The recent school shooting in Parkland, FL once again raised the question of the connection between mental illness and mass violence. But, if you suffer from a mental illness in the United States, you may find yourself thrown into a confusing and often contradictory system of doctors, clinics, institutions, home care, and drug regimens that is hardly a system at all. This month historian Zeb Larson traces how our response to the mentally ill has been shaped by a faith that such illness can be cured and a desire to deal with the mentally ill as cheaply as possible.

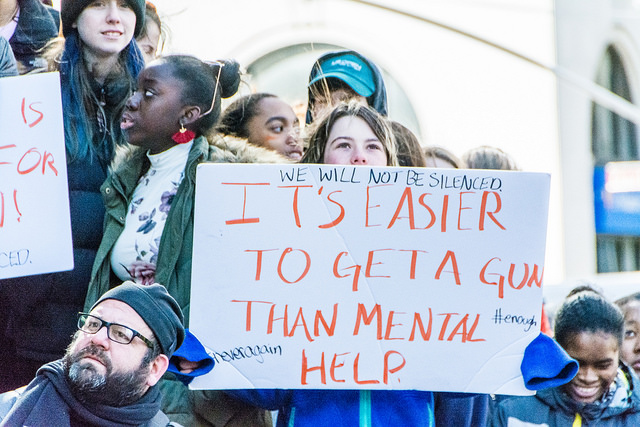

A familiar scene plays out again and again in American public life in the 21st century. In the wake of a mass shooting such as the one in Parkland, FL, commentators, pundits, and politicians all gather around to talk about the country’s broken mental health system and suggest its connection to the violence.

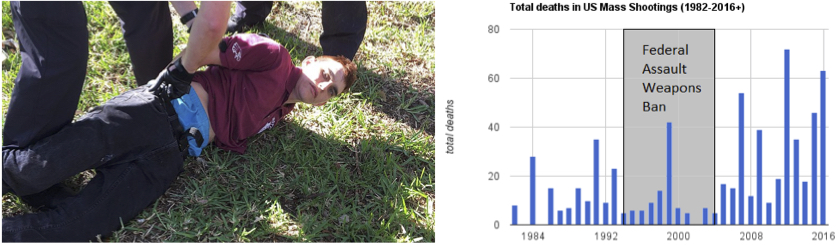

Nikolas Cruz—the suspected gunman at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, FL—being arrested (left). A graph depicting mass shooting deaths in the U.S. from 1982 to 2016 (right).

Their solutions, however, are few to none. Whether Nikolas Cruz’s mental illness was a factor in the shooting is still being investigated, but the ease with which we talk about a defective mental health system is juxtaposed with a paucity of concrete solutions.

This pattern raises the question of whether the American mental health care system is in fact broken. The metrics we have don’t paint an encouraging picture.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services reports that one in five Americans has experienced issues with mental health; and one in ten youth have suffered a major bought of depression.

A vigil for increasing mental health care at Cook County Jail in 2014 (photo credit: Sarah-Ji).

The effects of mental illness on life quality of life and health outcomes are significant. Individuals with severe mental illness such as schizophrenia, major depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder (about four percent of the population) live on average 25 years less than other Americans. As many as a third of individuals with a serious diagnosis do not receive any consistent treatment.

The mentally ill are far more likely to be the victims of violent crime rather than the perpetrators. Only 3-5% of violent crimes can be tied in some way to a person's mental illness, and people with mental illnesses are ten times more likely to be the victims of violence than the general public.

And while the relationship between mental illness and poverty is complicated, having a severe mental illness increases the likelihood of living in poverty. According to some estimates, a quarter of homeless Americans are seriously mentally ill.

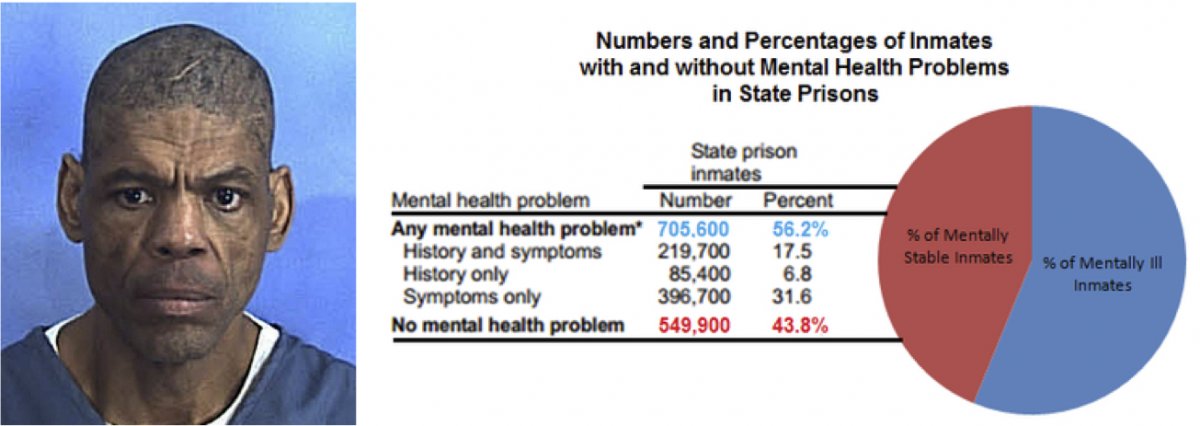

Darren Rainey, who suffered from schizophrenia, died in 2012 from burns to over ninety percent of his body after prison guards locked him in a shower for two hours with 180°F water (left). A graph and chart showing the percentage of inmates with and without mental health problems in state prisons in 2006 (right).

