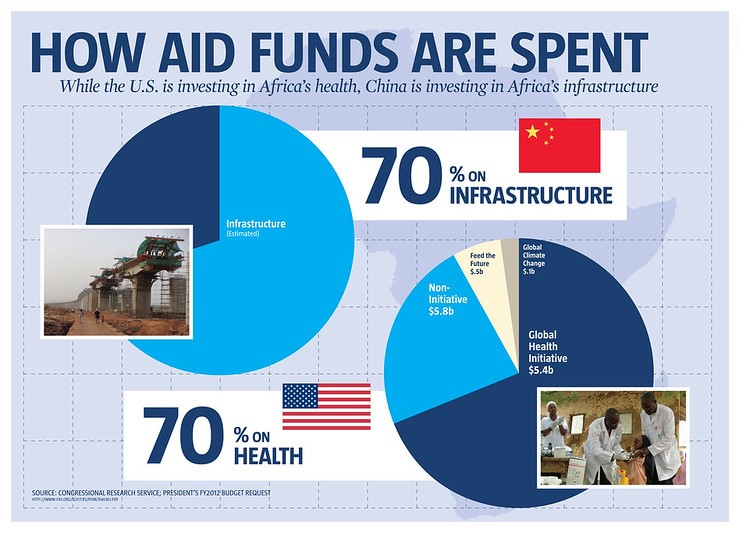

This domestic revolt weakened the U.S. commitment to foreign aid. Bilateral agreements between Washington and individual countries became popular, since they provided the United States with leverage and greater control of projects.

But even here, many politicians viewed recipients of bilateral aid who broke with the United States at the UN or WHO as ungrateful. Led by defense-minded politicians and budget hawks, the Congress progressively cut foreign assistance, buoyed by popular attitudes that supported aid in principle but exaggerated the cost of such programs.

By the late 1970s, foreign aid had become a political issue, wielded by Republicans and conservative Democrats to criticize opponents for being spendthrift or foolish. The popularity of such attacks owed less to the actual costs of foreign aid and multilateral institutions—which never amounted to even 1% of the annual federal budget—but rather to the increasingly common perception of multilateral institutions and nation-states themselves as bureaucratic, inefficient, and wasteful.

This attitude reflected a shift from liberal internationalism to neoliberalism as the dominant American ideology. Neoliberalism prioritized the rational power of markets. It sought to limit the role of states and international institutions to supporting economic exchanges.

This approach fit well with the Bretton Woods lending institutions established at the end of WWII, in which the United States still wielded major influence. Power in both the IMF and World Bank relied on the size of financial contributions rather than majority votes.

The U.S. government nominated both the president of the World Bank and deputy director of the IMF, where a Western European held the directorship until 2019. And in contrast to the UN’s location in cosmopolitan New York City or to UNCTAD and the WHO in Geneva, the IMP and World Bank are headquartered in Washington, D.C., barely a half mile from the State Department.

During a period when critics claimed the UN and other institutions were forums for criticizing the United States, Washington officials could still align the IMF and World Bank with national priorities.

The Board of Governors for the International Monetary Fund (IMF), pictured here in 1999.

Rejecting the demands for change articulated by UNCTAD, the United States positioned the IMF and World Bank to become the primary lenders of monetary and development aid in the 1980s. The conditions attached to loans compelled poor nations to pursue rigid free-market structural reforms that included low tariffs, reduced taxes, fiscal austerity, and the resulting reduction of social services.

These policies fit with the neoliberal economic attitudes of U.S. policymakers and opened small states—concentrated in Africa and Latin America—to trade from advanced industrial countries. It also undermined the diversification of these economies and led to drastic reductions in social spending that had been vital to improving living standards in prior decades.

The neoliberal shift also damaged multilateral institutions like the WHO. Major Western donors—notably the United States—had been trying to rein in spending since the 1960s. The Reagan administration cut the budget and slowed payments as part of a larger effort to minimize the role of the UN and related institutions. In 1985, the United States even refused to pay dues to the WHO in protest of an essential medicines list it believed would interfere in the domestic pharmaceutical industry.

