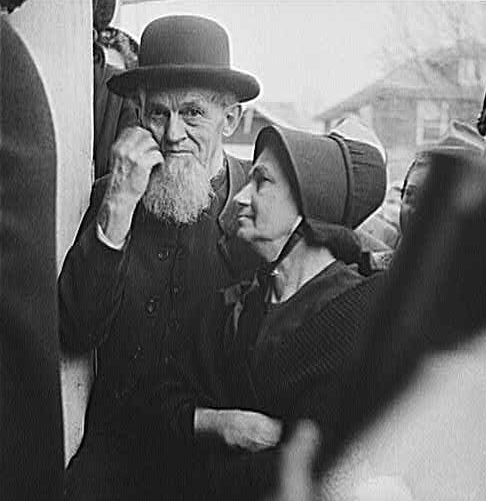

In 1942, when this photograph of an elderly Mennonite couple was shot in Pennsylvania, science and medicine were transforming the idea of old age by extending life expectancies and curing chronic disease. Most Americans at this time supported some form of national health insurance, but only particular groups such as the aged would soon receive it. Photo by U.S. government photographer Marjory Collins.

Baby boomers, 78 million strong, are turning 65 at a rate of 4 million per year. The press, the government, and the medical community claim, often and loudly, that these numbers augur a mass dependency crisis. Such spokesmen envision a world of decrepit elders afflicted with chronic disease slurping their way through the country’s resources. This month historian Tamara Mann explores how, in the United States, the so-called “geriatric crisis” is less related to age itself than to the relationship between old age and government funds, particularly Medicare. She explains how 65 became a federal marker of old age and why health insurance came to be offered as the best solution to the problems afflicting America’s elders.

Read more on American social policy: The History of U.S. Health Care Reform (PDF File); Unemployment; Immigration Policy; Higher Education; and “Class Warfare” in American Politics.

Baby boomers, 78 million strong, are turning 65 at a rate of 4 million per year in the United States.

The press, the government, and the medical community claim, often and loudly, that these numbers augur a mass dependency crisis. Such spokesmen envision a world of decrepit elders afflicted with chronic disease devouring the country’s resources.

Still, amidst the alarmists, a few commentators acknowledge that aging itself has changed. Many boomers are working well into their 70s and 80s, staying in remarkably good health, and reinventing this final stage of life. In short, they are proving that chronological age is not biologically uniform.

In the United States the so-called “geriatric crisis” is less related to age itself than to the relationship between old age and government support—such as the unequal distribution of health care dollars, via Medicare, across the age spectrum.

Such policies assume that people over 65 are by definition in worse health, dependent, and in need of government support. Yet this is not always the case. A financially independent, healthy 70-year-old costs society less than an ill 40-year-old.

Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, Americans argued over the proper relationship between the state and its elderly citizens. They tried to define “old age” and its problems, while questioning the federal government’s obligation to offer a solution.

In different measures, the Social Security Act in 1935 and the passage of Medicare in 1965 offered policy conclusions to these debates. The elderly would be defined as individuals over 65 years of age and the problem of old age would be characterized as illness and its related expenses.

Neither of these conclusions was foregone; both were expedient answers to social and political pressures. Indeed, many analysts over the century did not believe that old age necessarily meant ill health or dependency if approached correctly. They opposed plans and policies to separate the elderly from the rest of the population, and advocated for preventative health spending throughout the lifespan.

This article will return to the middle of the twentieth century to explore how 65 became a federal marker of old age and why health insurance came to be seen, in the years following the first National Conference on Aging (1950), as the best solution to the problems afflicting America’s elders.

The “Problem” of Old Age

On July 30, 1965, Lyndon Johnson, the 57-year-old President of the United States, honored 81-year-old former president Harry Truman by traveling to Independence, Missouri, to sign into law a bill that would give America’s elders federally funded health insurance.

The passage of Medicare—a policy that Truman had reluctantly supported in the early 1950s—became Johnson’s political windfall. Johnson could now claim to have solved the “problem of old age.”

The problem of old age started to attract public and political attention in the 1930s, when industrialization, urbanization, mass unemployment, and the Depression combined to leave many of the aged without jobs or support from their extended families.

As a result, during this decade, the problem of old age was largely characterized as impoverishment due to unemployment.

At the same time, the elderly were a group whose numbers were on the rise. Advances in public health had transformed life expectancy in America: from 1860 to 1930 the percentage of the American population over 65 had more than doubled. In ten years, from 1930 to 1940, there would be an additional 36.5 percent increase in this group, at a time when the entire population increased by only 7.2 percent.

