June 12th marks the anniversary of the Supreme Court's Loving v. Virginia case that struck down laws prohibiting interracial marriage. More than fifty years later, it seems absurd to most of us that such laws ever existed in the first place. But, as historian Jessica Viñas-Nelson explains, the fear of interracial marriage has been at the center of America's racial anxiety for a very long time.

In June, many Americans marked Loving Day—an annual gathering to fight racial prejudice through a celebration of multiracial community. The event takes its name from the 1967 Supreme Court ruling in Loving v. Virginia. The case established marriage as a fundamental right for interracial couples, but 72 percent of the public opposed the court’s decision at the time. Many decried it as judicial overreach and resisted its implementation for decades.

The case that brought down interracial marriage bans in 16 states centered on the aptly named Richard and Mildred Loving. In 1958, the pair were arrested in the middle of the night in their Virginia home after marrying the month before in Washington, D.C. Pleading guilty to “cohabiting as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth,” they were offered one year imprisonment or a suspended sentence if they left their native state.

A 2013 Loving Day celebration in New York City (photo by Willie Davis).

The Lovings chose exile over prison and moved to D.C. but they missed their hometown. After being arrested again in 1963 while visiting relatives in Virginia, Mildred Loving wrote Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who in turn referred her to the American Civil Liberties Union. The ACLU appealed the Lovings’ conviction, arguing interracial marriage bans contradicted the Fourteenth Amendment’s equal protection clause. Despite this line of argument, lower courts upheld the verdict because, as one jurist wrote, “the fact that [Almighty God] separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

After multiple appeals, the case reached the Supreme Court, where Chief Justice Earl Warren’s opinion for the unanimous court declared marriage to be “one of the ‘basic civil rights of man’…To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications…is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty.” Warren further ruled that interracial marriage bans were designed expressly “to maintain White Supremacy.” The court’s decision not only struck down an 80-year precedent set in the case Pace v. Alabama (1883), but 300 years of legal code.

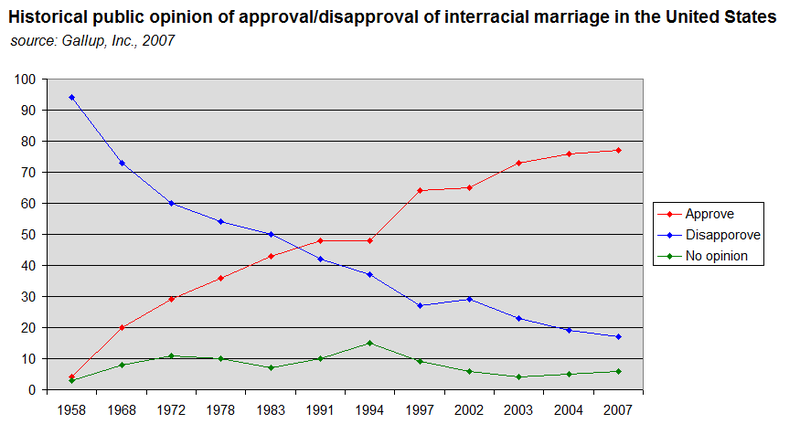

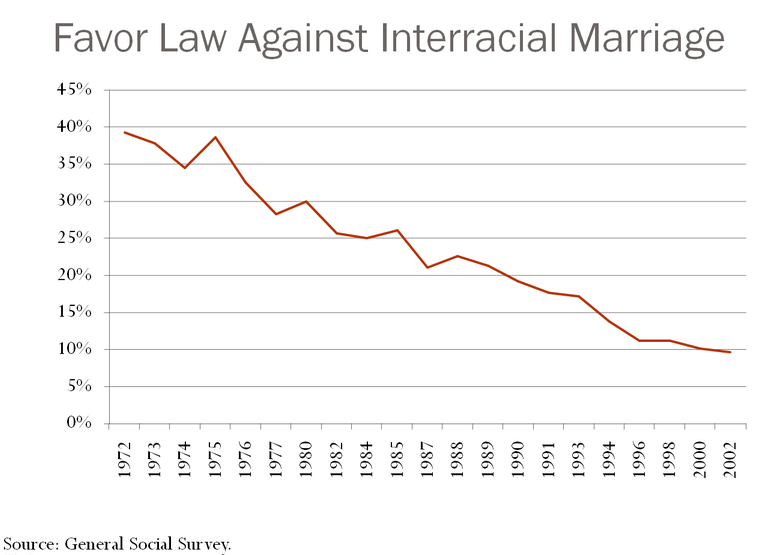

A chart depicting American approval and disapproval of interracial marriage from 1958 to 2007.

In the decades that followed, the nation’s views on interracial marriage have undergone a slow sea change. In 1967, only 3 percent of newlyweds were interracial couples. Today, 17 percent of newlyweds and 10 percent of all married couples differ from one another in race or ethnicity. Even though legal in most states by 1959, the overwhelming majority of white Americans then believed rejecting interracial marriage to be fundamental to the nation’s well-being. In 2017, in contrast, 91 percent of Americans believe interracial marriage to be a good or at least benign thing.

Today, few would publicly admit to opposing interracial marriage. In fact, most Americans now claim to celebrate the precepts behind Loving and the case has become an icon of equality and of prejudice transcended. Accordingly, individuals across the political spectrum, from gay rights activists to opponents of Affirmative Action who call for colorblindness, cite it to support their political agendas.

Yet, for 300 years, interracial marriage bans defined racial boundaries and served as justification for America’s apartheid system. And 50 years on, many of their effects remain.

Founding Myth, Foundational Rejection

The first recorded interracial marriage in American history was the celebrated marriage of the daughter of a Powhatan chief and an English tobacco planter in 1614. Matoaka, better known as Pocahontas, did not wed Captain John Smith as the Disney version of her life implies. Instead, she married John Rolfe as a condition of release after being held captive by English settlers for more than a year.

Rolfe presented her, duly baptized, in England as a symbol of peace, an example of England’s “civilizing” potential in the New World, and a means to raise funds for the Virginia Company’s colony. She died in England soon thereafter and the peace brokered with the marriage collapsed.

