It's March and that means March Madness! This month historian Sheldon Anderson argues that the real madness is not the annual NCAA basketball tournament but the NCAA itself. As he details, from its founding in 1910 the NCAA has exploited college students in the pursuit of ever greater profits. The whole system, he argues, has been broken from the beginning.

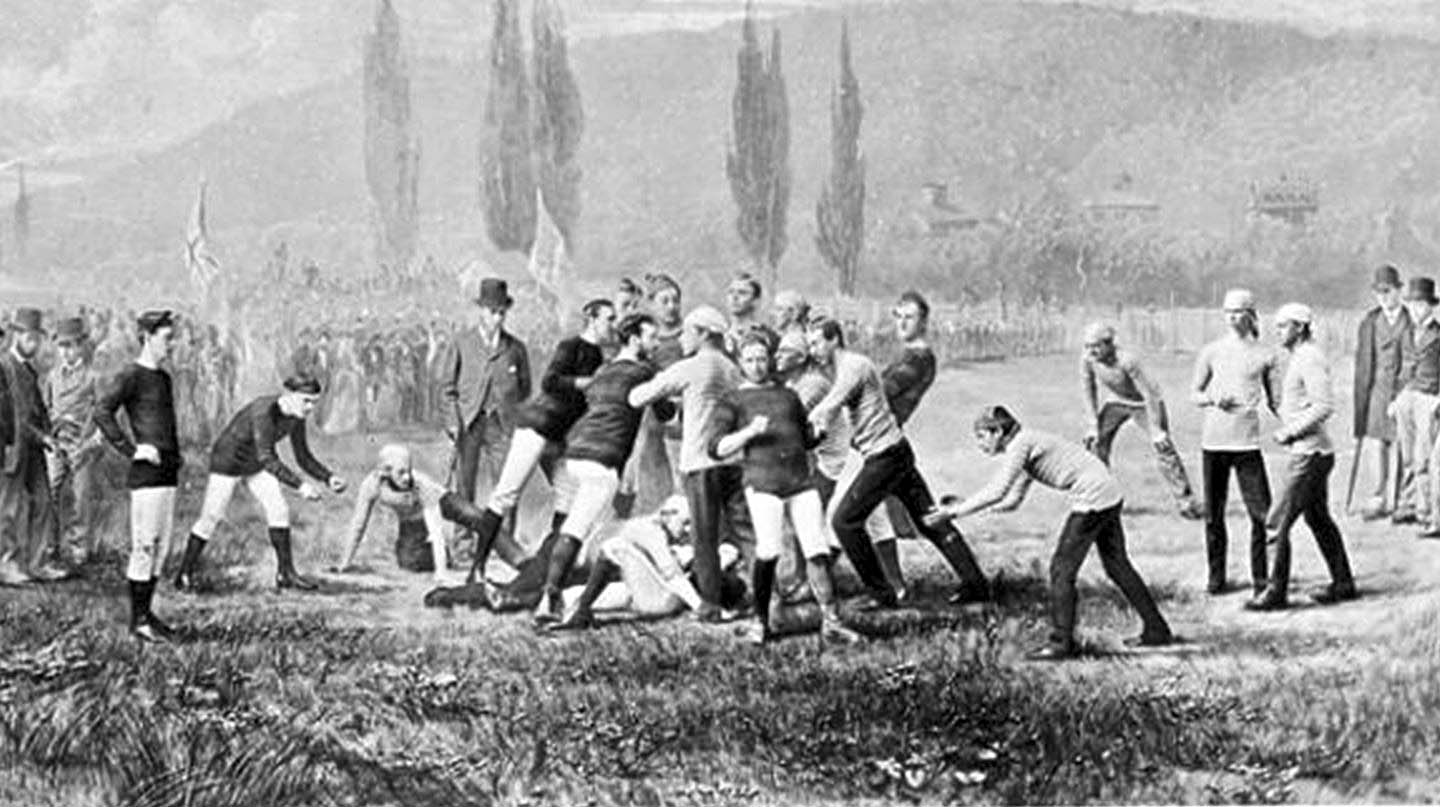

Intercollegiate sports had inauspicious beginnings.

The first college football game was played at Rutgers University in the fall of 1869. The home team trounced Princeton six games to four (every score was considered one “game”). The teams had 25 players a side, and to the 100-odd spectators the contest looked more like rugby. Undoubtedly friendly wagers were made among the fans, but the game itself made no money.

Men’s college basketball commenced with a similarly obscure contest.

In 1895 at Hamline University in St. Paul, Minnesota, athletic director Raymond Kaighn, who had played in James Naismith’s first basketball games in Springfield, organized a game against the Minnesota State School of Agriculture. Each team had nine players on the court and dribbling was prohibited. Minnesota won the high scoring affair 9-3.

