Many Americans, apparently, are really angry at China right now. They believe that China is taking advantage of the United States with unfair trade practices and by manipulating its currency. In fact, American politicians and bankers have been concerned with China's currency for a very long time. This month historian Austin Dean traces this long history of American involvement in China's monetary policies and shows that Americans have been more the manipulator than manipulated.

“China is killing us.”

It is a favorite phrase of Donald Trump, the real estate mogul, turned reality television star, turned Republican nominee and now, President-elect of the United States. Chinese action to keep the value of its currency low, Trump insists, is “robbing Americans of billions of dollars of capital and millions of jobs.”

President Barak Obama and President Xi Jinping toast during a 2014 State Banquet in Beijing, China.

In most recent presidential election cycles, candidates take shots at the People’s Republic of China. Some single out human rights issues, others Chinese foreign policy, but the most common rhetorical barbs tie back to trade and currency.

This is not new.

Since the founding of the United States, merchants, government officials, economists and journalists pondered how to increase trade with the world’s most populous nation to benefit American economic growth. And they have often sought to create closer links between the American and Chinese monetary systems to help foster this trade.

Chinese officials in the 19th and 20th centuries at times resisted these American overtures and at times sought to draw the United States into supporting China’s currency and, in turn, its government.

After the death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and the start of Reform and Opening under Deng Xiaoping in the 1980s, trade between the United States and China increased dramatically. However, by end of the 20th century and into the early 2000s, the fixed exchange rate between the Chinese renminbi (the people’s currency, RMB) and the dollar became a source of tension between the two largest economies in the world as many in the U.S. Congress sought to label China a “currency manipulator.”

The currency question in U.S.-China trade relations has been around for more than 200 years. It will not be going away anytime soon.

The Early American Republic and the Qing dynasty

In 1783, the ship Empress of China left New York harbor and headed to Canton, the sole port open to foreign trade during the Qing dynasty. Founded in 1644, the Qing was the last imperial dynasty in Chinese history but, before its end, it became one of the largest and most prosperous empires in the world whose trade goods—teas, silks, porcelains—became valued all over the world. The newly independent United States wanted a part of this trade.

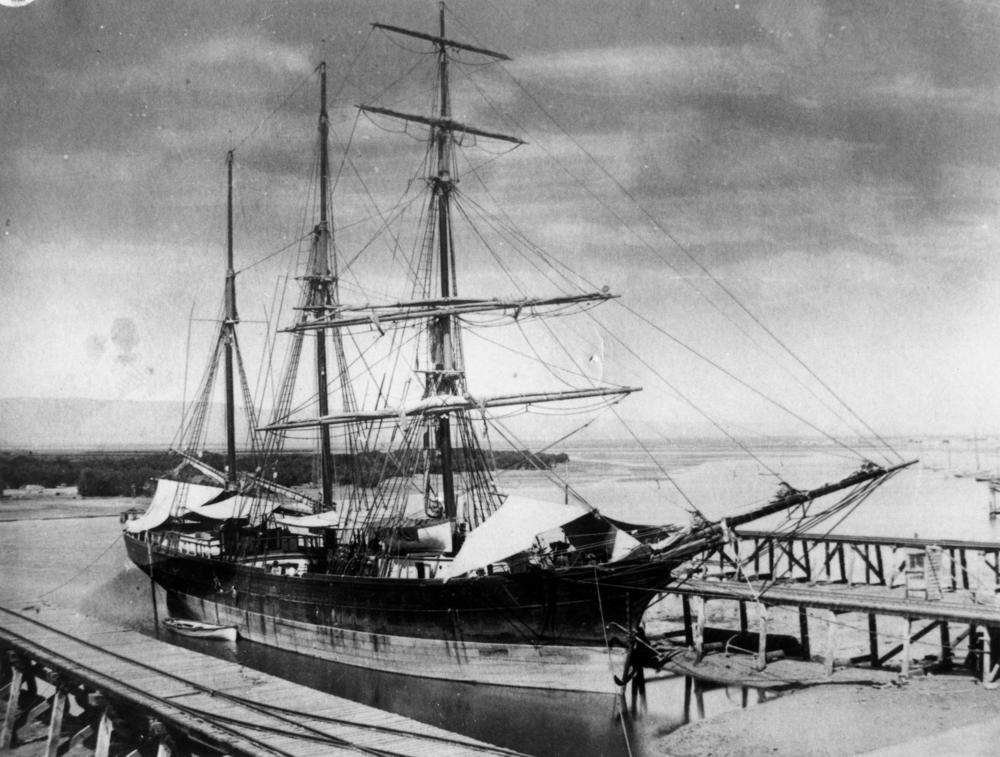

|

| The Empress of China in 1876, nearly 100 years after it left New York harbor for China as the first American merchant vessel to enter Chinese waters. |

Backed by Robert Morris, financier of the American Revolution, the Empress of China departed the newly established United States with furs, ginseng, and other goods to trade in Canton. The ship also had something else in its cargo: more than 20,000 Spanish silver coins. The goods the Americans were bringing would not be enough to procure the products they hoped to buy. The traders had to settle the remaining balance with Spanish silver dollars.

From Mexico City to Manila, Spanish silver dollars flowed through the arteries of global commerce in the 18th and 19th centuries. In the United States, Alexander Hamilton used them as an important reference point for his “Report on the Coinage” that ultimately put the United States on a bimetallic monetary system. In fact, Spanish, and later Mexican, silver dollars were legal tender in the United States through the 1850s.

