Epidemics figure prominently in what we call “Early” American history—a past often animated by the meeting between Africans, Native Americans, and Europeans in the Americas. The idea that diseases such as smallpox, measles, typhus, and influenza decimated Indigenous communities in the Americas is a commonly held one. Like so much of our popular conceptions of Early American history, however, this simple narrative obscures a great deal.

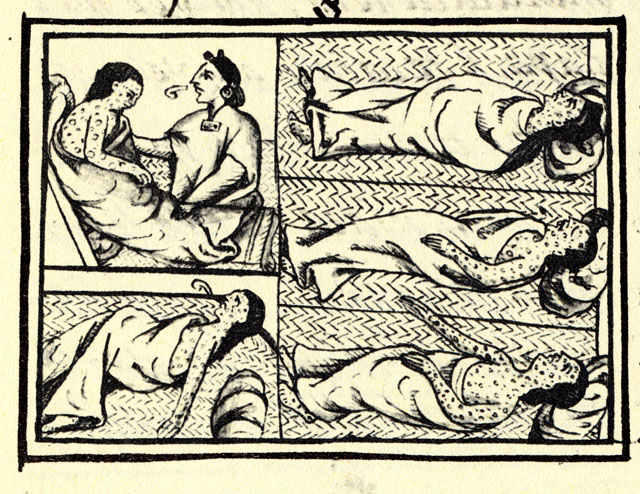

There are good reasons why so many of us think that epidemics wiped out the Americas. Aztecs wrote about a smallpox epidemic just before Spaniards came among them: “there spread over the people a great destruction of men. [Pustules] were spread everywhere, on one’s face, on one’s head, on one’s breast, etc. there was indeed perishing, many indeed died of it.”

Epidemic disease is a touchstone of American history because it seems to explain European conquest of the continents. There has been exciting recent work calling into question the why and how of illness in the age of encounters. The basic question is this: Why did epidemic disease seem to affect Native communities in the Americas much more than their African, Asian, and European counterparts?

Alfred Crosby answered in the 1970s, when he coined the phrase “virgin soil epidemics,” or invasive microbes that were part of the Columbian Exchange (another Crosby coin, meaning the transmission of goods, plants, and people in the centuries after Christopher Columbus).

“Virgin soil epidemics,” according to Crosby, “are those in which the populations at risk have had no previous contact with the diseases that strike them and are therefore immunologically almost defenseless.” American communities had not acquired herd immunity to Eurasian pathogens.

Later, Crosby distilled that given catastrophic demographic changes, it was Europeans’ “germs, not these imperialists themselves…that were chiefly responsible for sweeping aside the indigenes” for settlers to take up the land. More popular works, including those by Jared Diamond (Guns, Germs, and Steel) and Charles Mann (1491) brought those ideas to the public, and they appear in textbooks and journalism frequently.

Today, we are living through a novel coronavirus pandemic (SARS CoV-2), which means that we are again experiencing a virgin soil epidemic. Nonetheless, instead of equal effects across the globe, this pathogen is negatively impacting some communities more than others. Unlike the usual narrative of early America, this time we are not assigning racial causes to those disparities, even as we note racial, ethnic, economic, or other differences in the reported data. Indeed, the healthcare disparities and social variables among us mean that some can mobilize better defenses than others.

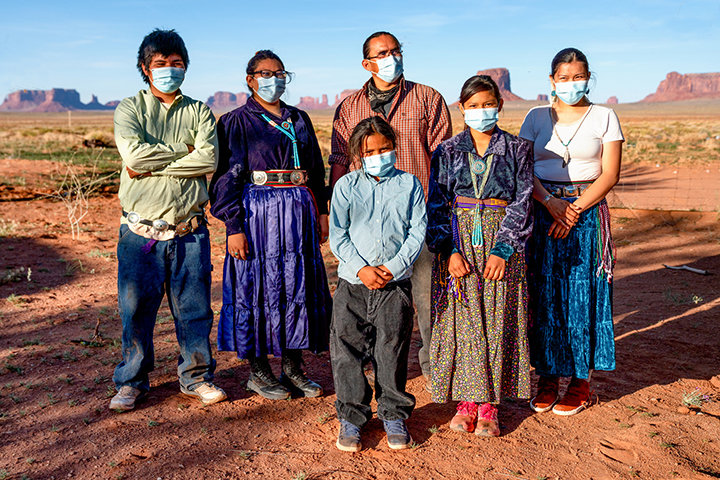

Navajo Nation citizens stand with face masks during the Covid-19 pandemic, 2020.