Those quaint contests between neighboring colleges have grown into what Allen Sanderson and John Siegfried have called the “accidental industry”—the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)’s multi-billion-dollar business of intercollegiate sports.

In 2018-19, a century and a half after that first Rutgers game, the top six football bowl games and the national football championship made a nifty $549 million for the teams and their conferences.

Division I men’s basketball is the other big NCAA money-maker. Almost 125 years after the first game, NCAA revenue from the 2019 March Madness basketball tournament reached nearly $1 billion.

Players in those games got none of that cash. The reason for that, of course, is the NCAA.

The NCAA purports to be the last bastion of amateurism in the sports entertainment business. Only in the United States do big-time sports have a close connection to institutions of higher learning, where athletes are required to pose as college students. Every other major sport that began with amateur rules—such as soccer, rugby, tennis, and the Olympics—has gone professional and now pay players their fair share of the profits.

Still, the NCAA continues to defend its anachronistic, faux amateur structure.

Broken From the Beginning

What is remarkable about the history of intercollegiate sports is how little has changed. The corruption of the amateur ideal began at its inception and continues to this day.

As intercollegiate athletics became more popular in the late nineteenth century, universities began to use “ringers” to win games. It was common practice for colleges to enroll baseball players, sometimes under aliases, who had played in professional summer leagues.

The screenwriters of the Marx Brothers comedy Horse Feathers (1932) obviously knew that phony students were infiltrating college football. Professor Wagstaff (Groucho) wanted to enlist professional football players to help Huxley College beat archrival Darwin. (Wagstaff mistakenly hires a couple of bootleggers instead, and the usual mayhem ensues.)

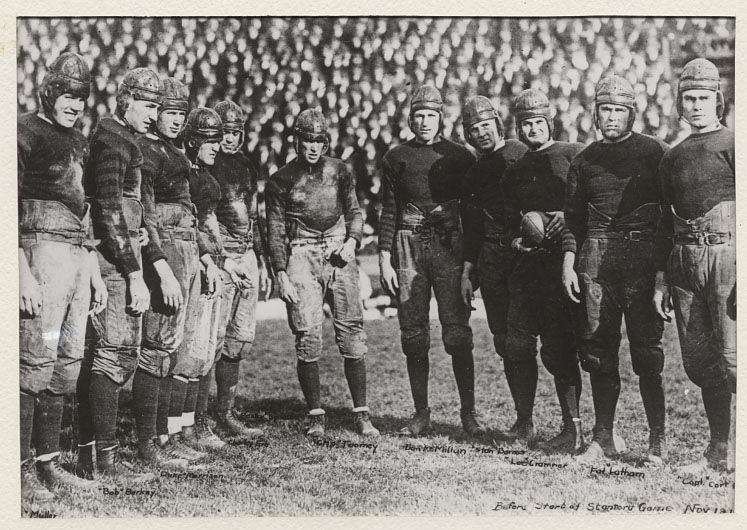

It was in a context of ringers and violence that the NCAA was founded. When at least 18 college football players died and as many as 168 were seriously injured during the 1905 season (according to the Cincinnati Commercial Tribune), the Intercollegiate Athletic Association (IAA) was formed to end the mayhem and bring an end to the corrupting influence of money in the game.

The IAA was renamed the NCAA in 1910, but the organization could not put the greenback genie back in the bottle. Universities ignored the NCAA and its rules, and they have regularly done so since.

College football boomed after World War I, rivalling baseball, boxing, and horse racing as America’s favorite sports. The big business of college sports encouraged cheating. “I am convinced, and reasonably so,” said Father Patrick J. Mahan, Creighton University president, “that no regular player is on a ‘big team’ without being paid. He does not, out of his own pocket pay for his tuition fees, board and lodgings. Yet authorities of universities decry the subsidizing of athletics.”

L.C. Boles, the athletic director and football coach at Wooster College (Ohio), implored “influential alumni, trustees, and curb-stone coaches” to exert pressure to reform the college game. Speaking to a gathering of physical education departments, Boles said that a sportswriter had it exactly right that college football was “one of the last strongholds of old-fashioned American hypocrisy.”

Boles added that “true educators” could not back college athletic departments “if we are sheltering hypocrisy, pseudo-amateurism or any shady practices.” Few cared. For a few schools, football subsidized all other athletic programs. In 1931 Big Ten football teams made on average $100,000 per school (nearly $2 million in 2022).

The huge new venues that were built for the lucrative college football franchises also contradicted the mythical amateur system. Yale finished its 70,000-seat stadium in 1914, the first of the big stadia on college campuses. The Los Angeles Coliseum was built in 1923, where nearby University of South California (USC) played football.