Silver peso of Philip V of Spain minted in Mexico in 1739 (left). 1888 “Trade Coins” from Mexico with multiple “chop” marks made by Chinese merchants to verify their authenticity (right).

Spanish silver was an important part of the Chinese monetary system. Deposits of the metal in China were not significant, so it came from abroad, first from Japan and then from the Americas. (Copper coins were generally used in local trade while silver was used in interregional and international trade.)

The Qing monetary system, from the perspective of the present, may appear cumbersome and complex. However, the intricacies of the Qing currency did not prevent the Empress of China from securing a large profit.

Chinese coins from the Tang to the Qing dynasties (618-1911).

Hearing the news, John Adams wrote to John Jay that “there is no better advice to give to the merchants of the U.S. than to push their commerce to the East Indies as fast and as far as it will go.” Merchants listened that advice and set sail to China.

Bound by Silver

Over the course of the 19th century, the Qing dynasty suffered from foreign wars and internal rebellions. After its Civil War, the United States took the first steps toward becoming an international economic power.

(Left) An 1898 French cartoon depicting England, Germany, Russia, France, and Japan dividing up China while a stereotypical Chinese official ineffectually tries to stop it. Largely predating American expansion efforts toward China, the U.S. was not included. (Right) The 1901 cover of Puck, a satirical magazine. Columbia, the personification of the United States, puts on a warship-shaped hat representing the United States’ grab for “World Power,” which would include more influence over Chinese trade.

Silver increasingly bound the two countries together: the United States became one of the chief producers of the metal after the discovery of the Comstock Lode in Nevada and the Qing was the most populous place that remained on the silver standard as many nations, including the United States, switched to gold.

After much discussion and controversy, the United States moved toward the gold standard in the 1870s. The Coinage Act of 1873 took away the legal tender quality of the one silver dollar coin that had been a part of Hamilton’s original legislation.

Soon thereafter, the Coinage Act of 1873 became known as the “Crime of 1873” for, its critics claimed, surreptitiously putting the United States on the gold standard. The bill ultimately framed American economic and political debates of the 1880s and 1890s as Williams Jennings Bryan and others lashed out against the gold standard.

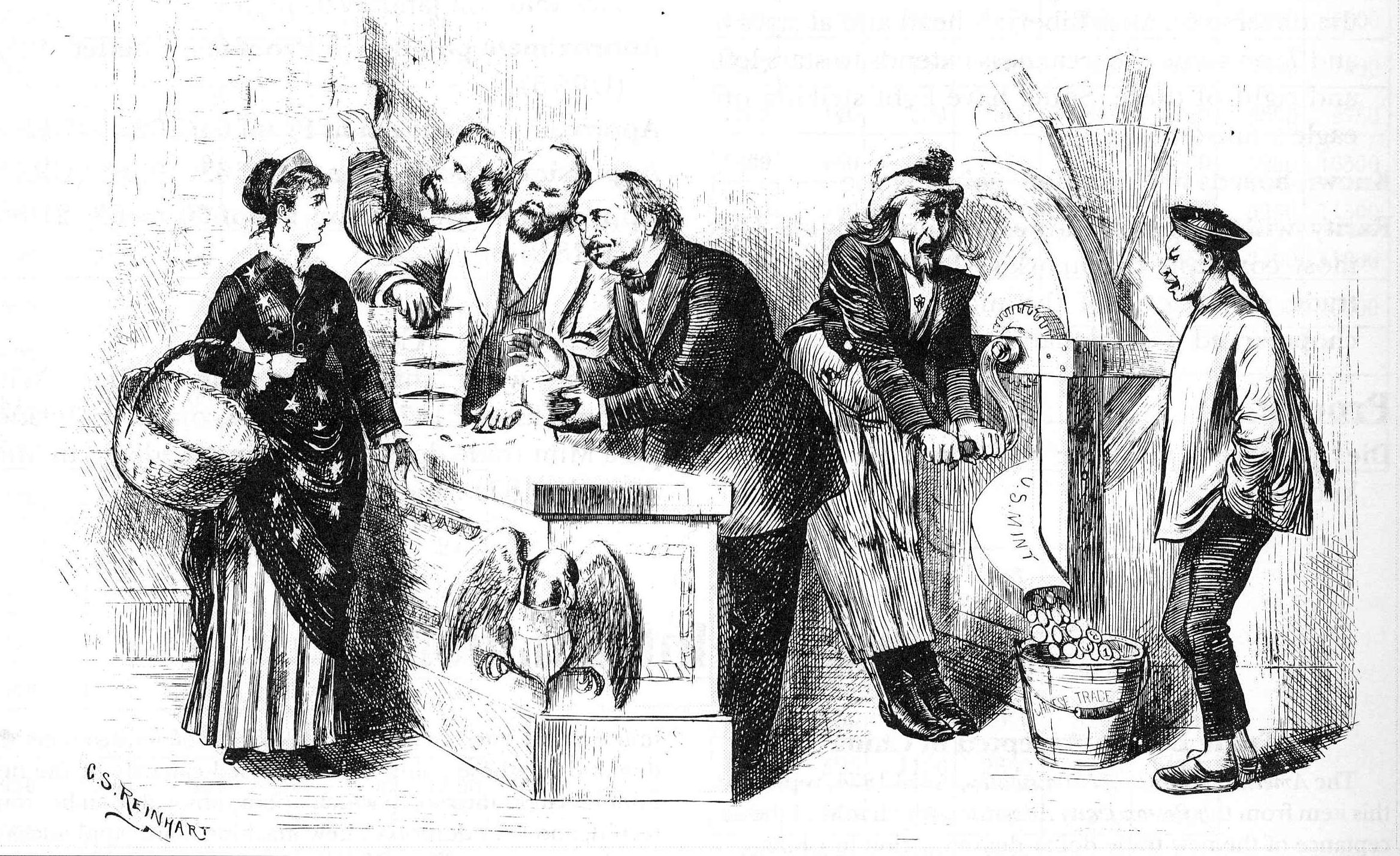

But the Coinage Act of 1873 also did something else: it created a special coin, the U.S. Trade Dollar, to be used in commerce with China.

