Given how often and how much we watch sports on a screen, it's hard to imagine a time when that wasn't true. This month, historian Marc Horger traces the way in which live sporting events shaped the emergence of television, and how television shaped the emergence of big-time and big-money sports.

Contemporary televised sport, in many ways, has become a better fan experience than being there live. You get a perfect view of the action at all times; you get stats and replays; you avoid crowds, lines, traffic jams, bad weather, and bad vibes.

Even if you do crave a collective fan experience, you can get that at a sports bar, probably with better food at lower prices. At some stadiums, even if you are there live, you still might wind up watching the action on a giant screen.

Television’s symbiotic relationship with live sport has long been central to the business of each, and has grown more so as other forms of broadcast content lose out to streaming on demand. But the early relationship between the two was more ambivalent.

The technological limitations of early television impacted which sports could or could not be adequately conveyed on the small screen. Entrepreneurs in the business of luring people out of the house to spend money on live entertainment were wary of the long-term impact of a device that kept people at home.

It took a while for everyone involved to both achieve a small-screen experience comparable to being there and agree that doing so was in everyone’s best interest.

The Birth of Television and Televised Sport

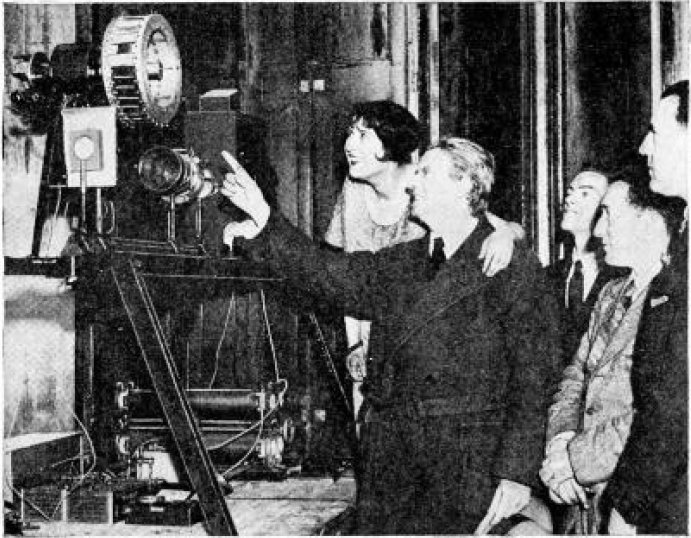

The technological ability to broadcast recognizable moving images through the air over long distances, synchronized with sound, is older than many people realize.

Examples of the successful transmission of images over a distance date to the 19th century. Public demonstration of moving images, transmitted in real time and synchronized with sound, date to the mid-1920s in a number of different countries, including the work of both Charles Francis Jenkins and Bell Laboratories in the U.S., John Logie Baird in the UK, and Kenjiro Takayanagi in Japan. The rudiments of what became television are therefore more or less the same age as sound film, The Jazz Singer having debuted in 1927.