As early as 1926 the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) decried the detrimental impact of college sports on higher education: “The distortion of values lasts throughout the college course [the students’ years in college], if not through life.” The huge spending on stadia, the organization charged, “dwarfs the significance of the library, laboratory, and lecture hall.”

A 1929 Carnegie Foundation study concluded that big football was undermining the ethics and integrity of higher education, which were “of secondary importance to winning and financial success.”

Former Columbia University student Reed Harris published King Football: The Vulgarization of the American College (1932), in which he wrote, “Watching college football from inside and out has convinced me that the ‘grand old game’ has become a Frankenstein, threatening to throttle what is left of American higher education.”

A century later, athletics continues to grow at the expense of the educational mission. Administrators have decided that the best way to promote a university is to field winning men’s basketball and football teams, rather than on the excellence of their academic programs.

Only about 20 university athletic departments make a profit. The multi-million-dollar deficits run by the vast majority of D-I athletic departments are covered by the general education budget and student fees. The money spent on sports reduces the outlays for academics, including academic scholarships. At the same time athletic budgets increase, better paid tenure-track professors are becoming an endangered species, replaced by poorly compensated, short-term contract, adjunct, and visiting professors.

Employees Who Don’t Get Paid

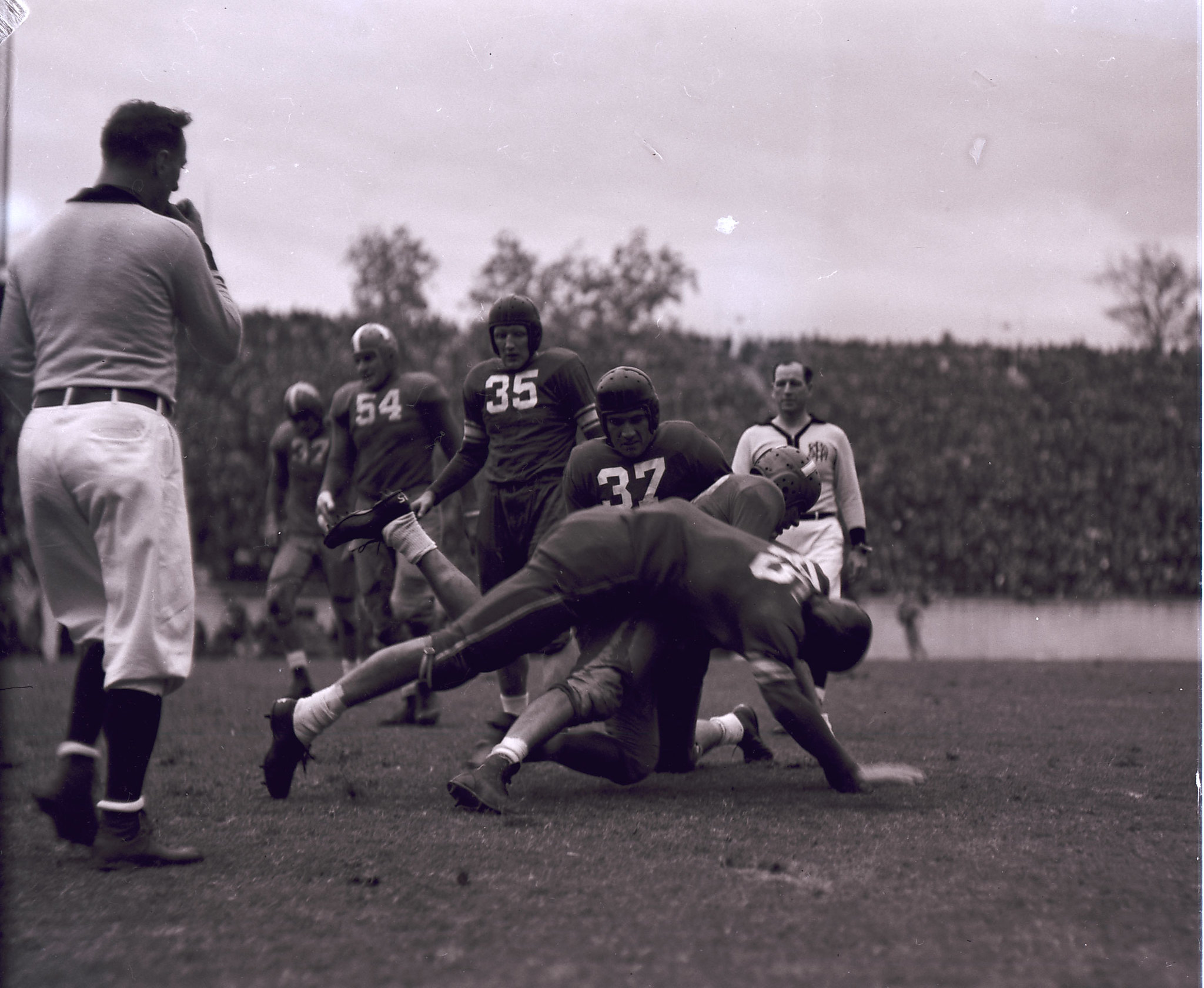

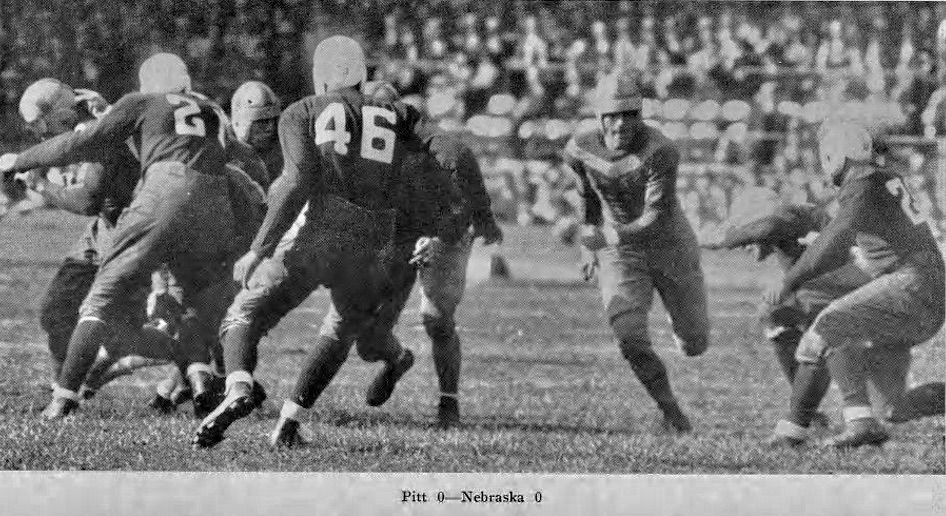

For over a century, the NCAA has maintained the illusion that college athletes do not receive cash payments. But it was obvious that players were being paid. University of Pittsburgh football players were pocketing up to $650 a year in the early 1930s.

Popular reporter Westbrook Pegler wrote that the practice should be brought out into the open. “[The problem was] the pretense and concealment, couched in resolutions and agreements of the most elaborate amateur piety.” The AAUP called the illegal payments to players “the crudest form of dishonesty.”

