In 2018, right-wing talking-head Laura Ingraham told basketball star LeBron James to "keep the political comments to yourselves [sic]" and told him to "shut up and dribble." The comments were intended to be insulting but they also betrayed a lack of historical understanding. Black athletes have always had to negotiate complicated political and racial issues, and this month historian Derrick White gives us a history of the racial politics of sports.

On May 6, 2020 NBA superstar LeBron James tweeted: We're literally hunted EVERYDAY/EVERYTIME we step foot outside the comfort of our homes! Can't even go for a damn jog man! Like WTF man are you kidding me?!?!?!?!?!? No man fr ARE YOU KIDDING ME!!!!!"

LeBron James in his Cleveland Cavaliers uniform, 2008.

James was reacting to a forty-second video released of three white men--a former police officer, his son, and a neighbor--hunting down Ahmaud Arbery while he was jogging in Brunswick, Georgia. The clip sparked national outrage, especially since the local police initially decided not to arrest the three men.

Other athletes also expressed their disgust. Former WNBA star and current University of South Carolina women's basketball coach Dawn Staley tweeted, "More senselessness. Video is heartbreaking. How many more mothers will have to bury their sons and daughters?! Answers needed. #AhmaudArbery.”

The tweets came amid a wave of anti-racist activism in the United States and around the world that responded to the murders of Arbery, Breonna Taylor in Louisville, and especially George Floyd in Minneapolis. Floyd’s murder prompted protests that were, by some accounts, the largest in world history. Demonstrations occurred in all fifty states and on every continent except Antarctica.

Floyd's murder also spurred athletes from social media commentary into action. Jaylen Brown of the Boston Celtics drove fifteen hours from Boston to join fellow NBA player Malcolm Brogdon in a protest in Atlanta. Sixteen-year-old tennis star Coco Gauff spoke at a rally in her hometown of Delray Beach, Florida.

College athletes led protests through their college towns, encouraging typically apolitical coaches to side with Black Lives Matter. Kylin Hill, star running back for Mississippi State University, announced that he would not play unless the Magnolia State removed the Confederate iconography from its flag. All-American women's basketball player Rhyne Howard and several other teammates led a protest across the University of Kentucky campus.

Contemporary Black athletes' participation in political rallies is just the latest example of athletic activism that stretches back over a century. In fact, prominent Black athletes have never been able to draw a neat separation between their sports and the larger political context in which they played those sports. To be a Black athlete in America has always meant confronting the politics of race.

The Rise of Jim Crow Sports

In the three-plus decades after the Civil War, Black athletes often had integrated sporting opportunities. For example, between 1875 and 1902, eleven African American jockeys, led by Isaac Murphy, won the Kentucky Derby.

Jockey Isaac Murphy in 1885 (left). Jockey Oliver Lewis, a black man from Kentucky, riding Aristides to victory in the inaugural Kentucky Derby, 1875 (right).

As Jim Crow and other forms of White supremacy took hold at the turn of the 20th century, the color line was drawn in sports too. Despite Murphy’s success, horse owners demanded white jockeys exclusively. White jockeys also excluded black riders from their union. In 1900, jockeys in New York conspired to exclude Black competitors.

Other sports followed a similar trajectory. Professional baseball, initially integrated, forced out its last African American player, Moses Fleetwood Walker, in 1889. “In no other profession has the color line been drawn more rigidly than in baseball,” wrote Sol White, an African American player for both integrated and segregated teams, in Sol White's Official Baseball Guide (1907).

When the National Football League was formed in 1920 it fielded integrated teams. That ended in 1933 when professional football became all-white.

