According to the American Zoo and Aquarium Association, there are over 10,000 zoos around the world and each year they attract millions of visitors. But as historian Dan Vandersommers discusses this month, zoos have long been much more than simply places to spend a fun afternoon. Looking at how zoos have changed over the last two centuries can tell us as much about the humans who visit as about the animals on display.

Let’s start with two stories.

On Sunday, February 9, 2014, at the Copenhagen Zoo, a 2-year-old giraffe stretched out its neck toward an inviting piece of bread held between the fingers of a keeper. Marius grasped the treat with his long tongue, pulled it into his mouth, and received a bullet in his brain. Then, before a crowd of zoogoers, including children, Marius’s corpse was cut apart and fed to the zoo’s lions.

This story reverberated through international news. Zoo spokespeople told the world that the giraffe required execution to eliminate its genes from the breeding program. And Danish law supposedly prohibited the sale of Marius despite offers, one of which exceeded half a million dollars. Yet keeping the giraffe would simply be too costly.

Giraffes at the Copenhagen Zoo in 2012 (top left). A sit-in in Lisbon, Portugal in 2014 protesting euthanasia practices on animals for reasons of conservation of the species. The stuffed animal in the foreground represents the case of Marius, a giraffe killed to prevent the propagation of his genes (top right). Harambe, a Western lowland gorilla, at the Cincinnati Zoo in 2015 (bottom left). Harambe and the three-year-old boy who fell into the enclosure’s moat (bottom right).

Animal rights activists shouted, “Inhumane!” and “Barbaric!” In response, one zoo spokesperson stated, “I’m actually proud because I think we have given children a huge understanding of the anatomy of a giraffe that they wouldn’t have had from watching a giraffe in a photo.”

On Saturday, May 28, 2016, at the Cincinnati Zoo, a 3-year-old boy climbed over a fence, crawled through four feet of shrubbery, and fell into the watery moat surrounding the gorilla enclosure. Though, at the keepers’ beckoning, two of the enclosure’s three inhabitants moved indoors, Harambe (a 17-year-old, 450-pound Western lowland gorilla) went to investigate the splashing child. He then clasped his fingers around the boy and dragged him quickly and powerfully along the moated perimeter, onlookers screaming all the while.

Harambe showed signs of stress. His legs and arms were extended stiffly as he made his body look larger. Harambe also showed signs of care—delicately standing the boy up, sitting him down, propping him up, and pulling up his pants. Though Harambe’s intentions can never be known, one fact was clear. The small boy, in the hands of an adult gorilla, was in a life-threatening predicament.

The gorilla habitat at the Cincinnati Zoo in 2016.

Zoo officials decided that they must kill the gorilla. With a single shot, a keeper, from the side of the enclosure, put a bullet into Harambe’s brain as the boy sat between his legs.

Harambe’s death sparked an international controversy. Some blamed the incident on the boy’s mother. Others blamed the incident on the zoo for faulty enclosure design. Regardless of Harambe’s intentions, some argued, zoo officials had no right to kill a gorilla who had done nothing wrong. Still others posited that the wrongdoing lay not with any particulars, but lay embedded in the very idea of a gorilla enclosure. Should zoos even have gorilla enclosures in the first place?

It should come as no surprise that zoos make headlines. According to a 2013 report, U.S. zoos attract more than 160 million visitors annually, more than do all NBA, NFL, NHL, and MLB games combined. These zoos also contribute almost $20 billion to the GDP every year while supporting almost 200,000 jobs.

And this is only the American side of today’s zoo story. On a global scale yearly attendance figures are estimated at around 675 million. There is no doubt that zoological parks are one of our contemporary world’s most popular cultural institutions. There is also no doubt that zoos represent a profitable business and a global industry.

Crowds gather to watch an aquatic show at the Singapore Zoo in 2012 (top left). Thousands attend a music festival at the Albuquerque BioPark Zoo in 2002 (top right). Onlookers watch the elephants at Dublin’s Zoo in 2014 (bottom left). Children and adults walk through the tunnels of the Dallas World Aquarium Zoo in 2014 (bottom right).

Yet the zoological park is a peculiar institution indeed, an industry based not around the consumption of electronics or energy, foodstuffs or retail goods, transportation or health services, but instead based around the long necks, sharp teeth, bright colors, gargantuan sizes, ivory extremities, spots, scales, and stripes of living, breathing, yet commodified animals.

Like most of the culture that surrounds us, we take zoos for granted. We forget that it is not natural to contain thousands of animals within artificial enclosures built in the heart of our largest cities. We forget that zoos have a history. And uncovering this history requires an archeology of sorts. Stroll with me through the zoo. Let’s see what stories lay beneath its entrance gate, its animals, its enclosures, its visitors, and its encounters.

The Entrance Gate

Humans placed animals on display long before they strolled through the entrance gates of zoological parks. In fact, the birth of the menagerie (a collection of wild animals for the purpose of exhibition) began with the birth of the city. Menageries emerged with them as symbols of power and wealth.

Whoever wielded power in the ancient world (whether Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Indian, Chinese, Greek, Roman, Persian, Arab, or Mesoamerican) also established collections of exotic animals in order to display their wealth, status, imperial ambition, and military might. When Hittite kings displayed lions, tigers, wolves, leopards and bears; when Egyptian Queen Hatshepsut displayed rhinoceroses, giraffes, and greyhounds; when Emperor Wu Di displayed elephants, yak, giant pandas, cormorants, and herons; and when Montezuma displayed jaguars, eagles, and snakes, what they really displayed was their ability to conquer their enemies, conquer geography, and conquer nature.