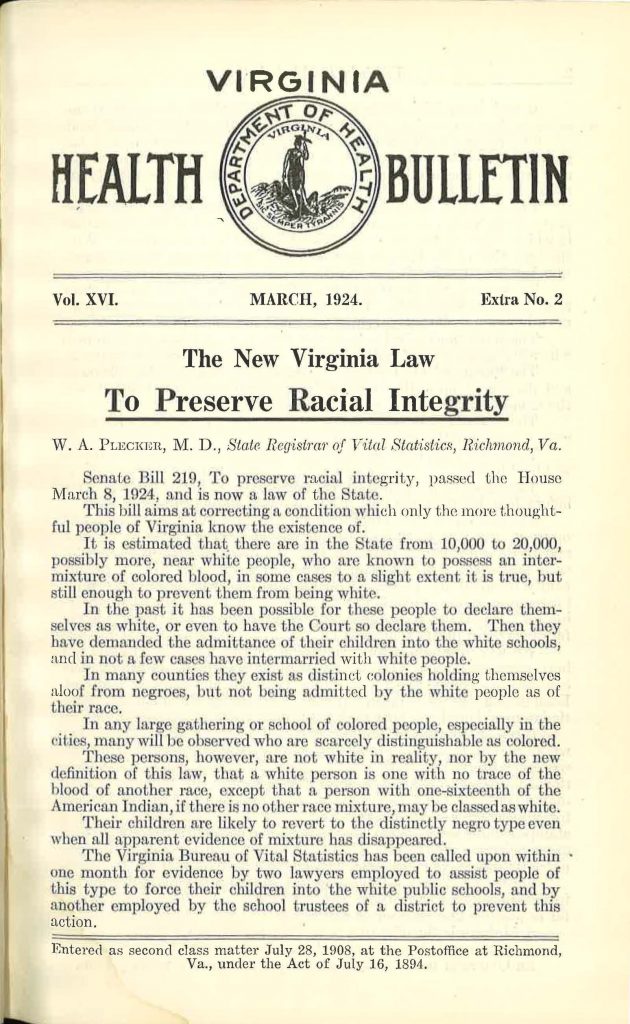

This first marriage obtained mythic portions long before Disney remade the story and even shaped Virginia’s laws on interracial marriage. Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924 codified individuals as white only if they had “no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian,” except for those who had one-sixteenth or less blood from American Indians—the so-called “Pocahontas exception”—a concession to some elite families who claimed lineage from Rolfe and Pocahontas’s only child.

|

While Rolfe—and his alleged future descendants—won esteem for association with an “Indian princess,” relatively little racial mixing occurred between English settlers and Native Americans. English prejudice against a “savage” people, religious injunctions against marrying non-Christians, and a smaller imbalance in gender ratios among English colonists than in French and Spanish colonies contributed to this outcome—not to mention Indian women’s disinclination to select Englishmen, who were much less adept than Native men at hunting, fishing, and other valued skills.

The first laws proscribing interracial relationships, however, did not pertain to Native-English unions but to ones colonial leaders feared would upend the social order because they could promote alliances between indentured servants and slaves.

In 1664, Maryland sought to stanch potential interracial marriages by threatening enslavement for white women who married black men. Two years earlier, Virginia had enacted legislation to profit from white men’s sexual relationships with black women. Children would inherit the social status of their mother, not their father, meaning the children of slave women would be born slaves regardless of the father’s status. Virginia then outlawed interracial marriage entirely in 1691. Virginia’s original penalty for those who wed interracially—banishment—was the same punishment the Lovings received nearly three centuries later.

These laws had clear aims: to control women’s sexuality, to establish categories of slave and free, and to develop racist ideologies justifying discrimination. White men had sexual access to all women and exclusive access to white women. Interracial sex, so long as it remained out-of-wedlock and occurred between white men and black women, merited little legal or social consequence. These laws also set into motion America’s peculiar system of racial classification: hypodescent. Americans would be classified not according to the degree of mixture they contained but by the total absence or presence of blackness.

The first laws prohibiting interracial marriages occurred when wealthy planters were transitioning from using European indentured servants as their primary labor to African slaves. As these two labor pools worked alongside one another and even married one another, planters feared that poor whites and African slaves would overthrow the far smaller planter class.

Interracial marriage bans, therefore, arose to build racial barriers that would supplant alliances among the laborers by creating binary categories of black and white, slave and free. Indeed, Maryland’s assembly passed the statute discouraging marriage between white women and black men within an act authorizing lifelong slavery.

Most other American colonies followed Maryland and Virginia’s lead and banned interracial marriage between 1661 and 1725. Forty-one states in all eventually enacted bans.

“The Battering Ram”: Interracial Marriage and the Age of Abolition

Northern colonies and later states also enacted bans on interracial marriage, although some repealed these as they gradually abolished slavery. Nevertheless, white fears of mixed marriages remained a potent political force, particularly in the North.

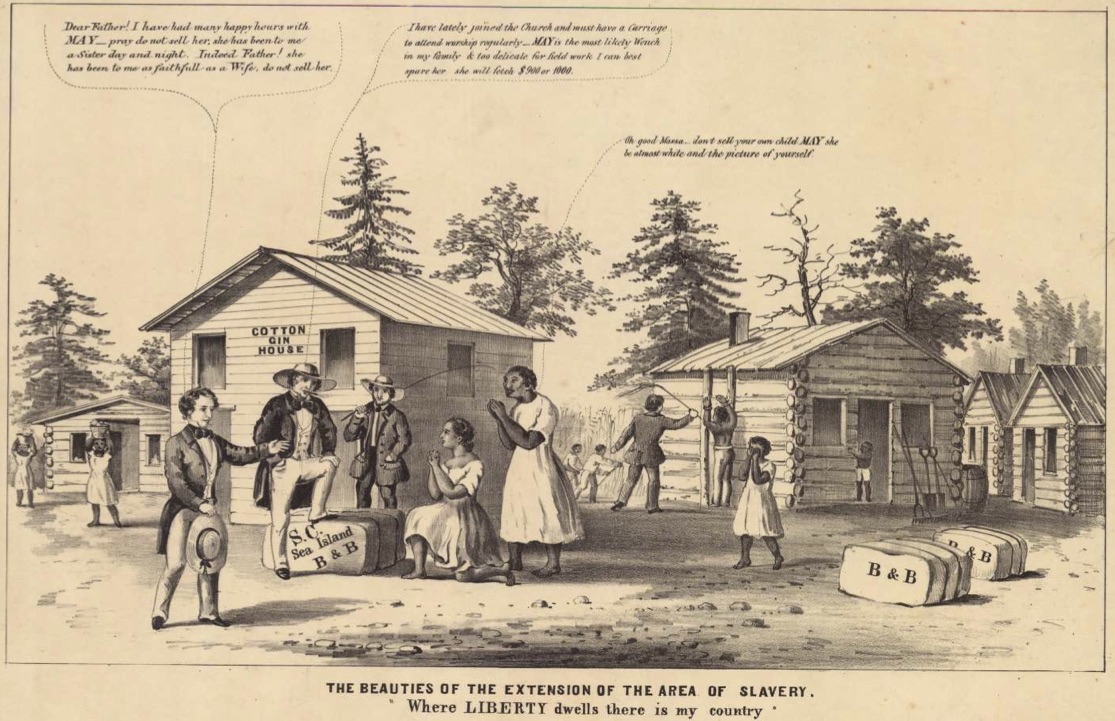

Most white northerners showed themselves firmly opposed to any suggestion of black equality through their rejection of interracial marriage or even the mere hint of its occurrence. Not coincidently, public hysteria against interracial marriage grew louder in the 1830s when the rights of black people were being contentiously debated and a more vocal and inclusive abolitionist movement emerged. Defenders of slavery accused abolitionists of coveting interracial marriages, despite the undeniable evidence of interracial offspring on Southern plantations resulting from slave owners forcing themselves on slave women.

