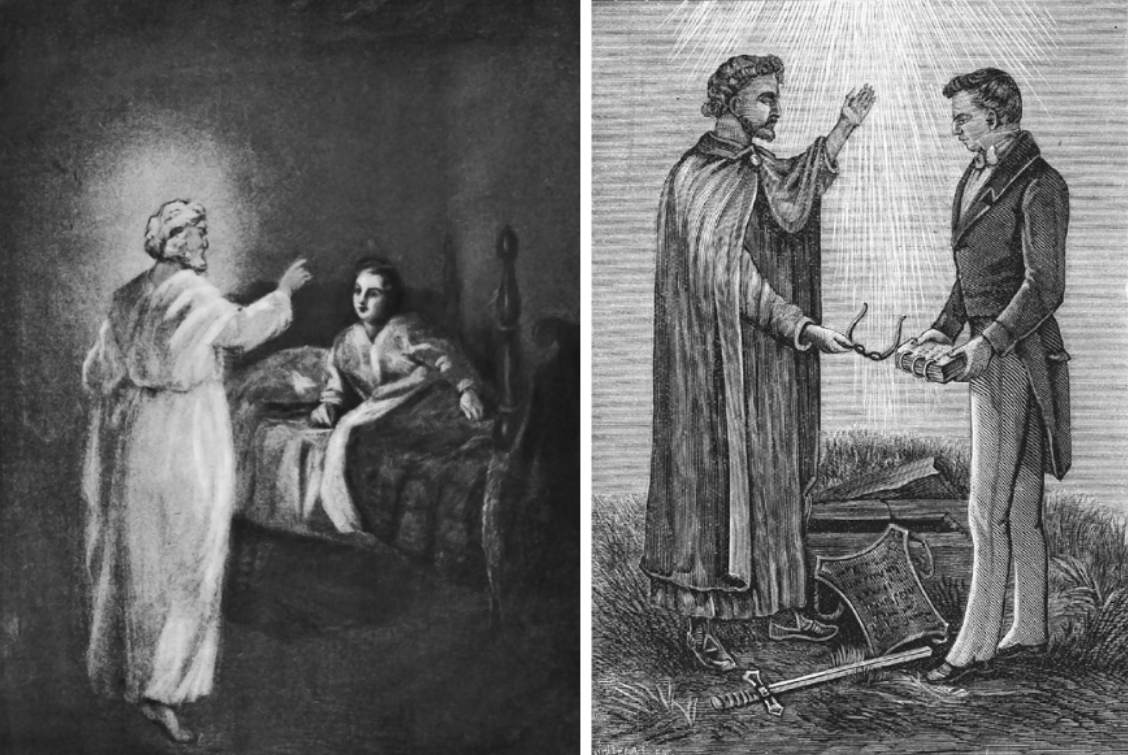

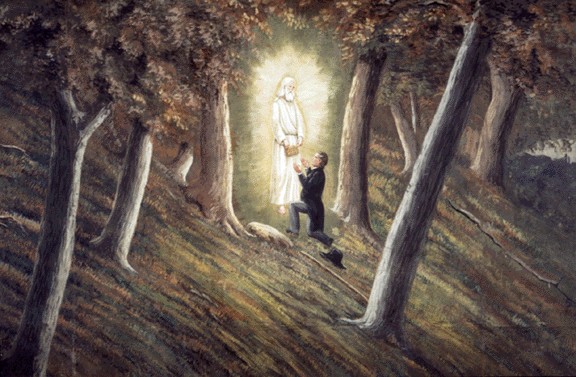

Few episodes of American religious history appear as unlikely as what Joseph Smith claimed to have happened to him on September 21, 1823. According to the traditional narrative of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Smith was visited that night by an angel who told him of an ancient record buried nearby his farm in western New York.