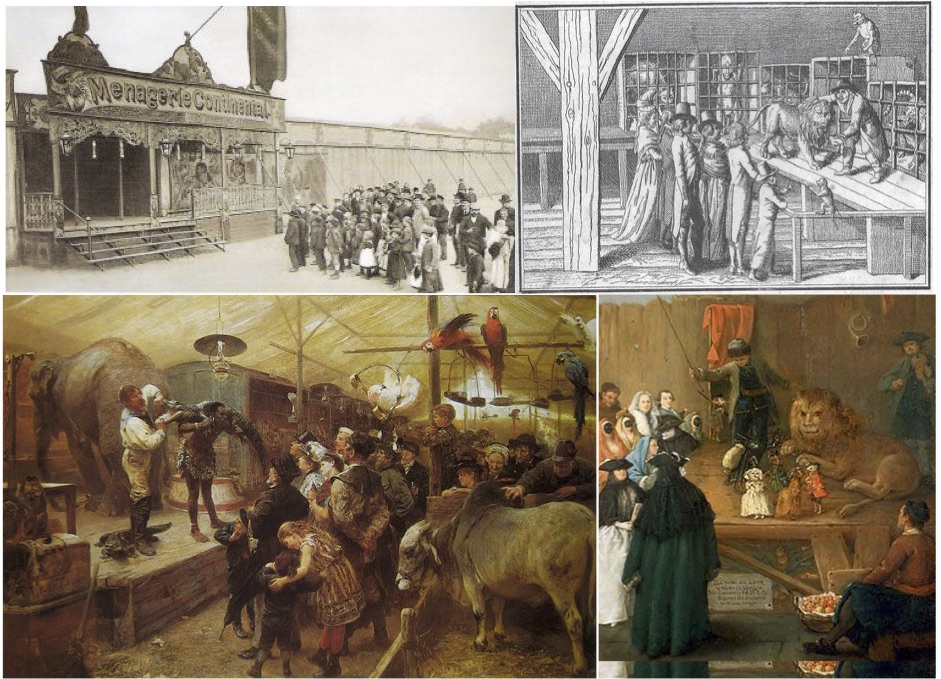

For most of their history, menageries were crude establishments where collections of animals lived short lives in small cages. Yet as cities multiplied, so did the number of animals behind bars.

When the ancient, medieval, and early-modern upper classes fell in love with captive animals, they forged a global trade in animal commodities. To their eyes, exotic creatures from faraway lands appeared luxurious and spectacular. No king would be worthy of his crown without an elephant or a zebra on hand.

While merchants captured, shipped, and sold legions of animals to these royal collections, traveling fairs carted elephants, rhinoceroses, giraffes, and hippopotamuses from town to town for local entertainment.

The royal menagerie of Versailles during the reign on Louis XIV of France (1643-1715).

Exploration and empire-building expanded the reach and symbolic importance of the menagerie. Exotic animals became the playthings of empires. In 1493, 1494, and 1496, Christopher Columbus, for example, gave sixty parrots and a macaw to Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand, setting a precedent for stocking European menageries with New World animals.

Throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, iguanas, bison, guinea pigs, llamas, turkeys, Muscovy ducks, squirrels, and many species of birds flooded Europe. And these animals came to European menageries from all directions. In 1515, Sultan Muzaffar Shah of Malacca sent the governor of Portuguese India a rhinoceros as a gift between friends. The governor then re-gifted it to Dom Manuel I, king of Portugal. All of these animals were showcased as symbols of royal wealth and power.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, as nation-states replaced kingdoms, the bursting menageries evolved from private collections to public collections, supported by taxes instead of individual coffers.

At this moment of intense population growth, industrial revolution, urbanization, and the creation of a European and American “middle class” with expendable income, public animal collections acquired new symbolic meanings. They also acquired new names. Known as zoological gardens, zoological parks, and colloquially as “zoos,” public animal collections still symbolized wealth, empire, and power.

Carl Krone’s circus exhibit, the Continental Menagerie of the Crown, in 1884 (top left). A traveling menagerie in Germany around 1800 (top right). An 1894 painting of a German menagerie show by Paul Friedrich Meyerheim (bottom left). A 1762 painting of a lion exhibit in Italy by Pietro Longhi (bottom right).

However, zoos were also legitimated as institutions that would enrich citizens by providing them with a scientific education, with a place for amusement and entertainment, with a garden for escaping the noise, pollution, and bustle of the city, and with a nationalizing experience. As citizens strolled through a public zoo, they symbolically strolled through a nation and its possessions, economies, sciences, and “civilizing” pursuits.

The evolution of menageries into zoological parks took a century, and in some places, much longer. In 1793, after the French Revolution, this process began when the Jardin Royal des Plantes (the former menagerie of King Louis XIII) was transferred from royal to public ownership. In a few decades, other zoos opened their doors in cities like London, Dublin, Antwerp, Melbourne, and Philadelphia. And by the end of the nineteenth century, zoos had spread the world over.

Even though zoos began to replace menageries, elements of the latter remained commonplace: especially the simple cages of confinement and the symbolisms embodied in their bars. The lions who paced the perimeter of their zoo cages (a common sight in zoos until the last quarter of the twentieth century) would not have known that their captivity was centered in a “new” institution.

The monkey cage at the Schönbrunn Zoo in Vienna, Austria around 1910 and 1898.

Nonetheless, as public zoos become common sights in cities, they became large and complex institutions compared to their privately owned predecessors. They grew in size, housed more animals, and established international markets in those animals.