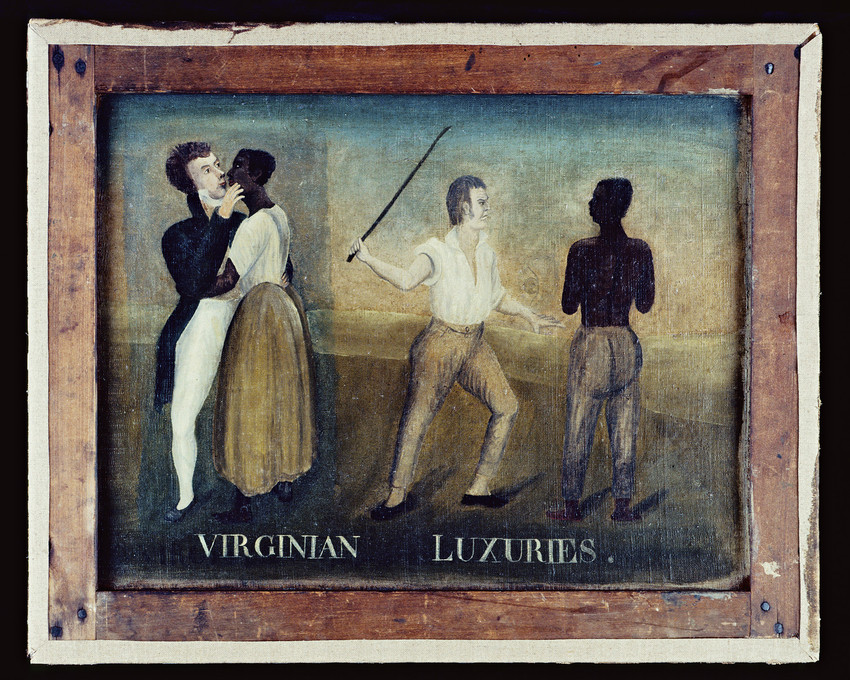

A double-sided painting from New England c1825, Virginia Luxuries features a bust-length portrait on one side and the above image on the reverse. The double-side nature of the painting serves two purposes: as a commentary that behind the respectable exterior of white Virginia gentlemen lies perverse desires and as a means for the owner of the painting to hide its controversial side from unreceptive viewers.

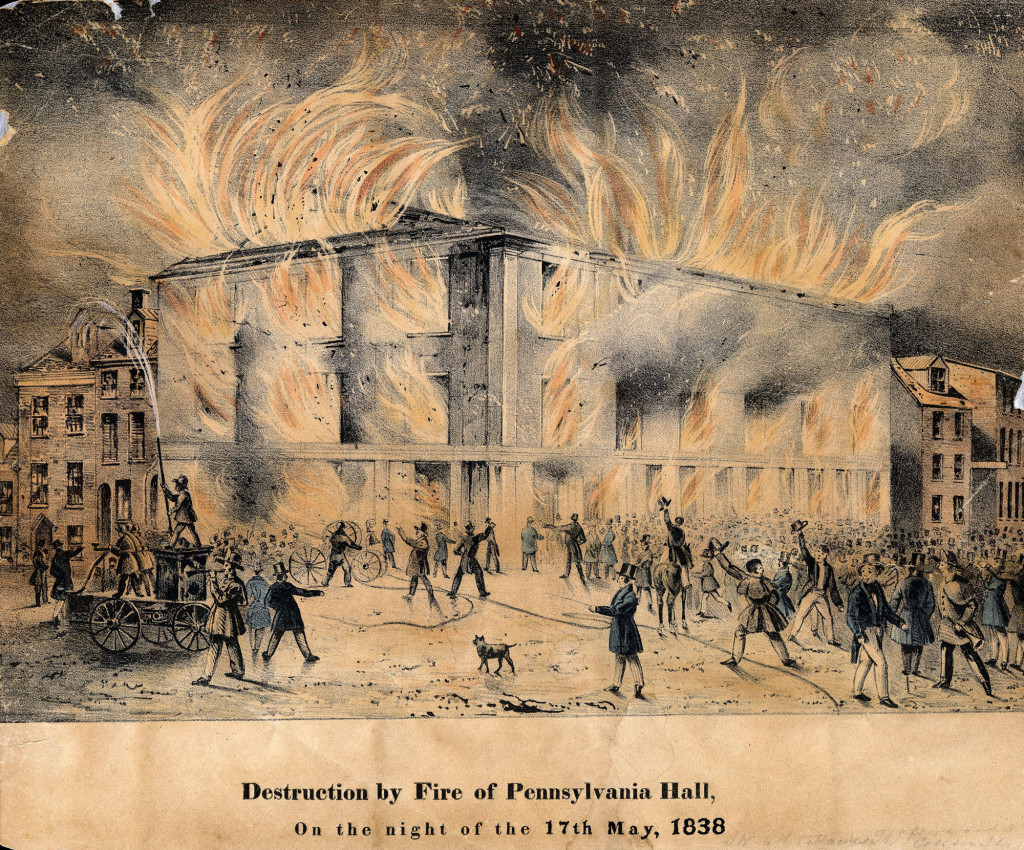

After rumors spread in 1834 that abolitionist ministers had married an interracial couple (they hadn’t), 11 days of racial terror erupted in New York City. A mob attacked a mixed-race gathering of the American Anti-Slavery Society and continued to menace, burn, and destroy the homes and churches of leading abolitionists. The mob’s wrath targeted black churches, homes, schools, and businesses. A similar riot, with similar instigation and targets of violence, occurred in Philadelphia in 1838.

As the targeted violence against abolitionists and black institutions illustrates, by the 1830s, interracial marriage had become a proxy for white anxieties that the social order they had built upon racial distinction might be endangered. Abolition threatened the social order and thus supporters of slavery raised fears of interracial marriage to torpedo abolitionists’ efforts and to hurt the free black population.