But this fiction is important. To keep profits for themselves, athletic departments, coaches, and the NCAA have doggedly clung to the legal definition of the athlete as a student and not an employee, even though everyone knows that if a player is good, his academic performance is irrelevant.

The free market imperatives of the business world, where the bottom line often trumps ethical behavior and fair treatment of workers, permeates the NCAA system.

In 1955 Ray H. Dennison died after sustaining a head blow while playing football for Fort Lewis A&M, a small school in Colorado. His widow sued the NCAA for workers’ compensation, but the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that the college was “not in the football business.” The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, where the NCAA won on the basis that Dennison was not playing for pay.

In 1960 Cal State Poly player Edward Gary van Horn was killed in a crash of a university plane. The university refused to pay any compensation to his wife arguing that his scholarship was a gift, not an employee’s wages.

In 1974 TCU running back Kent Waldrep was paralyzed from the neck down in a game against Alabama. Nearly two decades later, the Texas Workers’ Compensation Commission ruled that Waldrep was an employee of the university and was awarded $70 a week for life. The university’s insurance company appealed that a scholarship player was not an employee.

After years of litigation, in 2000 an appeals court handed down the final verdict: “[Waldrep] was not an employee because he had not paid taxes on financial aid that he could have kept even if he quit football.” School officials told Waldrep that “they recruited me as a student, not an athlete.” Waldrep called that “absurd.” Waldrep’s weekly seventy bucks were taken away, and he died in 2022, having spent two-thirds of his life in a wheelchair.

In effect, TCU told Waldrep to fend for himself. “So we occupy a world of hypocritical half-measures,” observed journalist Steve Rushin. “We still end up in front of the TV, watching some sanctioned act of violence that wouldn’t be countenanced if there were a People for the Ethical Treatment of People.”

The court rulings confirmed the wisdom of Walter Byers, who led the NCAA from 1951 to 1987. Byers guided the organization and its members to unprecedented financial success, and his clever creation of the term “student-athlete” protected universities from workers’ compensation claims, or from paying state and federal taxes. Byers said that “[the term] was embedded in all NCAA rules and interpretations.”

