In November 2018, voters in Florida voted overwhelmingly to restore voting rights to citizens with criminal records. In Spring 2019, the Republican-controlled state legislature moved aggressively to subvert the intent of that referendum. This was only the most recent fight over whether those convicted of crimes should be barred from voting. But as historian Pippa Holloway explains, this debate stretches all the way back to the Civil-War era and is inextricably bound up with attempts to control African American voting. Disfranchised voters are another of slavery's long shadows cast on American politics.

In November 2018, voters in Florida approved a ballot initiative that amended the state's constitution to give the vote back to citizens who had lost the right because of a criminal conviction. Passing with a 64% majority, the amendment restored voting rights to ex-felons who had completed their prison sentence and been released from parole or probation, except for those convicted of murder or felony sex crimes.

A variation on an “I voted” sticker to raise awareness of those who are not allowed to vote.

Most Americans agree with voters in Florida that those who have "done their time" should no longer be punished with disfranchisement. Nonetheless, 6 million citizens, 2.5% of the voting age population, still cannot vote due to a felony conviction. Of that 6 million, 4.7 million are no longer incarcerated.

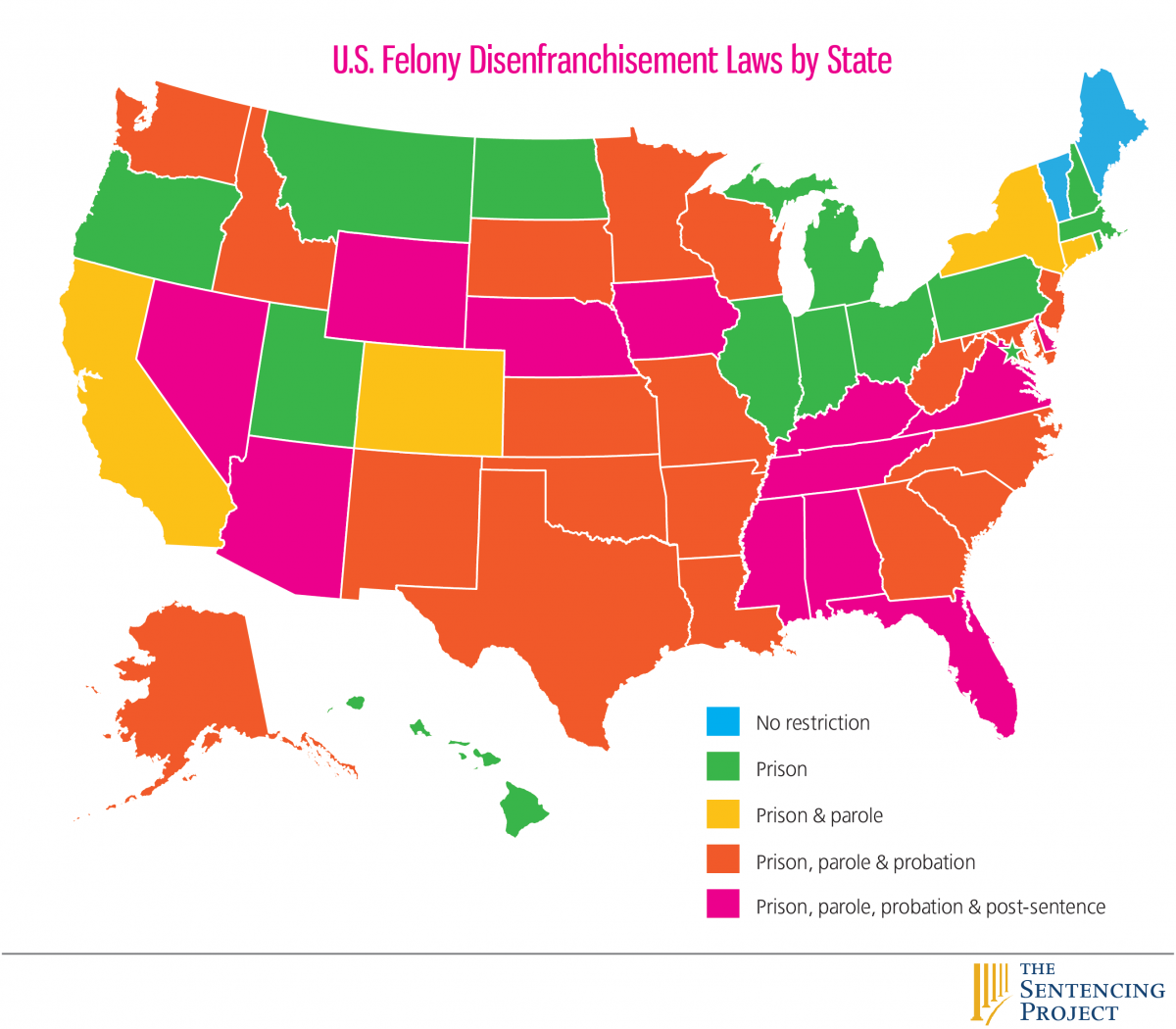

Some of these individuals live in states, such as Kentucky and Tennessee, which maintain laws like the one Floridians voted to eliminate. More common are states that extend disfranchisement through probation and parole, sometimes also requiring the full payment of court fines and fees, what some see as a modern poll tax. For many ex-offenders, clearing all of the obstacles necessary to vote again can take years or even a lifetime.

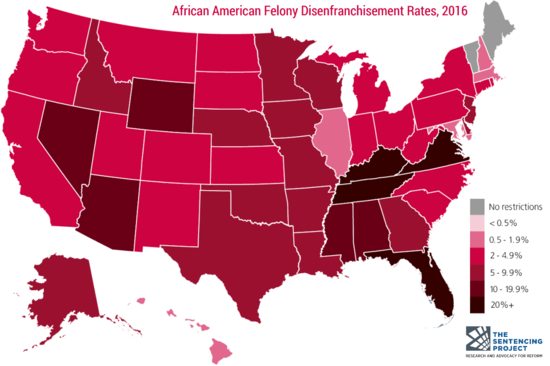

Unmistakably, felon disfranchisement has a racial and regional pattern. These laws disproportionately affect African Americans across the nation and southern states are much more likely to impose long, post-incarceration disfranchisement. Four southern states deny the vote to a staggering 20% or more of the black population: Florida (21 percent), Kentucky (26 percent), Tennessee (21 percent), and Virginia (22 percent).

How did we get here? Why does the United States have laws that deny significant numbers of Americans one of the most important constitutional rights? Why do these laws disproportionately affect African Americans, and why are the most draconian limitations on suffrage found in the South?

Answers to these questions can be found deep in America’s complicated histories of slavery, segregation, and mass incarceration.

Before the Civil War

Laws denying rights and privileges of citizenship to those convicted of certain criminal acts have long existed in the western world. In fact, such practices date back to ancient Greece and Rome and have antecedents in early modern European law as well as in English common law. By the 1830s, most U.S. states had laws disfranchising people convicted of major crimes.