They employed more humans—staff, professionals, laborers, veterinarians, and zoo keepers. They built more buildings. They organized events. They designed advertising campaigns. They purchased the latest technologies. They opened restaurants, rides, concessions, and souvenir shops. They waved banners for the “advancement of knowledge”—scientific, medical, artistic, technological. Indeed, by the turn of the twentieth century, any pursuit labeled “modern” could have been found on display in the zoo.

The Animals

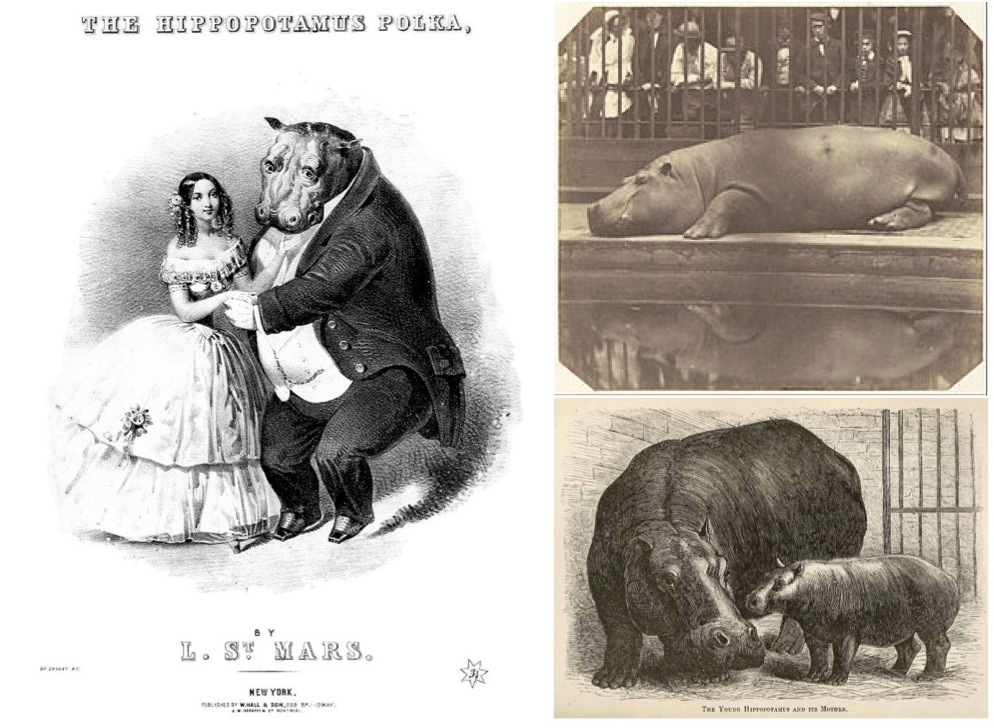

Zoological collections had long needed exotic creatures, spectacular animals from distant continents rarely seen by urban publics. Exotic animals served as the lifeblood of the zoo. When the London Zoo acquired Obaysch in 1850, it not only obtained a large male hippopotamus to add to its zoological collection, but it also received a new representative of empire.

Obaysch had spent most of his life as imperial currency, for he only ended up in London after the Ottoman Viceroy of Egypt gave him to the British Consul General in exchange for some greyhounds and deer. Obaysch became a London celebrity instantly, and zoo attendance doubled during the year of his arrival.

Sheet music for “The Hippopotamus Polka” published in the early 1850s (left). Crowds watching Obaysch, the London Zoo’s first hippopotamus in 1852 (top right). Adhela, Obaysch’s partner, and Guy Fawkes, their only surviving offspring in 1873 (bottom right).

The story of Obaysch is the story of countless zoo animals. Some of these—especially members of the largest and most popular species (known as “charismatic megafauna”)—received individual names and became local stars. The London Zoo, at various times in its pre-1950 history, displayed Jumbo (a male African bush elephant), Winnipeg the Bear (an American black bear), Guy (a western lowland gorilla), and Brumas (a polar bear).

Not only were zoo animals baptized with names, but they were also given cultural lives that transcended their own. Jumbo became the famous circus elephant of P.T. Barnum. Winnipeg became the prototype of A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh. Guy became a London attraction for more than 30 years and was studied for the production of the classic film 2001: A Space Odyssey. And Brumas attracted 3 million visitors to the zoo in 1950 alone, an attendance record that still has not been topped in London.

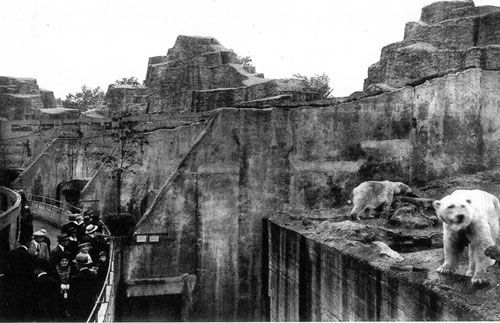

Polar bears at the London Zoo “Bear Pit”.

Every “modern zoological park,” whether in Frankfurt or Tokyo or Moscow or Budapest or Philadelphia, had its own celebrities, its own versions of Jumbo, Winnipeg, Guy, and Brumas (and zoos still do today).

Zoo animals also came to serve increasingly as symbols of conservation. During the two decades before and after 1900, as conservation and environmentalism spread throughout the West, zoological parks and their animals gained a new significance. Zoos came to be viewed as refuges for species facing extinction, the animals valued not only for their exoticness but also for their rarity and vulnerability. On these grounds, “endangered” animals found homes in zoos.

American zoos, especially, sought to save North American animals—like elk, beavers, condors, bison, moose, passenger pigeons, caribou, antelope, mountain sheep, manatees, mountain goats, grizzly bears, elephant seals, and walruses—from annihilation.

