On April 4, 1968, at 6:01 pm, James Earl Ray, a white drifter and petty criminal, raised a bathroom window at the rear of Bessie Brewer’s Rooming House on South Main Street in Memphis, TN and aimed a Remington Model 760 rifle across the street at the Lorraine Motel. When he saw Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. step onto the balcony of room 306, he pulled the trigger. A fraction of a second later, a single .30 caliber bullet from his weapon struck the civil rights leader in the head. At 7:05 pm, doctors at St. Joseph’s Hospital pronounced Dr. King dead. He was 39.

As word of the tragedy spread throughout Memphis, a pall of shock and sadness blanketed the black community. Anguish soon turned to anger. Fearing a riot, the Memphis police went on high alert. But calm prevailed. Local civil rights activists, who for the past two months had been leading a full-scale grassroots mobilization to support striking black sanitation workers, channeled raw emotions into peaceful marches and public remembrances.

Nonviolence, however, did not win out everywhere. 172 American cities exploded in the days following Dr. King’s assassination. In communities large and small, stretching from the East Coast to the West, African Americans poured into the streets to vent their rage. In almost every instance, they targeted local symbols of white supremacy. In Washington, D.C., which experienced some of the worst unrest, African Americans torched white owned businesses and clashed with police.

Although Dr. King had fallen out of favor with many African Americans who felt that nonviolence had run its course both tactically and philosophically, they still respected him. They may have disagreed with his approach, but they admired his commitment to social change. They may have felt that his tactics needlessly put people in danger, but they did not doubt his courage. So when they heard the news that he had been murdered, they were enraged, furious at white America for silencing a voice of compassion and love. Dr. King had preached peace and had been cut down by violence. And so it had to be the fire this time.

Damage to a store following riots in Washington, D.C.

The disturbances following Dr. King’s death are often dismissed as chaotic outbursts of violence from emotionally distraught black mobs, with more than a few criminal opportunists among them. But they were much more than that. They were rebellions against the racially discriminatory status quo, attempts by an especially alienated segment of the black population (impoverished and unemployed young men) to make white America take notice of their plight, of their deep frustration, and of their determination to do something about their situation. These were protests about police harassment, housing segregation, inadequate municipal services, failing schools, and nonexistent jobs.

The looting that took place during these uprisings reflected these sentiments, as those who perpetually did without seized the opportunity to cast aside normative expectations of black consumers—that they pay more for less—to acquire necessities they always struggled to afford and luxuries they never could. For some, it was retribution. For others, it was reparations.

The impact of the rebellions was long lasting. Whites had been fleeing America’s central cities for newly developed, lilywhite suburbs for two decades, but the uprisings quickened the process in some places, while completing it in others. The absence of whites eroded a tax base that was already in steep decline, exacerbating the problem of poor municipal services and insufficient social services.

Garment workers listen to the funeral service for Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on radio, April 1968.

Companies had been doing the same thing - chasing corporate tax breaks designed to lure them away from urban centers. The rebellions increased the resolve of many to leave and hastened the departure of quite a few others. The relocation of large companies was especially harmful. The absence of capital investors made short-term recovery from the physical destruction wrought by the rebellions extremely difficult, and the permanent loss of jobs made sustaining long-term recovery efforts almost impossible. The disappearance of small mom and pop shops, many of which did not reopen after being burned, hurt as well by further limiting consumers’ options.

The clashes with police had far reaching consequences too. They significantly aggravated already tense relations between the police and the black community, which continued to deteriorate in subsequent years as the officers and command structure of metropolitan police departments remained overwhelmingly white despite rapidly changing racial demographics.

Dr. King’s death and the uprisings that followed did more than just reshape American urban landscapes. They also determined how Dr. King has been remembered, or more accurately, misremembered.