Many of the 165 anti-abolitionist riots that took place in the 1830s were provoked by rumors of interracial marriages. Little else could more effectively raise a mob or garner as much wrath; anti-abolitionists used this to great effect. In 1838, the black-authored newspaper Colored American astutely labeled the tactic “the battering ram of the pro-slavery party.”

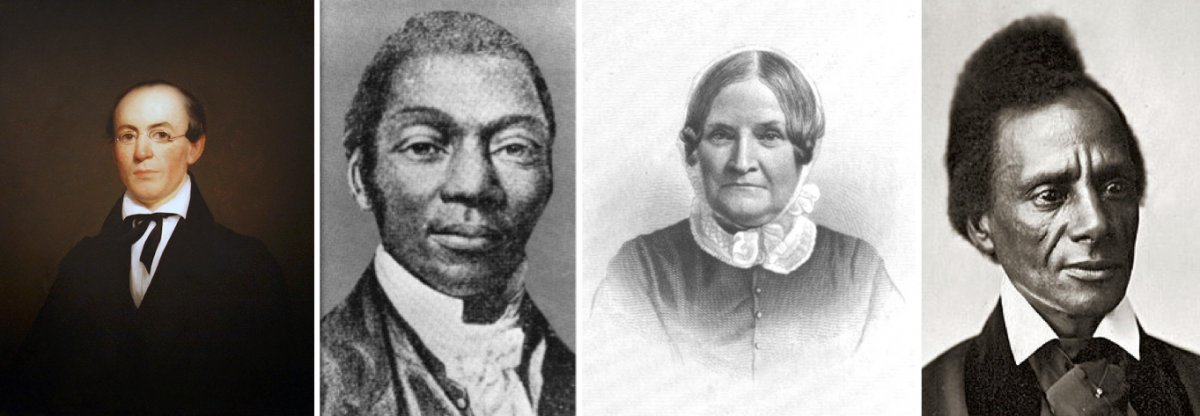

Despite allegations that abolitionists were amalgamationists (supporters of interracial marriage), most in fact opposed interracial marriage and readily crumbled before the oft-repeated question: “Would you let your daughter marry a Negro?”

Even William Lloyd Garrison, one of the most radical abolitionists, never advocated actual interracial marriages even as he fought for the repeal of marriage bans. Garrison explained that abolitionists’ support for repealing interracial marriage bans “has not been to promote ‘amalgamation,’ but to establish justice.”

Such marriages among abolitionists were also exceedingly rare. One of the few known interracial marriages between abolitionists—William King and Marry Allen (1853)—resulted in their fleeing the country in fear for their lives.

Abolitionist and publisher William Lloyd Garrison spoke out about the injustice of interracial marriage bans (left). Abolitionist and writer David Walker called for black unity against racial injustice in 1829 (second from left). Abolitionist, writer, and women’s rights advocate Lydia Maria Child argued for the right to interracial marriage in principle, not in practice as she maintained “no abolitionist considers such a thing desirable” (third from left). Orator and abolitionist Charles Lenox Remond considered the legality of interracial marriage the epitome of rights necessary for a free and open society and fought for the repeal of Massachusetts’s ban in 1843 (right).

Most African Americans too were ambivalent toward marrying interracially. They saw the importance of obtaining the legal right to it in principle, but took pains to deny allegations that they coveted such unions and vehemently decried slave owners’ rape of enslaved women. Perhaps the era’s most famous black pronouncement on the matter came from David Walker’s revolutionary Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World (1829) when he declared: “I would not give a pinch of snuff to be married to any white person I ever saw.” Nevertheless, he argued that marriage bans were a hallmark of inequality and he sought their removal on principle.