For example, in Arizona, Native American death rates are nine times higher than for white residents, and in New Mexico, Indigenous mortality is eight-fold the figure for whites. Infamously, those on the Navajo Nation are witnessing a death rate as high, or higher, than the hardest-hit states.

These stark disparities are not because germs affect Indigenous bodies differently. Across the nation, by late May 2020, African Americans were experiencing COVID-19 mortality at a rate 2.4 times higher than whites.

These inequities are not genetic nor due to acquired herd immunity to the virus. They are the consequence of social factors that we ourselves have created.

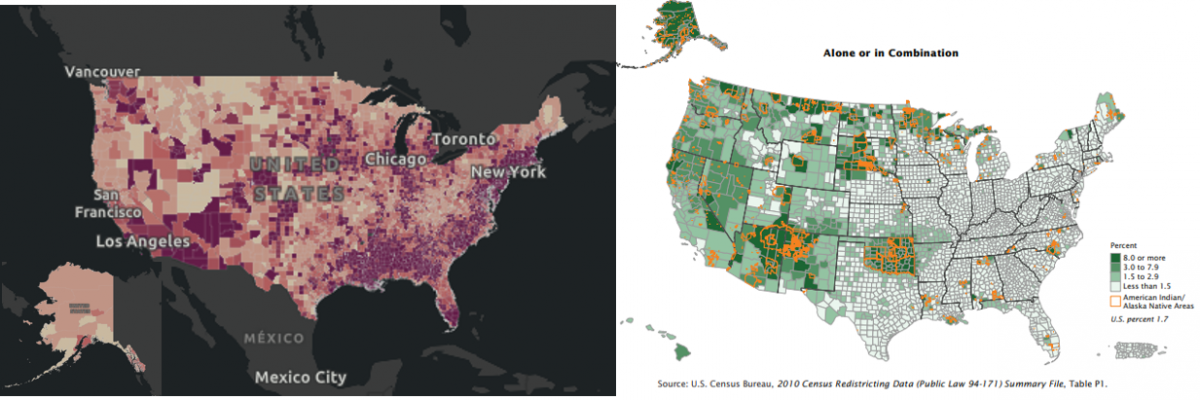

Compare the map of cases of COVID-19 by county (left, from the Johns Hopkins University, which tracks county-level cases and deaths for COVID-19) to the percentage of population of Native Americans and Alaska Natives by county (right, from the 2010 U.S. census map). Although most Native Americans live in urban or suburban areas, some reservation communities are also experiencing a higher rate of COVID-19 than demographics alone would suggest.

Historical examples also complicate our racial presumptions in “virgin soil epidemics.” During the Black Death in medieval Europe, scientists argue that those already experiencing malnourishment or other signs of ill-health were more likely to die.

Union Army soldiers during the American Civil War suffered forty percent mortality from smallpox, and of the further forty percent of soldiers infected with measles, twenty percent succumbed. The Union Army was no “virgin soil” for diseases. In other words, famine and war are not independent of germs.

Rather than rely on the “virgin soil” hypothesis we need to consider the larger social contexts in which disease epidemics happened to fully explain their consequences on particular populations. We should not be so quick to blame germs, or germs alone, for high mortality in Indigenous communities.

For Native Americans, cycles of destabilizing change ricocheted across Indian Country in the era of encounters, which suppressed the overall health of those individuals and their communities. After all, imperialists scorched villages and fields of Native townships; settlers enslaved, bought, or transported Native people across vast distances; they confined Indian communities in inhospitable places; they forced cultural, economic, and social revolutions among Indigenous polities.

Surely these decisions are relevant to the story. Undoubtedly, they increased susceptibilities to contagion—we could call being colonized an “underlying condition” and certainly a “risk factor.” Take a few examples.

The Aztecs themselves tell us how social stresses influenced their epidemic experience in the sixteenth century: “Indeed many people died of them [overcome by pustules], and many just died of hunger. There was death from hunger; there was no one to take care of another; there was no one to attend to another.”

