October 30, 1938. The first signs were those explosions.

The news interrupted the regular Sunday night CBS orchestra, with Ramón Raquello’s ensemble playing a Spanish tune. According to the alert, “Professor Farrell of the Mount Jennings Observatory, Chicago, Illinois, reports observing several explosions of incandescent gas, occurring at regular intervals on the planet Mars.” Whatever was happening, the gas was moving at enormous speed straight at earth.

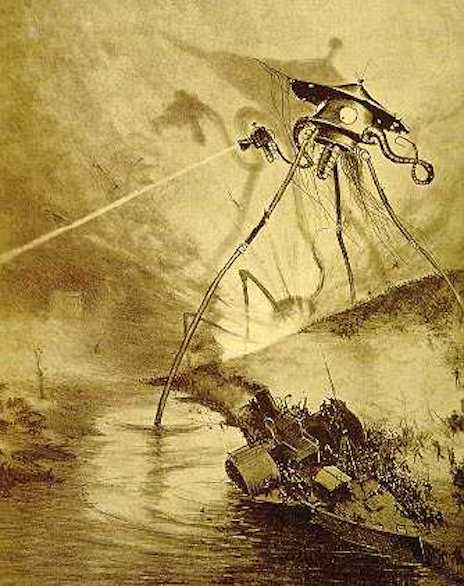

H.G. Wells’s novel, War of the Worlds, described hissing, tentacled, tripodal invaders from Mars.

Carl Phillips, an enterprising radio newsman unsatisfied with the comments from an obscure Midwestern astronomer, sped to Princeton to get the scoop from world-famous Princeton Professor Pierson. The good professor dismissed any concern. The explosions were “merely the result of atmospheric conditions peculiar to the planet,” he declaimed. As for life on Mars, the odds were “a thousand to one.”

Then they arrived, as if to mock the best expertise that these simple humans could present. The invaders smashed into the Wilmuth farm in Grover's Mill, NJ, virtually on Princeton’s doorstep. By the time Phillips got there, hundreds of curious locals surrounded the scene. But the intrepid reporter muscled his way, microphone in hand, directly in front of the fantastic events.

A historical marker in Grover's Mill, NJ commemorating the “Martian landing site” of Welles’s broadcast.

It was a fatal decision. Within minutes, hissing, tentacled monsters emerged from the wreckage. Shooting flames from small, mirror-like weapons, they laid waste to everything in front of them—bystanders, police, Professor Pierson, “the woods . . . the barns . . . the gas tanks of automobiles,” and then Phillips himself. The microphone went dead.

The War of the Worlds was underway. Annihilation loomed for the human race.

The original broadcast of Orson Welles's production of War of the Worlds by H.G. Wells.

This was the narrative of perhaps the most infamous radio broadcast ever: Orson Welles’s Halloween adaptation of the H.G. Wells novel, War of the Worlds, which aired for the first time 80 years ago.

Only twenty-three-years old, Welles already had established himself as a theatrical genius. The “Wonder Boy of Broadway,” he had produced a version of Julius Caesar set in Fascist Italy, then Macbeth with an all-African American cast, for New York’s Works Progress Administration theatre project.

Welles had already established himself as the “Wonder Boy of Broadway” with an all-African American production of Macbeth.

He dabbled in radio for the money, and his voice became familiar as “The Shadow” from a children’s show. With John Houseman, he established the CBS Mercury Theatre after the WPA project shut down, and together they produced both regular plays and weekly radio dramas. “War of the Worlds” was just another of those dramas.

But of course it wasn’t. Though introduced in the usual way and even interrupted with the regular intermission, the broadcast set off a nationwide panic.

Welles’s voice became familiar to (some) radio listeners as "The Shadow."