Northeastern and southern states, however, differed in the early 1800s. New Englanders opposed these laws and limited their scope. Representatives in Maine rejected a proposal for felon disfranchisement in 1819. New Hampshire and Massachusetts had no such provisions during this period. In 1832, the Vermont legislature eliminated a criminal disfranchisement provision that dated back the early days of statehood.

These laws were more common in the mid-Atlantic region, but they still faced opposition and were often watered down. Pennsylvania rejected felon disfranchisement in the 1830s and passed a limited version that temporarily disfranchised only some offenders in 1873. Maryland enacted felon disfranchisement in 1850 but only after an acrimonious debate.

A 2016 map of felony disfranchisement laws by state [courtesy of The Sentencing Project].

In contrast, southern states uniformly enacted sweeping provisions permanently disfranchising for infamous or major crimes in this period, and there is little evidence of dissent or debate over this in the South.

In all regions of the United States, however, disfranchisement for crime seems to have been used sparingly before the Civil War. Only those convicted of major crimes lost the right to vote. The number of individuals these laws affected was small because convictions for these serious crimes were rare.

Racial Disfranchisement after the Civil War

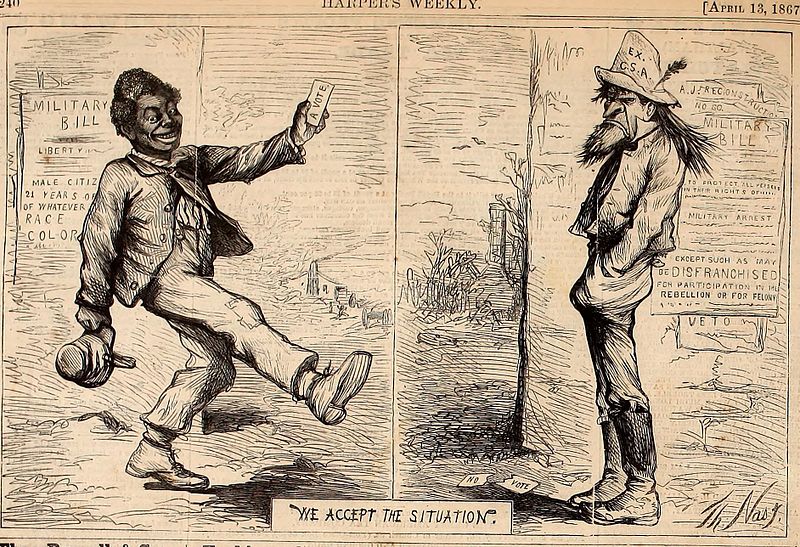

In 1866, for the first time, black and white men elected representatives for constitutional conventions in every state of the former Confederacy. The Civil War had just ended, the 13th Amendment outlawed slavery in 1865, and the 14th Amendment—promising citizenship and equal protection—would soon be ratified (1868).

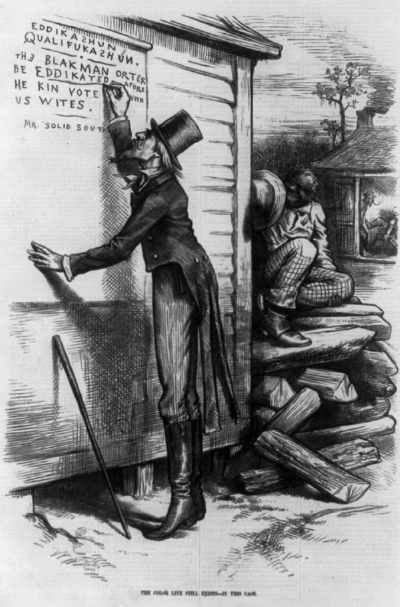

An 1867 cartoon depicting an enfranchised black man and a sulking Confederate.

Desperate to stop black voting in order to maintain their racial hierarchies and privileged positions, white southern Democrats would soon turn to legal tools such as literacy tests and poll taxes to limit black suffrage, but the first methods they turned to after the war were existing laws disfranchising for crime.

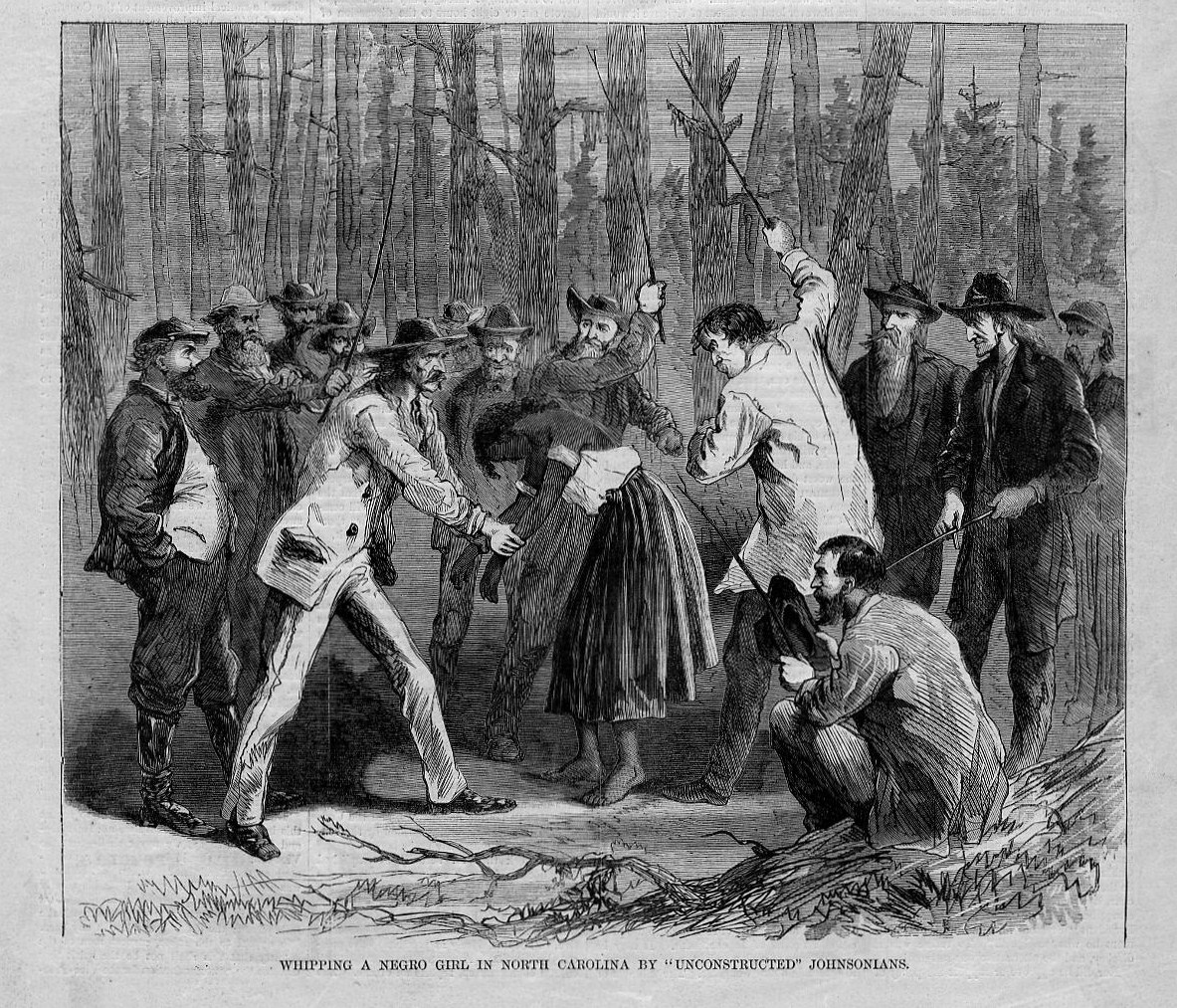

Arguably, North Carolina was ground zero for these efforts. White Democrats there undertook a campaign of mass whippings of black men. The Atlantic Monthly explained why: “The public whipping of negroes for paltry offences is carried on in North Carolina on a large scale, for the reason that by the laws of that State every man who has been publicly whipped is excluded from the right of voting.”