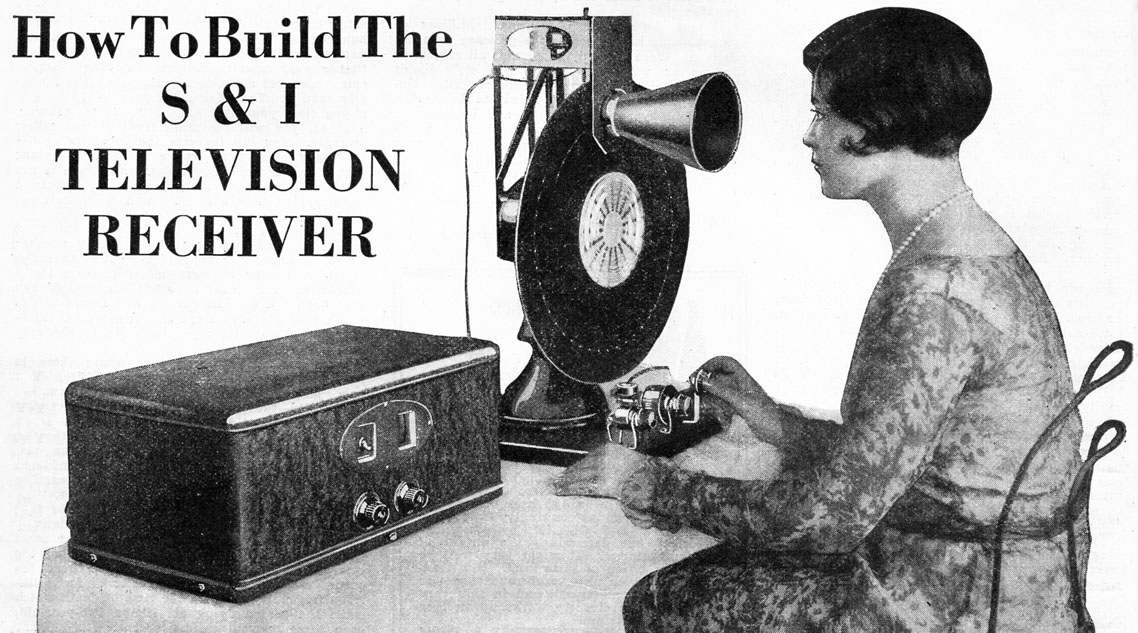

These early experimental broadcasts generated a transmissible image by scanning the scene with an analog device called a Nipkow disk. This rapidly spinning disk contained small perforations arranged in a spiral corresponding to the circumference of the disk, thereby breaking the image into what we would today call lines of resolution. A corresponding disc inside the receiving television reassembled the transmission into a viewable image.

This system, sometimes referred to as mechanical television, produced images of low resolution – often less than 100 lines in the earliest broadcasts. The content of a lot of these early broadcasts was therefore rudimentary and ad-hoc.

The audience, such as it was, much like the earliest radio audience a decade earlier, was entertained by the fact of television as much as by the content of television. Early experimental broadcasts therefore consisted of a patchwork of light entertainments, not unlike vaudeville, and a small audience of hobbyists and ultra-early adopters.

Nevertheless, evangelists for the new technology predicted almost from the beginning that it would, among other things, revolutionize the consumption of live sport.

The technological limitations of mechanical television, however, meant that this forecast took a long time to realize. In the United States, in fact, the earliest attempts to televise sport did not actually involve televising live sporting events, but staging simulations.

For instance, in 1931 station W2XAB in New York (later WCBS) broadcast weekly Exhibition Boxing Bouts, 15 to 30 minutes of simulated, miniaturized “boxing” contests staged especially for the purpose of broadcasting. Also in 1931, W2XAB created television simulcasts of college football by synching their ordinary radio coverage with visuals of, as the New York Times described it, “A Football Made of Tin”:

“A small football cut from sheet tin and painted white is moved by invisible wires and magnets to various positions on the field, always in synchronization with the voice of the announcer which comes from the scene of the contest. Downs, scores and other details are flashed on the screen from other boards on which the scanner may be focused at will….”

‘This is the nearest we can come to projecting the actual game,” said William A. Schudt Jr., television director at W2XAB. “Just as soon as the apparatus is perfected by which we can give images and talking pictures right from the scene of the contest, we will attempt it.’”

The first serious attempt to televise a genuine sporting event in real time came in the UK in 1931, when John Logie Baird sought to televise the Derby Stakes over the BBC.

Baird had by this time developed a rotating-drum scanning system somewhat more sophisticated than the Nipkow disk, and he placed one inside a caravan located just before the finishing post. A mirror on the door of the caravan reflected the scene inside for scanning and broadcast as Cameronian flashed by, three quarters of a length ahead of Orpen, for the victory.

Perhaps 5,000 people saw the broadcast around the country, though they didn’t actually see much – perhaps a second or so of race action, in an awkward 7:3 aspect ratio, at 30 lines of resolution.

Baird and the BBC tried again the following year, with slightly more robust results.