William Temple Hornaday with a bison in the New York Zoological Park in 1886.

Worldwide, though, zoological parks collected (and in so doing, sometimes further threatened) animals on the brink of disappearance. Some species’ last representatives, or “endlings,” (like the thylacine, known as the Tasmanian tiger, the passenger pigeon, the quagga, the Carolina parakeet, and the heath hen) died in the confines of zoological parks.

However, expiration was not always the fate of these species. As early as 1903, for example, zoo director William Temple Hornaday acquired 40 American bison to form a zoo-herd in the New York Zoological Park, located in the heart of the Bronx. As a longtime conservationist and nature writer, Hornaday directed public attention to the near-decimation of American bison at the hands of white hunters during the second half of the nineteenth century, and he devoted a career to advocating for their protection.

After acquiring the zoo-herd, Hornaday utilized the NYZP as a place to rehabilitate the species by not only breeding bison in captivity, but also by releasing them onto the Great Plains. In 1907, Hornaday spearheaded the first successful reintroduction of bison when his zoo sent 15 of them to the Wichita Mountains Wildlife Refuge.

Polar bears around 1910 in the Belle Isle Park Bear Pit in Detroit, Michigan.

Over the course of the twentieth century, zoological parks increasingly bred animals on site. While the vast majority of these animals would not (and could not) be introduced or reintroduced into natural habitats, this trend did mean that the populations of zoo inhabitants would become more captive-bred than captured.

No matter what they meant to their human captors, zoo animals always had their own intentions. Zoo animals attacked. They ran away. They made demands. They resisted control. They refused to live out the scripts they were given.

The zoological park was an unpredictable place, as a quick look at the first eight years of the Philadelphia Zoo, from 1874 to 1882, shows. A bison trampled the fence surrounding its pasture in order to charge the elk in the neighboring exhibit. A seal climbed over the railing surrounding the seal pond and wandered into the neighboring pond. A kangaroo broke one of its legs attempting to jump out of its enclosure after being frightened by the sound of a nearby locomotive.

“Jim,” the Bengal tiger, grabbed the tail of the tiger in the adjoining cage, “dragged it in until he could seize its leg,” and ripped the thigh-bone from its socket, killing the victim. A Macaque, or pigtail, monkey tore another primate in half with its hands, and had to be quarantined in its own cage marked with a sign warning zoogoers to keep a safe distance from the bars. An elephant tried to “crush” his keeper “against the bars” of the exhibit. And a young boy climbed over the railing of the open cages where the lions sunned themselves, and barely made it out alive. The global history of zoological parks is composed of countless events like these, wherein zoo animals assert themselves.

The Enclosure

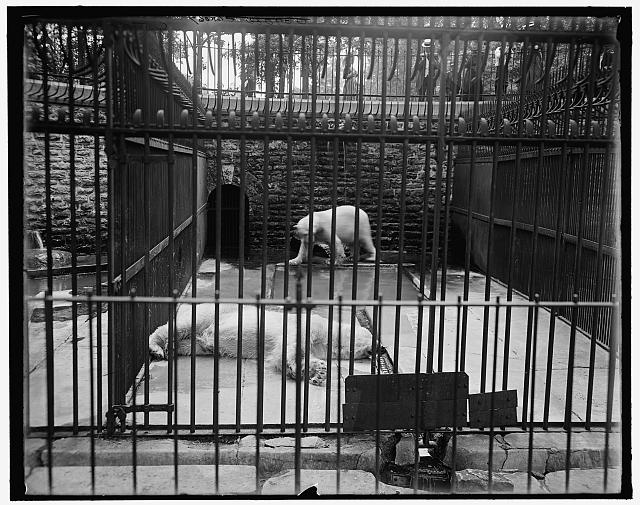

Of course, zoological parks sought to control animals’ independent action and freedom. Throughout the history of animal display, individual animals—whether monkeys, panthers, ostriches, or bison—were showcased in cages, like items of a museum display, polished and arranged neatly for the human viewer. These cages were cramped, pitiful, and soporific. And the lives lived in these cages were always monotonous, defined by lethargic pacing and dreary inactivity, and unsurprisingly these lives were frequently short.

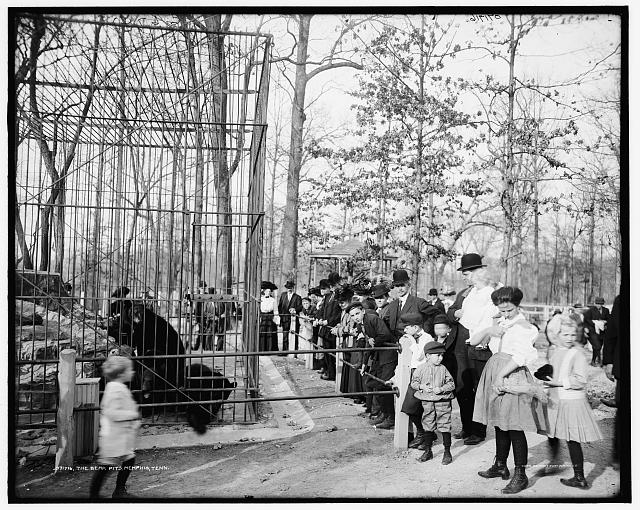

Not only were caged animals made subject to the relentless gawking, teasing, poking, prodding, feeding, and abuse of human onlookers, but they were also vulnerable to the relentless diseases that swept through cities. Cages are nearly universal in the long history of animal display, and they still fill many zoological parks today.