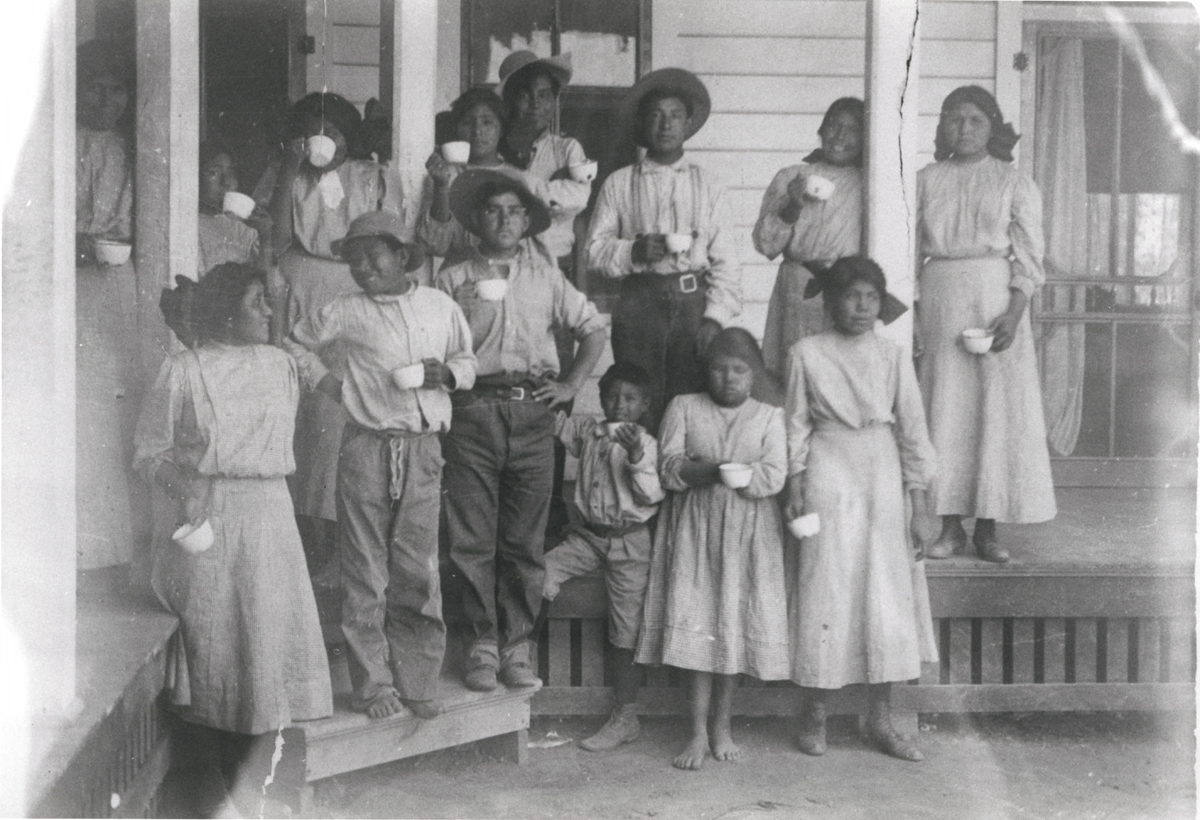

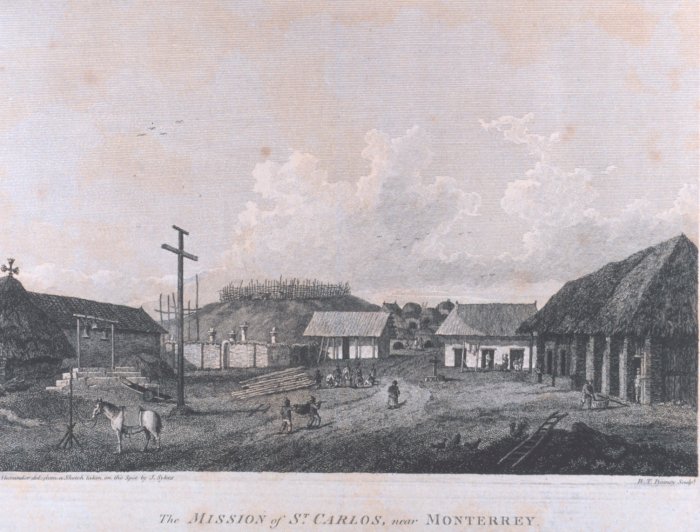

Many epidemics, like that in the Great Lakes in the 1750s, swept in during times of war. In the case of colonial Florida under Spanish missionization, labor and food tribute requirements by Spaniards accompanied the forced relocation of families to more compact ecclesiastical compounds. The result? Skeletal remains show that diets became less diverse (individuals now ate more corn and less meat), which caused distress such as decreased oral health, coinciding with an increase in contagious diseases.