This time, they prioritized producing a large image in a public setting. To that end, a large screen and reception apparatus were set up for 2,000 spectators at the Metropole Cinema in London, just across the street from Victoria Station. They saw April the Fifth finish just ahead of Dastur on a 10 x 8 ft screen in 90 lines of resolution, triple the definition of the previous year.

By this time, however, mechanically-generated television was gradually giving way to a new, higher-definition electronic broadcast technology based on the cathode ray tube and capable of generating images with several hundred lines of resolution.

By the time the BBC returned again to broadcasting live sport – Wimbledon in 1937 and the FA Cup final in 1938 – it was using the new technology which, with slight differences here and there, eventually became the broadcast standard around the world. By the late 1930s there were perhaps 20,000 to 25,000 television receivers in the UK.

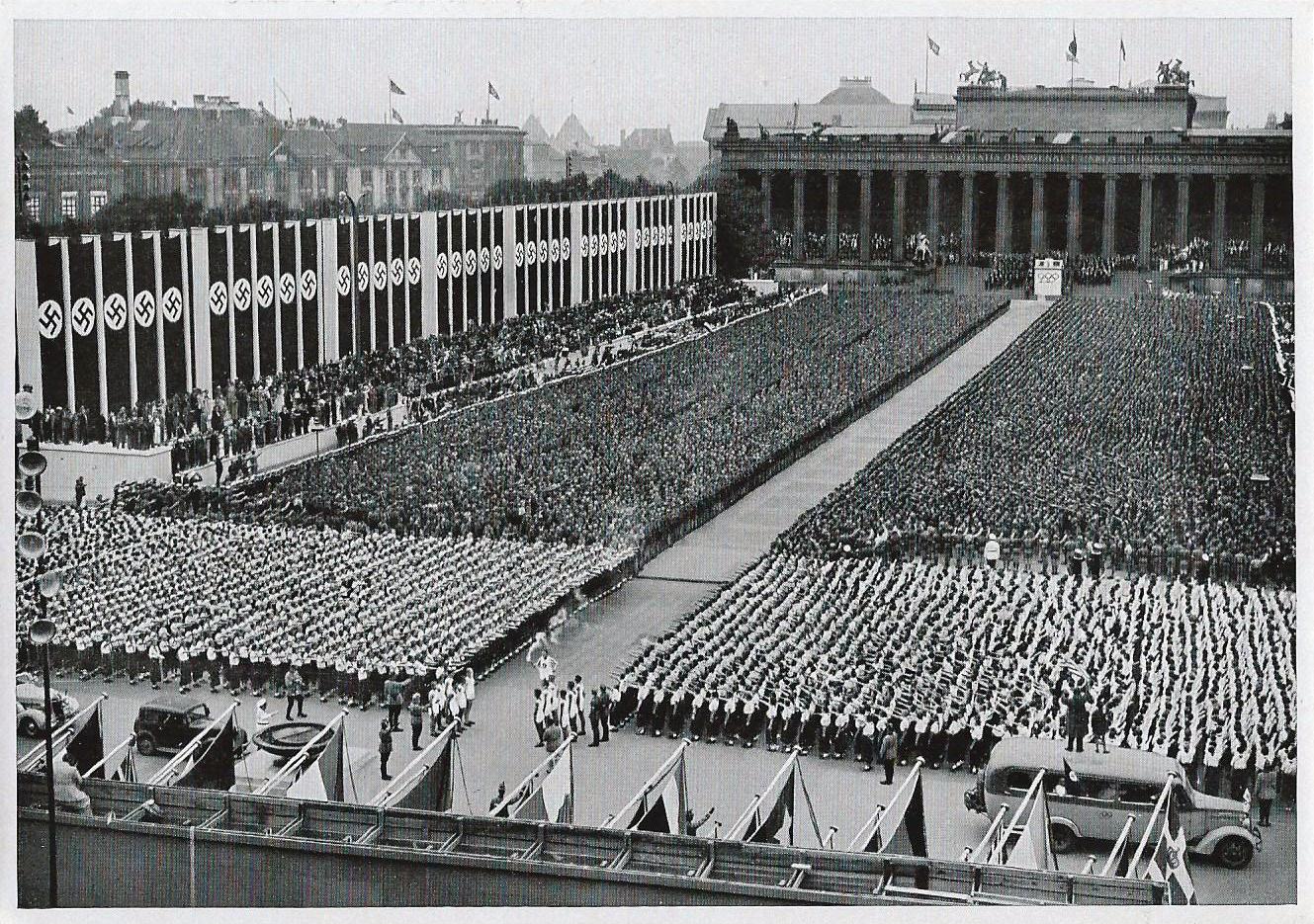

In Germany, television broadcasts were a central part of Nazi efforts to present the 1936 Summer Olympics to the world as an exemplar of alleged German technological modernity, an effort that also included live international coverage via short-wave radio broadcasts.

In an effort to maximize the reach of the new technology, the Nazis prioritized collective viewing, broadcasting several hours of coverage a day to dozens of collective “television rooms” – the equivalent of what would later be called closed-circuit venues – around the country. The official record of the 1936 Games claims that over 160,000 people saw at least some portion on television.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the transition from mechanical to electronic television was slowed by corporate rivalries among broadcasters, radio manufacturers, and patent holders.