Within the decade, spokesmen across the United States pressed the government to enact more pension programs. By the time Franklin Roosevelt became president, some thirty states delivered pension programs, albeit unevenly; only 3% of those deemed aged were receiving state funds in 1935.

The fight for pensions, or just cash, continued through the thirties in the popular Townsend Old Age Revolving Pension Plan, Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California (EPIC) plan, and Robert Noble’s Ham & Eggs movement. All of these groups argued that the government should give a stipend to those deemed too old to work, whether 50, 60, or 65.

At its base, the philosophy of social insurance, or the social welfare tradition, maintained that governments should provide some measure of economic security. First enacted in 1889 by Otto Von Bismarck in Germany, social insurance programs spread quickly across Europe.

American yearnings for such programs emerged with Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 and reached an apex during the Great Depression. In 1927, Abraham Epstein, a weathered state pension advocate, announced: “It’s time for a group that will do nothing but work to create old-age pensions.”

Mindful of the sullied public reputation of the word pension, Epstein titled his organization the American Association for Old Age Security, later to be renamed the American Association for Social Security.

Epstein’s rechristening worked. Quickly backed by such activist luminaries as Jane Addams and Florence Kelley, Epstein and his intellectual mentor, I.M. Rubinow, helped create a federal social security program. Ad campaigns exposing the horrors of the poorhouse bolstered the numbers of Epstein’s supporters and focused further attention on the plight of unemployed elders.

By 1934, Epstein had succeeded in nurturing American empathy for the aged if not for his particular pension plan. In his proposal, the unemployed would receive money from a central pool funded by employee and employer alike. Conservatives skewered him and his supporters for advocating a redistributive scheme that reeked of communism.

In 1934, President Roosevelt issued an executive order to create the Committee on Economic Security with the goal of studying and solving the problem of economic insecurity in America. Epstein along with other social insurance experts advocating redistributive programs were strategically left out of almost every planning meeting.

Still, asserts historian Michael Katz, through Epstein and his cronies, “old-age security broke loose from its earlier association with poor-relief; forged ahead of every other kind of social insurance; and earned its privileged place as the only irreversible and untouchable welfare program in American history.”

On August 14th, 1935, President Roosevelt signed into law the monumental Social Security Act. The Act failed, Epstein protested, to redistribute wealth or actually alleviate economic insecurity for the most needy (since it offered relatively equivalent support to all older Americans). Nonetheless, it fundamentally changed the relationship between the government and its older citizens, setting apart the elderly as a distinct social and political group that the government now took responsibility to assist and protect.

How 65 came to be “Old”

In 1935, the aged—or “oldsters,” as they were often called—were not exclusively defined chronologically. In fact, numerous doctors and scientists working in the 1930s pushed for a biological, rather than chronological definition of old age, claiming that physical markers and not simply the passing of years best defined old age.

They looked at the correlations between poverty, chronic disease, family history, and psychology to determine that the onset of senescence or old age was relative rather than uniform. These early gerontologists believed that employment and usefulness would stave off the markers of old age. Still, they had little control over industry policies that pushed workers out of jobs at the early age of 40. Some factories even retired women at 35.

The Committee on Economic Security understood both the harsh economic reality of forced retirement and the absolute social necessity to keep the young employed. The Committee settled on 65 as the marker of old age for its economic feasibility.

At the time, life expectancy at birth was 58. Taking their cues from existing state pension systems and the recently passed Railroad Retirement System, the committee recognized that 65 was a number that could be sustainably financed through payroll taxation.

As historian Andrew Achenbaum reports, “As a result of the Social Security Act, old age—defined for administrative purposes as the attainment of age sixty-five—for the first time became a criterion for participation in several important programs at the federal level.”

From 1935 on, the U.S. federal government committed itself to the well-being of its senior citizens, who hereby would be defined as individuals over 65 years of age.

Wards of a Biomedical State

By the 1940s, the pension movement of the 1920s and 1930s had largely collapsed. Having achieved the Social Security Act, popular participation in pension-oriented lobbying groups diminished and political organizers focused attention elsewhere. Then, just as the pension movement slowed to a halt, the field of biomedical research exploded.

Science and war proved productive partners. The utilization of penicillin, skin grafts, and blood transfusions, writes historian Victoria Harden, “enhanced public belief that scientific research offered an endless frontier on which a happier, healthier life could be built.”

After the War, Congress went to work, sponsoring a spate of legislation to update American health care. According to Medicare expert Theodore Marmor, federal spending after WWII focused on three areas, “medical research, hospital construction, and federal health insurance programs.”