Previous U.S. silver dollar coins had not been welcomed by Chinese merchants, who still preferred Spanish or Mexican silver dollars.

With the Comstock Lode silver mines proving some of the richest deposits in the world, but with the United States heading toward the gold standard, the U.S. Trade Dollar was meant as an outlet for American silver. American politicians and traders hoped that the new coins would become Chinese merchants’ dollar of choice.

The Trade Dollar did find a few footholds in the south of China, where silver coins were commonly used, but the coin was “chopped” by Chinese merchants with stamps of small Chinese characters to attest that is was a real coin. American officials complained that these “chopmarks” defaced a beautiful coin. Other coins ended up in the melting pot as they were heavier, and thus contained more silver, than many of the other coins circulating at the time.

The creation of the Trade Dollar was the first attempt by Americans to influence China’s currency by creating a market for American silver. It was hardly America’s last foray into the Chinese currency system.

Imperialism and the Chinese Currency

At the end of the 19th century, the Qing dynasty suffered a number of blows.

Qing forces defeated by Japanese troops during the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895).

In 1895, Japan defeated the Qing in the first Sino-Japanese War. The Qing granted Japan a number of concessions and also had to pay a large indemnity. Several years later in 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, a band of mystics tried to expel the foreign population from China but were ultimately defeated by an army composed of eight imperial powers. Afterward, foreign countries, including the United States, saddled the Qing with another huge indemnity.

In the first two decades of the 20th century, China became a center of great-power political competition as European countries, Japan, and the United States both cooperated and clashed over loaning money to the Qing and how China should reform its currency to facilitate trade.

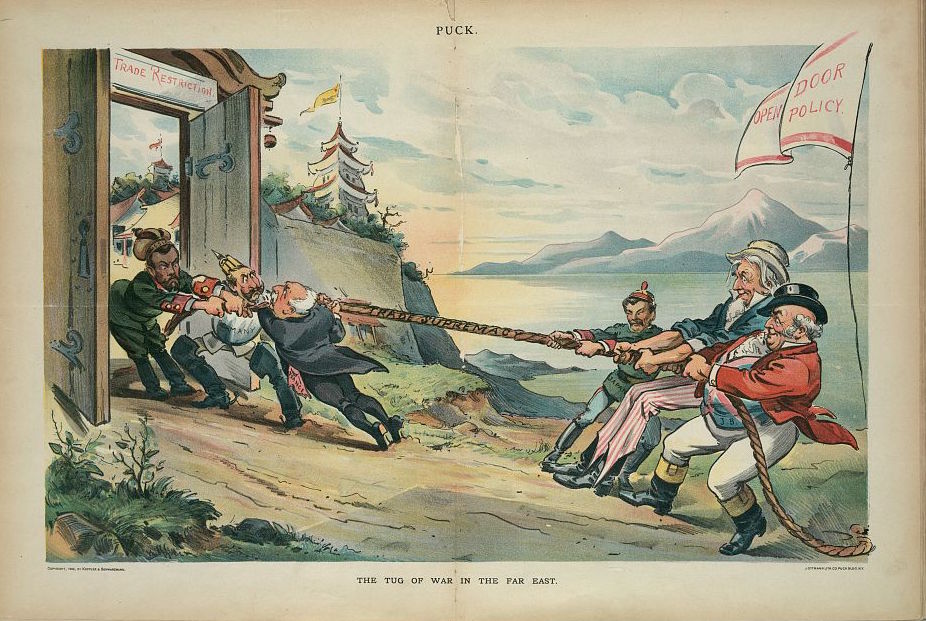

As the Qing dynasty faltered, the United States issued the “Open Door” notes. The goal of the notes, issued by Secretary of State John Hay, was to maintain equal commercial opportunities for all nations in China. Hay hoped to prevent any imperial power from exercising exclusive power over the trade, politics and administration of China. However, the policy was aspirational and the United States lacked the means to enforce its vision.

One way the United States tried to realize the Open Door policy was through issuing loans to the Qing dynasty. In the first decade of the 20th century, the Qing borrowed a significant amount of money to pay off debts and for a series of modernization projects.

The Qing was a good borrower, not defaulting on any payments. Qing officials were also savvy, often playing bankers from different European countries against one another in order to secure better terms. European bankers were themselves no fools and soon formed a banking consortium so the Qing could no longer negotiate for better deals.