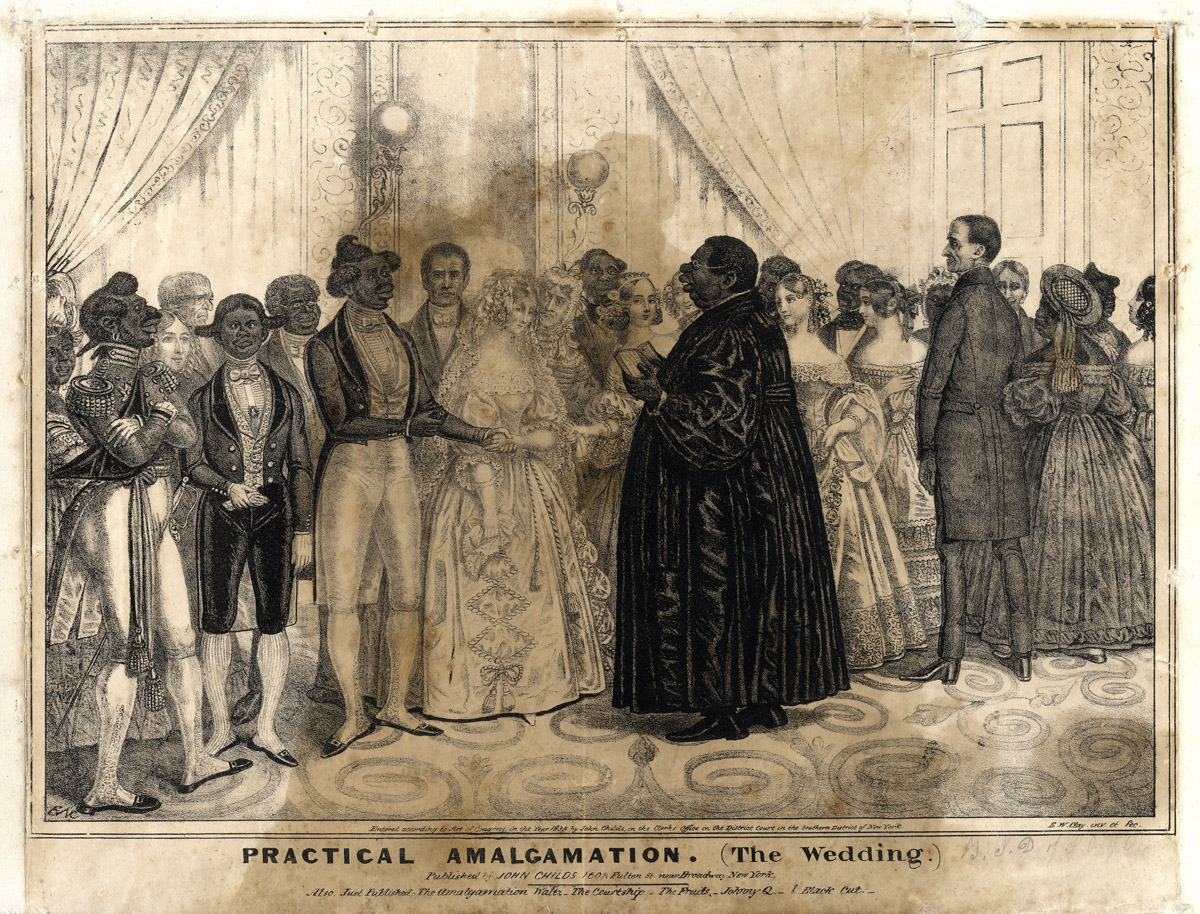

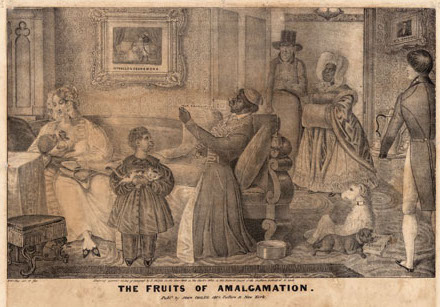

Even where interracial relationships were legal, derogatory depictions—like E.W. Clay’s popular series of lithographs—linked it in the white public’s imagination with bastardy, debauchery, and immorality. In rare cases though, interracial couples inside and outside of legal wedlock existed and sometimes even thrived in pockets of the North where local communities paid far less concern than one might expect. Even if community tolerance existed, however, the children of interracial couples unable to legally wed were defined as bastards—a branding that carried real consequences in the 18th and 19th centuries as it foreclosed the possibility of inheritance—meaning white property remained in white hands.

For the enslaved population, however, no such consensual interracial relationship could exist. Even the rare and seemingly loving unions that functioned like marriages between masters and slaves could not—by definition—be consensual. Most interracial sex under slavery, however, did not even have a veneer of loving attachments and was instead the blatant rape of black women by white men. This history’s effect on African Americans’ views of interracial relationships cannot be overstated.

Nor can interracial marriage’s role in politics and legal history be exaggerated.

As part of the justification for the infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857) case, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney used the existence of interracial marriage bans as evidence that the Founding Fathers never intended Black Americans to be citizens. These laws, Taney insisted, were evidence of a “perpetual and impassable barrier erected between the white race and [those]…which they looked upon as so far below them in the scale of created beings that intermarriages between white persons and negroes and mulattoes were regarded as unnatural and immoral, and punished as crimes.”

The issue even arose in the legendary debates between Abraham Lincoln and Stephen A. Douglas. Douglas accused Lincoln of condoning amalgamation, to which Lincoln vehemently protested “that counterfeit logic which concludes that, because I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife.” Accusations, however, continued to plague Lincoln and took on a life of their own in the 1864 election.

Miscegenation and “Purity”

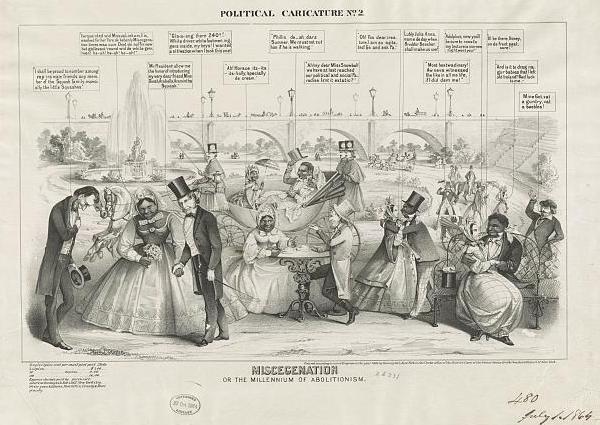

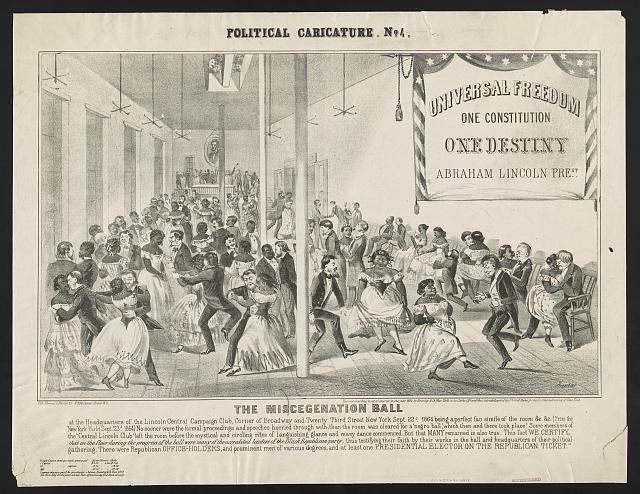

Resurrecting the false connections between abolitionism and amalgamation, Lincoln’s opponents invented a new term in the midst of the Civil War to describe interracial relationships: “miscegenation” (the blending of races). Aiming to cost Lincoln and his party the 1864 election, two Democrats (posing as Republicans) promoted the notion that the Republican Party not only condoned interracial marriages, but actively encouraged them.

An 1864 anti-Republican satire using white northerners’ fears of racial mixing.

The new term did not cost Lincoln reelection, but its overnight and enduring popularity highlights the public’s desire to describe something that had long been around, but suddenly seemed in need of a new moniker in order to associate it with heightened fear of black freedom. Miscegenation permanently rooted itself into America’s racial lexicon and the fear of it became a political wedge issue for at least a century thereafter.

Fears of miscegenation, interracial marriage, or “social equality” arose in nearly every debate over political, economic, and social rights. The topic would even make an appearance in the rationale for the Supreme Court decision that allowed the system of Jim Crow discrimination and supposed “separate but equal” to continue: the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) ruling. “Laws forbidding the intermarriage of the two races,” the court reasoned, “may be said in a technical sense to interfere with the freedom of contract, and yet have been universally recognized as within the police power of the State.” The foundation of post-Civil War white supremacy rested firmly upon opposition to miscegenation.