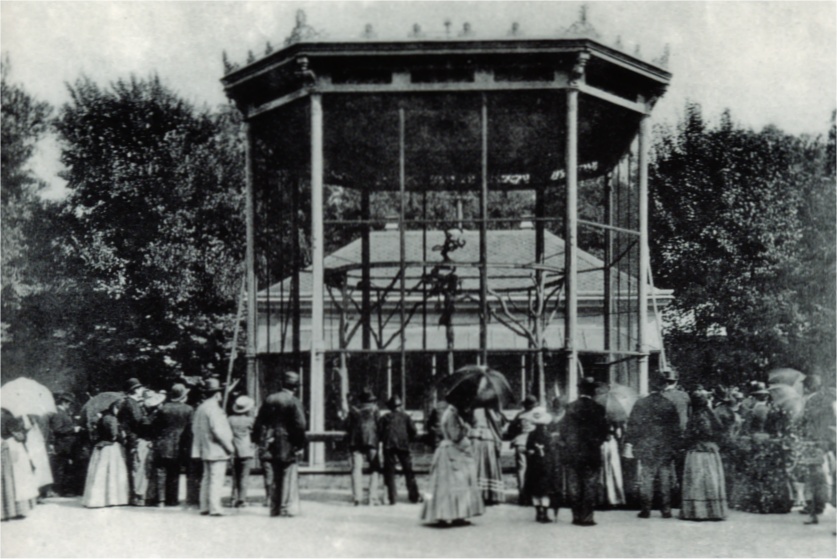

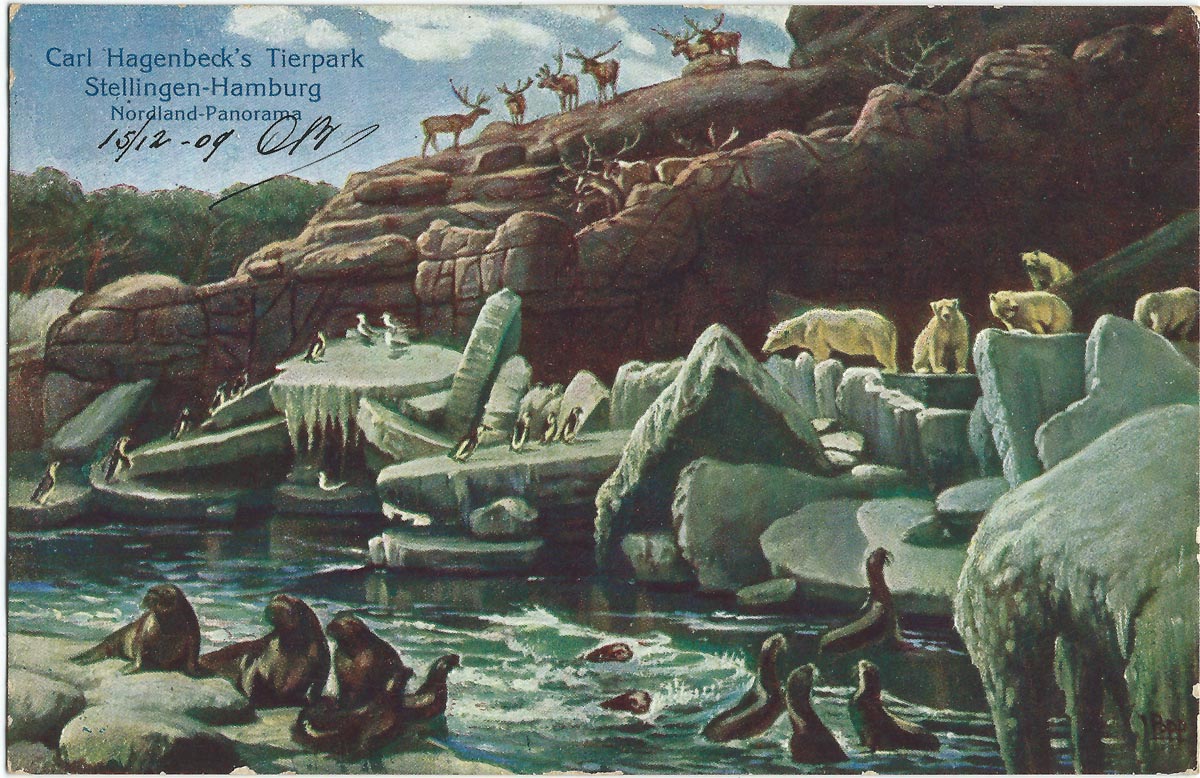

Yet near the close of the nineteenth century, as zoos took on an environmental mission, a new, less-containing, and seemingly more naturalistic type of enclosure arrived at the zoological park. This type of enclosure had no bars—at least no visible ones. In the 1890s, German entrepreneur and Hamburg zoo owner Carl Hagenbeck prompted a shift to “naturalistic” enclosures with the creation of the Panorama.