According to congressional testimony, Democrats celebrated that the whipping campaign enabled them to “head off Congress from making the negroes voters.” One legislator stated, “We are licking them in our part of the State and if we keep on we can lick them all by next year, and none of them can vote.”

Similar developments occurred in other southern states. Reconstruction officials were able to protect black voting rights for a few years, but as federal authority declined in the region in the early 1870s, southern whites’ pushback against voting rights re-emerged and targeted African Americans.

The 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870 partially as a response to southern states’ suppression of the black vote, declared that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” Nevertheless, states found a variety of creative ways to deny black men the right to vote.

Crimes of Infamy

Recently, the debate over felon disfranchisement has focused on those guilty of the most “infamous” crimes—shocking deeds or tragic events such as the Boston Marathon bombing. Dating back to English and continental European law, however, “infamy” came not from the crime itself but from the punishment for a crime. Public and degrading punishments lowered social status, and thereby were thought to deprive those subject to such punishments of the respect due to citizens.

An 1867 depiction of a black woman being whipped in North Carolina.

This historical notion of infamy explains North Carolina’s mass whippings. A belief that infamous punishment brought about degradation and loss of citizenship was why whipping to disfranchise was the first thing that white Democrats in North Carolina undertook in their desperation to block African Americans from voting.

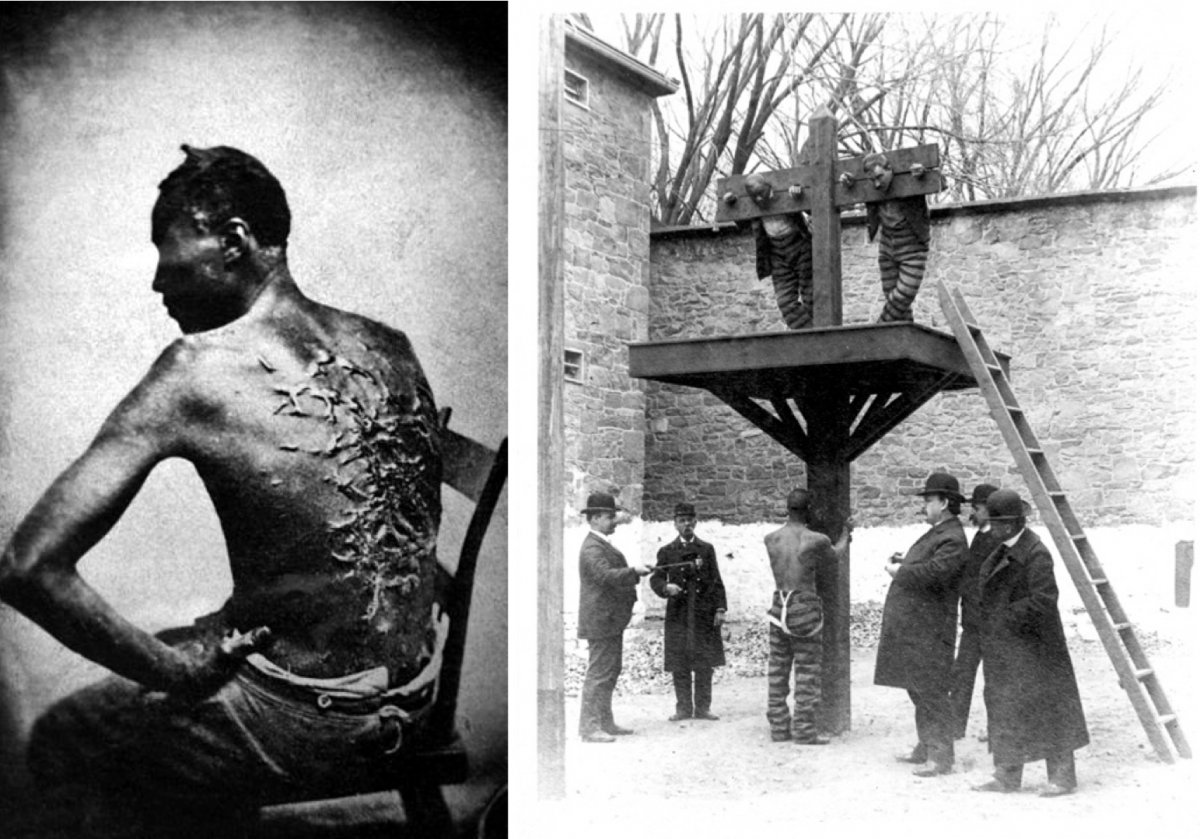

Infamy connected one’s legal status to one’s social status, and these connections were particularly evident in the slave-era South. Public humiliation was a regular aspect of life for slaves, whether it was on the auction block, through brutal physical punishment that left permanent scars, or in the daily degradation of being a captive. Whites on both sides of the abolition issue frequently used the specific word “degraded” to describe African Americans throughout the 19th century. Enslavement, they believed, produced a degraded race.

An infamous depiction of a Louisiana slave in 1863 with scars from numerous whippings (left). A Delaware whipping post and pillory around the turn-of-the-century (right).

“Degraded” was also a term used to describe convicts, particularly those who had faced brutal public punishment. The cultural and legal status of enslaved people and convicts were conjoined. Enslaved people were seen as degraded because they were like prisoners; and prisoners are degraded when they are like slaves.

These connections were particularly visible to white southerners, many of whose privilege depended on the degradation and humiliation of others. Moreover, the connection between infamy and slavery helps explain why people in southern states were more likely to disfranchise people with felony conviction in the early 19th century while citizens of northern states were more skeptical of this practice.