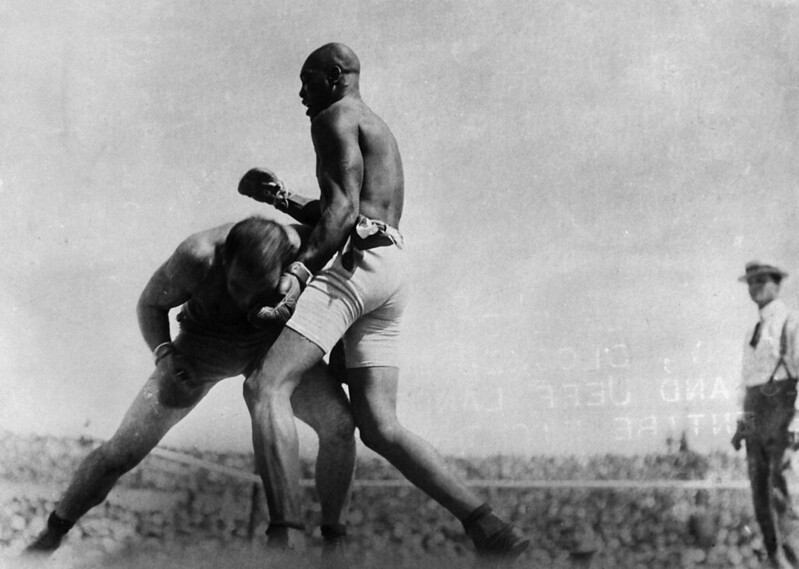

Jack Johnson (right) fights James J. Jeffries in 1910.

Heavyweight Jack Johnson was the most electrifying boxer of his generation and a lightning rod for racial controversy. Johnson held the heavyweight title from 1908 to 1915. But because of an informal agreement in the American sport to lock out Black fighters, he had to follow champion Tommy Burns to Australia, where the champ eventually agreed to fight for a purse of $30,000 (approximately $900,000 in 2021). Johnson won in 14 rounds.

Johnson was a flamboyant champion, regularly dressed in expensive clothes, drove flashy cars, and dated and married white women. Though he was not overtly political, his style, his defiance, and his refusal to abide by racial codes made him "The Black Menace” in the eyes of the white sporting public. The federal government arrested and prosecuted Johnson for violating the Mann Act, which forbade transporting women across state lines for prostitution, in 1912. Johnson fled the country, fighting overseas until he lost the title in 1915.

W.E.B. Du Bois recognized the hypocrisy surrounding Johnson. "We have yet to hear," he observed, "that marital troubles have disqualified [white] prizefighters or ball players or even statesmen. It comes down, then, after all to this unforgivable blackness.”

Black Sporting Institutions

During the Jim Crow era, African American sporting communities responded to racial exclusion by creating opportunities. At the collegiate level, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) developed an array of teams in men's and women's sports, developed their own athletic culture, and celebrated Black community traditions.

Sportswriter Eric "Ric" Roberts, who starred on the gridiron Clark College (now Clark Atlanta University) in the 1930s, recalled, "Our heaven and our glory was … not at Harvard, but Howard and Lincoln and it [moved] south where Morehouse and Atlanta University and Clark and Morris Brown and Tuskegee and Alabama State and finally Florida A&M and other schools west of the Mississippi … all joined the passion [of the] black world.”