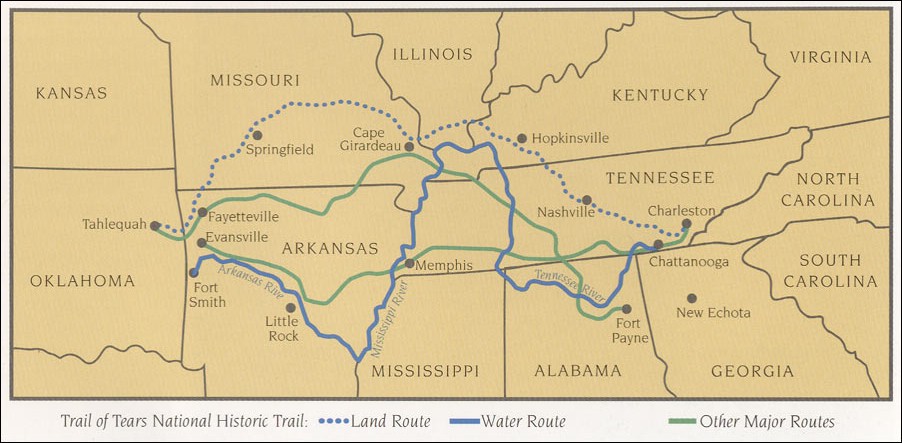

On the Trail of Tears in 1838, Cherokees endured a 25% mortality rate as fevers and dysentery stalked the camps in which they were held before the walk, and further pestilences interacted with malnutrition, exposure, and physical depletion. “There was much sickness among the emigrants,” Rebecca Neugin recalled based on testimony, “and a great many little children died of whooping cough.”

1830s Cherokee communities were not “virgins” to Eurasian diseases; they had three centuries of contact with Eurasian disease vectors and pathogens. It does not require a microscope to see how colonialism—and social realities created by human decisions—affected epidemics in our shared past.

A map of different routes of the Trail of Tears (the forced relocation of Cherokees in the 1830s).

The old tale tells us that germ = death. But germs alone cannot explain the dispossession of continents from their Native owners. To understand that story, we must put germs in their historical and social contexts.

And in the age of COVID-19, it is no wonder that the survivors of those earlier epidemics, who continue to live under colonial rule in cities, on reservations, and everywhere in between, are fighting for the wellbeing of their communities and families.

Want to Learn More?

Catherine M. Cameron, Paul Kelton, and Alan C. Swedlund, eds., Beyond Germs: Native Depopulation in North America (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2016).

Stephanie Russo Carroll, Desi Rodriguez-Lonebear, Randall Akee, Annita Lucchesi, and Jennifer Rai Richards, “Indigenous Data in the Covid-19 Pandemic: Straddling Erasure, Terrorism, and Sovereignty.” Social Science Research Council, Items from the Social Sciences, June 11, 2020. https://items.ssrc.org/covid-19-and-the-social-sciences/disaster-studies/indigenous-data-in-the-covid-19-pandemic-straddling-erasure-terrorism-and-sovereignty/

Nina Lakhani, “Why Native Americans took Covid-19 seriously: ‘It’s our reality.’” The Guardian. May 26, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2020/may/26/native-americans-coronavirus-impact?CMP=oth_b-aplnews_d-1

Jeffrey Ostler, “Disease has Never Been Just Disease for Native Americans.” The Atlantic. April 29, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/04/disease-has-never-been-just-disease-native-americans/610852/

Darius Tahir and Adam Cancryn, “American Indian tribes thwarted in efforts to get coronavirus data.” Politico. June 11, 2020. https://www.politico.com/news/2020/06/11/native-american-coronavirus-data-314527