After retiring as executive director in 1987, Byers’ conscience spoke. Like Dr. Frankenstein and his monster, Byers came to rue his creation that was tearing asunder the academic mission of higher education. “The colleges have expanded their control of athletes in the name of amateurism,” he wrote, “a modern-day misnomer for economic tyranny.”

The NCAA claims to “promote the opportunity for institutions and eligible student athletes to engage in fair competition,” but its rules are inherently antithetical to the American dedication to the free-market system. The black market always plays the role of corrective to government restrictions on the free exchange of goods and services. Byers estimated that almost a third of D-I schools were breaking the rules and that illegal payments to athletes were commonplace.

The NCAA as a (White) Boys Club?

As an organization that is linked to institutions of higher education, it might be expected that the NCAA would be more sympathetic to issues of racial and gender equity. Yet for nearly a century the NCAA fought to keep African Americans and women out of intercollegiate sports.

The history of college sports shows that its discrimination against African Americans on the playing field mirrored societal racism, and college sports even lagged behind other institutions in breaking the color line. The NCAA turned a blind eye to southern schools’ discriminating against Black athletes long after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954 and the civil rights legislation of the mid-1960s.

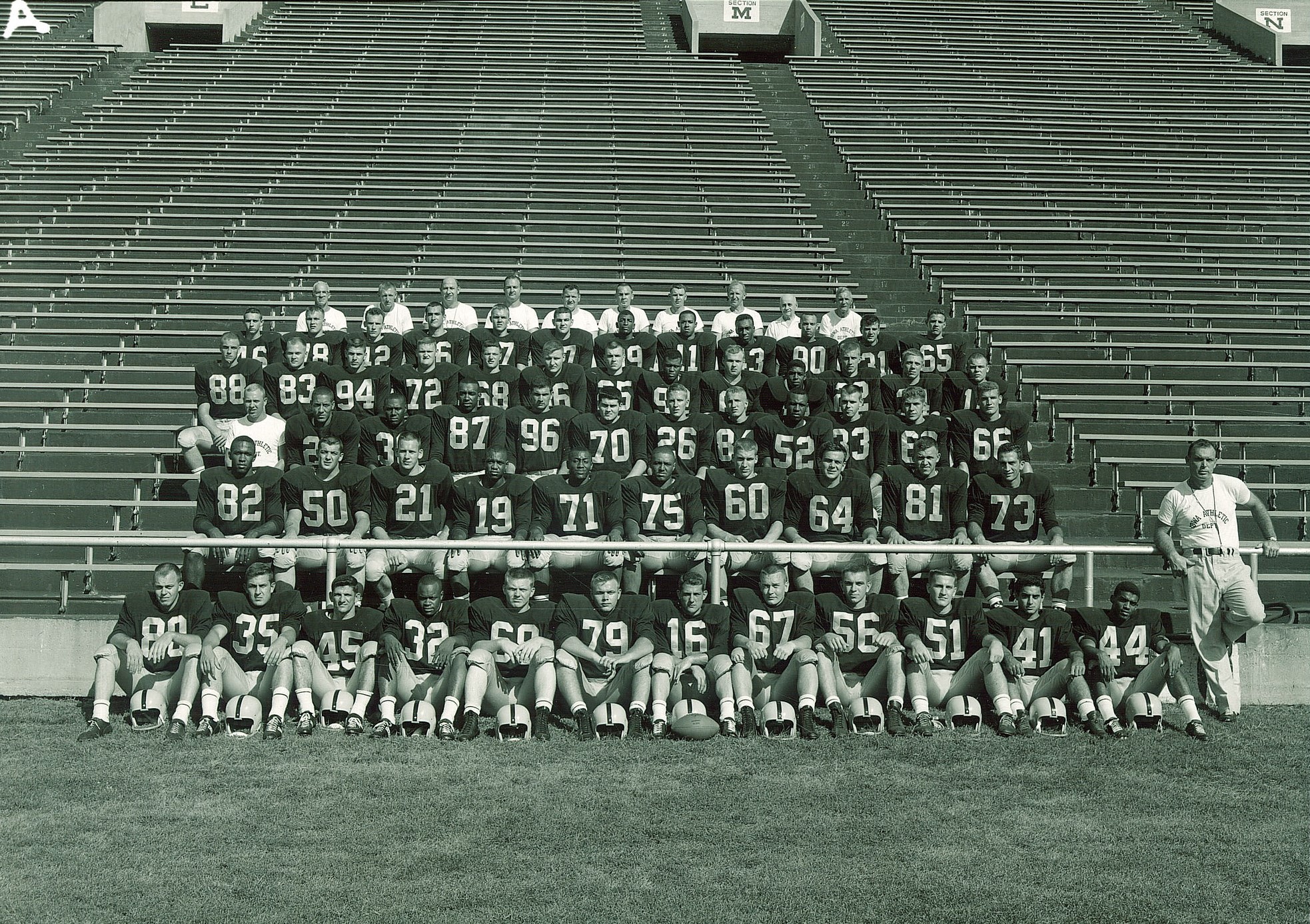

Southern schools such as Mississippi and Georgia were among the last to integrate their football teams in the 1960s.