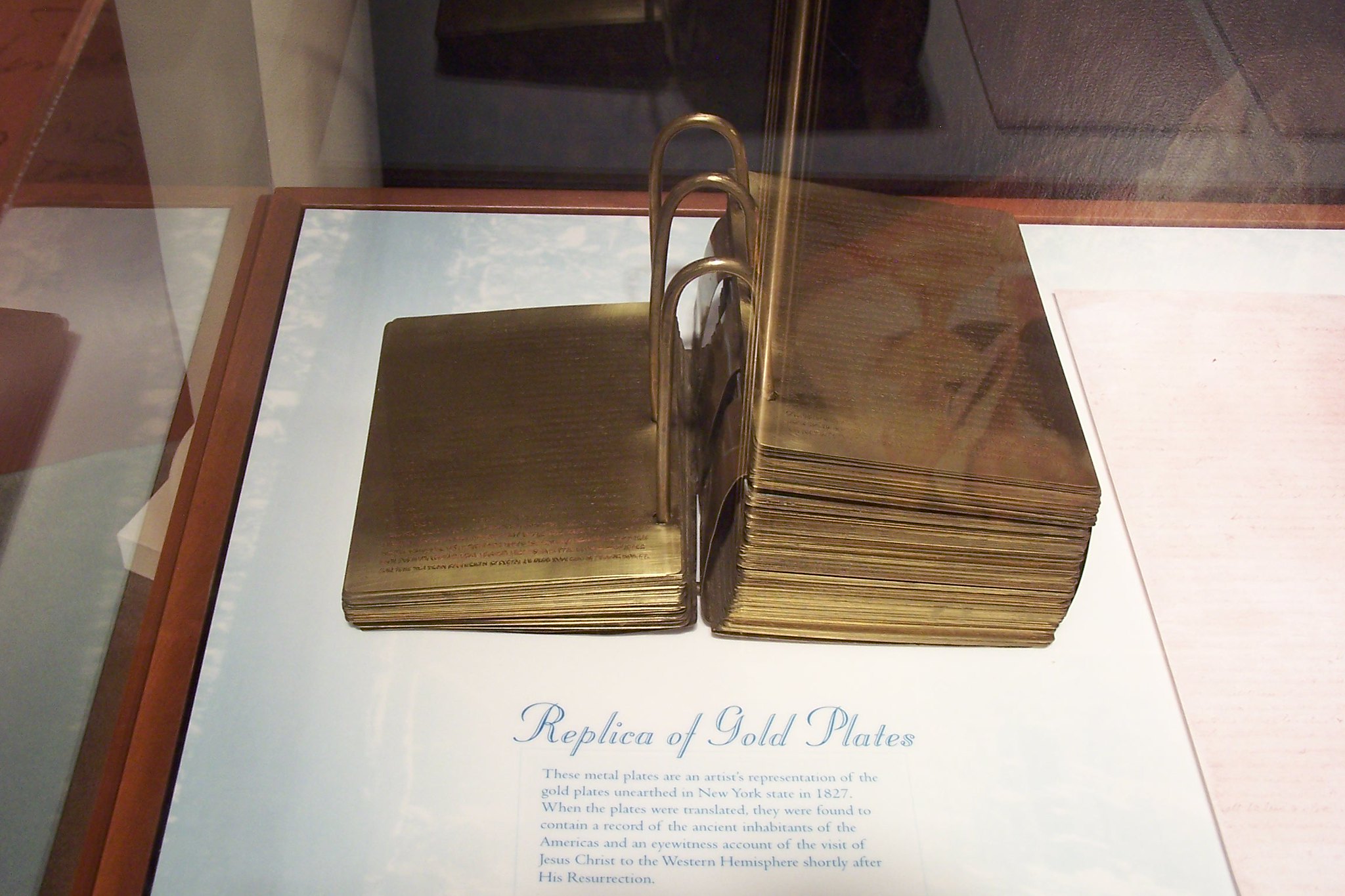

Smith traveled to the hill in question the next day and uncovered gold plates on which he claimed were written the history of a Christian civilization that lived in the Americas two millennia prior. Years later, when he eventually took possession of the plates, he “translated” them into the Book of Mormon.