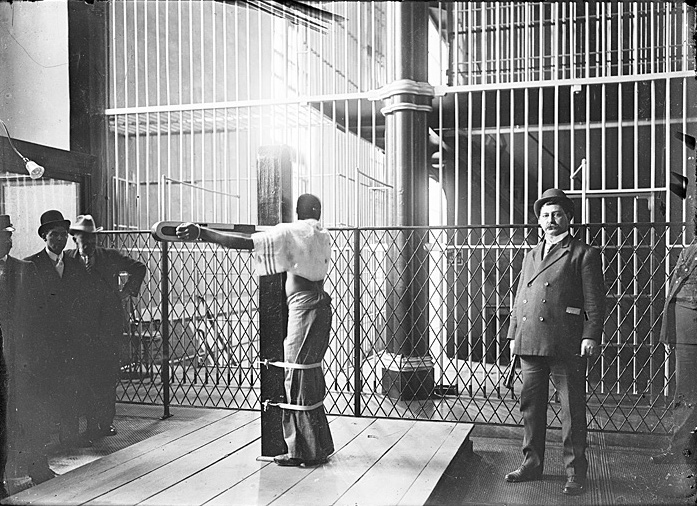

A whipping post in a Baltimore City Jail used from 1865 to 1938 [McFee Photography Collection].

Even though the 13th Amendment (1865) abolished slavery, many white southerners did not believe that the stain and degradation of slavery could or should be lifted. They saw an opportunity to re-establish the legal infamy of African Americans by whippings, as well as through other acts of violence and terror that denied African Americans their rights.

Brutal, humiliating but legal punishments could make their victims infamous because, the law held, infamous punishments (not infamous crimes) made people degraded and unfit for citizenship and thus for voting.

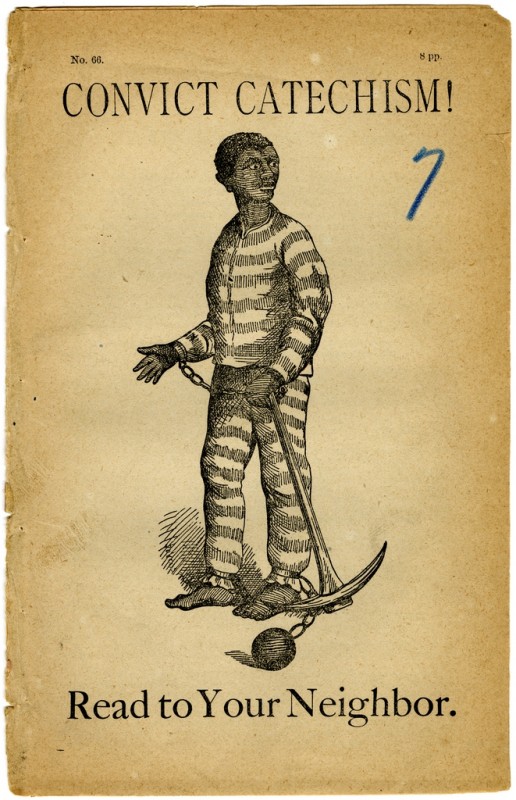

“A Chicken-Stealer Shall Lose His Vote”

In the 1870s, every state under Reconstruction except Texas changed its laws to deny the vote to individuals convicted of petty theft and misdemeanor larceny—a change consciously designed to remove black voters from the rolls.