“The most powerful force for integration [of college football in the south] was not high-minded principle,” charged historian Michael Oriard, “but the need to win football games, and integration, as future generations would learn, could mean recruiting ill-prepared young athletes with slight prospects of graduating. Opportunity and exploitation became deeply entangled.”

College coaches as a whole have not been interested in the intellectual development of their African American athletes. It was not very long ago that Black athletes were largely excluded from the football’s “brain” positions—quarterback, center, and middle linebacker.

Ohio State football coach Woody Hayes did not have a Black starting quarterback until Cornelius Greene came to Columbus in 1972; he led the Buckeyes to three straight Big Ten titles and Rose Bowls. Greene lost one Big Ten game in three years as the Buckeye quarterback, smashing Hayes’s perception of the mental limitations of Black folks.

Hayes had won games for years without a Black quarterback, but as schools became more integrated and competition got tougher, coaching jobs depended more and more on wins and losses. Coaches began to recruit the best players in any position regardless of their ethnicity, or their preparation for academic work.

The integration of college sports did not happen because progressive educators wanted to give African Americans a shot at a college degree, but because coaches couldn’t compete without Black players on the field.

Today the Power Five athletic departments depend on D-I football and men’s basketball programs to help cover the deficits incurred by the rest of their athletic programs. The predominance of Black men in the two revenue-producing sports means that they subsidize sports such as women’s volleyball, soccer, lacrosse, gymnastics, softball, rowing, and equestrian, and men’s sports such as baseball, gymnastics, golf, lacrosse, and wrestling.

Rowing and equestrian are not equal opportunity sports. Except for track and field and women’s basketball, white athletes overwhelmingly dominate the non-revenue sports. As of 2015, non-white women made up over twenty-six percent of the college population, but only 17.5 percent of the women athletes.

“These are largely African American players that are being kept poor in order to enrich white athletic directors, coaches and sports company executives,” observed Connecticut Senator Chris Murphy in 2019. “There’s no other marketplace in the country in which the people providing the labor should be compensated millions of dollars and are instead being given no salary.”

Congress passed Title IX in 1972 to give women equal opportunities in collegiate sports. But just as civil rights legislation had passed in the mid-sixties in part because of Soviet criticism of Jim Crow, Title IX was driven by Soviet propaganda about the equal legal rights enjoyed by women in the USSR, as evidenced by the trouncing that U.S. women took at the hands of Soviet Olympic athletes.

After the passing of Title IX, the NCAA marginalized the rival Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (AIAW) and women’s control over their own sports. In the fifty years since the Title IX legislation, the number of women coaches at D-I schools has decreased by nearly half.

The NCAA and athletic directors have been railing against Title IX ever since it passed, especially at mid-major D-I schools that spend millions to provide the mandated equal numbers of athletic scholarships for women at publicly funded schools.

