Coming to terms with the American Civil War is no easy task. The scale of its destruction alone is still shocking. New historical estimates put the death toll at 750,000 soldiers, or 2.4% of the American population in 1860, which would translate today into a death toll of 7.5 million Americans. This demographic impact says nothing, though, about many of the war's other legacies, including a transformed federal government, a shift away from an agricultural slave-labor economy towards industrial capitalism, a lasting debate over state sovereignty, unresolved regional rivalries, and enduring questions of race and citizenship.

James McPherson, the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian of the Civil War, has compiled a dozen of his essays into this short and engaging volume. Those readers unfamiliar with the history of the conflict can expect to learn much of the war's military, diplomatic, political, and social history, even as McPherson's sharp prose and narrative style keep the writing brisk.

One question that the volume presents is how the period of armed conflict from 1861-1865 might be considered part of a much longer war that, albeit primarily ideological, saw its fair share of violence. With one chapter exploring the role of the 1846-1848 Mexican War in the South's eventual secession and another examining the continuing paramilitary and terrorist violence in the South after the Civil War, 1861-1865 seems narrow indeed.

McPherson also engages many of the war's military dimensions, including the role of naval conflicts in opening up the possibility of foreign intervention and the question of whether the Civil War was a "just" war and a "total" war. Other chapters reflect on President Lincoln and emancipation, asking how his stance on slavery evolved over the course of the war, how his decision to abolish slavery moved from military strategy to national policy, and whether it was more his decision or slaves' own agency that resulted in their eventual liberation.

McPherson argues that U.S. territorial expansion as a result of the Mexican-American War intensified many of the debates about slavery that would only come to a head more than a decade later with Southern secession. The fight over whether the land wrested from Mexico would be open or closed to slavery triggered a realignment of political affiliations, "mark[ing] an ominous wrenching of the party division between Whigs and Democrats into a sectional division between free and slave states that foreshadowed the political breakdown."

When gold was discovered in California, tens of thousands of people poured in by spring of 1849 and, to avoid the competition of slave labor, it entered the union as a free state the following year. "The balance of power permanently tipped against the South," McPherson writes, "which strengthened the influence of those who clamored for disunion." Showing how California's story both shaped and anticipated the sectional conflict that would later erupt in war, McPherson reminds readers of the broader temporal and spatial context out of which the Civil War ultimately grew.

When war finally came, was it a just war? Was it a total war? A key element of both definitions is the preservation, or lack thereof, of a distinction between combatants and non-combatants: a just war maintains the separation while a total war erases it. McPherson argues that the conflict became increasingly unjust and, although never quite total in the way that twentieth-century conflicts would be, it was certainly not marked by restraint. As the conflict wore on, the distinctions between enemy soldiers and civilians blurred, as non-combatants increasingly became both contributors and victims.

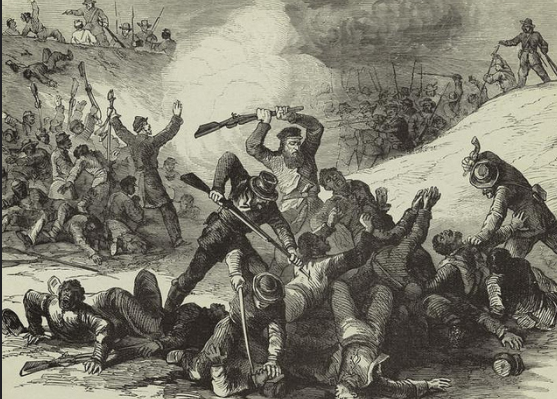

For example, Southern civilians' irregular warfare behind Union lines frequently supplemented the Confederates' conventional forces, guerilla warfare in Missouri pitted neighbor against neighbor, and Southern troops occasionally murdered captured black soldiers serving with the Union. McPherson argues, however, that there were never intentional, systematic efforts to kill enemy civilians or prisoners of war and Union policy only aimed to destroy those resources that supported the Confederate war effort.

Later chapters reflect on the nature of slaves' emancipation and the role of Abraham Lincoln in it. One line of argument holds that by "coming into Union military lines in the South, [slaves] forced the issue of emancipation on the administration." Although McPherson gives much credit to their agency, he also points out that the primary mechanism of liberation for most slaves remained the 13th Amendment. Lincoln no doubt deserves credit, then, even if his stance on slavery had not always been as enlightened as it was by war's end. His antislavery convictions actually began as "gradualist and colonizationist" (the latter referring to a plan to help freed slaves emigrate out of the U.S.) and only evolved slowly over the course of the war.

In reestablishing the military context of the war's most important social measure, McPherson argues that the Emancipation Proclamation began as a military strategy to weaken the Confederacy and only later became a national policy. "To win a war over an enemy fighting for and sustained by slavery," he states, it was necessary for the North to "strike at slavery."

The final chapter turns to postwar reconstruction in the South, which McPherson argues was "a continuation of war by other (but distressingly similar) means." Freedpeople, for example, became second-class citizens under new southern governments' "Black Codes" and faced terror and violence at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan and other paramilitary groups composed of Confederate veterans (eventually organized as "social clubs" to avoid federal retaliation). When Republican governments in the South finally collapsed and President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew all federal troops in 1877, the white "redemption" of the South was complete. So began a nominal peace, "marked by disenfranchisement, Jim Crow, poverty, and lynching."

McPherson's final pages leave two lingering questions: who really won the Civil War and when did it finally end? Readers familiar with current debates over Confederate War monuments, the status of American citizenship, state sovereignty, white supremacist groups, and lasting racial inequalities will recognize that these questions bear not only on the past, but also on our present and future.