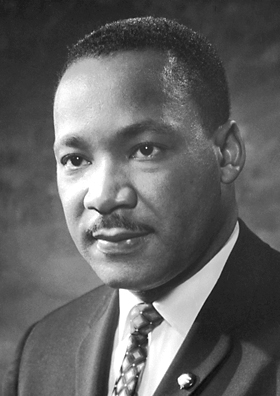

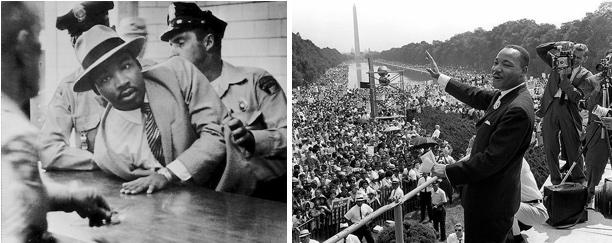

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. being arrested in Montgomery, Alabama in 1958 (left), and Dr. King speaking at the March on Washington in August 1963 (right).

Today we celebrate Dr. King for his remarks at the 1963 March on Washington, but at the time he was denounced across the South as a communist sympathizer, and roundly criticized throughout the North for pushing for civil rights too hard and too fast. And in 1967, when he finally spoke out against the war in Vietnam, he was pilloried by liberals for not knowing his place – “stick to civil rights,” they said – and he was excoriated by southern segregationists and northern “law and order” conservatives for being a radical extremist.

All this began to change when Dr. King fell to an assassin’s bullet. The day before, he was persona non grata at the White House because of his opposition to the war in Vietnam. The day after, President Lyndon B. Johnson praised him in a presidential proclamation as a “teacher of all people” whose “vision of brotherhood” gave purpose to his “life and works.” To paraphrase the poet Carl Wendell Hines, now that Dr. King was safely dead, it was time to praise him, to build monuments to his glory, to sing hosannas to his name.

Lyndon B. Johnson addressing the nation on April 4, 1968. (Video from ABC News)

Even before his funeral had taken place, the public process of reimagining Dr. King as a colorblind crusader determined to end racial discrimination without using race-conscious approaches to change had begun. And by 1983, when President Ronald Reagan signed the bill making his birthday a national holiday, the American prophet of nonviolence had been reduced to a handful of sound bites from the March on Washington and snippets from his Letter from Birmingham Jail.

Dr. King’s politics had not changed. People just chose to ignore his critiques of capitalism, militarism, and racism in the interest of making him more palatable to white Americans. In many ways, the man we celebrate today is not the man who lost his life on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in 1968.

As public perceptions of Dr. King’s politics changed, so too did general understandings of the civil rights movement. Those who had identified Dr. King as the singular leader of the movement while he was alive declared the movement over when he died.

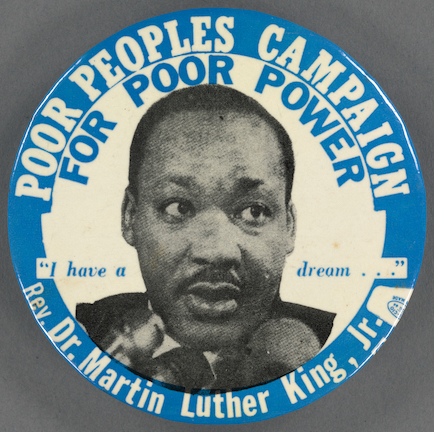

A pin for the Poor People's Campaign showing Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., 1967-1968.

But the movement Dr. King helped shepherd to new heights in the 1950s and 1960s did not suddenly end in 1968. Activists close to the “drum major for justice,” from his wife Coretta Scott King to his successor at the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) Rev. Ralph David Abernathy, continued the march for freedom. So too did those who did not know him well or did not know him at all. They continued agitating for nondiscrimination in employment and housing, desegregation and community control of schools, and equal protection under the law. And they did it with even more passion and determination than before, with raised clenched fists and shouts of Black Power!

These activists won notable victories in Dr. King’s name immediately after his death, including a resolution of the Memphis sanitation workers’ strike and passage of the 1968 Fair Housing Act. But they also met continued resistance. The participants in the Poor People’s Campaign, Dr. King’s final crusade to get the nation to address its appalling levels of poverty, were put out of Washington, D.C. in June 1968 having failed to persuade federal officials to act. The assassination of Dr. King neither ended the movement, nor made it any easier.

It has been more than fifty years since Dr. King was shot and killed and the nation is still wrestling with the meaning of his life and death. One thing is for sure. Dr. King was a man ahead of his time, and not even our time has caught up with him yet.