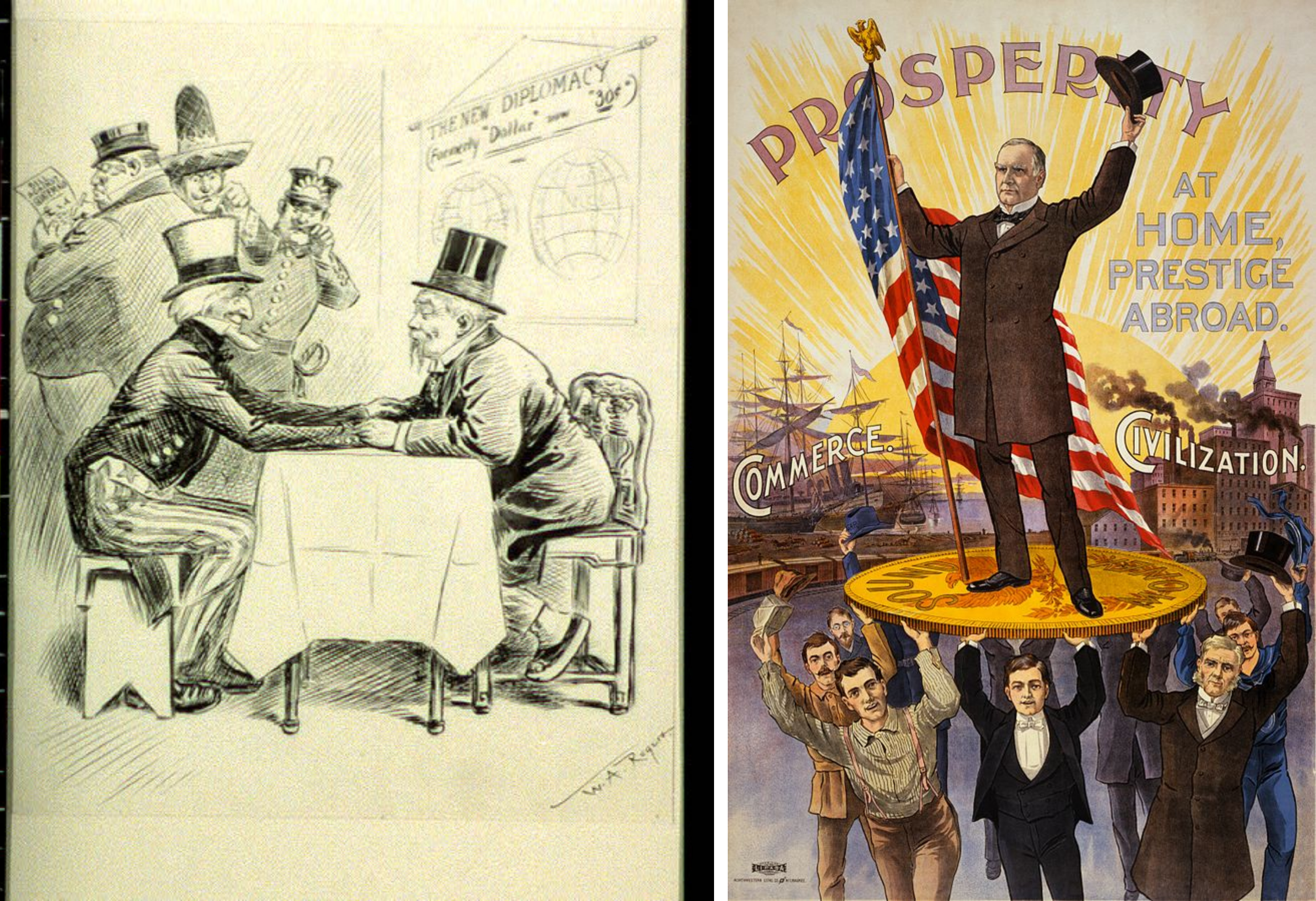

A political cartoon from 1913 in which Uncle Sam sits at a table with a Chinese official while representations of Great Britain, Mexico, and Japan look on. The sign in the background reads: "The New Diplomacy formerly dollar, now 30 [cents]" (left). William McKinley (right) ran for president in 1896 on the promise that adopting the gold standard would ensure U.S. prosperity.

The United States government wanted American bankers to join the international consortium. At the time, President William Howard Taft (1909-1913) pursued a policy of "dollar diplomacy," which entailed diplomats and bankers working together to loan money to countries and projects in Latin America and Asia.

In 1910, a consortium of American banks led by J.P. Morgan agreed to loan money to the Qing for the development of Manchuria and to reform the Chinese currency system. For the Qing, the purpose of the loan was expressly political. The government sought to balance the growing Japanese presence in the northeast by drawing American economic and political interests into the area.

Soon after in 1910, a consortium of English, French, German, and American banks signed a contract with the Qing for Manchurian development and currency reform, a short time before the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912.

That year was also a significant one in American politics as Woodrow Wilson became president. Upon taking office he recognized the fledging Chinese republic under the Hawaii-educated Sun Yat-sen and looked forward to the flowering of democracy in China. Wilson went even further and withdrew the United States from the international banking consortium it had only recently joined.

A poster commemorating the Republic of China, Yuan Shikai (left), and Sun Yat-sen (right).

The political and economic situation in China was precarious. Yuan Shikai, a key military figure under the Qing, seized power from Sun who ultimately fled to Japan to regroup. Yuan, helped by a loan from the international banking consortium, consolidated power in the period before World War I.

The outbreak of World War I changed the contours of East Asian politics. Japan entered the conflict on the side of the allies and seized German islands in the Pacific Ocean as well as the German treaty port of Qingdao on China’s Shandong peninsula.