As a result, fully realized electronic television didn’t become available to the public until 1939, when it premiered to much fanfare at the World’s Fair in New York. RCA, under the auspices of its broadcasting wing NBC, inaugurated regular commercial broadcasting with coverage of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt officially opening the fair, and CRT televisions began to appear in the marketplace.

By this time, American broadcast technology was prepared for live sport.

The first true sporting event to appear on U.S. airwaves was a college baseball game, Columbia vs. Princeton, from Baker Field at the northern tip of Manhattan, on May 17, 1939. A single camera captured a 2-1 Princeton victory.

On June 1, W2XBS (now WNBC) broadcast Lou Nova’s defeat of former heavyweight champion Max Baer from Yankee Stadium. Major league baseball first appeared on August 26, with Red Barber on the call from Ebbets Field in Brooklyn as the Dodgers split a doubleheader with the Cincinnati Reds, and a number of college and NFL football games appeared in the fall.

None of this early television survives – regular preservation of live TV broadcasts dates to after World War II, and even then the process used, the kinescope, was complicated and laborious. All existing sport footage from this era, even if eventually broadcast on television one way or another, was originally captured on film.

Mass Market Television and the Choice for Sport

At the onset of World War II, the United States was well behind the UK and a number of other countries in terms of television uptake. There were maybe a few thousand sets in the whole country, most of them in a handful of big cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Los Angeles. Radio remained the dominant broadcast technology.