While scientists and doctors in the 1930s sought to ameliorate the social and physical stigmas of old age by discovering the parameters of what healthy aging could look like, scientists and doctors of the forties and fifties came to believe that chronic diseases could be reversed in laboratories and cured in hospitals. The federal government agreed.

While the federal government got into the bio-medical business, older Americans, reeling from the unintended consequences of the Social Security Act—such as forced retirement whether a person could or wanted to work longer—joined together in community halls and religious institutions to figure out where they stood in the post-war order.

“By setting an arbitrary retirement age,” the co-authors of The Senior Rights Movement argue, “the Social Security Act had inadvertently circumscribed the problems of persons over 65 as a distinct set of social problems. As such it provided a coherent basis for their solidarity and common identity and gave a newfound sense of legitimacy to elderly demands for social justice.”

In 1950, this nascent group of politically conscious elderly collided with an energized bio-medical industry and fair-deal policy wonks at the Federal Security Agency (FSA)’s National Conference on Aging.

Old Age Insurance and the First National Conference on Aging

In 1949 Oscar Ewing had problems. Since taking over the Federal Security Agency (FSA) in 1947 he had become a maligned figure in Washington. Branded by the American Medical Association as “Mr. Socialized Medicine,” Ewing opened his political life with a more modest nickname, Jack.

The straight-laced technocrat started his career in high school as the secretary of the Decatur County, Indiana, Democratic Committee, and pursued his political ambition at Indiana University, becoming first president of his junior and senior classes and then valedictorian. From there, he went to Harvard Law School, edited the Harvard Law Review, and eventually started his own law firm in Indianapolis. After enlisting as a first lieutenant in World War I, Ewing returned as a captain, primed to take on high profile legal cases and enter national politics.

In 1944, he publicly supported Truman’s run for the vice presidency, thereby securing a position as one of Truman’s key political strategists. When Truman became President, he urged Ewing to head the FSA and help him pass national health insurance.

In 1942, Fortune magazine announced the American public’s support for national health insurance (PDF File) as a whopping 74%. It seemed just a matter of time until the United States followed in Europe’s path and offered every citizen the right of health care.

In 1944, President Roosevelt called for an “Economic Bill of Rights” proclaiming that every American had the “right to adequate medical care . . .” With Roosevelt’s untimely death, Harry Truman took up the mantle and tried unsuccessfully to push national health insurance through the clenched jaws of the Republican Congress.

The President’s tepid approval ratings, the postwar Congress’s conservative bent, and the powerful alliance of anti-national health insurance special interest groups, spearheaded by the American Medical Association (AMA), combined to thwart health insurance legislation from 1945 to 1947.

Ewing became the much-maligned face of Truman’s thwarted National Health Insurance program. In a profile titled “Ewing: Deeply Sincere Man or Designing Politician?” The Sun attempted to get a handle on the vitriol. Was Oscar Ewing, “a quiet, mild-mannered, deeply sincere man who left a lucrative law career to serve his country,” or a “skillful, designing, power-thirsty politician bent on fastening the ‘welfare state’ tighter and tighter upon the American people…”? Ewing, The Sun would agree, desperately needed a break.

At a cocktail party in 1949, the famed publisher William Randolph Hearst Jr. gave him one. Hearst, Ewing recalls, leaned in and said, “I’m very much in favor of your idea for national health insurance. But the thing that worries me about it is that if anything went wrong, if it didn’t work, the upheaval that would result would be catastrophic because we would have a completely different system of medicine….Isn’t there some small segment of the problem that you could pick out, apply your health insurance program to it, use it as a pilot plan operation?”

Ewing liked the idea, but which segment of the population could quiet the conservative opposition?

Louis Pink, a former client and insurance expert with New York Blue Cross/Blue Shield, suggested covering the elderly, a high-risk group that insurance companies avoided. Ewing understood the value of Pink’s suggestion. The government, he thought, could start slowly, insuring those over 65 and then expanding to other groups.

National health insurance, like the history of voting, would be incremental, bestowed to one group at a time. The brains behind Truman’s social security legislation, Arthur Altmeyer, Wilbur Cohen, and Isadore Falk, were less persuaded. In fact, Ewing recalled, they “were completely wedded to national health insurance and didn’t want to take less.”

Then came the “oldsters.”

In April 1949, the few existing elderly experts assembled at the FSA offices to discuss the mounting demographic problem of unemployed, impoverished, and discarded elders. The problem of old age, these experts claimed, was as much existential as it was physical.