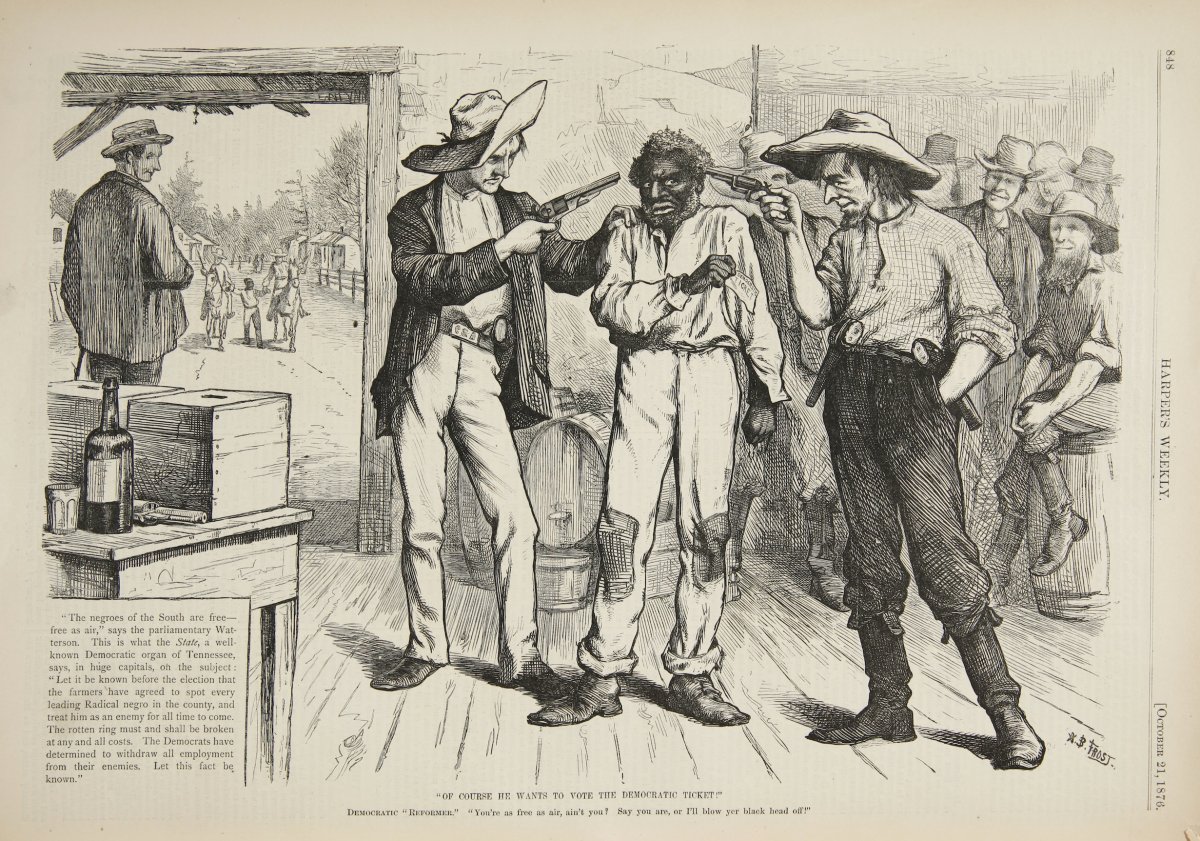

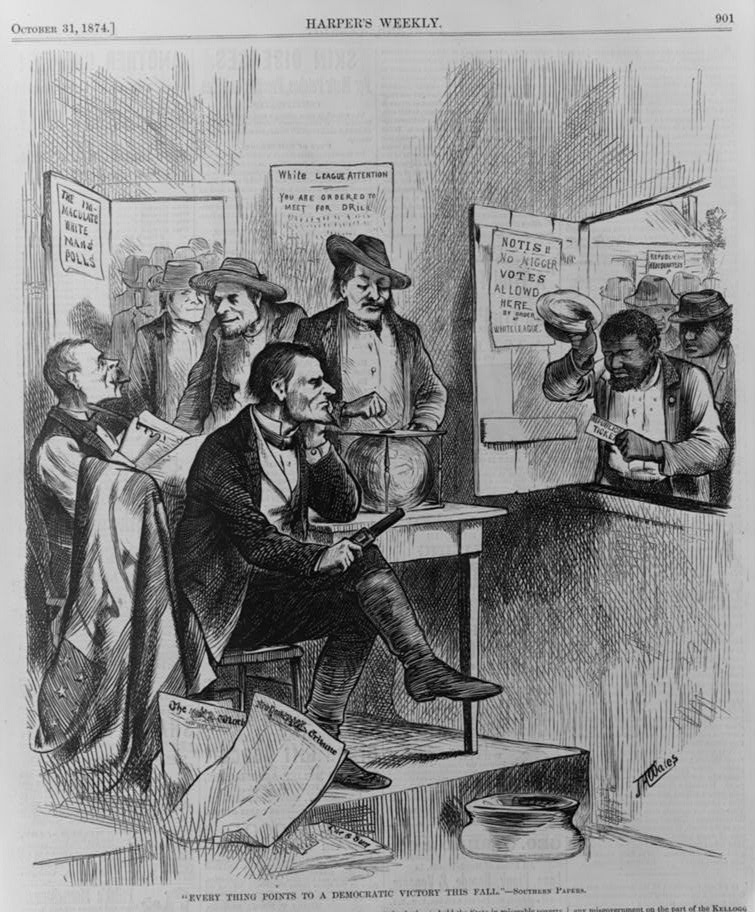

An 1876 cartoon depicting intimidation of an African American voter.

In addition to imposing a poll tax, for example, Virginia changed its constitution in 1876 to denying the vote to individuals convicted of small property crimes. In other states, court decisions determined that statutes disfranchising for larceny included all grades of larceny, both felony and misdemeanor.

Another approach was to pass legislation to lower the bar for felony theft. Between 1874 and 1876, four southern states—Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, and Georgia—significantly expanded the definition of felony to include property offenses previously defined as misdemeanors.

Mississippi’s 1876 “Pig Law” is perhaps the best known of these. Mississippi law had defined grand larceny (a felony) as the theft of anything valued at more than $25. The Pig Law broadened the definition of grand larceny by reducing to $10 the value of stolen goods needed to trigger this felony-grade offense. In addition, the new law defined the theft of certain livestock as grand larceny, even if the property was worth less than $10. As a grand larceny conviction brought disfranchisement, the law’s advocates acknowledged at the time and celebrated that this was the intent of the bill.

With the clear racial and partisan implications, these disfranchisement penalties were often implemented right before an election. If a close election was coming up, prosecutors would step up efforts to charge would-be African American voters with theft. All-white juries or racially motivated magistrates would convict black men who were registered to vote of minor property crimes.

A well-documented example occurred in 1880 in Ocala, Florida. A black man named Cuffie Washington testified to Congress that when he tried to vote in the congressional election, Democrats challenged his right to vote because, they said, he had stolen three oranges. Washington conceded that he had been convicted of such a crime about a month before the election. Such charges, he said, had become more frequent “because the election was close on hand.”

A depiction of convicts in the South in the 1870s.

Like Washington, several other black men in Ocala and Marion counties testified that they were disfranchised that day for having stolen a gold button, a case of oranges, hogs, oats, six fish (worth 12 cents), and a cowhide. Allen Green, one of the alleged hog thieves, confirmed Washington’s analysis: “It was a pretty general thing to convict colored men in that precinct just before an election; they had more cases about election time than at any other time.”

Supporters celebrated these laws and even joked about them. An 1875 editorial in the Richmond Daily Dispatch jeered at black political activists who challenged these laws: “A sapient member of the negro convention in this city is shocked at the idea that a chicken-stealer shall lose his vote.”

These developments astounded some elected leaders outside the South. When an Alabama Democrat testified before Congress in 1877 that petty larceny could bring disfranchisement, an incredulous senator asked for clarification. “For instance, if a man steals this pen … worth one cent, and is convicted of it, he is disqualified from voting under the constitution of Alabama?” The answer was yes.

In 1888, Democrats in Richmond, Virginia, drew on that state’s law prohibiting those convicted of misdemeanor larceny from voting when they came up with a plan to help their incumbent defeat his Republican challenger in the city’s congressional election. On Election Day, the party stationed “challengers”—official partisan election monitors—at the city’s three predominantly African American precincts, where they spent the day questioning voter eligibility. Only African American voters underwent this interrogation.

One particular kind of challenge took a disproportionate amount of time: would-be voters who were accused of having a prior criminal conviction had their names checked against long lists of those convicted of disqualifying crimes. Because segregated precincts had separate lines for the two races, white voting proceeded apace while African Americans waited for hours.

It is impossible to know how many people were affected by these challenges and resulting slow-downs at the polls. More than 500 black men were still waiting in line to vote when the polls closed and untold numbers had given up earlier because of the long wait. Others likely decided not to vote because they feared harassment at the polls. Beyond simply denying the vote to ex-offenders, these laws eroded the African American electorate through intimidation and delays.

An 1874 depiction of discrimination against would-be black voters by the “White League.”

Disfranchisement Goes North

As African Americans migrated out of the South in growing numbers in the 20th century, disfranchisement laws migrated with them.