The Japanese government soon sent Yuan Shikai a document known as The Twenty-One Demands that, taken together, would give Japan unprecedented control over the political, economic and military affairs of China. Yuan played for time, hoped for an American intervention that did not come, signed some of the demands and relied on leaking the contents to create international objections in order to stave off the worst clauses.

|

| A Japanese Yen bank note from 1873. The Continental Bank Note Company of New York printed the Yen for the Japanese. |

While most of the world focused on the conflict in Europe, Japan sought to take advantage of the increasingly unsettled situation in China. Yuan’s acolytes and associates then vied for power. Japan again tried to take advantage of the situation, arranging for merchant and middleman Nishihara Kamezo to seal a number of loan agreements with the nominally national government under one of Yuan Shikai’s associates.

One of these loans related to currency reform and specified that the Chinese currency would be linked to the Japanese yen in an emerging currency bloc.

This step roused objections from the United States. In 1917, the American minister in Beijing cited America’s “long-standing interest” in the question of currency reform in China and protested the recent loan agreement.

He was not the only one.

The Chinese populace protested against the terms of a number of the Nishihara loans. At the same time, American diplomats and bankers maneuvered to reenter and reform the international baking consortium it had left at the beginning of the first Wilson administration.

As world leaders met at Versailles to usher in a new world order after the First World War, bankers labored over an agreement to reform the international banking consortium.

After the Treaty of Versailles, China continued to fracture. Though there was a nominally national government in Beijing, a number of warlords held power in different regions of the country.

Chinese students protesting the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

Sun Yat-sen, returned to China and his political party, the Nationalist Kuomintang (KMT), had a foothold in the far south. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—formed in 1921—was still a small organization. Sun, thinking the two groups had similar short-term interests, formed an alliance, though he died soon thereafter.

By the late 1920s, the KMT, then under the control of Chiang Kai-shek, marched north hoping to unify the country and end the rule of various warlords. Chiang, suspicious of the CCP and its revolutionary doctrine, also used the march to purge communists from the ranks of the KMT. The CCP fled to the countryside and the Nationalist party consolidated power, established its capital in Nanjing, and embarked on what became known as the Nanjing Decade, 1927-1937.

|

| Chiang Kai-shek, leader of the Nationalist, Kuomintang (KMT) party, in 1943. |

At the time the KMT consolidated power in the late 1920s, China was still on the silver standard monetary system. From the late 19th century through the 1920s, the price of silver continually declined as most countries adopted some form of the gold standard. Though the price of the metal rose briefly during World War I, it sank throughout the 1920s.

This trend made Chinese exports cheaper and conversely raised the price of imports from abroad. As the Great Depression spread across the world in the late 1920s and early 1930s, China initially avoided the worst of its effects, in part because its silver-based currency floated in relation to the currencies of nations on the gold standard.

However, certain American politicians had a different idea about the role of silver in China. Efforts on the part of the United States to manipulate Chinese currency took new, more urgent directions.

The Great Depression and World War II

Key Pittman, a senator from the key silver-producing state of Nevada, explained the Great Depression this way: Because the price of silver was so low, Chinese could not afford to import goods from abroad, particularly from the United States. The drop in the price of silver led to a glut of products that might have been sold to Chinese consumers and a slowing of commerce.

|

| U.S. Senator Key Pittman of Nevada in the 1930s. |

He believed that if the U.S. government took action to raise the price of silver by buying it at above-market prices, the average Chinese consumer would be able to afford the products of the world and slow economic conditions would end.

As Pittman explained in a letter to an acquaintance in the early 1930s, “If silver is stabilized at a reasonable value to satisfy the Oriental, then he will part with his silver and business will go on. If, however, the stabilized value is too low a figure, his silver will remain where it is and there will be no trade developed.”

Pittman’s explanation for the Great Depression centered on silver prices and China. His proposal, he argued, would benefit China, the world economy, and, conveniently, silver producers in his home state.

Many in China objected to Pittman’s argument. They believed that an artificial increase in the price of silver would have disastrous consequences. Silver would become more valuable as bullion on the international market than as coin in China. Under these conditions, silver would leave China. Since silver was money in China less of it would lead to deflation, exactly what China had avoided in the initial years of the Great Depression during the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Chinese protests and lobbying efforts did not prevent Congress from passing the Silver Purchase Act of June 1934. Under the Act, the Treasury Department would purchase silver until its price on the world market reached a certain level. The idea, as Pittman explained it, was to stimulate a rise in the metal’s price that would increase the purchasing power of the world, particularly of Chinese consumers. Secretary Henry Morgenthau pledged to carry out the policy and began buying silver at above-market prices later that summer.

Predictably, silver soon began to flow out of China.

By October, the Chinese minister of finance, Kong Xiangxi, a graduate of Oberlin College, asked Morgenthau to curtail the silver-buying program.

Arthur Young, one of Kong’s American advisors, surmised that the Chinese government only had a few options going forward: it could put a tax on the export of silver, which might ease things in the short term but which would undoubtedly encourage smuggling. Or, it could undertake a longer-term change to its monetary system.

In 1935, Morgenthau continued with purchases of silver and Chinese officials plotted their next move.

In November 1935, the Chinese government announced the end of the silver standard and the start of the fabi, a legal tender currency issued by the government, which promised to maintain exchange rates with the American dollar and British pound at certain levels. Everyone in China had to turn in silver for the new notes.

|

| A 5 Yuan bank note from 1936 meant to replace silver coins. Notably, the bank note resembled the American dollar and included English words. |

However, a significant problem haunted the new currency system. Most of the Chinese reserves were denominated in silver, not dollars or pounds. Now that the Chinese government had control of the nation’s silver, it sought to sell the metal for foreign currency. The Chinese minister of finance soon dispatched Chen Guangfu, a banker and University of Pennsylvania graduate, on a round-the-world trip to Washington.