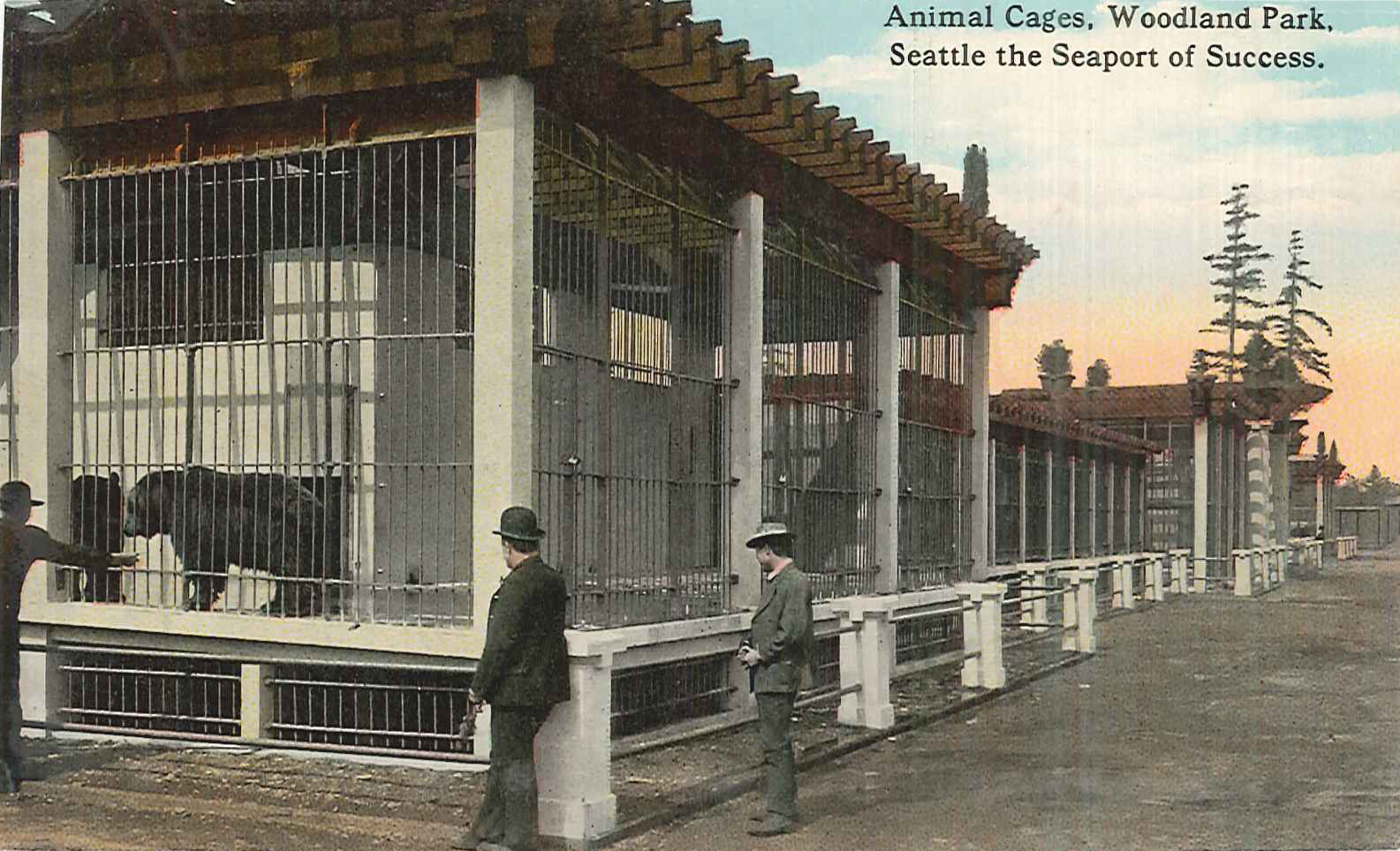

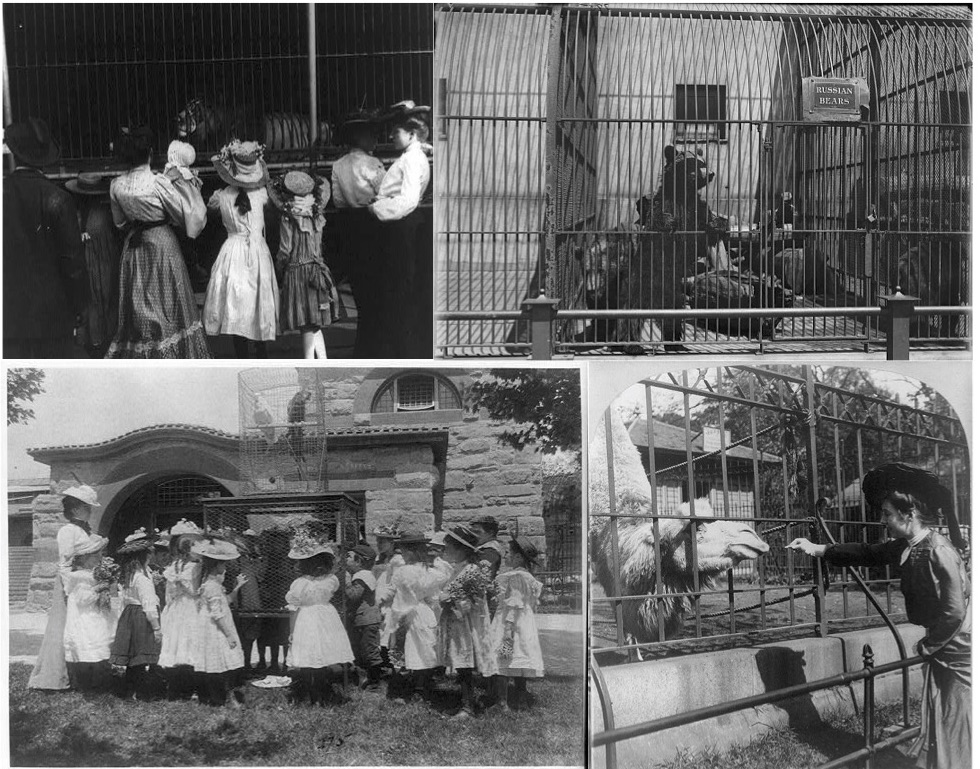

A lion caged in New York’s Central Park Zoo around 1900 (top left). Bears labeled as Russian in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s Highland Park Zoo around 1900 (top right). Schoolchildren gathered around a birdcage at the National Zoo in Washington, D.C. in 1899 (bottom left). A woman feeding a camel in the Central Park Zoo (bottom right).