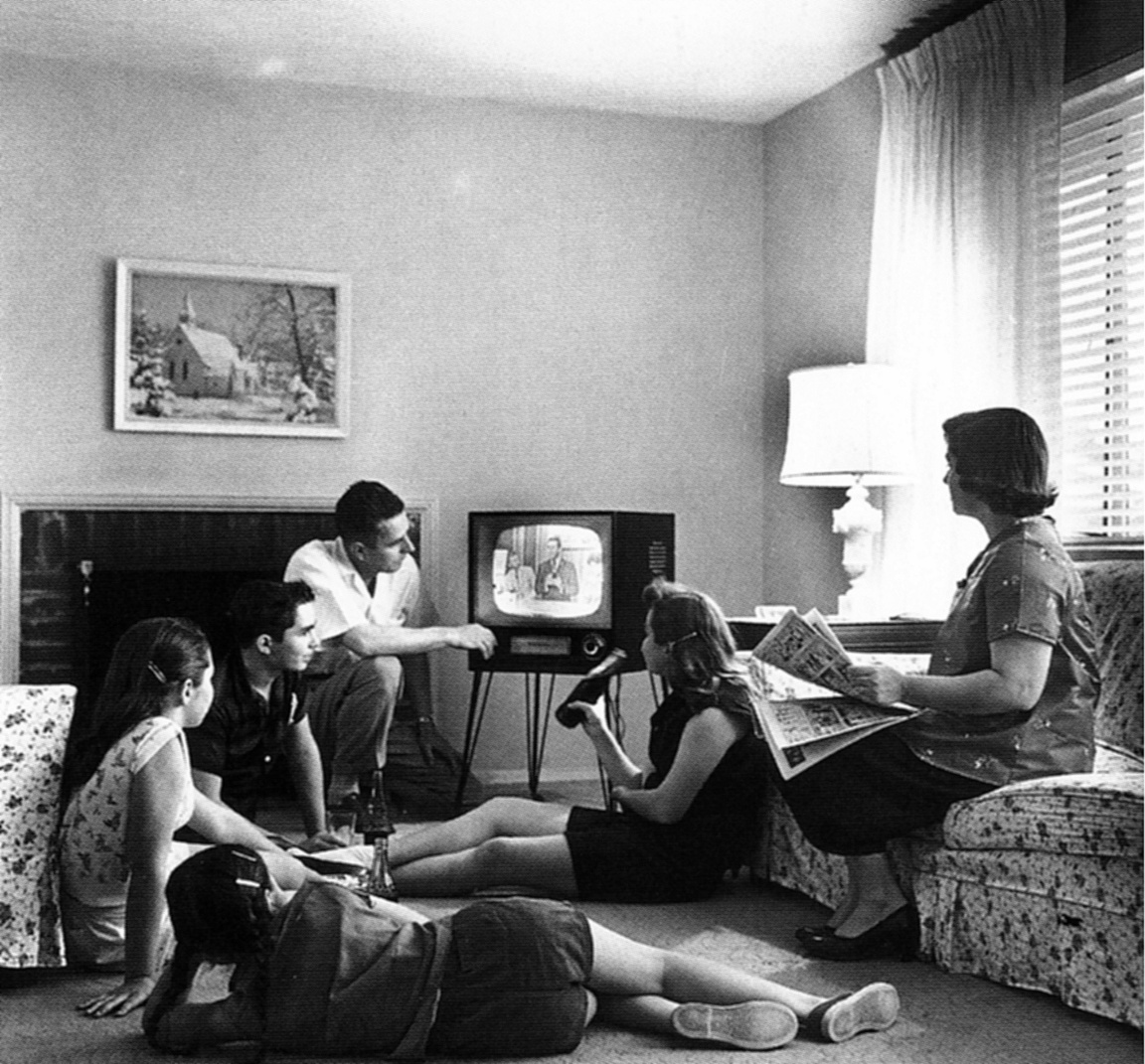

Explosive growth, however, came after the war; from a baseline of maybe 7,000 or so sets at the end of hostilities, televisions were selling at a rate of 200,000 a month by 1948, the year in which total televisions first passed a million units.

As television began finally to penetrate the mass market, people in the business of selling tickets of one kind or another had to decide if they regarded TV as a partner, a competitor, or something in between. Not everyone made the same choice.

The sport that developed the closest relationship with television the fastest was boxing. The reason was partly technological. Boxing was much easier to broadcast and much more satisfying to consume on the small screens of the day than most other sports.

One camera pointed at the ring was sufficient, both simpler and less expensive than the multi-camera setups and complicated production needed to make football or, especially, baseball compelling television. (Though not technically a sport, the same was nevertheless true of professional wrestling, another early programming success.)

Boxing and wrestling therefore became not just the most popular sports on postwar television, but among the most popular of all programming categories. By the early 1950s, boxing was on multiple nights a week, most famously the Gillette Cavalcade of Sports Fridays on NBC, mostly featuring fights from Madison Square Garden.

Television’s new relationship with MSG and a handful of other arenas contributed to shifts in the balance of power within boxing toward organized crime, which largely controlled access to the major arenas and, increasingly, managed enough fighters in enough weight classes to control much of the day-to-day promotion and management of the fight game.

Historians of boxing largely argue, however, that an additional consequence of the sport’s explosive popularity on television in the 1940s and 1950s was a long-term deterioration of its talent base: the network of small fight clubs and municipal arenas around the country that functioned as boxing’s minor leagues.