The Americans did not quite know what to make of the new Chinese currency. Was it linked to the British pound or the U.S. dollar? If it was indeed linked to the British pound, Morgenthau surely could not assist the Chinese by purchasing silver. The optics would be awful. Likewise, Pittman and the silver bloc wanted to ensure that there would be at least some market for silver in China.

After several weeks of negotiations in spring 1936, Morgenthau and Chen reached an agreement concerning continued American purchases of silver. As Morgenthau told Chen, with America the largest buyer of silver and China the largest seller, the two of them could put the metal’s price anywhere they wanted.

During the next two years, the new fabi maintained its value and the move off silver went much better than many foreign and Chinese observers expected. But the Japanese invasion of China in 1937 irrevocably changed that.

As the Japanese Imperial Army swept across north and east China in 1937 and 1938, Chiang Kai-shek and the KMT government retreated deeper into the center of the country, eventually establishing a base in mountainous Chongqing. Japan set up a number of banks in areas under its control that issued their own currency and tried to undermine the value, reputation, and prestige of the fabi.

|

| A U.S. propaganda poster from the 1940s promoting the United China Relief fund. |

The Japanese invasion was a currency war as well as a military one.

The value of the fabi eroded, first gradually, and then precipitously. The KMT financed growing budget deficits through the printing press, which, the story goes, worked without interruption, needing a continuous supply of paper and ink to churn out notes. Inflation soared; it took bricks of cash to buy basic items; and uncertainty and discontent increased. After the United States entered the conflict, more financial aid arrived but the Chinese insisted it was not enough.

After the end of World War II, the conflict between the KMT and CCP resumed. The KMT tried one last effort at currency reform in 1948 but it was not successful. Deteriorating economic conditions and a series of CCP military victories made the KMT position in the mainland untenable. It soon fled to Taiwan.

The CCP announced the founding of the People’s Republic of China on October 1, 1949. In the United States, many spoke of the “Loss of China.” If only the United States had done more to support Chiang Kai-Shek and the KMT, the thinking went, the communists would have never gained power.

The People’s Republic of China and the Renminbi

The new Chinese Communist Party faced myriad challenges after the start of the PRC. Currency reform was just one of them. In the late 1940s a number of different notes circulated. The People's Bank of China began issuing the renminbi, the people's currency, in 1948 in the the territories under its control.

Starting in 1948, the renminbi, known as the people’s currency, featured images of peasant farmers and industrial workers. From left to right: 1 Yuan Note, 5 Yuan Note, and 200 Yuan Note.

At the time, the People’s Republic of China deliberately overvalued the renminbi and put strict controls on its convertibility: it was not easy to change renminbi for American dollars or British pounds. The purpose of overvaluing the renminbi was to make it less costly to import foreign machinery to be used to produce for the domestic market.

The PRC traded with a number of countries, just not with the United States. The currency question, uncharacteristically in the history of Sino-U.S. relations, was a dormant issue, but not for long.

After President Richard Nixon’s trip to China in 1971, the death of Mao Zedong in 1976, and the economic policies of Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s and 1980s, relations between the United States and the People’s Republic of China resumed and trade between the two countries picked up.

President Richard Nixon and Premier Zhou Enlai toasting during Nixon's historic visit in 1972.

Starting from the 1980s, the value of the renminbi declined in order to promote Chinese exports. In 1980, one American dollar could only buy about 1.5 Chinese yuan (yuan is a denomination of renminbi) but by the mid-1990s the same American dollar could buy around 8 Chinese yuan.

From the late 1990s to the mid-2000s, the People’s Bank of China maintained the value of the renminbi at a peg to the dollar. At the same time, China accumulated a growing current account surplus—it exported significantly more than it imported. Under these circumstances and over time the value of renminbi should rise. However, because the People’s Bank of China maintained the currency peg, it did not.

Because of this, in the early and mid-2000s a number of American politicians and economists sought to label China a “currency manipulator” and try to force appreciation rise in the value of the renminbi.