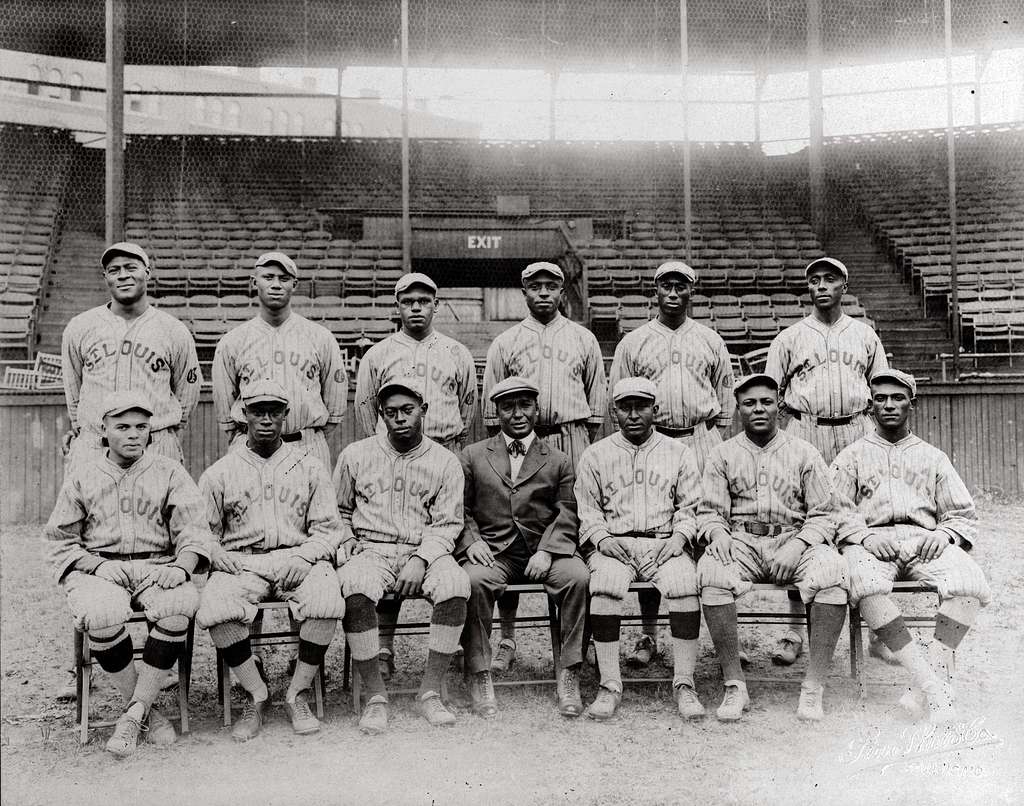

The St. Louis Giants, pictured in 1916, later became a team in the National Negro League.

Under the leadership of Rube Foster, Black baseball players plied their talents in the Negro National League (NNL) starting in 1920. Previously, African American teams barnstormed across the country searching for competition, bragging rights, and money. Without a league or association, this erratic schedule meant made it impossible to tell which was the best team in Black baseball.

Foster created the NNL to improve the quality of Black baseball. After a series of fits and starts, the Negro National League and the Negro American League, founded in 1937, developed a highly competitive league filled with players who were shut out of Major League Baseball.

Denied access to tennis and golf facilities and associations, meanwhile, African Americans created their own amateur associations in the 1920s. In tennis, Black players founded the American Tennis Association (ATA) in 1916. Black golfers founded at least fourteen clubs in eight states and Washington, D.C. during the 1920s.

Segregated sporting institutions provided athletic opportunities for African American athletes during the era when they were excluded from white venues and served as a base of operations to develop the skills needed ultimately to re-integrate sports.

Black Athletes on the International Stage

The modern Olympics began in 1896 in Athens, Greece, and at the 1904 Games in St. Louis George Coleman Poage became the first African American to win a medal.

Louise Stokes holding a track meet trophy, c.1931 (left). Alice Coachman Davis, pictured here in 1948, was the first black woman to win an Olympic gold medal (middle). Tidye Pickett training for Olympic hurdles, 1936 (right).

The 1932 Games returned to the United States, this time hosted by Los Angeles. Amid the Great Depression, the 1932 Olympic Games set the standard for modern Olympics, introducing the medal stand, photo finishes, an Olympic Village, and the first Olympic torch, which burned atop the Los Angeles Coliseum.

Six African American men made the 1932 Olympic Team, highlighted by sprinters Ralph Metcalfe and Eddie Tolan and broad jumper Eddie Gordon. Tolan and Metcalfe finished first and second in the 100-meters, in what was then the closest finish in Olympic history. Gordon brought home the gold in his signature event as well.

The American press lauded Tolan and Metcalfe for restoring America's dominance in the sprinting events but had little to say about the segregation they faced off the track. Moreover, the white press often referred to these two college graduates as "boy." Olympic medals did not alter African Americans’ status as second-class citizens.

Moreover, Black women were prevented from equaling their male peers' feats. Sprinters Louise Stokes and Tidye Pickett both qualified for the Olympic team but were replaced by white athletes when the team reached Los Angeles. Pickett recalled that it was "prejudice, not slowness" that kept her and Stokes out of the 1932 Games.

