2015 marks the 50th anniversary of Singapore’s independence. And while many in the West have expressed deep concern over Singapore’s record on civil liberties and political restrictions, there is no question that the tiny island nation has emerged as major economic force not only in the Asia Pacific region but globally. This month, historian Derek Heng looks back over a much longer history to examine how Singapore emerged from the control of larger powers over several centuries. As Singapore celebrates, he reminds us that this port-city state, despite its many successes, has long remained an unlikely proposition.

Read more on Asia from Origins: The Philippines and Pacific Geopolitics; The China Dream; China and Africa; Remembering Tiananmen; Hong Kong; Taiwan’s Politics; Japanese Nuclear Power; and North Korea

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Singapore at Fifty

On August 9, 2015, Singapore celebrated its 50th year as an independent country.

From a meagre population of 150 when the British East India Company first set up a factory and trading post on the island in 1819, it has grown into a global city with a population of 5.5 million.

The city-state has attained the world’s second highest per-capita income. It has the planet’s second busiest port, its shipbuilding industry churns out the majority of all offshore oil rigs deployed globally, and it is the third largest international foreign exchange (FOREX) hub.

Commentators have often marveled at these rapid economic achievements, especially since so many people had declared upon its independence in 1965 that a small city like Singapore could not survive.

|

| The Singapore National Day Parade 2011. |

Over the past 50 years, its very existence has repeatedly been called into question by its own leaders, who have often argued that prosperity is not a given. They say history has demonstrated that city-states do not have good survival records; therefore independence cannot be taken for granted.

Indeed, throughout its documentable history over the past seven centuries, the small island of Singapore has lacked a substantial population, a geographical and economic hinterland, and an agrarian base. Autonomous existence has not been possible and Singaporeans have relied entirely on trade to obtain necessary goods.

To almost everyone, Singapore’s prosperity at 50 is remarkable.

|

| Lee Kuan Yew stands with President Ronald Reagan, Nancy Reagan, and wife Kwa Geok Choo in 1985 (left to right). |

How is it that a small, island city-state has been able to achieve such ends so quickly with so few natural resources? Could historical patterns help explain these economic and social successes?

Seeking answers to these questions, sociologists have studied Singapore’s demographic policies, social control mechanisms, and ethnic values. They have worked to explain what has often been perceived as a disciplined society espousing “Asian” values, associated with the Confucian value social system of northeast Asia.

Political scientists have deconstructed and drawn lessons from the statecraft and political control mechanisms of Singapore’s first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew and the system of one-party rule that has been in place since 1965.

And, yet, at the heart of it all are trade and global connections. Over the centuries, a variety of shifts in the global order have destabilized the region around Singapore and allowed the little port city to thrive.

Singapore’s First Attempt at Autonomy

Singapore’s small land area and proximity to the sea has meant that it is not a self-contained or self-sufficient geographical unit, but a coastal zone.

And Singapore’s geographical location at the nexus of the Indian and Pacific Oceans has meant that the islands in its vicinity have long been inhabited by people migrating across Maritime Asia.

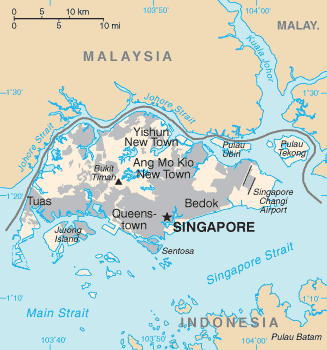

|

| A map of Singapore and the surrounding area. |

Situated at the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, at the confluence of the Bay of Bengal, South China Sea, and Java Sea, Singapore comprises a small handful of islets, with the main island having a land area of approximately 280 square miles. Until recently, Singapore has been characterized by low-lying mangrove-lined coasts interspersed with tidal creeks.

The earliest evidence for human habitation dates back to the Neolithic, while textual information on settlements in the vicinity date to as early as the first millennium CE. However, Singapore’s first documented settlement goes back to the late 13th century, when a port and polity was established at the mouth of the Singapore River.