Thousands of people fled their homes on reports of Martian gas, their mouths covered with handkerchiefs and towels. Police stations and newspapers were inundated with hysterical phone calls. Hundreds of nurses and doctors offered their services to hospitals for the emergency. A man in Pittsburgh caught his wife as she prepared to drink a bottle of poison. Two people reportedly died from heart attacks. The Washington Post declared Americans downright “radiotic.” Within days, congressional inquiries were calling for censorship.

Whatever the immediate public consequences, Welles’s production confirmed the solidifying public consensus among Western intellectuals that modern forms of mass media—Hollywood and radio—were pernicious agents of “mass culture.”

According to this burgeoning perspective, mass-produced entertainment corrupted youth, pushed out high-minded practices such as reading, and peddled cultural sewage that appealed to the lowest-common denominators of taste. Originally sprung from moralizing attacks on movies, mass-culture theory took increasingly political tones and absorbed Freudian-Marxist cultural critiques, not least because Mussolini and Hitler both had used radio effectively to stir up the folk.

Welles’s production confirmed the solidifying public consensus that radio was a pernicious agent of “mass culture,” not least because Mussolini and Hitler both had used radio effectively to rally support.

Indeed, even as Welles was running Mercury, a group of researchers at Princeton were conducting the first serious studies of the effects of mass communications on audiences.

For Hadley Cantril and his colleagues, “War of the Worlds” presented mass-culture effects in crystalline form. In the book Invasion from Mars (1940), Cantril painted radio listeners as gullible fools. Of the estimated six million who listened, 1,700,000 mistook it for real news, and 70 percent of them became scared.

For many, the program’s realism, with its references to familiar landmarks and well-known towns, was convincing. Others simply took it for granted that what was on the radio had to be true. “I just naturally thought it was real,” one woman explained. “Why wouldn’t I?”

Welles explained to assembled news reporters that the crew of the broadcast of War of the Worlds was surprised by the public’s reaction.

Because so many Americans by then were using the radio as their principal source of information, they were accustomed to taking it at face value. The voices of authority—government officials, the professor, the reporter—were all it took for them to assume that the invaders were churning through Grover's Mill.

Though Cantril found that the most common reason why people took the broadcast as fact was that they tuned in late and missed the disclaimer at the beginning, Cantril took little relief. Even late listeners should have been curious enough to verify what was happening. The whole episode was mass persuasion on a grand scale, and Cantril was not alone in seeing it as such.

Journalist Dorothy Thompson thought it revealed “the incredible stupidity and ignorance of thousands” and proved how easy it was “to start a mass delusion.”

The panic vividly revealed how fascism worked and indicated that Americans were profoundly vulnerable to “popular and theatrical demagoguery.” Welles shed more light on “Hitlerism, Mussolinism, Stalinism, anti-Semitism and all the other terrorisms of our times,” Thompson asserted, than any political pundit or scholarly observer.