In Panorama exhibits, animals from the same ecosystem were displayed together in what appeared to be a unified enclosure, complete with appropriate plants, painted backdrops, and fake rocks that all modelled a “real” landscape. The exhibition, though, was in fact composed of a series of separate enclosures divided by invisible moats, allowing Hagenbeck to create a display, for example, that appeared as if seals, walruses, reindeer, and polar bears occupied a single habitat.

The Hagenbeck revolution marked the first attempt by zoos to create naturalistic enclosures that gave visitors the illusion of observing animals in the wild. After Hagenbeck popularized enclosures that modeled environments, zoogoers could imagine animals in their natural worlds instead of simply gazing at animal objects paraded outside of these worlds.

Not all “naturalistic enclosures” were designed like Panoramas. Others, more simply, replaced cages with larger enclosures made to look like fields or forests. As the twentieth century progressed, zoogoers increasingly desired to see animals in settings that appeared to be “wild.”

Constructing these naturalistic environments for zoo animals proved challenging. Just because a zoo desired to place a bison, polar bear, or mountain goat in an enclosure that provided grasslands, polar waters, or rocky precipices, respectively, did not mean that this desire always led to successful outcomes. Zoos forged exhibits through trial and error, continuously learning what animals needed to survive captivity.

These exhibits also required visitors to suspend their disbelief. Clearly, no single spot on earth could simultaneously possess natural arctic, desert, marine, forest, savannah, steppe, mountain, and swamp environments. No matter how healthy and happy their inhabitants remained (and frequently they were sick and miserable), zoo enclosures and their environments remained artificial.

The shift to naturalistic enclosures increased the size of zoo enclosures, and thus did improve the conditions in which animals were held captive. Nonetheless, these enclosures were (and are) anything but natural.

Throughout the last quarter of the twentieth century, “landscape immersion” enclosures became popular within zoological parks. Through landscape immersion, zoo exhibits sought to achieve an even more faithful re-creation of an animal’s natural habitat and then extend this habitat into the area viewers occupied. Rather than display and “overexpose,” in the words of one zoo critic, animals as individual specimens, these exhibits sought to teach zoogoers about the interdependence of animals, plants, and places.

These enclosures sought to teach zoogoers to think ecologically. First developed through the gorilla and African savanna enclosures of Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo in the 1970s, a landscape-immersion exhibit attempted to give an accurate portrayal of an animal’s environment and then transport zoogoers into that environment.

The Visitors

For much of its history, the zoological park was a place of violence. Locked in cages, trapped in enclosures, held in aviaries, and contained in aquariums, animals (when they could not attack or run away) could do nothing but endure the behavior of zoogoers.

Zoos were places where humans could take advantage of captive beasts. Visitors poked at zoo animals with parasols and canes. They spat tobacco juice at them. They fed them, poisoned them, and handed them cigars. In 1895, for example, a man unintentionally poisoned a Diana monkey in the National Zoological Park of Washington, D.C., when he handed it a laurel sprig (deadly to primates) as an incentive to continue the “funny antics” that were entertaining his son.

Zoogoers tossed lit matches and rocks into cages. They jeered, mocked, whistled, mimicked, and laughed at the zoo’s captives. For most, zoo animals were mere objects of entertainment. Exerting violence toward lions, tigers, and bears gave visitors a sense of their own power and mastery over the animal kingdom.

Not all zoogoers, though, were (or are) so cruel. Surely, those who actively taunted animals remained in the minority. Most who strolled through zoological parks did so harmlessly, as one might breeze through the pages of a magazine or cycle through pages on Facebook. For the majority of zoo-goers, animals remained ironically in the background of the experience.

|

| Officials at the zoo in Sydney, Australia allowed famed director Alfred Hitchcock to ride a turtle in 1960. |

In this sense, the zoo was also a place to display one’s class, one’s leisure time, one’s cultural refinement, one’s mobility, one’s sensibility toward Nature, one’s dating rituals, and one’s engagement as a parent in front of other human animals. The zoological park was, for most, a public stage. While a deviant minority enacted violence upon zoo animals, the majority simply paid them little mind. They were busy pursuing other social agendas in the zoo. The story of the zoo, then, is both a story of tragedy and apathy.

Yet, the story of the zoo is also one of transcendence. A small minority of visitors did pass through its entrance gate armed only with curiosity. Upon entering the zoo, many saw the world’s exotic species for the first time. And they learned to take animals seriously as they interacted with them along zoo walkways.

They read the educational placards and zoo guidebooks that provided information about the natural history, systematics, biology, ethology, and ecology of animals as diverse as hyenas, Java porcupines, and prairie dogs. They listened to the lectures that often took place on zoo grounds—like “Cats Ancient and Recent—their Place in Nature, Science and Art,” or “Protozoa; or, the Lowest Forms of Animal Life,” both delivered by famous biologists in the Philadelphia Zoo in the winter of 1877.

Children excitedly look at bears through iron bars at Washington, D.C.’s National Zoo in the 1950s.

They studied the animals, asking questions about them. What do they eat? Why do they grow antlers, have tails, or stay awake at night? Do they have personalities? Predilections? Language? Cultures? Souls? Yet, more significantly, this small minority of zoogoers listened to what animals had to say.