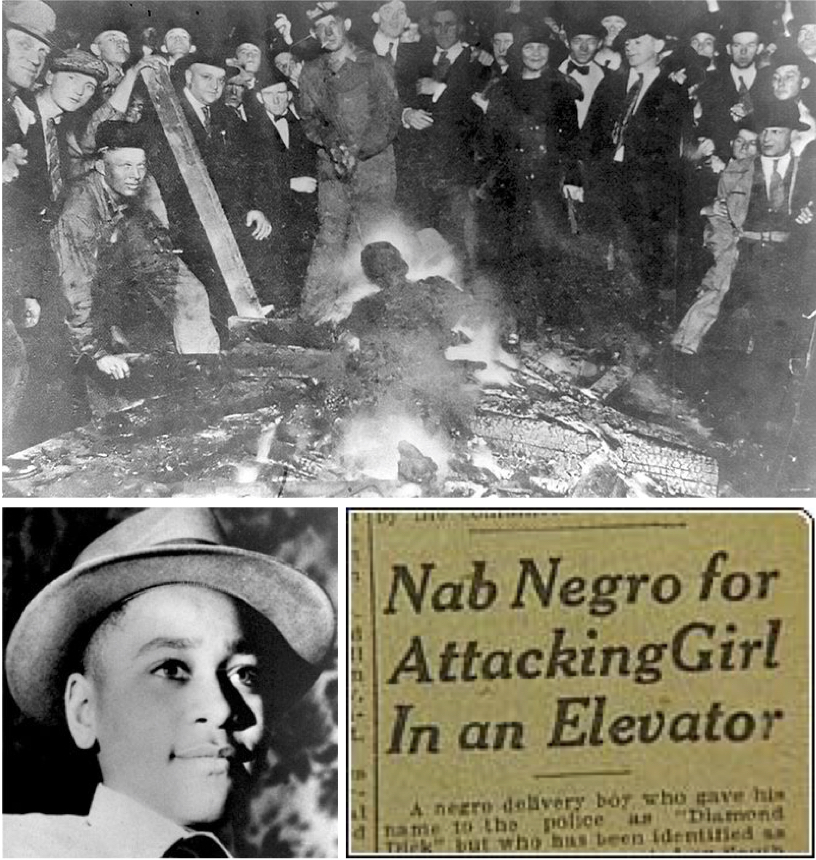

The far more chilling effect of irrational white fears over miscegenation, however, emerged outside of the court system: lynching.

Between 1882 and 1968, at least 3,446 black men were publicly and ritualistically murdered by white mobs. Roughly a third were accused of raping white women, but the alleged need to protect white women from black men—universally portrayed as violent, lustful, and savage—justified lynch mobs’ actions to the larger white public. Black journalist Ida B. Wells demonstrated that many of these accusations of rape stemmed from consensual interracial relationships that had been discovered by white women’s disapproving relatives. Nevertheless, the lynching continued, as did white fears about racial “purity.”

A close examination of almost any act of racial violence against African Americans reveals the specter of rape accusations. A mob hung, shot, and burned William Brown in Omaha, Nebraska in 1919 after he was accused of raping a white woman (top). Fourteen-year-old Emmett Till was brutally murdered in 1955 after supposedly whistling at a white woman (left). A 1921 newspaper article encouraging violence after a black teen allegedly assaulted a white teen in Tulsa, Oklahoma (right). The resulting riot leveled 35 blocks of the city’s black section and killed an estimated 39 to 300 African Americans.

The concept of racial “purity” evolved through interracial marriage law. In post-Civil War Arkansas, a black delegate to the state’s constitutional convention—William H. Grey—mocked a white delegate's insistence that interracial marriage be banned by questioning how such a feat could even be accomplished given that "the purity of the blood, of which the gentleman speaks, has already been somewhat interfered with."

Legislation would become a “farce,” Grey insisted, as scientific boards proved unable to draw a line between black and white given the extent of racial intermixture under slavery (perpetrated by white men, he pointedly noted). Although sound in principle, Grey proved incorrect in the end; state governments found ways to define race.

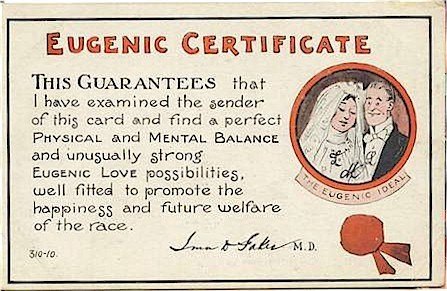

He was right, however, that the distinction between black and white would not be simple. States’ definitions of the degree of “blood quantum” required to be defined as being a particular race varied over time and place. By the 20th century, any known presence of African ancestry (the “one-drop rule”) became the measure in many states and in the white public’s imagination. Instead of prejudice lessening over time, whites grew increasingly paranoid about marrying someone with “invisible blackness” and took up genealogy en masse to ferret out “passers.”

A certificate from 1924 mockingly “guaranteeing” a person’s racial “purity."

Ultimately, county clerks served as the front line in determining race when couples requested marriage licenses and birth certificates. More than merely dictating who could marry each other, racial designations determined where a person could live, work, learn, and socialize.

As the cornerstone of the edifice of Jim Crow, the number of prohibitions against interracial marriage only increased in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as new states entered the Union.

Western states adopted prohibitions and included additional groups to discriminate against: people of Asian and American Indian descent. Revealing their true intent to be maintaining white “purity,” none of these laws bothered to prohibit interracial marriages among nonwhite groups or to prohibit marriage among different European nationalities. An Asian American and an African American were free to marry each other, but neither could marry a white person. In contrast, no laws prevented, say, an Italian American and a Polish American from marrying.

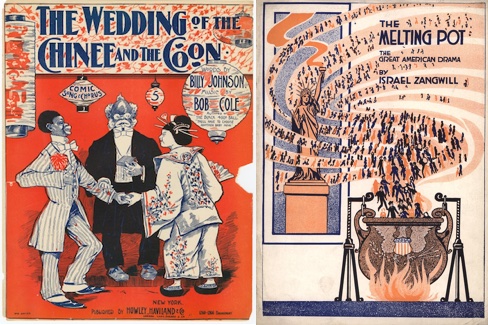

Sheet music from 1897 mocking African Americans and Chinese Americans (left). “The Melting Pot” analogy to celebrate America as a blend of nationalities first came into use with Israel Zangwill’s popular 1908 play of the same name (right). Conspicuously—and purposefully—absent from his melting pot were African Americans and Asian Americans who Zangwill believed should establish their own homelands elsewhere, even as he advocated for intermarriage among European nationalities.

Even where interracial marriage bans had been repealed, a prominent interracial marriage could ignite white hysteria. Every state in the North except Indiana had repealed its ban by 1887, but when World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Jack Johnson wed interracially in Chicago for the second time in late 1912, white America panicked. In 1913, the U.S. House of Representatives overwhelmingly passed a measure to prohibit interracial marriage in the District of Columbia. Eleven of the 19 states without prohibitions at that time introduced—and nearly passed—bans.

The panic diminished somewhat after an all-white jury convicted Johnson on trumped-up charges of crossing state lines with a woman “for immoral purposes,” but the precariousness of the issue remained a warning for would-be interracial couples and supporters of equal rights.