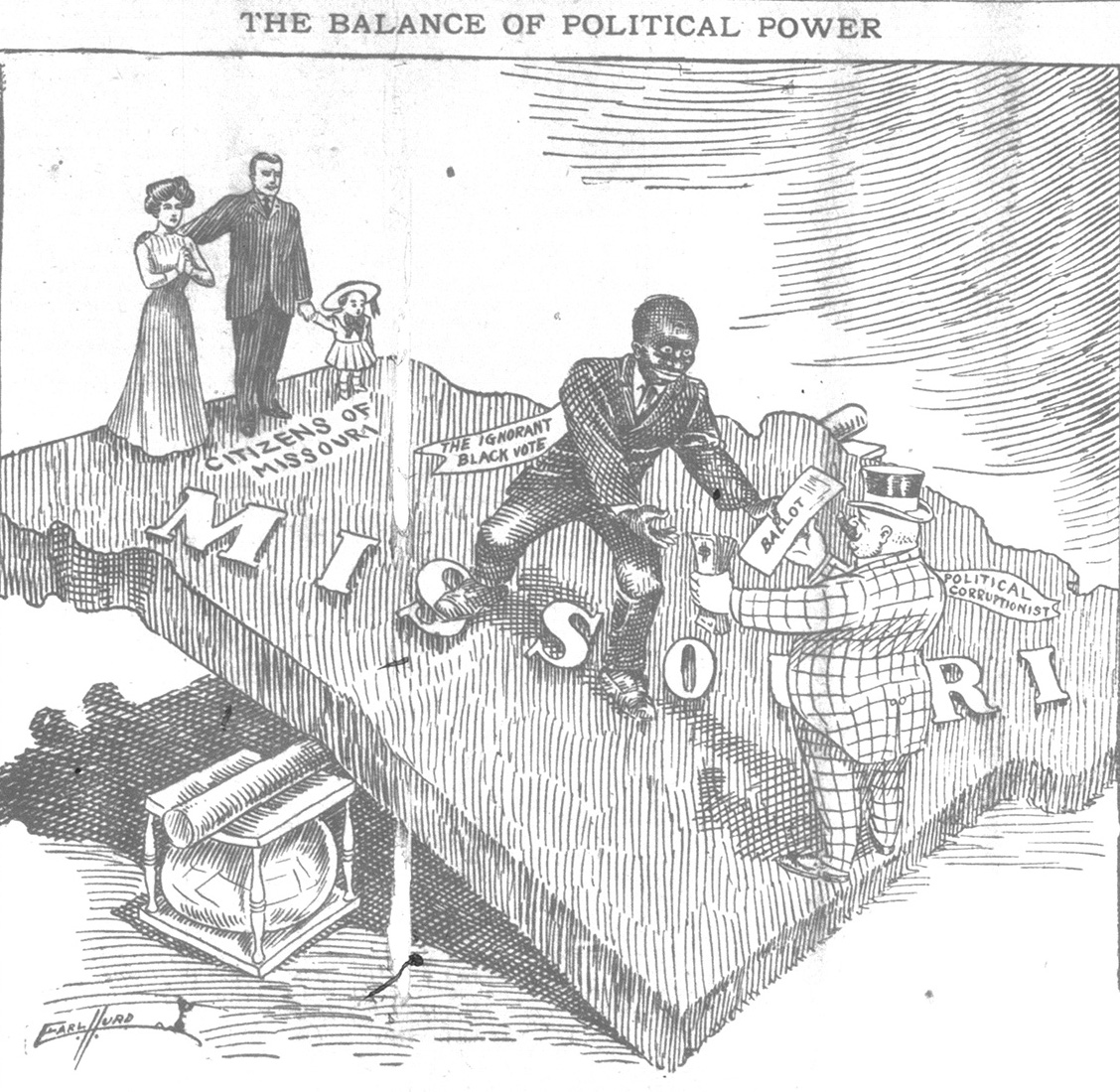

During the 1916 election in St. Louis, Democratic Party operatives sought to intimidate African American voters, many of whom had migrated to the city in the past decade, with threats of criminal penalties for ex-offenders who voted. A few weeks before the election, Democratic leaders dispatched about 20 young attorneys to comb the criminal court records and amassed a list of approximately 3,000 African Americans who had been convicted of a crime, about 25 percent of the city’s registered black voters.

A 1908 cartoon depicting African American voters in Missouri as susceptible to corruption.

Then the day before the election, the Democratic Party took out an ad warning black voters:

Democratic challengers in every affected precinct in the sixteen wards have been given a list of the negroes who have registered illegally. AS RAPIDLY AS THEY ARRIVE AT THE POLLS THEY WILL BE CHALLENGED. IF THEY INSIST ON CASTING THEIR BALLOTS AND START TO SWEAR IN THEIR VOTE, THEY WILL BE ARRESTED AT ONCE, CHARGED WITH PERJURY.

On Election Day, St. Louis Democrats stationed “challengers” in black precincts and challenged would-be black voters. Some gave up and left as soon as a challenge was issued. In some precincts, police arrested black men immediately after they were challenged. In other instances, they waited until a vote had been cast before making an arrest. Police escorted others out of the polling place without arrest but prevented them from voting. In all, 96 African Americans and two whites were arrested for allegedly trying to vote despite disfranchising convictions.

Mass Incarceration and Mass Disfranchisement

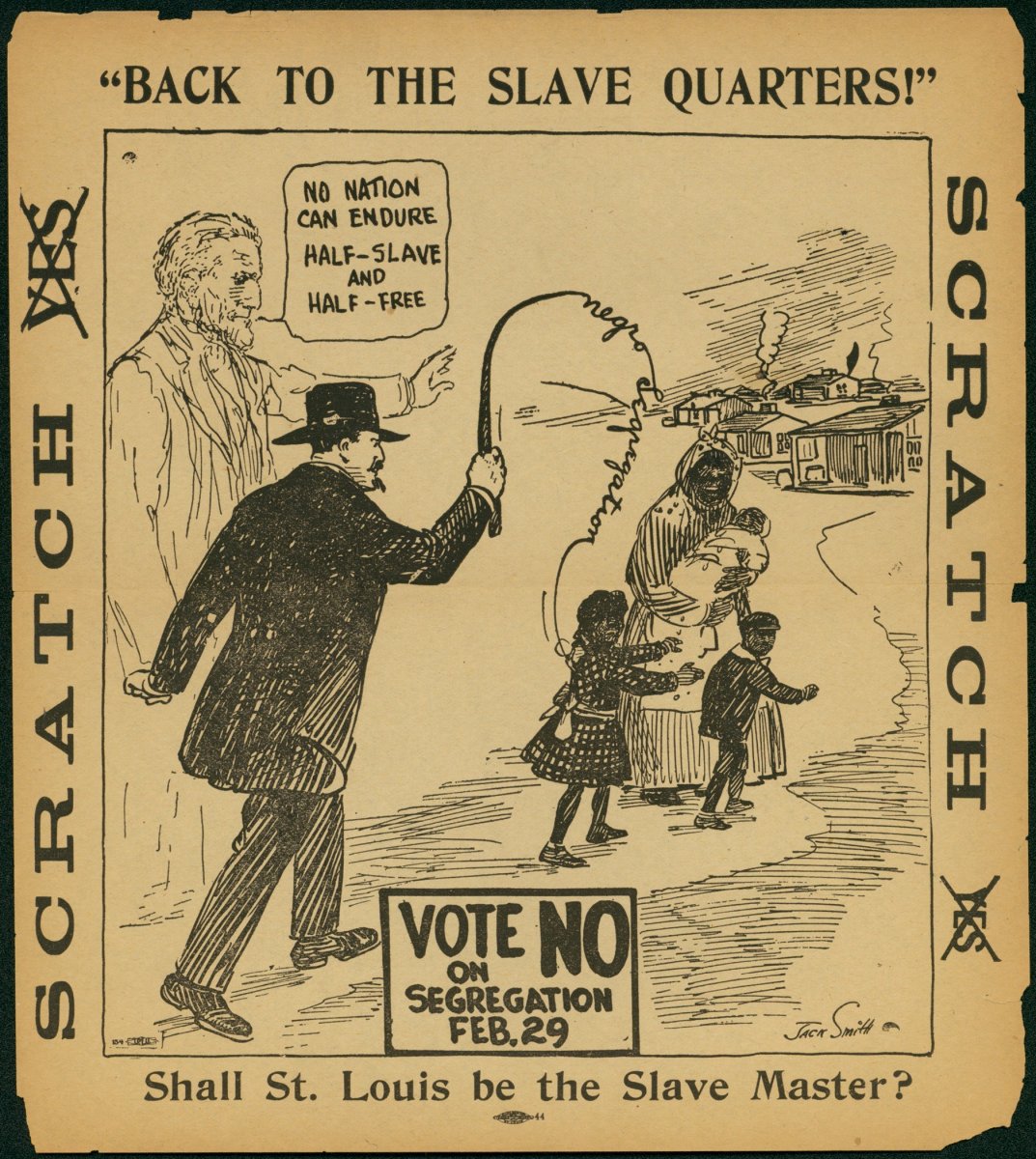

A St. Louis newspaper described the election-day arrests and harassment of black voters as “an effort to Southernize the ballot.” Indeed, the whole nation experienced this kind of southernization in the 20th century, as some of the rationales and practices of the slave South were instilled in the nation’s criminal justice system.