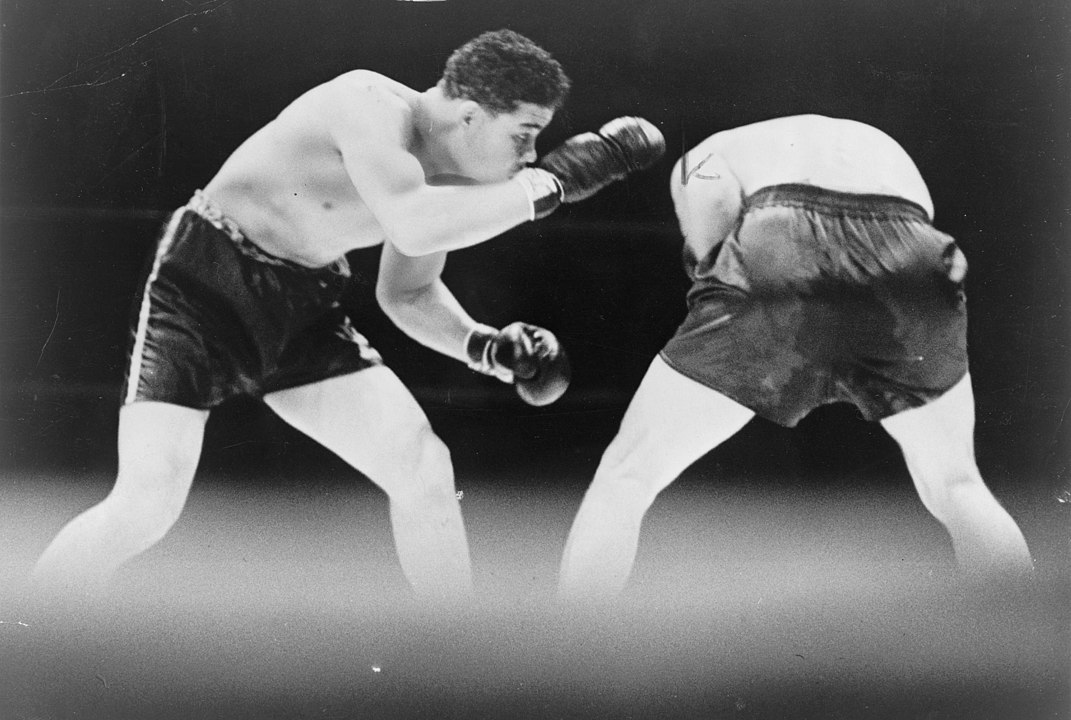

American Joe Louis fights German Max Schmeling in 1936.

The infamous Nazi Games of 1936, held in Berlin, might have become an international referendum on racism and should have thrown the light on American racism. Just weeks before the Games began, the German Max Schmeling pulled a shocking upset of Joe Louis, the "Brown Bomber."

Amid the swirling international politics, the Nazis saw the victory as a validation of their racist ideology. Joseph Goebbels, the Nazis' chief propagandist, wrote in his diary, "Schmeling fought for Germany and won. The white man over the black …. The whole family is in ecstasy.” Louis's defeat devastated Black America, many believing the loss would sustain the prejudice against Black fighters.

The Nazis fully intended to use the Games to reinforce their racial doctrines. Eighteen Black athletes—including the first Black women Olympians, Stokes and Pickett—represented the United States in Berlin.

Their performance gave the lie to Hitler's notion of Aryan supremacy.

Cornelius Johnson and Dave Albritton finished first and second in the high jump, and John Woodruff won gold in the 800-meters. Mack Robinson, Jackie Robinson’s older brother, finished second to Jesse Owens in the 200-meters. Ralph Metcalfe won two medals, a gold and a silver, in his second Olympics. Most famously, Jesse Owens captured four gold medals. Unfortunately, Pickett broke her foot in the hurdles and did not medal, while Stokes was an alternate and did not race.

Led by Owens, the Black American stars of the 1936 Olympics proved that Aryan superiority was a myth. But America was just as hostile to its returning stars. While Metcalfe found steady employment, Owens was reduced to racing against animals to earn a living. Mack Robinson became a street sweeper in Los Angeles, using his Olympic jacket to keep warm.

Still, the international dimensions of racism and sports remained through the WWII era. In 1938, soon after the Austrian Anschluss marked the beginning of Nazi expansionism, Joe Louis, having defeated James Braddock the year before to become the first Black heavyweight champion since Jack Johnson, larruped Max Schmeling in a rematch. Landing thirty-one of forty-one punches to Schmeling's two, Louis triumphed in a first-round technical knockout.

The fight was for more than the title. Anti-Nazi demonstrators had met Schmeling when he arrived in New York to train. In a ghostwritten article, Louis said: "Tonight I not only fight the battle of my life to revenge the lone blot on my record, but I fight for America against the challenge of a foreign invader, Max Schmeling. This isn't just one man against another or Joe Louis boxing Max Schmeling; it's the good old USA versus Germany."