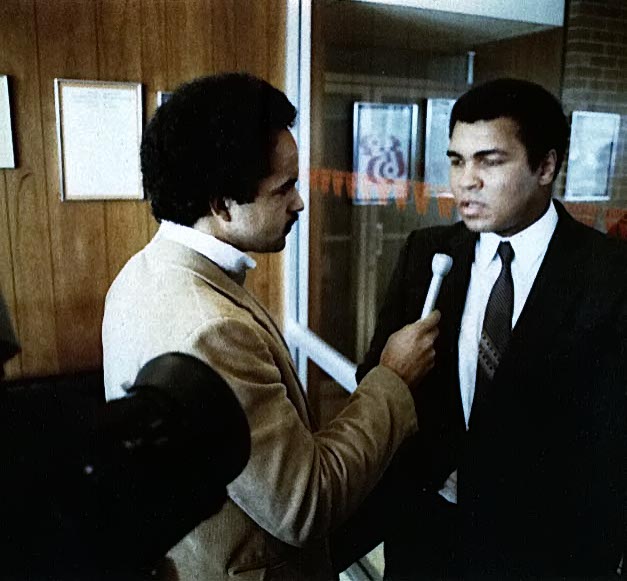

These had atrophied significantly by the 1960s, such that, while on the one hand Muhammad Ali was obviously one of the most important cultural figures in the world – in part because of how telegenic he was – he also represented the end point of heavyweight boxing’s centrality to American culture in the 20th century.

In college football, a few schools were eager to leverage television aggressively, most notably Penn, located in Philadelphia, a robust television market and home to Philco, one of the nation’s largest TV and radio manufacturers, and Notre Dame, which has always thought of its fan base as national rather than regional.

College Sports on the Small Screen

Penn had all of their home games on local television, with occasional exceptions during the war, as early as 1940, and Notre Dame found itself after the war fielding lucrative competing offers from multiple national networks as well as local channels in Chicago.

Most other schools were more ambivalent, however, unsure that the long-term financial impact would be net positive. Indeed, total college football attendance peaked in 1949 then began to decline, right around the time television began its breakout phase. The Big Ten in 1950 opted to ban its members from televising conference games, and many other schools proceeded cautiously.

In 1951, the NCAA inaugurated what turned out to be a generation-long era in which it, and not individual schools or conferences, would negotiate with the networks over how, and how much, college football would be televised.

The exact details varied from contract to contract, but the NCAA’s general approach was to offer a blend of nationally televised games and regional coverage, chosen with the intent of limiting both the damage to local attendance and the number of times a school could appear in any given year. Among the major football schools, only Penn and Notre Dame objected.

The NCAA’s embrace of television, however ambivalent in conception, nevertheless transformed the way Americans consumed football, in part because of technological and conceptual advancements in the televised product itself.

As the 1950s progressed, the game on the small screen grew more fluid as broadcasters developed more sophisticated ways to deploy and intercut multiple cameras. Schools gradually began to complain to the NCAA that they weren’t appearing on television enough. Even live attendance began to recover in the second half of the decade.

TV Transforms Baseball

Baseball approached television in a more haphazard fashion after the war, and as a result television mostly served to increase rather than decrease the relationship between size of local market – increasingly understood as size of media market, not just size of local population – and potential profitability.

With the exception of the World Series, All-Star Game, and a “Game of the Week” package on the weekends, baseball on TV was a local affair, negotiated by each individual club in the local media market. Even the game of the week contract paid out unevenly based on appearances, so more popular and/or successful teams benefitted more.

The winners were teams in major markets like the Yankees, which took to television early and aggressively in their local market and also dominated national broadcasting. The losers were the minor leagues, which experienced significant collective decline in attendance more or less in parallel with the rise of television.

Minor league attendance, like attendance at a lot of sporting events, peaked around 1949, when 49 million people cranked minor league turnstiles. By 1957, by which time television was more or less standard equipment in the American home, the number was 15 million; dozens of minor leagues had gone out of business entirely.