In the mid-19th century, some northern states had been resistant to the cultural and legal logic of infamy, believing instead that convicted individuals could be “fixed” and returned to full citizenship. Increasingly brutal prison conditions and a nationwide embrace of convict labor began to shift attitudes toward incarceration.

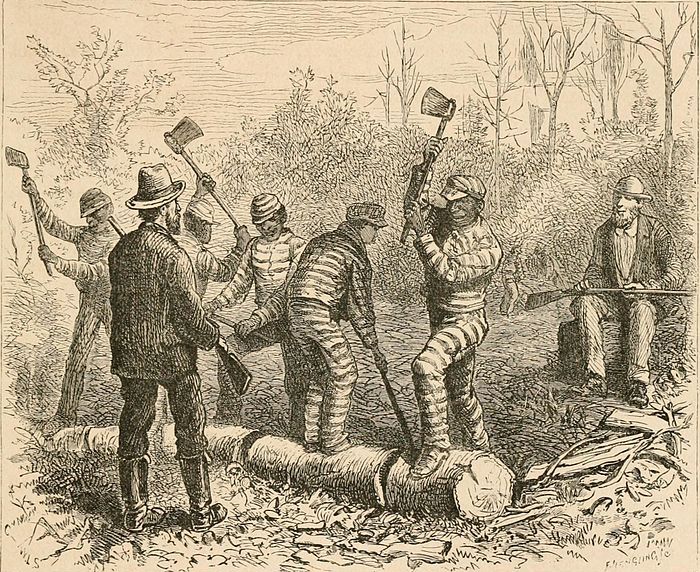

Prisoners performing fieldwork in Mississippi around 1911.

Prisons in the South and, increasingly, the whole nation, were places of labor. Rather than spending public money on mental health treatment and education for prisoners, states could generate revenue and save money by putting prisoners to work. Prisoners lived and worked in ways that resembled slavery.

This added up to a nationalization of the southern idea that all of those who were incarcerated, regardless of their race, were a degraded “other” marked for life by their punishment. Putting convicts to work on behalf of the state, or selling their labor to manufacturers, became a national phenomenon.

This practice is still in use today as prisoners make up about a third of those doing the dangerous work of fighting forest fires in California, where they are paid $1/hour. Nationally the average pay in state prisons is 20 cents/hour.

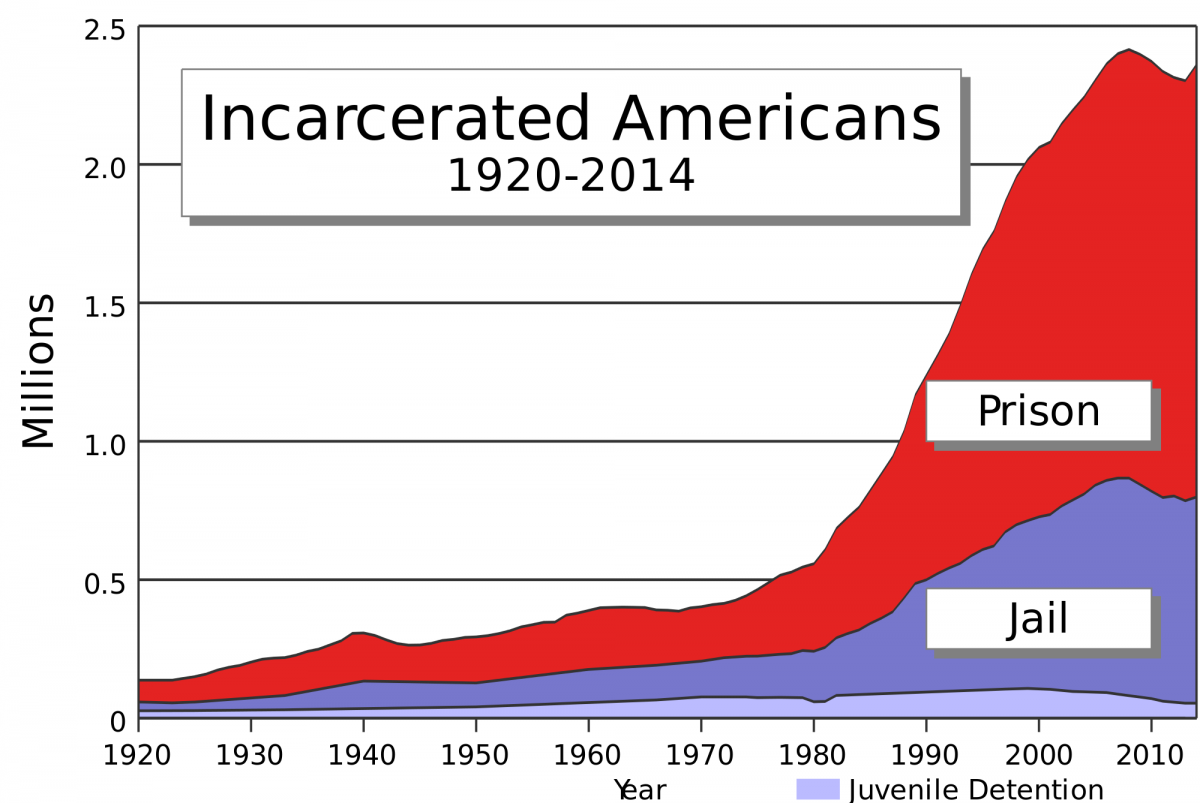

Under a growing system of mass incarceration, the U.S. criminal justice system reaches into the lives of an expanding share of the population. By the end of the 20th century, the United States had the highest rate of incarceration and the world’s largest prison system.

Mass incarceration did not just mean expanding the number of people locked up; it also made a growing part of the population infamous and therefore disfranchised. Whereas felon disfranchisement laws had previously affected a small part of the population, the numbers of people losing their voting rights expanded as felony convictions increased and spread to more states.

All of the new states added to the union between 1889 and 1912, except Utah, enacted lifelong disfranchisement for major crimes in their first constitutions. Pennsylvania, which had rejected efforts to disfranchise convicts on several occasions in the 19th century, denied the vote to incarcerated individuals in the mid-20th century through a series of court decisions and modifications of election laws.

A graph showing the increase in the U.S. prison population from 1920 to 2014.

When Alaska and Hawaii became states in 1959 and disfranchised felons in their new constitutions, they joined 42 other states that were doing the same. Felon disfranchisement even spread to New England states, although these states limited this penalty only to the period of incarceration. New Hampshire began disfranchising incarcerated felons in 1967 and Massachusetts in 2000.

The final step was the expansion of incarceration nationally.