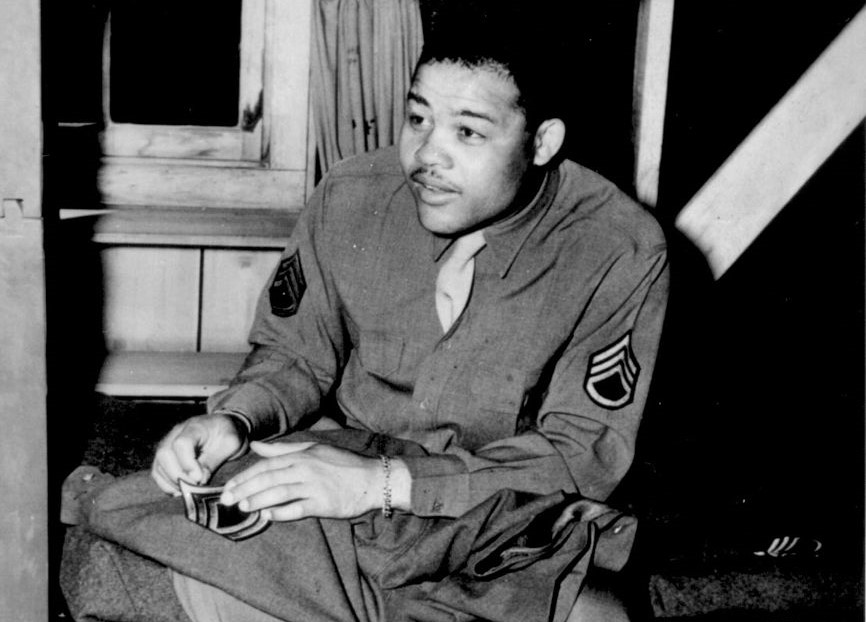

Joe Louis sews on the stripes of a technical sergeant to his army uniform, 1945.

The clean-living and humble Louis became the first Black athlete outside of the Olympic Games to represent America internationally. He cemented this position when he volunteered for World War II. Indeed, many Black athletes and coaches supported the "Double V Campaign:" victory abroad over the Axis Powers, and at home over segregations.

For instance, Florida A&M football coach William Bell, a former star player at Ohio State University, wrote a letter to Franklin Roosevelt arguing that America's war effort was an opportunity to improve race relations. "This is our America which we all love and for which we want to do our part in defending." Bell also volunteered for the American war effort.

Civil Rights and the Revolt of the Black Athlete

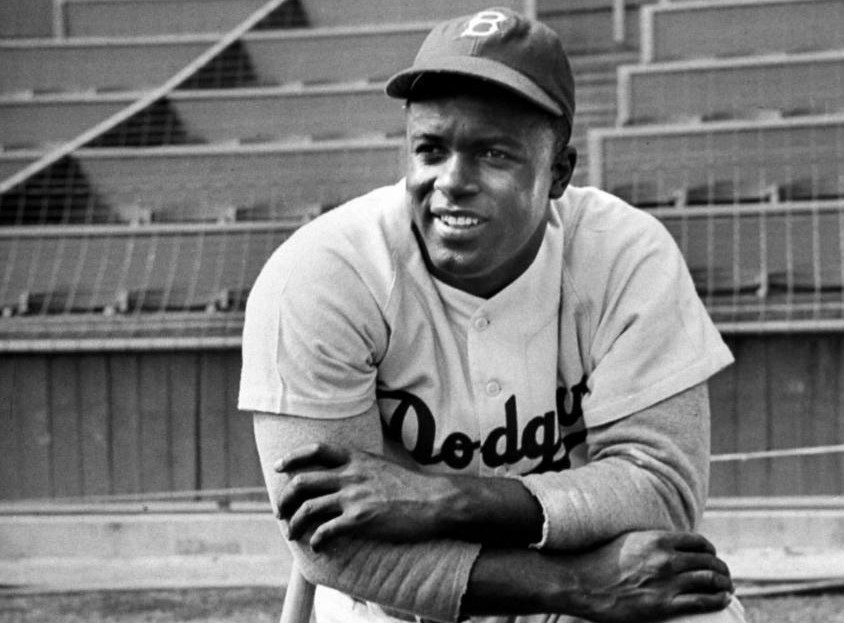

In 1962, Jackie Robinson was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. In honor of the occasion, Martin Luther King, Jr., noted his accomplishments in desegregating Major League Baseball, but also his activism.