Over much of its 700 years of documentable history, the island has been part of some larger entity, including: the kingdom of Srivijaya (modern day Sumatra, seventh to 13th century), the kingdom of Sukothai (modern-day Thailand, late 14th century), the Melaka Sultanate (1400 to 1510) and the Johor Sultanate (1511 to 1819), the British Empire (1867 to 1963), and independent Malaysia (1963 to 1965).

|

| Singapore was once part of the Srivijaya Empire, location pictured here. |

Since the seventh century, however, there have been two other periods when Singapore did emerge as an autonomous entity before its current state of independence.

Though relatively short, these periods beg the question: what enabled the island to break from the orbit of larger powers?

First, during the late 13th to late 14th century, the island was home to a port city, with its own ruler, stratified population, economy, and ritual center. Singapore's late-13th-century autonomy came when the Sumatran Empire of Srivijaya collapsed in 1275 after seven centuries of rule over the southern Melaka Straits and west Java Sea region.

This collapse, however, was instigated as early as the 12th century, when China's liberalization of mercantile shipping under the Song Dynasty (960 to 1278) led to the greatest expansion of the merchant marine in China's early modern history. Chinese shipping and trade began to systematically displace maritime Asian shipping and trade, which had hitherto been carried by ships of South Asian, Arab, and Southeast Asian origin.

In the process, ports and states in Southeast Asia, including Srivijaya, which had built its prosperity on facilitating the economic flows across Maritime Asia, began to decline in this new global economic environment. Smaller ports that could offer regional products directly to the Chinese traders, including Singapore, sprang up and prospered.

Other regional factors, including environmental events, also contributed to the growth of small ports in the region.

|

| Singapore rests on the strait of Malacca, a connector between the Pacific Ocean and the Indian Ocean. |

In the mid-14th century, an earthquake off the northeast coast of Sumatra, which triggered a tsunami event, appears to have decimated the ports in the northern Melaka Straits. This likely led to a further rise in prosperity in the ports located in the southern Melaka Straits, including Singapore.

This late-13th-century autonomous Singapore began when a prince from Palembang, the erstwhile capital of Srivijaya, left his homeland with an entourage and established a new port city in Singapore.

In order to attract Chinese traders, it made three locally-sourced Southeast Asian products, which Chinese traders were particularly keen on, available for export: lakawood incense, hornbill casques and redwood timber. It also differentiated itself from other suppliers in the region by offering these products at uniquely high quality.

|

| Present day Chinatown in Singapore during the Chinese New Year. |

In return, Singapore imported Chinese manufactured goods such as ceramics, iron wares, and textiles, none of which could be produced in the region because of the lack of technical know-how.

Archaeological research has shown that many of these imports were redistributed to the islands in the vicinity of Singapore.

Economic transactions were facilitated by the use of Chinese copper coins. Chinese currency facilitated trade not just with Chinese traders, but also with the regional power of Java, which operated a currency system based on Chinese coins.

A hierarchical economic relationship developed between Singapore, the people of the surrounding islands, and the regional and global economic powers of the day. These developments bolstered the political legitimacy of the rulers of Singapore.

The British Arrive

The second period of Singaporean autonomy began with the founding of a British East India Company (EIC) factory on the island in 1819 and lasted until the transfer of the island's administration to the Colonial Office in London in 1867. These decades saw the island administered by a Resident, who was appointed by the EIC office in Calcutta, but had to run the island completely on his own through revenue collected from the settlement's activities.

The island also developed an administrative system that relied entirely on prominent individuals and families resident in Singapore, who mobilized their social networks and communal leadership to make Singapore a functioning port city open to free trade.

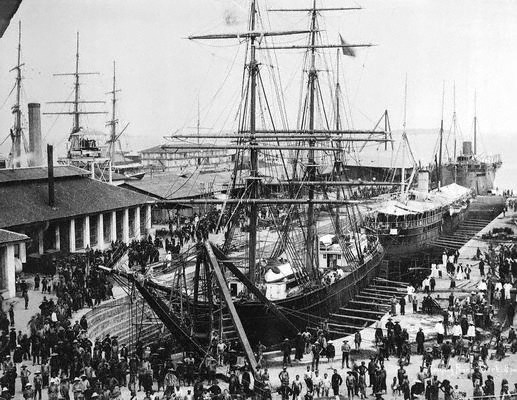

|

| A photograph of Victoria Dock, a British naval base in Singapore at Tanjong Pagar in the 1890s. |

As in the 13th century, global and regional factors may be observed in the founding and existence of Singapore as an EIC factory and autonomous port settlement.