These funding difficulties coincided with the rise of small, non-governmental organizations that competed for funds in areas of development and healthcare. Notable among these were grants given by the World Bank that stressed efficiency through competition, public-private partnerships, and clearly measurable results.

The bank’s neoliberal approach to healthcare emphasized cost-effective interventions such as immunization that revived narrowed versions of earlier practices rather than the more diffuse and equitable primary health care approach demanded by Global South nations.

The economic and public health gains of the postwar period slowed or even reversed in many countries. The 1980s became known as the “lost decade” among developmental economists. Per capita income stagnated in Latin America and declined in Africa.

Austerity measures adopted in these regions and elsewhere exacerbated political divides and promoted radical politics as average people became increasingly disillusioned with sitting governments. Though the weakening of organizations like the UN and WHO encouraged these retreats, U.S. critics used these facts as evidence of their ineffectiveness.

The result is that since the 1990s, the United States has often acted unilaterally or in concert with a limited number of European allies. This most famously occurred in our prolonged wars in the Middle East, but this has also influenced aid programs.

The President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), for example, provided important relief for AIDS-plagued countries, but emphasis on narrow quantifiable goals and domestic political issues—including abstinence-only education under George W. Bush—drew critiques from locals and health experts.

The Future of Multilateralism

After the Great Depression and World War II, the United States embraced domestic and foreign policies it historically had avoided. Multilateral organizations and membership in international institutions were arguably the most important.

Though it sought outsized influence, the country sacrificed sovereignty and willingly compromised with Europeans it had long distrusted in order to pursue shared goals of peace and economic recovery now understood as inherently intertwined with American prosperity.

The benefits were uneven but quite real: improved living standards at home and abroad, avoidance of nuclear war, and global connections that have promoted rapid technological innovation.

But the U.S. drifted away from multilateral cooperation when post-colonial states challenged its domination of these institutions. Since the 1980s, the Republican Party has consciously politicized the issue, portraying most international accords and collaboration with supranational bodies as signs of weakness. This was one reason why Donald Trump heard cheers when he withdrew from the Paris Accords and the WHO.

Yet the decision to prioritize unilateralism does not negate the need for coordination on global issues of economics, disease, climate, and much else. The current pandemic provides an example of just how damaging recent trends towards unilateralism have been.

The neo-liberal defunding of healthcare systems has made tracking communicable viruses more difficult in countries across the world, and there was minimal coordination in the early stages of the virus. Resistance to global guidance and regulation from the WHO further hampered efforts, which exacerbated existing problems in the leadership and legitimacy of the organization, caused partly by decades of underfunding and denigration.

So too has the U.S. preference for technological interventions rather than social ones led to the country’s current crisis. We suffer some of the highest infection totals in the world—and the economic malaise caused by consumer anxiety—while collectively waiting for a vaccine that will take months to distribute once it does arrive.

One question is whether the country will reach the point that it did 75 years ago, when the general public realized a new approach was needed. The other: can the nation find the humility and political will to make the compromises and sacrifices necessary to take an effective leadership role in our more complex, decentralized international system?

We have a new president, but it is unclear if or when the country will adopt the foreign policies necessary to address the challenges of the 21st century.

World Health Organization: History: https://www.who.int/about/who-

United Nations: History: https://www.un.org/en/about-us/history-of-the-un

Marcos Cueto, et. al. The World Health Organization: A History (Cambridge 2019)

Jussi M. Hanhimäki, The United Nations: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford 2015)

Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations: A People's History of the Third World (New Press 2008)

Richard Jolly, et. al. Eds. UN Ideas that Changed the World (Indiana, 2009)

Sara Lorenzini, Global Development: A Cold War History (Princeton, 2019)

Stephen Macekura, Of Limits and Growth: The Rise of Global Sustainable Development in the Twentieth Century (Cambridge 2015)

David L. Bosco, Five to Rule Them All: The UN Security Council and the Making of the Modern World (Oxford 2009)

Alanna O’Malley, The Diplomacy of Decolonisation: America, Britain and the United Nations during the Congo crisis 1960-1964 (Manchester 2018)

U.S. State Department Office of the Historian, Foreign Relations of the United States, Harry Truman: https://history.state.gov/

The 1953 review: Principal stresses and strains facing the United States in the United Nations: https://history.state.gov/