"In the North, Jackie Robinson has fought constantly to expose hypocrisy in northern school systems,” wrote King. “He has counselled [sic] a greater use of the ballot as he has worked indefatigably for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People." King concluded, "He was a sit-inner before the sit-ins, a freedom rider before the freedom rides."

Jackie Robinson during filming of The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950.

Most are now familiar with Robinson breaking the color line in Major League Baseball in 1947. King's remarks signal that for Robinson and so many other Black athletes, playing the game was always about more than playing the game. Successful on and off the field, he became a model for Black athletes in the civil rights era.

Robinson's breakthrough began a series of civil rights gains in sports that paralleled the larger movement. In 1946, Kenny Washington and Woody Strode re-integrated the NFL. Alice Coachman became the first Black woman to medal when she took gold in the high jump at the 1948 Olympics. Althea Gibson broke the USLTA's color line in 1950, ultimately winning Wimbledon in 1957. The desegregation of American sports provided a valuable reference point for civil rights activists.

While Brown v. Board of Education(1954) provided the legal mechanism for southern colleges to desegregate their student bodies, integrated professional sports spurred southern college teams after 1961 to begin slowly desegregating their athletic programs.

Bill Russell during his first years with the Celtics franchise, c. 1960.

Athletes also followed Robinson's example off the field. For instance, Bill Russell, the star center for the NBA's Boston Celtics, declared in 1961 that he would no longer accept Jim Crow accommodations when the team travelled. Russell actively supported the civil rights movement, leading rallies in Boston and organizing basketball camps during the SNCC's 1964 Freedom Summer campaign in Mississippi. He explained his actions by simply stating that "this is a burden that must be shared by all."

In the mid-1960s, Jim Brown, at the height of his dominance on the professional football gridiron, declared racial discrimination was unacceptable to him and all black people. "I may very well make more money this year than any Negro athlete in the world, yet I want just as deeply the poorest sharecropper to be a free man." Additionally, Black players in the American Football League (AFL) boycotted the 1965 All-Star Game held in New Orleans because of discriminatory treatment.

The Black Power movement that emerged in the mid-1960s changed the tone, tenor, and strategies of black athletes' support for racial equality. No athlete embodied the Black Power moment more than Muhammad Ali.

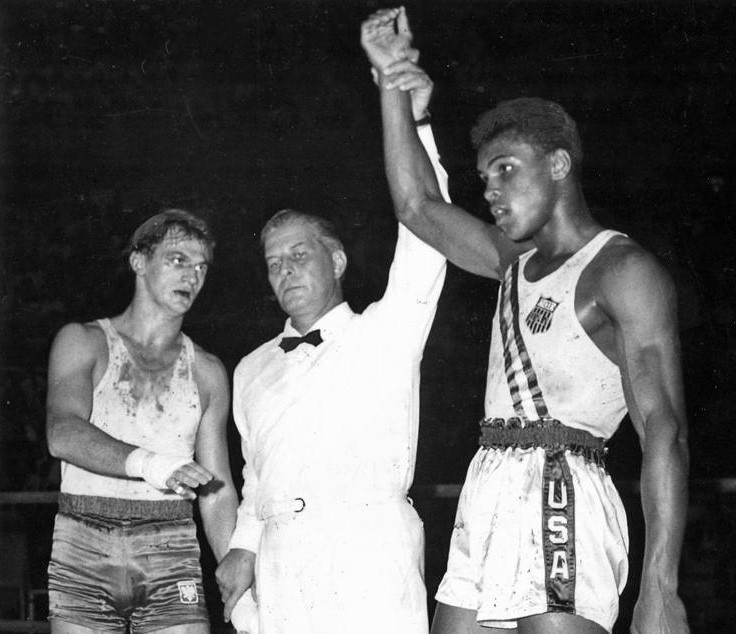

Cassius Clay, the Louisville, Kentucky native, won a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome. By 1961, Clay had joined the Nation of Islam (NOI), a black nationalist religious organization that preached racial separatism and for which Malcolm X was the most popular and influential spokesperson. When Ali refused induction to the United States Army during the Vietnam War in 1966, he quickly became the symbol of athlete as radical.

Zbigniew Pietrzykowski (left) and Muhammad Ali (right) at the Rome Olympics in 1960.

Just as Black Power activists like Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) were tired of the slow pace of change in the civil rights movement, Black athletes lamented the token integration their presence often symbolized.