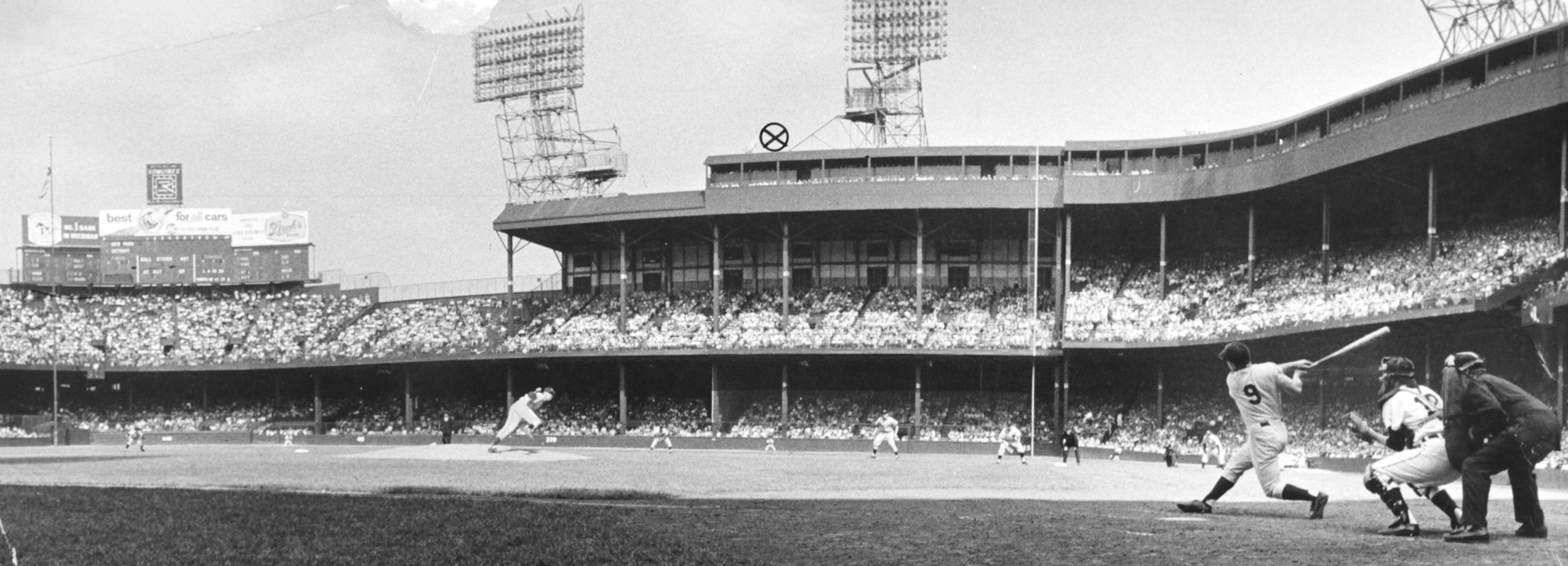

Baseball was ultimately the sport most transformed as a product by its technological translation onto the small screen.

What by the late 1950s became the standard visual grammar of the televised game – multiple camera views cut together live in real time, always focusing on the action from the best available angle – offered a view of the game impossible to achieve by any individual at the ballpark itself. Before the advent of the center field camera and the perfection of real-time camera cutting, only the shortstop came close to seeing the game the way the ordinary fan does today.

Football and the Business of Television

The sport most transformed as a business by its technological translation onto the small screen, however, was the NFL, which realized that television could be the core of their business rather than a threat to be mitigated and rode that realization to the hegemonic position it still occupies.

Before World War II, the NFL was widely considered of lesser importance not only to baseball and boxing, but also to college football. By the 1960s, it had overtaken them all. The pivot point was the 1958 NFL championship game, or more precisely the ratings for the 1958 NFL championship game.

The NFL’s initial postwar approach to television was tentative and experimental, not unlike some of the other efforts under discussion here.

In 1950, the Rams, recently moved to Los Angeles, televised all their home games with the provision that the sponsor, Admiral Television, would make up any loss in revenue at the gate relative to the previous year. The deal cost Admiral $307,000. The following year, only Rams road games were televised, and the gate rebounded.