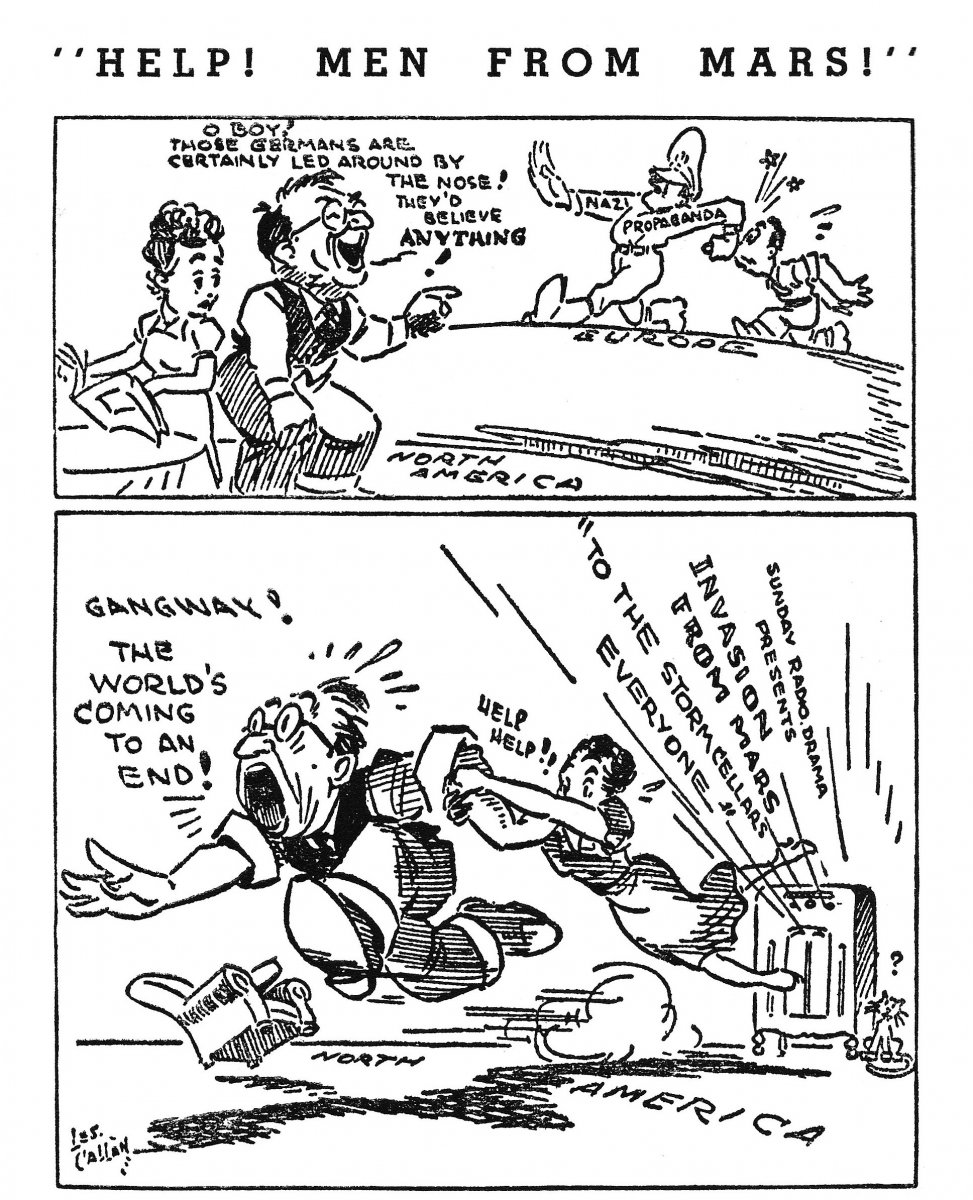

A Toronto Star cartoon from 1939 about Welles’s broadcast showed how a North American public was potentially just as susceptible to new forms of mass media, including radio, as a European one.

In the long run, the mass-culture theory of audience response dissolved. Its guiding presumption that media had “direct effects” on the audience was generally undermined in the 1950s, when the heirs to Cantril’s Princeton Radio Project introduced the “two-step” theory of effects. Then, in the 1960s, the adoration of “popular culture” and the theoretical conceit that people turn media to their own purposes pretty much buried the “elitist” perspective.

In our own moment of “fake news,” we might do well to recover mass-culture theory. Americans seem to have gone from a condition in which a fake war indisputably generated direct effects on the radio audience to one in which they swoon as they listen to a news-media-actor-cum-President—a mere carnival barker compared to Welles, the boy genius—who tells them that the truth is fake.

The current U.S. president has frequently claimed factual reports are in fact “fake news.” (Flickr – Gage Skidmore)

The direct effects of these performances are evident too. One wonders whether we’re not again in the presence of “a humped shape . . . rising out of the pit,” with eyes that “are black and gleam like a serpent” and “saliva dripping from its rimless lips that seem to quiver and pulsate.”

It should be enough to scare us all.