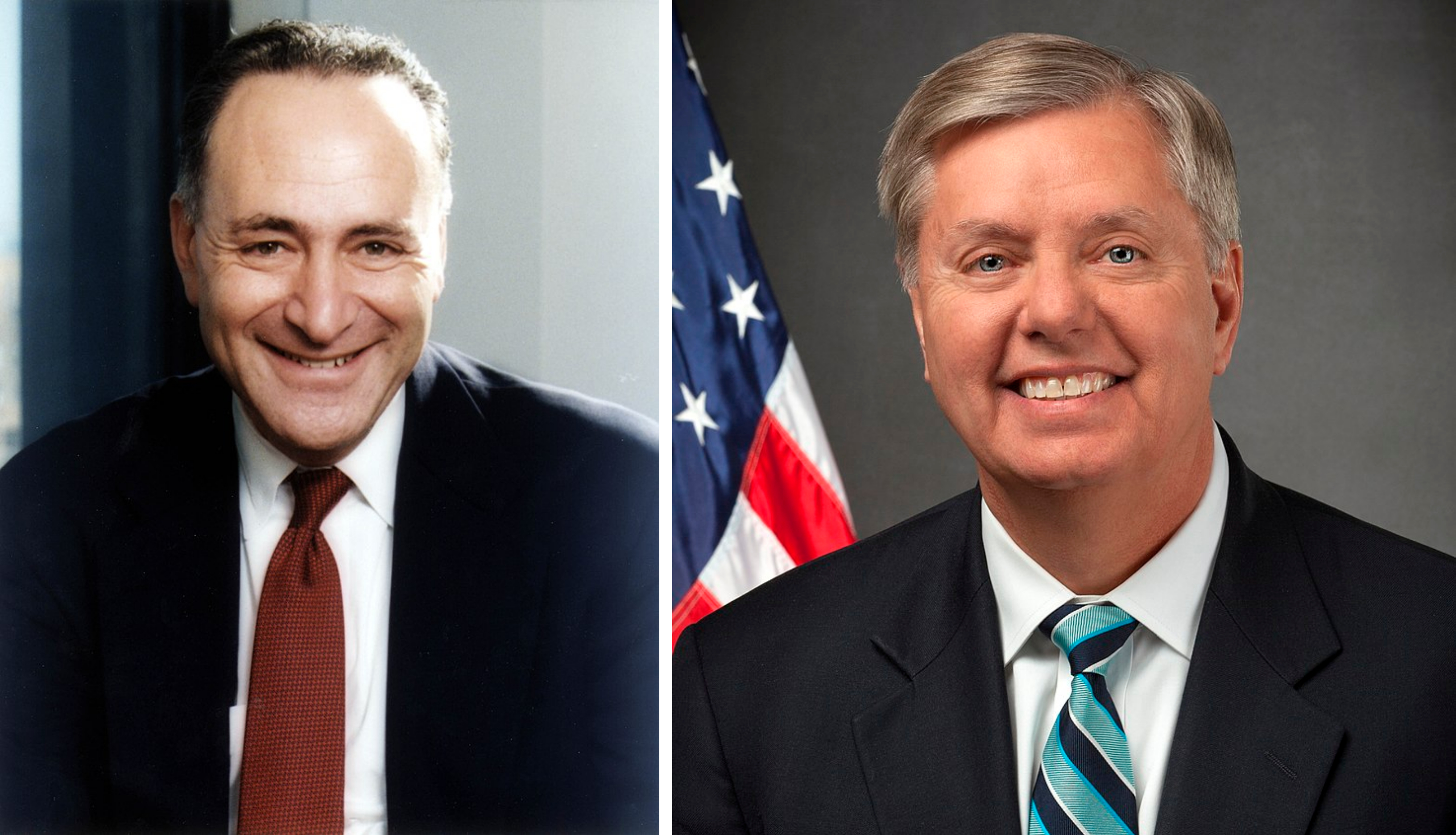

Democratic Senator Charles Schumer of New York (left) and Republican Senator Lindsey Graham of South Carolina (right).

The issue brought together unlikely political allies. In the U.S. Senate, Charles Schumer (D-NY) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) repeatedly sponsored bills and lobbied the Treasury Department, the organization in charge of making the final decision, to pressure the Chinese currency.

In 2005, the People’s Bank of China allowed the RMB to appreciate slightly. But this change should not be totally attributed to American pressures. Plenty of figures within China disagree about how to handle the value of the RMB.

China faces what economists call the “trilemma.” In making monetary policy, a country cannot have everything it wants. It has to make choices. It cannot have a fixed foreign exchange rate, control over its own monetary policy, and free movement of capital. For example, the United States sets its own monetary policy and allows for the free movement of capital—investors can move dollars in or out of the U.S as they please—but the value of the dollar in terms of other currencies moves around.

The headquarters of the People's Bank of China in Beijing.

Different parts of the Chinese government and the Communist Party disagree about what path to pursue. If the People’s Bank of China allows the value of the renminbi to float and capital to flow in and out of China freely, that means the CCP would lose a great deal of control over the economy, something many in the party and state are likely unwilling to give up.

If it chooses the other route and tries to keep the exchange rate that moves only within a very small margin, it must maintain capital controls—limiting the amount of money people can move out or move into the country. At the moment individual Chinese citizens are only allowed to trade RMB for dollars up to the amount of $50,000 each year, though there are a number of ways to skirt this requirement and there is evidence that Chinese are moving large sums out of the country.

Age of Uncertainty

Throughout the 2016 presidential campaign, President-elect Donald Trump accused China of manipulating its currency by keeping it too low. Yet in reality, in the face of a dramatic economic slowdown, the People’s Bank of China has recently intervened to keep the value of the renminbi artificially high.

There are a number of reasons behind this shift in economic conditions: the sense that the export-led growth model of the past 30 years is coming to an end, a declining number of viable investment opportunities, pessimism about the debt levels in China and a desire to diversify into assets outside the country.

The much-heralded Chinese currency reserves declined as people traded their RMB for dollars. Since the Chinese government promises to keep the renminbi at a certain level it has to use its dollar reserves to maintain that level. If, instead, it let the value of renminbi float on the open market, it would likely be lower than it is today.