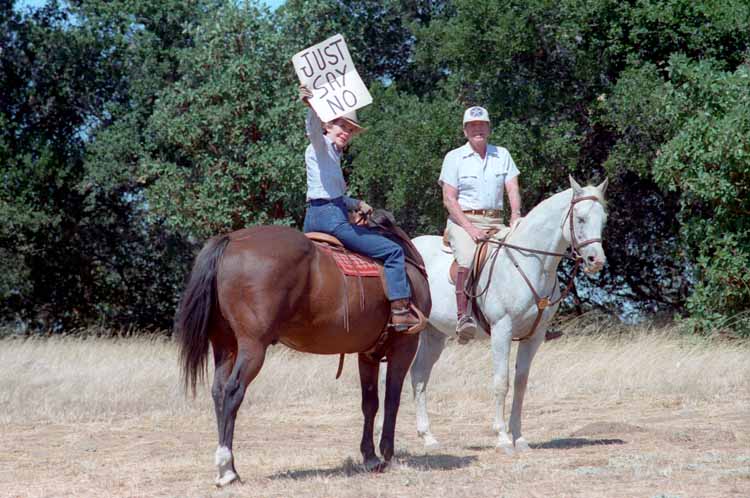

In the 1980s, politicians leveraged racial fears to spread rhetoric of crime and danger that brought about an increase in incarceration. Beginning with President Richard Nixon’s vow to be “tough on crime” and fueled by his “war on drugs,” this effort reached an apex in the Reagan administration during which the prison population doubled in an eight-year period.

The trend continued during the Clinton years. The 1994 Crime Bill rewarded states by giving federal money to expand prisons and incarceration skyrocketed.

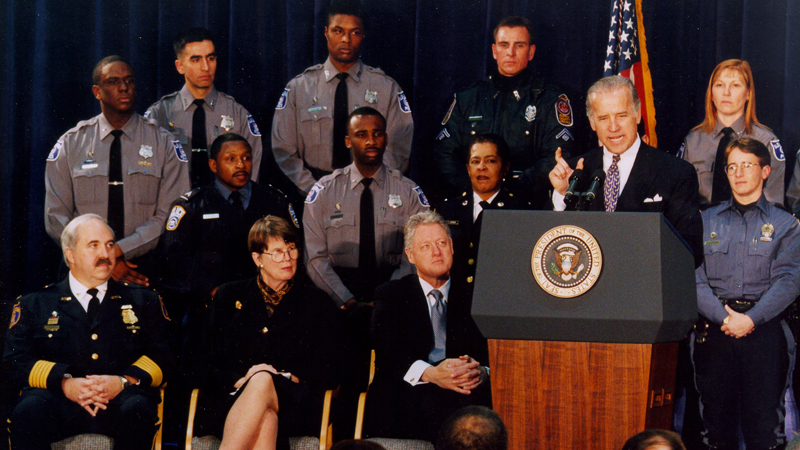

Senator and future Vice President Joe Biden speaking at the signing of the 1994 Crime Bill.

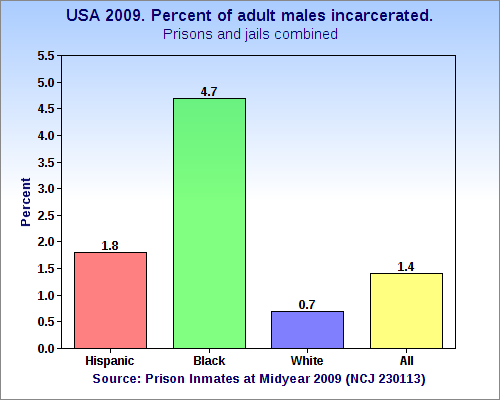

The United States has seen a 500% increase in incarceration in the past 40 years, with certain communities being affected more than others. The Sentencing Project reports that African American men are six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men, and Hispanic white men have twice the rate of incarceration of non-Hispanic white men.

As with the earlier laws that targeted black men to prevent them from voting, many drug laws specifically criminalized African Americans.

A graph depicting the racial breakdown of inmates in 2009.

One of Nixon’s top advisors later reflected on the aim of these laws to defeat the president’s political enemies: “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the [Vietnam] war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin. And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

The war on drugs disproportionately targeted African Americans and thereby disproportionately stripped them of voting rights.

Continuing Restrictions

Among western democracies, the U.S. is an exception not only in the number of individuals incarcerated, but also in limiting voting during or after incarceration. The majority of European democracies allow some or all incarcerated people to vote and extending disfranchisement post-incarceration is nearly unheard of.

That difference is a direct legacy of what happened in the 19th and 20th centuries.

A 2011 protest in New York demanding bans on felons voting be lifted.

Treating African Americans like criminals served as a convenient tool for southern whites to maintain hierarchies of political power. It is thus no surprise that laws mandating lifelong disfranchisement after a felony conviction are most common in the South today, nor is it simply a coincidence that African Americans remain disproportionately affected by these laws.

In today’s political world, because African Americans are more likely to vote for the Democratic Party, this has become a partisan issue as well. Republicans, particularly those in “purple states” where Democrats and Republicans compete to win elections by slim margins, are reluctant to implement changes that could restore the vote to a disproportionately African American, and thus Democratic, population.

In the 19th century, of course, the partisanship was reversed—Southern Democrats worked to keep African Americans from voting for the Party of Lincoln. Either way, voting constitutes one of the most basic rights of citizenship. By stripping it away from people with criminal convictions we are, in effect, denying them the right to participate in our democracy.

In the decades after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, felon disfranchisement served as the primary reason that otherwise eligible citizens were unable to vote.

Today, it is only one weapon in a growing arsenal of policies intended to attack voting rights. In recent years increasing numbers of states have required photo identification in order to vote as well as proof of citizenship in order to register to vote. States have also stepped up purges of voters who fail to vote in successive elections, charged voters who mistakenly register when they are ineligible with felony voter fraud, and more.

History shows us that unjust obstacles to voting have undermined our democracy in the past and suggests that such practices may threaten it in the future as well.

Gabriel J. Chin, "The New Civil Death: Rethinking Punishment in the Era of Mass Conviction," University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 160 (2012), 1789-1833.

Beth Colgan, "Wealth-Based Penal Disenfranchisement," Vanderbilt Law Review, 72:1, 55-189 (2019).

Alec Ewald and Brandon Rottinghaus, ed., Criminal Disenfranchisement in an International Perspective, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Richard Hasen, "Civil Right No. 1: Dr. King's Unfinished Voting Rights Revolution," University of Memphis Law Review, 49:1, 137-166.

Pippa Holloway, Felon Disfranchisement and the History of American Citizenship, Oxford University Press, 2013.

Pippa Holloway,"'They Are All She Had': Formerly Incarcerated Women and the Right to Vote." In Caging Borders and Carceral States: Incarcerations, Immigration Detentions, and Resistance, edited by Robert T. Chase. University of North Carolina Press. Justice, Power, and Politics series, 186-210.

Jeff Manza and Christopher Uggen, Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy, Oxford University Press, 2006.

Kevin Morris, "Thwarting Amendment 4," https://www.brennancenter.org/analysis/thwarting-amendment-4

The Brennan Center for Justice: https://www.brennancenter.org/issues/restoring-voting-rights

The Sentencing Project, https://www.sentencingproject.org/issues/felony-disenfranchisement/