Prior to the 19th century, the Dutch, under the aegis of the Dutch East India Company, had established and maintained economic and colonial supremacy over the Indonesian Archipelago for more than two centuries.

The British EIC, which initially tried to enter the Indonesian Archipelago market, was forcibly excluded from this region by the Dutch. Singapore, as a fief of the Johor Sultanate, played an inconsequential part in the larger regional geopolitics of this period.

However, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic wars of the late 18th and early 19th century shifted the global power balance and launched Britain’s ascent to the most powerful state in Europe and the largest colonial power in the world by 1815.

During that war, Dutch colonial holdings in the Indonesian Archipelago were temporarily ceded to the British for safekeeping as Holland fell under the onslaught of Napoleon's forces. The result was that British interests in the islands of Southeast Asia were rekindled.

Britain's trade with China was also growing. The British EIC’s factory was founded in Singapore to re-establish British interests in Southeast Asia, and to facilitate trade with China.

Like the changes that took place in global economic patterns in the 12th to 14th centuries, the geopolitical changes of the late 18th and early 19th century provided a window of opportunity for Singapore to transform from a marginal settlement in some larger political state to an autonomous economic center.

Like the changes that took place in global economic patterns in the 12th to 14th centuries, the geopolitical changes of the late 18th and early 19th century provided a window of opportunity for Singapore to transform from a marginal settlement in some larger political state to an autonomous economic center.

The primary movers in the founding of Singapore were private British merchants engaged in regional trade in Southeast Asia, and especially the lucrative opium trade with China, which the EIC did not engage in. In 1819, unknown to the Calcutta office and the company directors in London, the EIC factory was established by Sir Stamford Raffles (left) on behalf of the company.

The slow speed of communications in the 19th century resulted in the London EIC headquarters being informed of Singapore only a year and a half later. It reacted negatively to the news.

However, by the time company agents arrived in Singapore in 1821 to shut the settlement down, they found a population of 20,000, including merchants who had emigrated from as far as Thailand and Java, bringing their commercial networks and capital with them.

The signing of the 1824 Anglo-Dutch Treaty recognized Singapore as the southernmost extent of the British sphere of influence in Asia. Singapore was allowed to continue to exist within the British Empire, as long as it took care of itself and its bills. This the port city successfully handled until 1867, when it was transferred to be administered directly by London.

By that time, Singapore had grown from a small outpost into the center of the British Far East.

The British Forward Movement of 1874 saw Britain systematically formalize its administration over the Malay Peninsula in an effort to prevent German imperial desires from gaining a foothold in that part of Asia. Singapore became the administrative center of this part of the British Far East, known as Malaya.

Capital investments poured into Malaya to finance the extraction of tin and oil and the cultivation of rubber. Singapore became the chief processing center and global export hub of these important commodities.

By the eve of World War II, Singapore had become the home of the international rubber exchange and the largest tin smelting center in the world, a major exporter of crude oil, one of the busiest ports in the world, and home to the largest British military base east of the Suez.

All of this growth, however, was premised on Singapore’s role within the British Empire and Malaya. By the 1950s, the effects of World War II on Britain and changes in international politics began to erode Singapore's achievements.

Singapore in the Postwar World

The postwar era was a time of dramatic change in the world, including the decline of Britain’s global power. The United Nations Charter of 1945 recognized the sovereign equality of all nations as the basis of international cooperation and security.