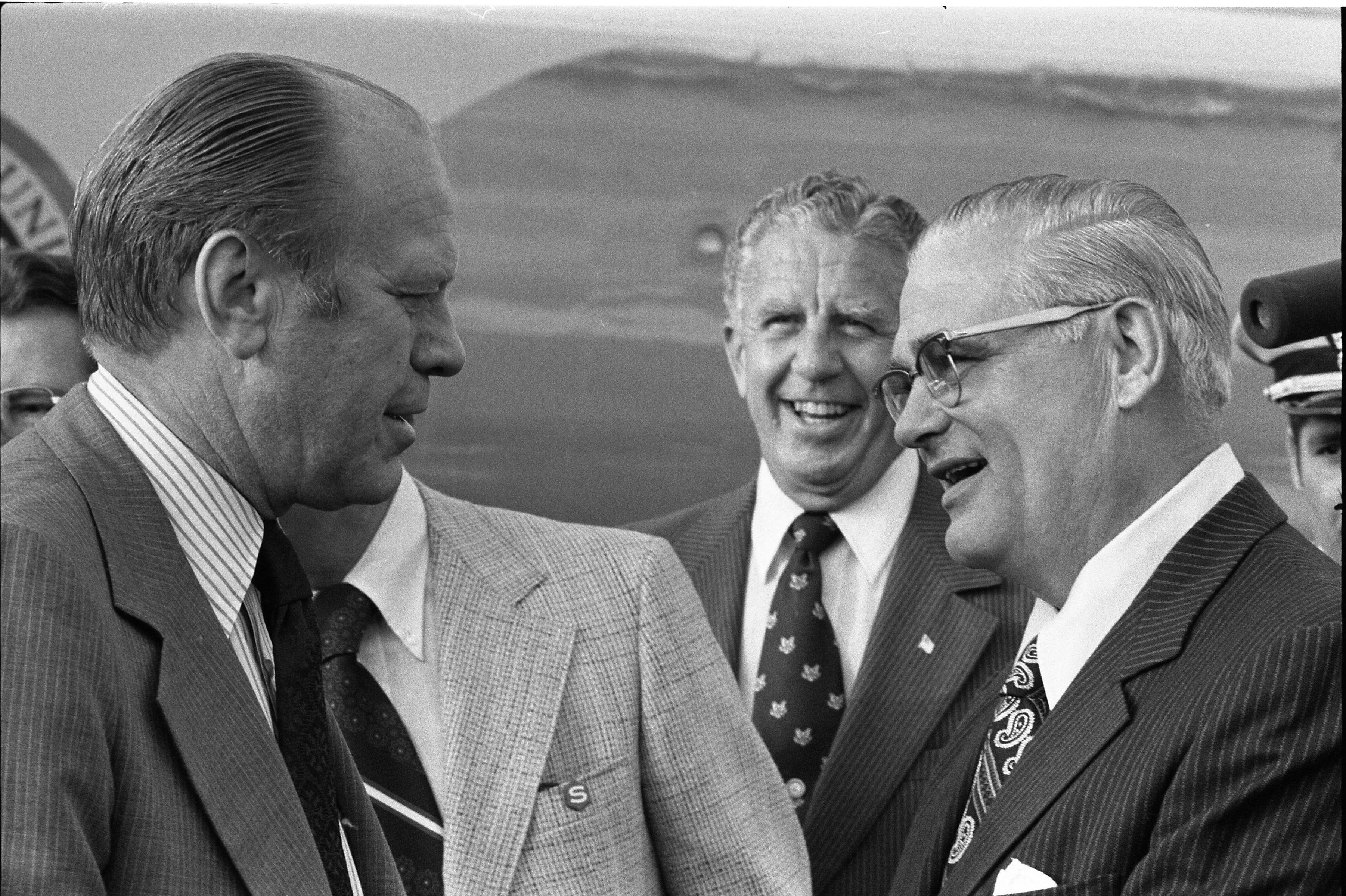

NCAA executive director Walter Byers predicted that Title IX might be the “possible doom of intercollegiate sports.” John Fuzak of the NCAA wrote Michigan representative Gerald Ford, “The HEW [Health, Education, and Welfare] concepts of Title IX as expressed could seriously damage if not destroy the major men’s intercollegiate athletic programs.”

Although progress has been made, the NCAA is still run by the good old boys who resent Title IX and that the profits from men’s sports have to be shared with women. This state of affairs came into full view during the 2021 NCAA men’s and women’s basketball tournaments. The men had access to fully equipped workout gyms, while the women got some light free weights.

According to one journalist, “[The women] received far less in their swag bag, and poorer food options. . . . The men were given even more reliable COVID tests.” Noted Washington Post columnist Sally Jenkins pulled no punches: “Sick and tired of the chiseling administrators with their million-dollar salaries and monstrous heaps of revenue who act like women’s basketball players should be thankful for a uniform that isn’t funded by a bake sale.”

Stanford head coach Tara VanDerveer concurred: “A lot of what we’ve seen this week is evidence of blatant sexism. . . . The message that is being sent to our female athletes is that you are not valued at the same level as your male counterparts.”

When the weight room discrepancy made the news, critics also pointed out that the men had 68 teams in their tournament, but the women only 64, and that NCAA paid for the men’s National Invitation Tournament (NIT), but not the women’s. The NCAA claims that the women’s NCAA tournament yields “no net revenue,” although nearly 80 companies sponsored TV ads for the 2021 tournament.

The NCAA combines its TV revenues and keeps its accounting hidden from view. “Part of the issue,” says financial analyst Daniel Rascher, “is that they blend the revenue from media deals. When you start pulling at threads, you find the NCAA has a highly flexible definition of ‘costs,’ amid a tangle of revenue streams, unallocated funds, resources and values-in-kind.”

The absence of hiring of women and minorities in college athletic administrations is glaring and very hard to justify. A vast majority of the Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS – the top half of the D-I schools) coaches are white, while most of their players are African American.

Athletic departments are also overwhelmingly white and male. In 2018 the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports at Central Florida State University studied the personnel of university leadership positions in the FBS that were directly or indirectly connected to sports, including presidents, athletic directors, football coaches, and conference commissioners.