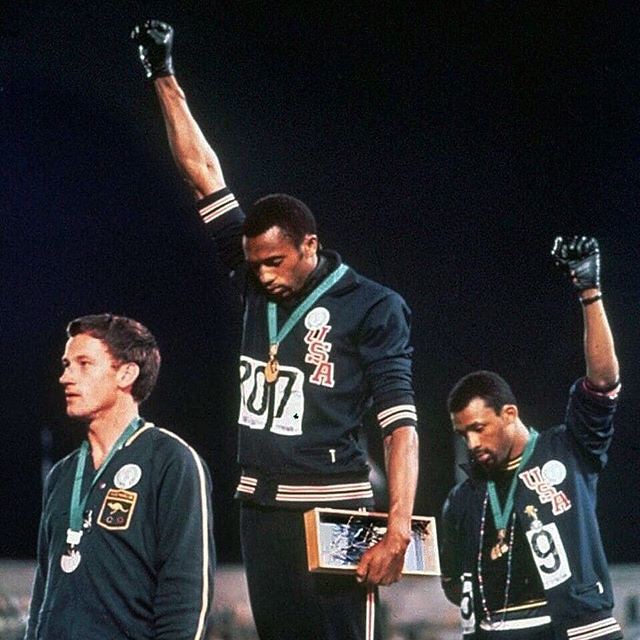

Harry Edwards, scholar and organizer of several athletic protests during the Black Power era, described the period beginning with Ali's protest as the revolt of the Black athlete. Edwards planned a boycott of the 1968 Olympics. Although the boycott did not happen, John Carlos and Tommie Smith conducted their now iconic raised black-gloved fist protest on the medal. Lee Evans wore a black beret while raising his fist after winning the 400-meters.

Protest carried considerable costs.

Ali was stripped of his title and could not box in what should have been the prime of his career. John Carlos and Tommie Smith were kicked out of the Olympics and struggled to find work when they returned home. Jackie Robinson died of a heart attack in 1972 at age fifty-three, in part from the stress of integration.

After college athletes engaged in many protests on college campuses, in 1973, the NCAA provided coaches and schools more power over players by reducing athletic scholarships to one-year renewable agreements. Protest by Black athletes on and off the field was costly personally and professionally.

“Be Like Mike”

In 1975, Hertz Rental Car Company paid football star O. J. Simpson $100,000 to become the company's spokesperson. Simpson was representative of the Black athlete who chose to be non-confrontational about race and was richly rewarded with endorsement deals. Within a decade, endorsements were a significant source of income for star players.

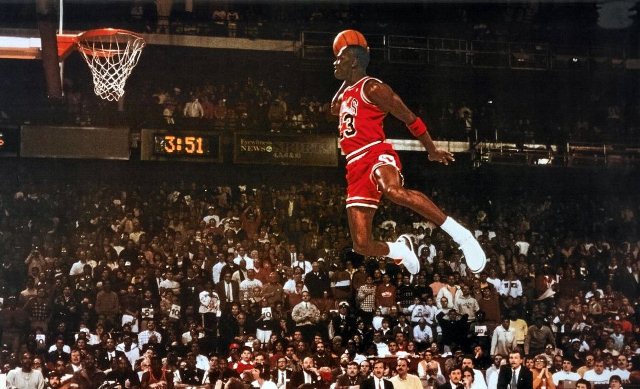

Michael Jordan during his time with the Chicago Bulls, c. 1990.

No Black athlete embodied that apolitical attitude more than Michael Jordan. For example, in 1990, Michael Jordan refused to endorse Harvey Gantt's bid for North Carolina senator against notorious racist Jesse Helms. Jordan quipped that "Republicans buy sneakers, too." Gatorade encouraged kids to "Be Like Mike,” which alluded to Jordan's greatness but referred to his lack of activism as well.

Black athletes still protested even if superstars refrained. Jordan’s teammate Craig Hodges handed President George H. W. Bush a letter expressing concern about racism and imperialism during the Chicago Bulls' visit to the White House. The Denver Nuggets' Mahmoud Abdul-Rauf refused to stand for the National Anthem in 1996 to protest America's racism. Yet the activism by Hodges and Abdul-Rauf paled in comparison to the silence of Michael Jordan.

Racism certainly hadn’t disappeared from the athletic world. Venus and Serena Williams burst on the tennis scene in the late 1990s and came to dominate it in the 2000s. Because they came from South Central Los Angeles to the top of the tennis world, the sisters ruffled feathers. Venus and Serena Williams endured racist innuendo, comments about their body, and critiques about their ultra-competitive demeanor on the court.