The Chicago Bears in 1951 cobbled together a proprietary mini-network of ten stations across the Midwest, and lost money. The same year, the DuMont network began televising NFL games nationally, but itself went out of business five years later.

By this time, however, television had reached near-complete saturation of the market, and other networks had gradually transformed fall Sundays into a lucrative time slot.

CBS replaced DuMont as the NFL’s primary regular-season broadcast partner at a rate of $1 million a year; NBC held the rights to the championship game. It was therefore NBC that pulled in an audience of 45 million, despite the game being blacked out in the New York media market, when Johnny Unitas and the Baltimore Colts defeated the New York Giants 23-17 in the first-ever overtime championship game.

“THE BEST FOOTBALL GAME EVER PLAYED,” declared Sports Illustrated, and in front of the largest-ever audience.

By the 1960s, two additional things had occurred.

One, the NFL had a new commissioner, Pete Rozelle, committed to the idea that television, and media branding more broadly, was the core business the league was in, and furthermore that the value of the brand was collective. Under Rozelle’s leadership, the NFL moved away from individual contractual relationships between broadcast partners and each team and signed the first in a series of contracts with CBS for the whole of the NFL schedule as a package, with the revenue split evenly among the teams.

The contract contained blackout rules to partially protect the local gate, but, as the popularity of pro football soared in the 1960s and 1970s, the broadcast benefits were distributed evenly. The value increased from $4.65 million in 1962-3 to ten times that at the end of the decade.

Two, the NFL had a competitor, the AFL, which began play in 1960 and which signed similar network broadcast deals, first with ABC and then with NBC. By the mid-1960s, the two leagues were negotiating a merger, completed in 1970, which created the unified, nation-spanning NFL still with us today.

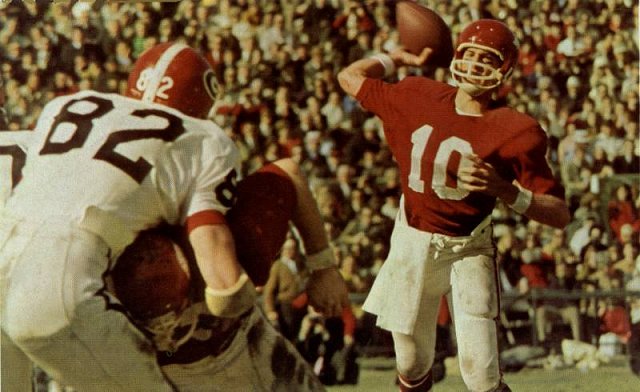

By this time, television was increasingly in color and the televised football product, including the collegiate product on ABC on Saturdays, was rich and sophisticated, capturing the atmosphere around the game as well as the action itself.

Today, the trend is toward everything being television all the time, including a Summer Olympics every second of which was streamable live, a new set of NBA media deals privileging digital partnerships over cable, and a global soccer marketplace open twelve months a year.

Yet at the same time, sport has also returned to the smallest of screens, given that a large smartphone or small tablet offers roughly the same viewing area as the 1939 RCA TRK-5.

Worthwhile histories of the earliest days of television include Joseph Udelson, The Great Television Race (University, Ala.: The University of Alabama Press, 1982) and Gary Edgerton, The Columbia History of American Television (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), each of which focuses on emerging technologies and efforts to commercialize them.

See also Philip W. Sewell, Television in the Age of Radio (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2014) and Anne-Katrin Weber, Television Before TV: New Media and Exhibition Culture in Europe and the USA, 1928–1939 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2022), each of which focuses on the emergence of ideas about how to employ the new technologies.

And Jeff Kisseloff, The Box: An Oral History of Television, 1920-1961 (New York: Viking, 1995).

For an account of early television’s long-term impact on American sport, see especially Benjamin Rader, In Its Own Image: How Television has Transformed Sport (New York: The Free Press, 1984) and Ronald Smith, Play-by-Play: Radio, Television, and Big-Time College Sport (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001).