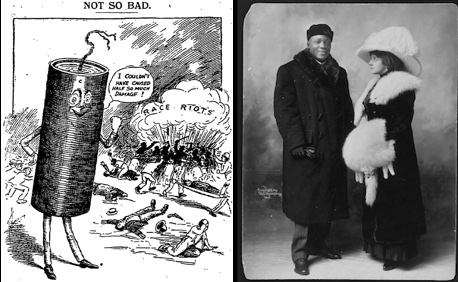

World Heavyweight Boxing Champion Jack Johnson and Etta Terry Duryea, the first of his three white wives, in 1910 (right). Attempts to ban interracial marriage at the federal level swept the nation after Johnson’s second marriage to a white woman in 1912. A 1910 cartoon referencing the race riots in more than 50 cities after Jack Johnson defeated the white boxer James Jeffries in what was billed “the fight of the century” and Jeffries the “Great White Hope” (left). Johnson's marriage to a white woman likely fueled rioters’ anger.

“One Bombshell at a Time is Enough”: Miscegenation and Civil Rights

Given the widespread public opposition—94 percent of white Americans opposed interracial marriage in 1958—most civil rights groups did not place repealing marriage bans at the top of their agendas.

Nevertheless, the modern campaign to overturn interracial marriage prohibitions began in California when a Hispanic woman legally defined as white and a black man sought to wed in 1947. In the resulting case, Perez v. Sharp (1948), the California Supreme Court became the first court in the 20th century to declare interracial marriage bans unconstitutional, violating California’s constitution. Fearing a similar decision from the U.S. Supreme Court, the state declined to appeal the decision, although the California legislature waited until 1959 to repeal its anti-miscegenation laws.

In the years that followed, facing weaker opposition to the marriage injunctions because of demographic differences, western states gradually repealed or overturned marriage bans. Despite appeals to the Supreme Court from various states, the highest court in the land steadfastly avoided hearing cases on the topic.

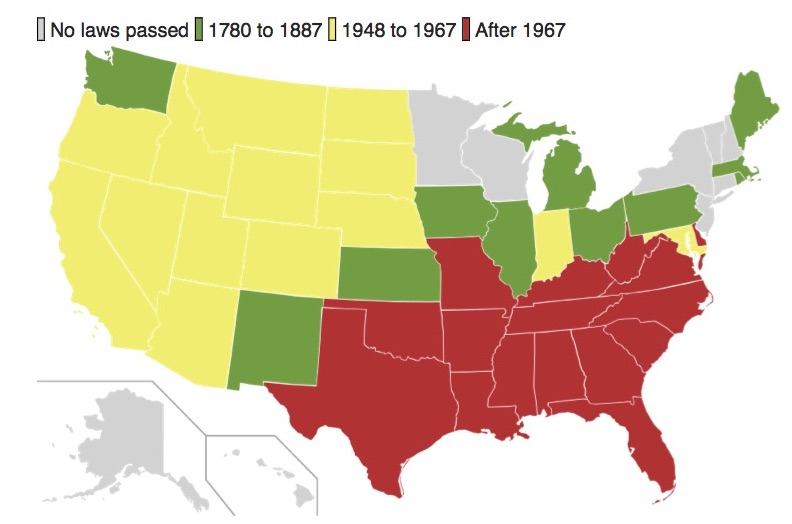

A map depicting the range of years in which states repealed interracial marriage bans.

Even cases on seemingly unrelated matters brought outrage from critics who lambasted the court for rulings that they insisted would lead to “race mixing.”

When a case challenging interracial marriage bans reached the Supreme Court just a year after Brown v. the Board of Education (1954), Justice Felix Frankfurter worried that ruling on the case would “seriously handica[p] the enforcement of … the [school] segregation cases” and he convinced his fellow justices to avoid the case. Justice Thomas C. Clark likewise concluded against hearing cases on interracial marriage bans after Brown, as “one bombshell at a time is enough.” Leading civil rights groups likewise stayed away from cases on interracial marriage for fear of damaging all other efforts.

Since the surprise victory in Perez, however, the ACLU had begun searching for an ideal test case to overturn bans everywhere. Given public sentiment, the ACLU sought to diminish resistance by finding a white male—preferably a veteran—seeking to marry a nonwhite—ideally Asian—woman.

|

Infringing upon a white male’s rights and avoiding the more controversial black-white pairing seemed the most promising strategy. Few such couples, however, desired to undergo the long, uncertain, and public process of being such a test. The ACLU had nearly given up hope when they received Mildred Loving’s letter and accepted the case despite the black-white pairing.

Like the South’s response to landmark civil rights rulings before it, little changed immediately after the Supreme Court decision on Loving in June 1967. Most southern states continued to resist the court’s decree and placed the burden on couples to appeal to federal courts if denied marriage licenses.

A county clerk in Tennessee stalled marriages by insisting that he could not issue licenses to interracial couples until personally receiving a copy of the Supreme Court ruling. Federal judges had to force Delaware, Louisiana, and Arkansas to issue licenses in 1967 and 1968. A Mississippi state judge issued an injunction to prevent an interracial couple from marrying in 1970. Although Virginia began issuing licenses to interracial couples, it continued to issue pamphlets stating that interracial marriage was illegal.

Although some states repealed their marriage bans within a year or two of the Loving decision, others stretched the process out. Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, North Carolina, and Tennessee repealed their bans during the 1970s while Delaware waited until 1986 and Mississippi, 1987.

Two states and at least one official, however, outlasted all others. South Carolina and Alabama kept their bans until 1998 and 2000, when referendums removed them—but even then, 38 and 40 percent of voters opposed repeal. In 2009, a Louisiana Justice of the Peace resigned after being told he could not continue to refuse to marry interracial couples.

Guess Who’s on the Cover of Time

Despite the white South’s intransigence, just months after the Loving decision, two other events cemented 1967 as a momentous year for interracial marriage and for shaping the public’s views on it. In September 1967, Peggy Rusk—the white daughter of Secretary of State Dean Rusk—and Guy Smith—a black Georgetown graduate student—married. In a move unthinkable a few years earlier, Time ran a photo of the newlyweds on its cover and celebrated their union as “a marriage of enlightenment.”