Serena and Venus Williams at the 2013 US Open.

At the 2001 Masters Tournament in Indian Wells, eighteen-year-old Serena entered the final match to a cascade of boos, including fans shouting the N-word. Serena won the title, but both she and Venus boycotted Indian Wells for fourteen years.

Although it was because of personal attacks, the women's boycott of Indian Wells represented a return of elite Black athletes resisting racism. In the relative silence from leading Black male athletes, the Williams sisters represented a stark change from Black athletes prioritizing money over racial politics.

The Trayvon Generation

On the night of the 2012 NBA All-Star Game in Orlando, Florida, twenty-five miles away in Sanford, Florida, George Zimmerman killed seventeen-year-old Trayvon Martin as the teenager was returning home from a nearby store. Zimmerman was a so-called community watchman who racially profiled Martin because he was wearing a hoodie and shot Martin after an altercation.

Star Black athletes, such as LeBron James and Dwayne Wade, wore hoodies to demonstrate their outrage. But absent a broader political movement, the Trayvon protests were poignant yet unfocused.

In the aftermath of George Zimmerman's acquittal in 2013, activists on social media starting using #BlackLivesMatter. The murder of Michael Brown in August 2014 outside of St. Louis led activists to transform the slogan into the Black Lives Matter Movement. Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi had started the hashtag and, after Brown's murder, set out to transform it into a decentralized activist organization aimed at criminal justice reform.

The Black Lives Matter slogan and movement provided Black athletes a broad framework to express their activism.

When players in the WNBA wore Black Lives Matter shirts in 2016 after the murder of Philando Castile in St. Paul, Minnesota, the League fined the teams and the players. Off-duty police walked out of the Minnesota Lynx game after the team came out in Black Lives Matter shirts. In response to the fines, Tina Charles, a former WNBA MVP, stated, "I refused to be silent."

NFL quarterback Colin Kaepernick also grew frustrated at the wave of police violence in 2016, including the police shootings of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, and Charles Kinsey, as well as the acquittal of the police involved in the death of Freddie Gray.

Kaepernick began kneeling during the national anthem as a form of protest. Soon, leading athletes in several leagues joined Kaepernick in kneeling during the anthem to protest police brutality.

When the WNBA and the NBA returned to play in the summer of 2020, the phrase "Black Lives Matter" was stenciled on the floor. Players chose slogans such as "Say Her Name," "I Can't Breathe," "Equality," and others for the back of their jerseys.

The players in the WNBA went further. US Senator and WNBA over Kelly Loeffler had spent months before the Covid “bubble” berating players' support of Black Lives Matter. The players urged Georgia voters to support Loeffler's opponent in the 2020 US Senate race, Rev. Raphael Warnock, wearing t-shirts printed with "Vote Warnock." The support of the WNBA players helped launch Warnock to a historic victory as the first African American Senator from Georgia.

Additional protests occurred inside the NBA bubble. When the police shot Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in August 2020, the Milwaukee Bucks decided not to play their playoff game. This wildcat strike was the culmination of activism by athletes in the Trayvon Martin Generation.

Those protests by Black athletes in 2020 reflect more than a century of Black athletic activism. The tactics and slogans have changed, but the overall goal has been equality and justice for Black communities. Black athletes have understood that their talents provide a powerful voice for Black communities. They have never heeded the command to "Shut up and dribble."

Bryant, Howard. The Heritage: Black Athletes, A Divided America, and the Politics of Patriotism. Boston: Beacon Press, 2018.

Eig, Johnathan. Ali: A Life. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017.

Lanctot, Neil. Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004.

Lansbury, Jennifer. A Spectacular Leap: Black Women Athletes in Twentieth-Century America. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 2014.

Moore, Louis. We Will Win the Day: The Civil Rights Movement, the Black Athlete, and the Quest for Equality. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2021.

Ward, Geoffrey C. Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson. New York: Vintage Books, 2004.

White, Derrick E. Blood, Sweat, and Tears: Jake Gaither, Florida A&M, and the History of Black College Football. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2019.

Wiggins, David K., and Drew A. Swanson, eds. Separate Games: African American Sport Behind the Walls of Segregation. Little Rock: University of Arkansas Press, 2016.