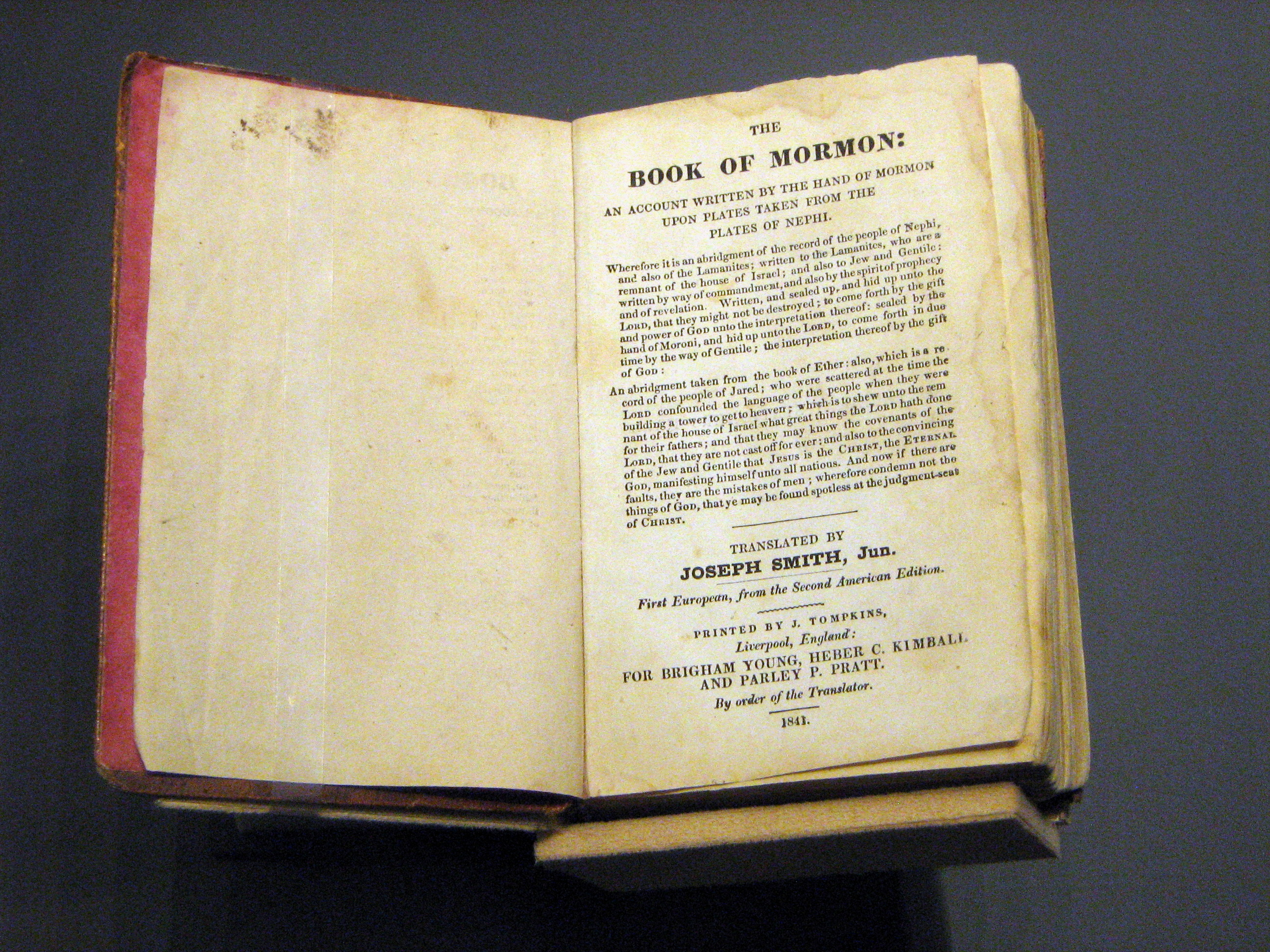

That text is now embraced as scripture by over 17 million worldwide members of the faith and has been translated into more than 100 languages. Even Smith’s narrative of the angelic visitation and reception of the plates is part of the church’s scriptural cannon. It is a story well known to American historians, frequently recited in religious studies classes, and often skewered in popular culture, e.g., the television show South Park.

But 200 years later, the story of how the Book of Mormon came to be remains a contested space between believers and critics.