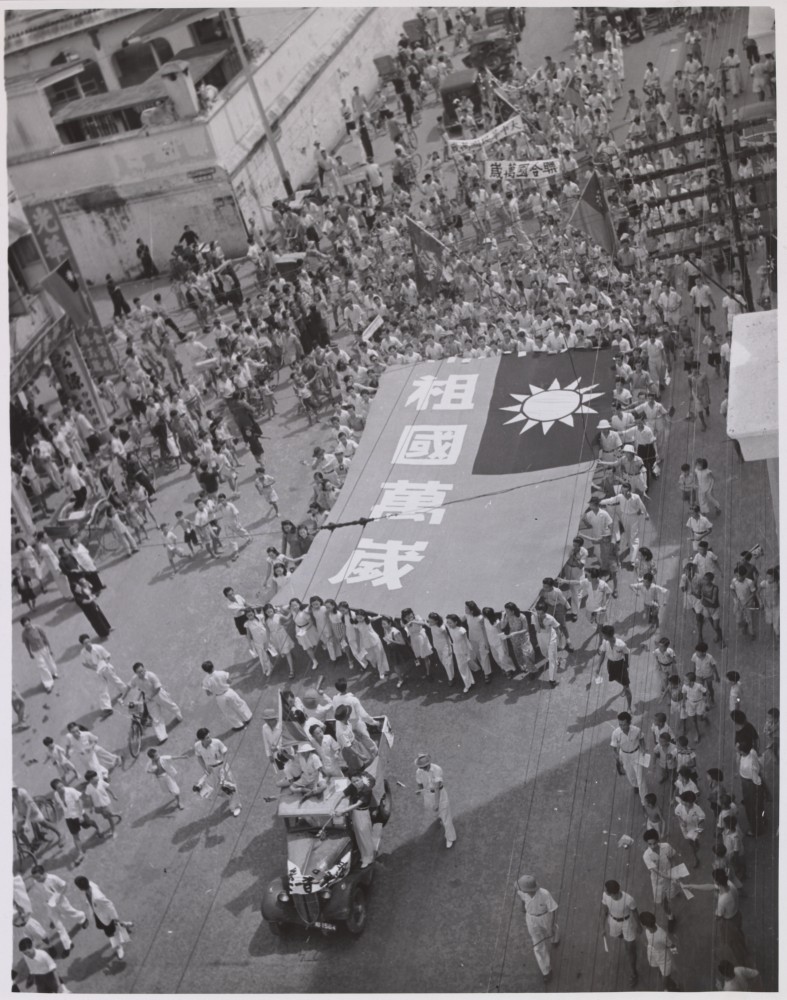

|

| Singapore's Chinese community carries the flag of the Republic of China that reads "Long Live the Motherland" in 1945. |

The advent of the Cold War saw the United States begin to systematically engage the Asia-Pacific region as part of its grand strategy in confronting the Soviet Union. After 1949, China grew increasingly insular.

This new American-led global framework was managed through the restructuring of the international currency system by the Bretton Woods Accords in 1958, which saw the U.S. dollar become the international currency of trade.

To ensure that the dollar maintained dominance over the global economy, economic barriers between countries outside the Communist bloc in Europe and Asia were systematically brought down through the 1947 General Agreement on Tariffs and trade (GATT), a precursor of the World Trade Organization.

By the 1960s, sovereignty was by and large guaranteed by the United States through key military and strategic alliances, coupled with bilateral economic ties and agreements.

Nonetheless, the British were still keen to maintain their management of the Malaya Peninsula through Singapore.

However, the 1956 Suez Crisis, which saw the United States opposed to the British invasion of Egypt, effectively terminated Britain's imperial desires worldwide. Global-scale decolonization was set in motion.

In Malaya, communist insurgents had been waging a guerrilla war against the British since 1948. While ethnic-based nationalist groups were promised internal self-government, the Suez Crisis set Malaya on the path to independence.

|

| A crowd of children cheers the return of the 5th Indian Division to Singapore in 1945. |

The logical conclusion, for representatives of the British government and nationalists in Malaya, was that Singapore would necessarily have to be a part of independent Malaya. Indeed negotiations with the British government specifically guaranteed Singapore’s place within Malaysia, the name of the soon-to-be-independent Malaya. This came to pass on August 31, 1963, when Malaysia was born.

Thus, Singapore did not in the first instance become an independent nation-state. It was transferred from one larger state to another.

The political center of this new country, however, was no longer to be in Singapore, as had been the case during British colonial rule, but in Kuala Lumpur.