The findings were damning: of 395 leadership positions included in the study, whites held 337, or about eighty-five percent. Whites held 62.5 percent of the assistant football coaching positions, while 54.2 of their players were Black. Richard Lapchick, the head of the institute and the report’s lead author, said that progress in diversity hiring has been “glacial.”

If college administrators were serious about diversity, they would insist on change; there are plenty of qualified women and Black candidates. But most of those administrators and athletic directors are white males, as are the boards of trustees and athletic boosters, who are reluctant to listen to any arguments about racial and gender equity. They are more comfortable with hiring athletic directors and coaches who look like them.

Few women are entrusted to run D-I athletic departments, although almost half of the athletes are women. “We’re talking about sports programs that are balanced by gender, roughly,” observes University of Pittsburgh’s chancellor Patrick D. Gallagher, “so I don’t see any reason why, in a world where we’re half women and half men, we shouldn’t see similar parity.”

As of 2019, Pitt’s Heather Lyke was one of only four women who headed the athletic department of the 65 colleges in the five biggest conferences (6.2 percent). In 2013, slightly over eight percent of all D-I athletic directors were women; six years later, women made up only eleven percent.

The NCAA in the 21st Century

The NCAA pays homage to a nineteenth-century amateur ideal while the organization runs a multi-billion-dollar sports industry with multi-million-dollar salaries paid to NCAA administrators, athletic directors, and coaches. Amateurism, such as it is and never was, is for the unpaid athletes only.

If athletes were scholars first and athletes (entertainers) second, athletic directors and coaches would be judged on the basis of graduation rates and athletes’ performance in the classroom. Lousy win-loss records would be irrelevant in the hiring and firing process. Of course, that is not the reality in which we find ourselves.

Reform of the current system seems impossible. Well over a century ago, college presidents and faculty recognized that intercollegiate athletic contests were undermining the mission of higher education and siphoning money away from academics. Reform efforts have repeatedly failed; the money in college sports has grown exponentially, in tandem with rule breaking. None of the stakeholders who make millions on big-time college sports have any incentive to change the system.

The only solution to the broken NCAA system is to create separate, stand-alone, self-financing clubs on campus, but with no connection to the university, administratively, financially, or academically. The teams will pay administrators, coaches, and players what their independent budgets will allow. The clubs will be run like a business, and players for the Duke Basketball Association or the Notre Dame Football Club, for example, will have the option to enroll in the university, and can play for the club as long as they want.

Recent court decisions have forced the NCAA to allow college athletes to sell their name, image, and likeness (NIL). It is only a matter of time before the NCAA goes the way of the other amateur-turned-professional sports. The sooner the better.

Murray Sperber highlighted the problems of NCAA sports in his groundbreaking book, College Sports Inc.: The Athletic Department vs the University (Henry Holt, 1990), and followed that up with Beer and Circus: How Big-Time College Sports is Crippling Undergraduate Education (Henry Holt, 2001).

Walter Byers, the former executive director of the NCAA and creator of the term “student-athlete,” was an important witness in Sperber’s case against D-I college sports. After retiring, Byers had a change of heart, bluntly stating in Unsportsmanlike Conduct: Exploiting College Athletes (Michigan, 1995) that “colleges have expanded their control of athletes in the name of amateurism – a modern-day misnomer for economic tyranny.”

History of Education professor John R. Thelin supplemented Sperber’s works in Games Colleges Play: Scandal and Reform in Intercollegiate Athletics (Johns Hopkins, 1994), a survey of history of intercollegiate athletes from its inception, citing the repeated scandals that have dogged the system.

Sports management professors Allen L. Sack and Ellen J. Staurowsky echoed Sperber’s and Thelin’s criticism of the NCAA in College Athletes for Hire: The Evolution and Legacy of the NCAA’s Amateur Myth (Praeger, 1998), as did economists Andrew S. Zimbalist in Unpaid Professionals (Princeton, 1999), and Charles Clotfelter in Big Time Sports in American Universities (Cambridge, 2011).

Another important work is John Sayle Watterson’s College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy (Johns Hopkins, 2000).

In Pay for Play: A History of Big-Time College Athletic Reform (Illinois, 2011), Ronald A. Smith explored the futile attempts to reform a college sports system that was broken from the start. Smith followed that up with the Myth of the Amateur: A History of College Athletic Scholarships (Texas, 2021).

Author Jeff Benedict and journalist Armen Keteyian tell the sad story of repeated football scandals in The System: The Glory and Scandal of Big-Time College Football (Doubleday, 2014).

New York Times columnist Joe Nocera and Washington Post reporter Ben Strauss, in Indentured: The Inside Story of the Rebellion Against the NCAA (Penguin, 2016), add other voices calling attention to the fiscal inequities in college sports.