The Encounter

Like the history of any institution, the history of the zoological park is complex. Not only does each zoo have its own story, but each zoo houses hundreds of histories. Every exhibit, every enclosure, and every life enclosed in the zoological park possesses its own unique biography, stretching back centuries or millennia. To stroll through a zoological park is to stroll upon the pages of a deep multispecies story.

Though zoos are places of captivity, they are also places of encounter. Of course, these zoo encounters never happen on common grounds or middle grounds. On zoo grounds, as symbolized by the very idea of enclosure itself, human-animal encounters are always controlled and contained.

Yet, these encounters—as evidenced by the recent controversies about Marius and Harambe— also always move beyond the walls of confinement. Zoo animals always run away, literally and figuratively. Zoo animals always act in unpredictable ways. They always make demands of their onlookers. But few zoogoers pay attention. Few zoogoers listen. And few respond. As is too often the case, in most encounters, power deafens.

Yet the history of zoogoing points us toward future possibilities. How might a zoogoer attempt to walk through, rather than upon, the hundreds of stories woven into the zoological park? I’d like to conclude by offering up a new ethic of zoogoing, a new map to hold while navigating your zoo.

Next time you stand before an enclosure—a bear den, elephant house, seal pond, monkey island, or aquarium—and exchange glances with one of its inhabitants, ask yourself:

1. Who is this individual and why is she here? Was she born and bred in this zoo? Was she acquired from a human institution—a circus, another zoo, a refuge, a wild animal dealer, etc.? Was she rescued? Was she captured? Is she here temporarily? What larger forces place this animal here? What is her story?

2. To what species does she belong? What are her species’ characteristics? Life spans? Behaviors? Diets? Habitats? Mating rituals? Reproductive needs? Communications and languages? Movements? Biogeographies (distribution over geographic space)? Predators? And in what ways does captivity alter these, especially over time?

|

| Even after “naturalistic enclosures” became popular, animals were still literally paraded for visitors, such as in this penguin parade in Edinburgh’s Zoo in 1989. |

3. Where is she? How is her enclosure designed? Note every structure and item in the enclosure. What does the enclosure provide? What does it not provide? What other living beings does she cohabitate with—plants, animals, microbes? How does she respond to each of these? How does she move about her space? How has this enclosure been shaped, or not, by history?

4. Where would she be? What would her environment look like in the wild? What would her ecological relations look like? How would this individual impact the lives of other animals and plants? How would this animal shape its physical landscape? And vice versa?

5. What does this individual’s species mean to us? How have Homo sapiens interacted with this species over time? How have humans changed this species? How has this species changed humans? Why is this species in this zoo? How has this species evolved and changed outside of, or before, human presence?

6. What does this individual symbolize? Humans have always projected their beliefs, values, and ideas onto animals, transforming them into symbols. In fact, all animals possess many (often contradictory) symbolisms at any given moment in time. When you look upon this animal, what comes to mind? What stereotypes do you have? What feelings? What ideas? What does she mean in your culture? What might she mean to other cultures? And why?

The simplest of answers to these questions are complex, lying at the intersection of biology, ecology, ethology, zoology, and history. They require creative and critical thinking. Many of the answers may prove elusive, wild. Yet it is the questions themselves that serve as cornerstones of a new zoogoing ethic.

Next time you find yourself before the countenance of a zoo inhabitant, I challenge you to have a more unsettling type of encounter. Use these questions as a guide to the zoo, and see where they might take you.

Listen to Origins for more on Zoos: Caged: Humans and Animals at the Zoo.

Acampora, Ralph, ed. Metamorphoses of the Zoo: Animal Encounter After Noah. Plymouth, United Kingdom: Lexington Books, 2010.

Baratay, Eric and Elisabeth Hardouin-Fugier. Zoo: A History of Zoological Gardens in the West. London: Reaktion, 2002.

Bender, Dan. The Animal Game: Searching for Wildness at the American Zoo. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016.

Braverman, Irus. Zooland: The Institution of Captivity. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2012.

Donahue, Jesse and Erik Trump, eds. The Politics of Zoos: Exotic Animals and Their Protectors. Dekalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press, 2006.

Friese, Carrie. Cloning Wild Life: Zoos, Captivity, and the Future of Endangered Animals. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

Hancocks, David. A Different Nature: The Paradoxical World of Zoos and Their Uncertain Future. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

Hanson, Elizabeth. Animal Attractions: Nature on Display in American Zoos. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Hoage, Robert J. and William A. Deiss, editors. New Worlds, New Animals: From Menagerie to Zoological Park in the Nineteenth Century.Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

Ito, Takashi. London Zoo and the Victorians, 1828-1859. Suffolk, United Kingdom: Boydell & Brewer, 2014.

Kisling, Vernon N., Jr. Zoo and Aquarium History: Ancient Animal Collections to Zoological Gardens. New York: CRC Press, 2001.

Lee, Keekok. Zoos: A Philosophical Tour. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006.

Malamud, Randy. Reading Zoos: Representations of Animals in Captivity. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

Miller, Ian Jared. The Nature of the Beasts: Empire and Exhibition at the Tokyo Imperial Zoo. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013.

Nyhart, Lynn K. Modern Nature: The Rise of the Biological Perspective in Germany. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Ritvo, Harriet. The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Rothfels, Nigel. Savages and Beasts: The Birth of the Modern Zoo. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002.

Vandersommers, Daniel. “Animal Activism and the Zoo-Networked Nation.” Humanimalia: A Journal of Human/Animal Interface Studies 6, no.2 (Spring 2015): https://humanimalia.org/article/view/9914