Negotiations between Singapore’s political leaders, such as Lee Kuan Yew and Goh Keng Swee, and Malaysia’s Prime Minister Tungku Abdul Rahman, on Singapore’s continued central status and functions, were fraught with irreconcilable differences.

Eventually, following race riots and ideological quarrels, the Malaysian Parliament jettisoned Singapore from Malaysia on August 9, 1965. Independence was thrust upon the island and its people.

Independent Singapore

As a newly and unexpectedly independent nation in 1965, Singapore took advantage of shifting geo-political circumstances, especially in the Asia-Pacific region, to build a future for itself.

In Southeast Asia, the ideological conflict of the Cold War of the 1960s and 1970s resulted in the Vietnam War, the Cambodian civil war, instability in Indonesia, and immediate concerns that Thailand might succumb under the southward advance of the Bamboo Curtain, Asia’s equivalent of Europe’s Iron Curtain.

To safeguard its security against communist states in Asia and the potential of military incursions by Indonesia’s armed forces under the aegis of neo-nationalism, Singapore established armed forces along the Israeli model, enhanced its security arrangements with Britain, New Zealand, and Australia (under the Five Powers Defence Arrangement), and became a bilateral military ally of the United States. Singapore's Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew cultivated close diplomatic relations with Henry Kissinger during the Richard Nixon administration.

|

| Two ships in the Republic of Singapore's Navy, the RSS Steadfast and RSS Vigilance, sail alongside one another. |

To date, Singapore has remained one of Southeast Asia's major purchasers of U.S.- and Israeli-manufactured military equipment and weapon systems. It has a naval base that is capable of, and regularly hosts, U.S. aircraft carrier battle groups, and is home to several U.S. Air Force and Navy littoral combat units.

At the same time, the rehabilitation of Japan into an economic and military power as part of America's strategic framework in the 1950s and 1960s meant that Japan underwent an economic renaissance that saw an expansion of its manufacturing capabilities.

Japanese companies developed global chain-manufacturing systems, where different factories in the world would produce different components, which were then shipped to Japan for final assembly. The finished products were then dispatched to their final destination markets in the West.

This global system of product manufacture and assembly was made possible by the invention of the cargo container in 1958 and the international standardization of shipping containers in 1968, which led to a revolution in the global shipping industry. Mechanization began to replace human labor.

| The Port of Singapore is one of the largest and busiest container ports in the world. |

The launch of the Boeing 747 in 1970, which had two and a half times the carrying capacity of its largest predecessor and a cargo hold that was compatible with the international containerization system already developed for sea freight, provided a complementary high-speed logistics network with global potential.

Singapore benefited from all these developments.

The country’s strategic location between several key economies of the postwar era—Australia and New Zealand, Japan, the Indian Subcontinent, the Middle East, and Europe—helped make it a node for international trade, as under British rule during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In addition, the fact that the Melaka Straits remain the only channel between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, has meant Singapore was well placed to capitalize on the global containerization process, with the port of Singapore becoming central to the maritime shipping networks that connected the west coast of the United States to Asia, and onwards to Europe and the Middle East.

|

| The Jurong Industrial Estate was built in the 1960s and contributed to the industrialization of Singapore's economy. |

Logistics technology, the availability of global capital, and access to international markets meant that geographical constraints no longer determined economic survival and prosperity.

Once again, as in the fourteenth and early nineteenth centuries, regional factors played a decisive role in providing Singapore with the ability to maintain its newfound autonomy.

The convergence of all these developments presented Singapore with tremendous new economic opportunities. For Japanese companies seeking to build their supply chain manufacturing bases in Asia, the only viable locations were Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, and Hong Kong—all of which were not communist countries and which did not come under international trade sanctions.

Singapore's political leaders were presented with an economic and trade opportunity that they capitalized upon to great effect.

Singapore's political leaders were presented with an economic and trade opportunity that they capitalized upon to great effect.

These opportunities have also led to an emphasis to train Singapore’s political leaders in macro-economic skills. While technical education and the sciences have gained disproportionate attention and resources in its education system, a premium has been placed on macro-technical training for its top political and bureaucratic leadership. Singapore’s second and current prime ministers, Goh Chong Tong and Lee Hsien Loong (right), were both trained as macro-economists.