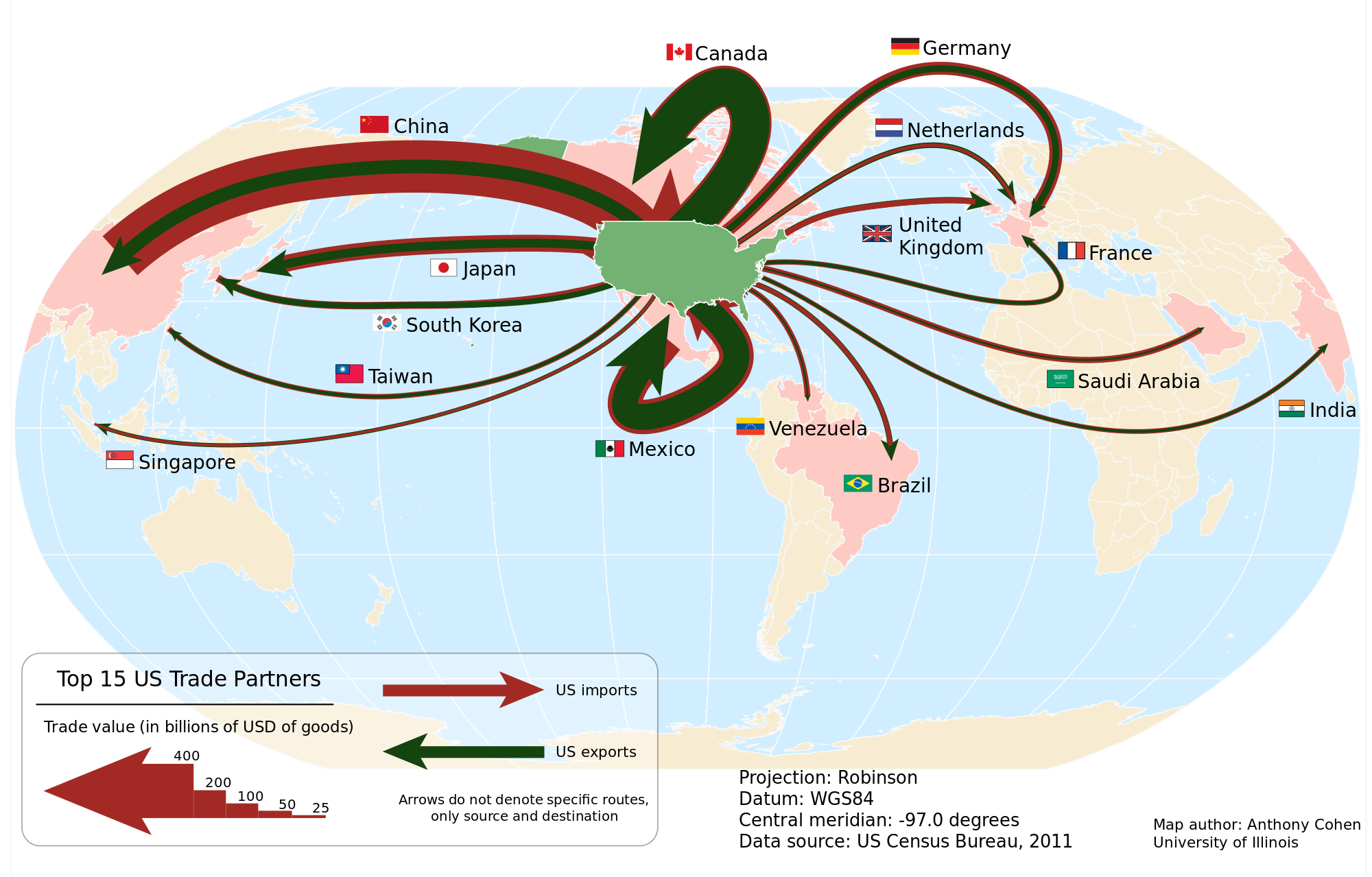

The U.S.’s top trade partners in 2011.

In the immediate aftermath of Trump’s election, uncertainty and volatility around the world shot up and a number of markets went down: the value of the Mexican peso, for instance, was decimated. After one of the most stunning political feats in American history, commentators are rightly hesitant to make any prognostications, but here is a conservative one: the currency question in U.S.-China relations will soon reemerge.

For more than 200 years, American merchants, Qing dynasty officials, Communist party cadres, and American politicians pondered how to manage the trade and currency relations between the two countries. These debates spanned the era of Spanish silver dollars, the gold standard, the Great Depression, World War II, and the Reform and Opening of China under Deng Xiaoping.

In past election cycles it was common for candidates to bash China during the election before changing their rhetoric when confronted with the complex, shifting and multifaceted nature of U.S.-China relations. Author James Mann calls this process the "about face." For the past 25 years, the "about face" of those presidential candidates who later became presidents became predictable and expected.

The reliable "about face," like so much else in the world, is now shrouded in uncertainty.

Read more on Asia from Origins: The China Dream; China and Africa; Remembering Tiananmen; Hong Kong; Taiwan’s Politics; The Chinese Cultural Revolution; The Philippines and Pacific Geopolitics; Japanese Nuclear Power; Singapore at 50; and North Korea.

Bell, Stephen Bell and Hui Feng. The Rise of the People’s Bank of China: The Politics of Institutional Change. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013.

Donlin, Eric. When America Met China: An Exotic History of Tea, Drugs, and Money in the Age of Sail. New York: Liveright, 2013

Kroeber, Arthur. China’s Economy: What Everyone Needs to Know. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Mann, James. About Face: A History of America’s Curious Relationship with China, from Nixon to Clinton. New York: Vintage Books, 2000.

Rosenberg, Emily. Financial Missionaries to the World: The Politics and Culture of Dollar Diplomacy, 1900-1930. Durham: Duke University Press, 2004.

Young, Arthur. China’s Wartime Finance and Inflation, 1937-1945. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1965.

Young, Arthur. China’s Nation-Building Effort, 1927-1937: The Financial and Economic Record. Palo Alto: Hoover Institute Press, 1971.