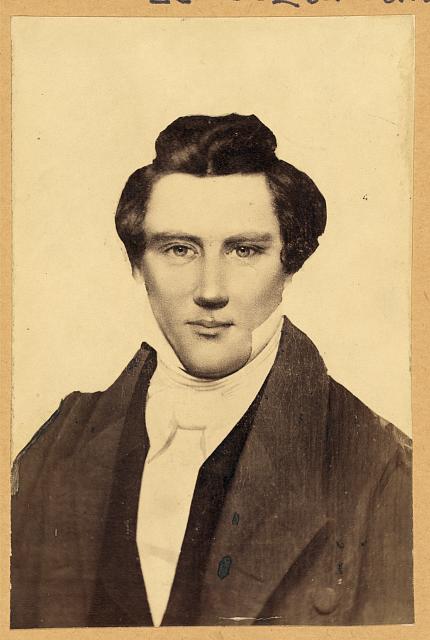

The young Smith was raised in a family that blended devout Christian piety with unorthodox exploration. His father, Joseph Smith Sr., dabbled in marginalized faiths like Universalism but mostly avoided organized denominations altogether. Joseph Jr.’s mother, Lucy Mack Smith, favored the Presbyterians but prioritized a vision of familial unity under Christ’s saving grace.

More pressing, though, was a series of failed financial schemes that forced the family of twelve to move from town to town. The Smiths were wanderers, physically and spiritually.

When Joseph Jr. claimed to receive a divine vision of God around 1820, he was fulfilling a family tradition. Both his parents, his maternal grandfather, as well as several of his aunts and uncles had also claimed visions and revelations. The story also fit within a broader context of religious seekers throughout the “Burned Over District,” as upstate New York was called, proclaiming a direct line to God.

The Smiths were equally enmeshed in another cultural practice of the day: treasure seeking. Joseph Sr. was, by the 1820s, a seasoned veteran of hunting for buried goods; Joseph Jr., likewise, quickly grew a reputation for being a skilled “seer.” He was known for being able to find hidden objects by looking into a seer stone, of which he had several. For many during this period, there was no incongruity between pious Christian faith and occult traditions.

In that context of both spiritual and folk obsessions, Smith first claimed to be visited by the Angel Moroni in September 1823. Smith had only recently hunted for treasure on the very hill that Moroni now told him contained gold plates. Yet he was also chided by the angel not to think of worldly riches, but rather of sacred truths, once he visited the burial spot the next day.

Smith alleges that the angel did not allow him to take the plates that year, or even the next few. Nor did he immediately have a renewed discipline for his life.

Both he and his family continued to wander and suffer through new crises. A court even tried him in 1826 for being a “glass looker.” After that point, however, the young seeker attempted to reform his ways: he participated in a string of revivals, married the pious Emma Hale, and hoped to win over his new in-laws.

The story of the gold plates evolved with these changing circumstances. By 1827, he spoke of it purely in religious, rather than treasure, terms. On September 22 of that year—he is said to have visited the hill every year on that date—he finally procured the plates.

His former treasure-digging colleagues believed he was withholding the long-desired fortune from them; his family and growing number of spiritual followers, conversely, were convinced he had recovered a sacred religious record.

It would take two years for Smith to produce the text that would immediately be accepted as scripture. The translation occurred, in part, through Smith using the same seer stone he had previously used in treasure quests.

The Book of Mormon, named after the figure within the story identified as the text’s primary editor, was published in late-March 1830, and the Church of Christ was organized a week later. Faithful “Mormons,” as they soon became known, attempted over the next decades to definitively distance their scripture’s origins from its folk-magic context.

For scholars, the story of the gold plates poses a fundamental problem. Do you take Smith at his word? Or do you assume he was a fraud? Answering those seemingly simple questions frames any ensuing analysis, as well as either alienates or endears opposing camps of readers.

A recent scholarly trend has attempted to find a middle path. Ann Taves, for instance, postulates that Smith may have envisioned creating the plates as a divine collaboration between himself and God, similar to Catholic priests performing transubstantiation. Sonia Hazard, meanwhile, theorizes that Smith’s gold plates story may have originated with encountering another new invention of the day: printing plates.

Two recent books published by Oxford University Press, timed to coincide with the anniversary of the gold plates story, have sought to place the episode within a much broader context. Richard Bushman, author of a popular biography of Smith, wrote Joseph Smith’s Gold Plates: A Cultural History, which examines how the idea of the plates has changed over the past two centuries, and what that history tells us about American society. And Grant Hardy, the foremost expert on the Book of Mormon text, has produced an authoritative edition within Oxford’s Annotated Bible series.

For two hundred years, Smith’s story of the Angel Moroni, the gold plates, and the Book of Mormon have captivated an American audience. There is little question that such interest will not subside in the next two hundred.