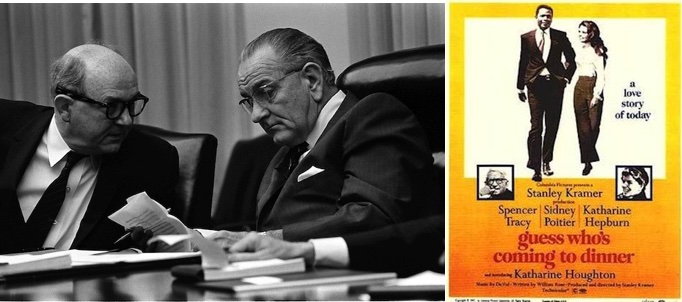

Secretary of State Dean Rusk with President Lyndon Johnson in 1968, the year after he offered his resignation because his daughter, Peggy Rusk, planned to marry Guy Smith, a black graduate student (left). The movie poster for the 1967 film Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner (right).

Just a few months after that, a comedy-drama hit theaters staring three of Hollywood’s biggest stars. Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner centers on a white woman bringing her black fiancé home to meet her parents. Her liberal parents’ ideals are tested, but ultimately conclude that the pair are “two wonderful people… who happened to fall in love” and give the union their blessing. As the year’s most talked-about film and one of the first respectful onscreen portrayals of an interracial couple—even if the film made Sidney Poitier’s character too perfect and whitewashed white racism—it did much to nudge public opinion towards acceptance.

The first film about an interracial romance, D. W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919), used a white actor to portray a Chinese man in love with an English girl (left). Like many films that would follow on interracial romance, it ended in tragedy. The Motion Picture Production Code prohibited the depiction of interracial romances until 1956. Hollywood circumvented the prohibition by casting white actors for nonwhite roles so relationships would not technically be interracial. Island in the Sun (1957) featured the first actual onscreen kiss between a black actor and a white actor, to much public controversy (right).

Rising Rates, Persistent Attitudes

Nevertheless, public opinion proved slow to change in the coming years, especially for black-white pairings. In 1990, 63 percent of non-blacks said they would oppose a close relative marrying a black person. Rates of disapproval for a close relative marrying a Hispanic or Asian person—more often seen as cross-cultural marriages than cross-racial ones—were far lower.

Regardless of the type of interracial pairing, though, not until 1997 did a majority of Americans express approval of interracial marriages. Since then, approval has increased exponentially. In 2013, the last year Gallup bothered to ask, 87 percent of Americans approved.

Interracial marriage rates have also vastly increased in recent years. One out of every six newlyweds today marries someone of a different race. Over a quarter of all Latinos and Asians marry interracially, a figure that nearly doubles when only including those born in the United States. Interracial marriage rates are far lower for black-white unions, but they have seen the most dramatic growth in the rate of intermarriage—more than tripling from 5 percent in 1980 to 18 percent of black newlyweds today.

A chart depicting falling American support for interracial marriage prohibitions from 1972 to 2002.

Although considerably higher than even a few years ago and incomparable to the miniscule rates before Loving, intermarriage rates are still relatively low—especially between blacks and whites. If Asians and Hispanics are removed from intermarriage figures, intermarriage rates remain extremely low. White opposition to a close relative marrying a black person has decreased dramatically, but still constitutes 14 percent of white views in 2017.

These rates of marriage and disapproval speak to more than just continued individual discrimination. They also reflect the larger structural barriers that remain entrenched and that interracial marriage bans helped build. Many schools, workplaces, and communities in the United States remain highly segregated and therefore offer few opportunities for blacks and whites to meet and marry.

Even as some pundits began to discuss America as a post-racial society in the early Obama years, a seemingly benign cereal commercial revealed both the ugliness of the anonymity of the internet and the staying power of virulent opposition to interracial pairings.

|

The 2013 Cheerios commercial featuring a biracial family garnered so many hateful YouTube remarks that the company closed the comment section. Harkening back to the nation’s long history of hysteria over interracial pairings, many commenters described the commercial as “disgusting” and “vomit” inducing. Others hatefully reveled in racial stereotypes by suggesting that the black father would beat or abandon his white wife. Although the majority of comments were positive, the amount and strength of the vitriol underscores the lingering public opposition and its deeply ingrained nature.

For those who were surprised by the vitriol surrounding the Cheerios ad, a 2017 film illustrates how continued racism against African Americans and interracial couples is often more subtle, if no less harmful. Jordan Peele’s satirical dramedy Get Out is perhaps today’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, except it’s a horror film. A surprise mega-hit, Get Out’s witty examination of microaggressions and use of race to subvert horror tropes has resonated at the box office and to critics alike.

Like its predecessor fifty years earlier, Get Out features white liberals with seemingly the best of intentions (“If I could, I would have voted for Obama for a third term” declares the white father to his daughter’s black suitor by way of introduction). Albeit ad absurdum, Get Out showcases the continued barriers to interracial intimacies and how fraught the wider public and the closest family can make these relationships.

Celebrating Loving, Forgetting its History

Loving ranks as a seminal Supreme Court decision and a vital civil rights victory. For three centuries, white America held interracial marriage bans fundamental to national identity and vital for building and policing racial boundaries. But despite the tremendous amount of progress since Loving, wide societal disparities remain as the structures marriage bans fostered still persist.

The 2016 Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania commissioned 57 fiberglass donkeys painted by local artists to represent each delegation to the convention. Virginia’s featured George Washington, Richard and Mildred Loving, and the state’s slogan since two years after the Loving ruling, “Virginia is for Lovers.”

Today the nation celebrates Loving as an example of racial transcendence and prejudice squashed. The Loving ruling can and should be celebrated as a momentous achievement. It not only led to the end of interracial marriage bans in 16 states, but more recently aided the Supreme Court’s decision in Obergefell v. Hodges, which legalized marriage for same-sex couples. A celebration of Loving, however, should not push out of public memory the three-centuries-long prohibitions on interracial marriage and their painful ramifications.

Carter, Greg. The United States of United Races: A Utopian History of Racial Mixing. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

Cashin, Sheryll. Loving: Interracial Intimacy in America and the threat to White Supremacy. Boston: Beacon Press, 2017.

Hodes, Martha, ed. Sex, Love, Race: Crossing Boundaries in North American History. New York: New York University Press, 1999.

Hodes, Martha, White Women, Black Men: Illicit Sex in the Nineteenth-century South. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997.

Lemire, Elise, “Miscegenation”: Making Race in America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002.

Maillard, Kevin Noble and Rose Cuison Villazor. Loving v. Virginia in a Post-Racial World: Rethinking Race, Sex, and Marriage. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Nyong’o, Tavia. The Amalgamation Waltz: Race, Performance, and the Ruses of Memory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Pascoe, Peggy. What Comes Naturally: Miscegenation Law and the Making of Race in America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Rosen, Hannah. Terror in the Heart of Freedom: Citizenship, Sexual Violence, and the Meaning of Race in the Postemancipation South. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Wallenstein, Peter. Tell the Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law: An American History. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002.