The country’s top scholarship holders, who are bonded to the Public Service Commission after graduation from their university studies, have consistently been encouraged to undertake technical or social scientific degree programs as opposed to programs in the humanities. It has only been in the past two decades that scholarships in the arts and humanities have been offered by the Singapore government.

Singapore Today

By the 1990s, Singapore had become listed by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) as an advanced economy, and was regarded as one of the four so-called Tiger Economies of Asia.

Nonetheless, economic development has brought with it new sociopolitical challenges. Chief among them is the inherent contradiction between the needs and dynamism of a nation-state, on one hand, and a global city on the other.

|

| A view of the Singapore River. |

Since the 1970s, the economic policy of Singapore, which has been based primarily on attracting foreign direct investments by multi-national corporations, has resulted in a very open foreign labor policy. While economic success and innovation has meant that doors are kept open to the flow of international talent and capital, Singapore’s nationalists have increasingly demanded that Singaporeans be given first priority in economic and education opportunities.

In recent years, qualification requirements for foreign worker permits have been raised, while the ratio of unskilled foreign workers to Singaporean workers in any business, with the exception of construction, has been capped at 1:3. Certain sectors hitherto reliant on foreign labor, have undertaken deep restructuring.

| The West end of Bukit Batok, one of Singapore's large-scale housing projects. |

Singapore's government has pushed forward with the goal of developing the country as the world's leader in widespread and fast internet access. However, these goals of connectivity have produced tensions internally. These media platforms have been used internally both by political parties and civic groups as a means of galvanizing ground support and social dissent against government policies.

China has now emerged as the major competitor to the United States in shaping economic and military policies in the region. These include benign initiatives, such as the establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, and more aggressive ones, such as the reclamation works in the South China Sea, where various Southeast Asian countries have laid claim to parts of this important maritime zone. With the recent violations of the territorial integrity of smaller states in other parts of the world, it is not clear what impact a resurgent and increasingly assertive China would have for smaller states in Asia.

|

| Singapore's Marina Bay Sands building had the second highest construction cost in the world. |

Singapore's first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew once commented that city-states throughout history have had a very poor survival record. Global forces have long provided the context for city-states to emerge, while regional forces have provided the opportunity for autonomy to be sustained.

As the world and the Asia-Pacific traverse the 21st century, and as Singapore celebrates 50 years of independence, it is worth pondering whether Singapore will survive as an autonomous country in the upcoming 50 years, or whether it will return to its longer historical legacy as part of a larger regional entity.

Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng & Tan Tai Yong, Singapore, A 700-Year History; From Early Emporium To World City (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2009).

C. M. Turnbull, A History of Singapore, 1819- 1988 (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1989).

Gillian Koh & Ooi Giok-Ling (eds.), State-Society Relations in Singapore (Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies, Oxford University Press, 2000).

Derek Heng & Syed Muhd Khairudin Aljunied (eds.), Singapore in Global History (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2011).

Lee Kuan Yew, From Third World to First: The Singapore Story, 1965 – 2000 (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2000).

Chiang Hai Ding, A History of Straits Settlement Foreign Trade 1870 – 1915 (Singapore: National Museum Singapore, 1978).

Amitav Acharya, Singapore’s Foreign Policy; The Search For Regional Order (Singpore: World Scientific Publishing, 2008).

Khoo Kay Kim, Elinah Abdullah & Wan Meng Hao, Malays/Muslims In Singapore; Selected Readings in History, 1819 – 1965 (Selangor: Pelanduk Publications, 2006).

John N. Miksic, Singapore and The Silk Road of the Sea, 1300 – 1800 (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2013).

Peter Borschberg, The Singapore and Melaka Straits: Violence, Security and Diplomacy in the 17th Century (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2010).

Carl A. Trocki, Singapore: Wealth, Power and the Culture of Control (Abingdon: Routledge, 2006).

Michael Barr & Carl A. Trocki (eds.), Paths Not Taken: Political Pluralism in Post-War Singapore (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2008).

Hong Lysa & Huang Jianli, The Scripting of a National History: Singapore and Its Past (Singapore: National University of Singapore Press, 2008).