Old age, explained Ollie Randall, one of the few known elder activists working at the time, “is a period of losses—loss of family, of friends, of job, of health, of income, and most important of all, of personal status.” It doesn’t begin at the same time for everyone but when it does, Randall explained, it is the loss of personal status or of social usefulness that elderly men and women described as the most crushing. “To feel useless or unimportant,” she argued, “is the most devastating experience a person can have.”

To put the elderly back to work and salvage their dwindling reputation as employable and capable citizens, the FSA, with Randall’s and others’ urging, decided to host a conference on old age.

The first National Conference on Aging held in 1950 achieved mixed results. Although the Conference established the elderly and their hardships as national issues, replete with federal committees and popular journals, the content goals stated by the conference participants came to be overshadowed.

The lasting results of the First National Conference on Aging would be the demonstration of the growing power of America’s senior citizens and the marriage of this power to Oscar Ewing’s old-age hospital insurance program.

The Aged Matter

“You should live so long,” chirped N. S. Haseltine, in a snarky Washington Post piece. “And because you will,” he continued, “national experts convened here to talk over what should be done for you.”

The day was August 13, 1950; the place was Washington, D.C., where over 5,000 “out of towners” descended on the sweltering city to attend a conference-packed weekend. In addition to the meagerly populated National Conference on Aging, the Army and Navy Union of the U.S.A., the International Typographic Union, the Croatian Fraternal Union of America, and the Pi Phi Fraternity competed for broadcast minutes.

With only 816 people in attendance, the National Conference on Aging, at the stately Shoreham Hotel, still managed to capture the country’s attention. Newspapers from California to New York reported on the massive implications of this recently discovered social problem.

For one thing, the guests were colorful. Dr. Francis E. Townsend arrived prepared to push his latest pension plan, $150 a month for everyone over sixty.

Then came the “Texas cyclone,” an avuncular figure with “the longest name, longest beard, and longest tongue of Texas,” Arlon Barton Cyclone Davis, to advocate for pay-as-you-go pensions and demonstrate his sixty-nine years of impeccable health.

Representatives from General Electric, Eastman Kodak, the Motion Picture Association of America, life insurance companies, hospitals, and social welfare agencies hunkered down for back-to-back sessions on the indignities faced by America’s elders.

For three days, interested parties gathered to confer on the “problem of old age.” Despite a wide range of professional training, and active debate, the participants settled on surprisingly similar conclusions.

Whether they attended the meeting on “Employability and Rehabilitation” or “Living Arrangements,” these new experts claimed that the hardships of old age could be discussed primarily through the language of dependency. The problem of old age, they concluded, was not actually a problem of passing birthdays. Rather, it was part of an intergenerational plight of physical and financial dependence.

The working group on health, the largest at the Conference, came to be one of the most vocal adversaries of age-based policies. In their written summary, the group asserted that the bulk of medical spending must be used for early intervention. Rather than attend to disease at the end of life, they argued that health-care professionals should focus on preparing middle-aged individuals for years of optimal health in their homes.

The emphasis should remain on creating the “well person” rather than coping with the sick one. For this reason, isolating the elderly from other age groups in terms of health care did not make sense. The group concluded, “health programs for the aging should be developed within the framework of our total health services. Further fragmentation would be wasteful and would perpetuate an undesirable social concept.”

Ewing took the Conference’s conclusions seriously. He realized the problems of old age were complex, intergenerational, personal, and societal.

Still, he couldn’t help but view the throngs of politically primed elders through his own policy prism. He saw their voting potential and realized that they would be a new and powerful constituency.

At the start of his duel with the AMA over national health insurance in the late 1940s, Ewing wanted to organize an equally powerful American Patients Association. After August 1950, he realized that the elderly could be that association. The numbers were on his side. “You had 19 million people over 65, and you had 185,000 doctors,” he exclaimed.

After the conference, Cohen and Falk came to Ewing’s side, completing a draft of the legislation by 1951. The duo found a way to make old-age insurance palatable to a resistant Congress.

First, they limited the insurance to hospital expenses, thus following the established path of federal support for hospital growth. Second, they decided to integrate hospital insurance into the newly expanded and nationally respected Old Age and Survivors Insurance program.

By restricting health-care benefits to Social Security recipients over 65 (and their spouses), they avoided a means test, as well as charges that they were giving benefits to the undeserving. In this case, the elderly would have prepaid for their health insurance through taxes over the course of their lives.

To persuade Congress, they began compiling data on the connection between old age and illness as well as deficits in insurance coverage for those over 65. Deployed to offer a simple causal relationship between old age and illness and then illness and poverty, the data ignored the complicated and multi-directional relationship between poverty, unemployment, depression, and disease.

As Wilbur Cohen would later write, “anyway, it’s all been very Hegelian. The state and federal proposals for compulsory health insurance were the thesis, the AMA’s violent opposition was the antithesis, and Medicare is the synthesis.”

In April of 1952, Senators James Murray (D-MT) and Hubert Humphrey (D-MN) and Representatives John Dingell (D-MI) and Emanuel Celler (D-NY) introduced Ewing’s old age hospital insurance bill in Congress. Truman gave Ewing permission to move forward but never truly put his weight behind the program. Neither the Senate nor the House had hearings on the bill. “They couldn’t even get hearings on Medicare, when I had it introduced,” lamented Ewing.

In the fall of 1953, the situation looked bleak. The Truman administration had failed to implement national health insurance and failed to implement restricted hospital insurance. With the end of the Truman administration, remarked Ewing, “also came the end of any real pressures for national health insurance.”

What did not end, remarkably, was the pressure for Medicare.

The Problem of Old Age Becomes the Problem of Illness

As the cost of medical care continued to rise, so did the organizational capacity of the elderly. Local old age groups, religious societies and Golden Ring Clubs began to agitate for help and a new lobbying group, The National Council of Senior Citizens, pushed Congress to enact Ewing’s hospital insurance program.

The definitions and solutions to the problem of old age voiced at the First National Conference on Aging gave way to the language of political expediency.

The problem was no longer dependency, but poverty caused by health failure and rising health-care costs. The AMA now had to battle with an organized front of aged activists, who argued that America’s deserving grandfathers and grandmothers were undeservingly poor because they were ill.

Between 1950 and 1965, the contours of American politics around health policy transformed. The power structures shifted in Congress, interest groups lost and attained influence, and a new American solution captured the hearts of the country.

From 1957 until 1964, bill after ill-fated bill bounced through Congress, until finally, on July 30th, 1965, the conclusion of decades of compromise actually stuck. An amendment to the Social Security Act providing hospital and medical insurance for Americans over 65 years of age became law.

But more than just policy changed.

By the 1960s, the conversation around the problems of old age grew ever more anemic; chronological age came to be an accepted way of dividing the old from the young, and aging became a disease to be solved.

Old age is not a static concept. It is defined, like so many other animating categories, by social assumptions, political necessities, and biological mechanisms.

In the United States, old age has come to mean something chronologically specific with very concrete policy benefits. Sixty-five continues to mark a person as “old.” Yet, this arbitrary number makes increasingly less sense in an age where life expectancy at birth has jumped to a man’s late 70s and a woman’s early 80s.

As 78 million baby boomers turn 65, live decades with degenerative diseases, and prepare for a new kind of retirement, the definitions and lived experiences of old age are undergoing a fundamental transformation.

How policy should follow these changes is a debate worth having.

For more on this topic, read Tamara Mann's article "Dying Well" in the Harvard Divinity Bulletin.

Achenbaum, W. Andrew. Old Age in the New Land: The American Experience Since 1790. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1978.

———. Shades of Gray: Old Age, American Values, and Federal Policies Since 1920, Little, Brown Series on Gerontology. Boston: Little Brown, 1983.

———. Crossing Frontiers: Gerontology Emerges as a Science. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Cole, Thomas R. The Journey of Life: A Cultural History of Aging in America. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Corning, Peter A. The Evolution of Medicare: From Idea to Law, United States. Social Security Administration. Office of Research and Statistics. Research Report; No. 29, Washington: Office of Research and Statistics, 1969.

Fischer, David Hackett. Growing Old in America, The Bland-Lee Lectures. New York: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Fox, Daniel M. Power and Illness: The Failure and Future of American Health Policy. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.

Gratton, Brian. Urban Elders: Family, Work, and Welfare Among Boston's Aged, 1890-1950. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1985.

Haber, Carole; Gratton, Brian. Old Age and the Search for Security: An American Social History, Interdisciplinary Studies in History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Katz, Michael B. In the Shadow of the Poorhouse: A Social History of Welfare in America. New York: Basic Books, 1986.

Kooijman, Jaap. …And the Pursuit of National Health: The Incremental Strategy Toward National Health Insurance in the United States of America, Amsterdam Monographs in American Studies. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1999.

Marmor, Theodore R. The Politics of Medicare. New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 2000.

Pratt, Henry J. The Gray Lobby. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1976.

———. Gray Agendas: Interest Groups and Public Pensions in Canada, Britain, and the United States. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1993.

Quadagno, Jill S. The Transformation of Old Age Security: Class and Politics in the American Welfare State. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.

———. One Nation, Uninsured: Why the U.S. Has No National Health Insurance.Oxford University Press, 2005.