Most troubling, perhaps, is the criminalization of mental illness in the United States. At least a fifth of all prisoners in the United States have a mental illness of some kind, and between 25 and 40 percent of mentally ill people will be incarcerated at some point in their lives.

A study by Human Rights Watch revealed that prison guards routinely abuse mentally ill prisoners. Darren Rainey, a mentally ill prisoner at the Dade Correctional Institution in Florida, was boiled to death in a shower after being locked in it for more than two hours by prison guards.

More are sent to prison in part because fewer mental health facilities are available. The disappearance of psychiatric hospitals and asylums is part of the long-term trend toward “deinstitutionalization.” But jails and prisons have taken their place. Today, the largest mental health facilities in the United States are the Cook County Jail, the Los Angeles County Jail, and Rikers Island.

The entrance to Cook County Jail in Chicago, IL (left). The Angeles County Jail in downtown Los Angeles, CA (center). An areal view of the Rikers Island prison complex in New York City (right).

So how did we get to the point where mental illness is frequently untreated or criminalized?

Activists, advocates, and professionals like to pin the blame on Ronald Reagan, particularly his 1981 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Bill, which raised defense spending while slashing domestic programs. One of the cuts was to federal funding for state community mental health centers (CMHCs).

President Ronald Reagan outlining his tax plan in a televised address from the Oval Office in 1981.

However, attributing the present state of the system solely to Reagan would ignore the prevailing patterns in mental health care that came before him. Three impulses have long shaped the American approach to mental health treatment.

One is an optimistic belief in quick fixes for mental illness to obviate long-term care, ranging from psychotropic medications to eugenics. The second is a more pessimistic determination to make the system work as cheaply as possible, often by deferring the costs to somebody else and keeping them from public view. Last is the assumption that people with mental illnesses are undeserving of charity, either because of genetic defects or because they should be curable and thus not under long-term care.

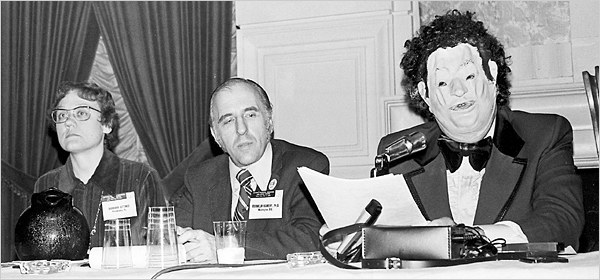

Indeed, mental health care occupies a paradoxical place in the history of social welfare in the United States, where aid is socially accepted only for the “deserving needy.” People with mental illnesses rarely fit this mold. At times, behaviors deemed socially aberrant were classified as mental illness (the American Psychiatric Association designated homosexuality a mental illness until 1973).

The Birth of the Asylum and the Hospital

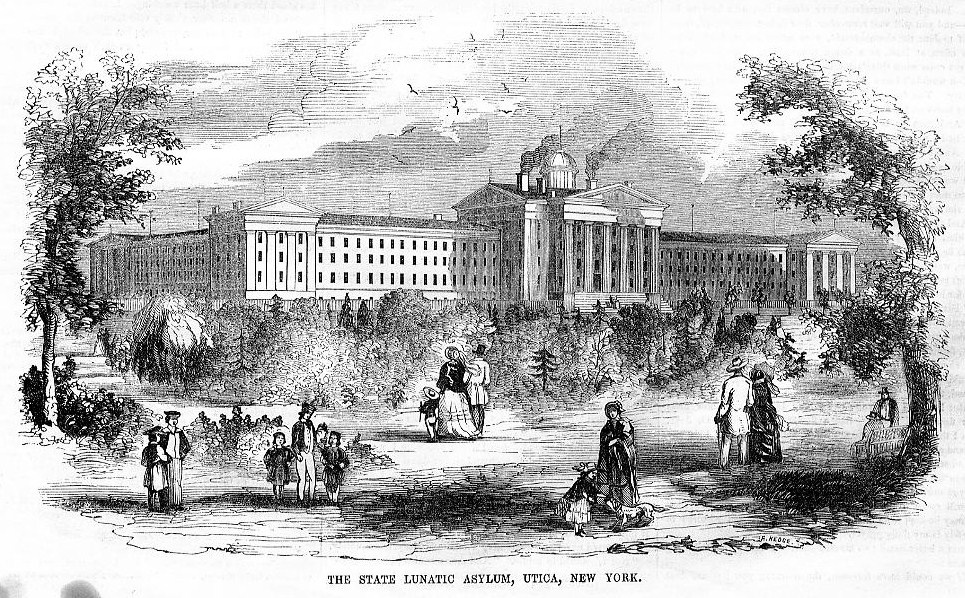

The nineteenth century saw the growth of something like an organized asylum system in the United States. Asylums themselves were nothing new. London’s Bethlem Royal Psychiatric Hospital, better known as Bedlam, was founded in 1247. In the United States however, the creation of these asylums took time, in part because their cost was deferred to state governments, which were leery of accepting the financial burden of these institutions. Consequently, local jails often housed ill individuals where no local alternative was available.

An engraving of Bethlem Royal Psychiatric Hospital in London, England around 1750.

Early in the 19th century, patients in asylums were called “acute” cases, whose symptoms had appeared suddenly and whom doctors hoped to be able to cure. Patients who were deemed “chronic” sufferers were cared for in their home communities.

The so-called chronic patients encompassed a wide range of people: those suffering from the advanced stages of neurosyphilis, people with epilepsy, dementia, Alzheimer’s disease, and even alcoholism.

The number of elderly patients in need of assistance and treatment increased in tandem with increasing lifespans during the 19th century. As county institutions grew crowded, officials transferred as many patients as they could over to new, state-run institutions in order to lower their own financial burdens.

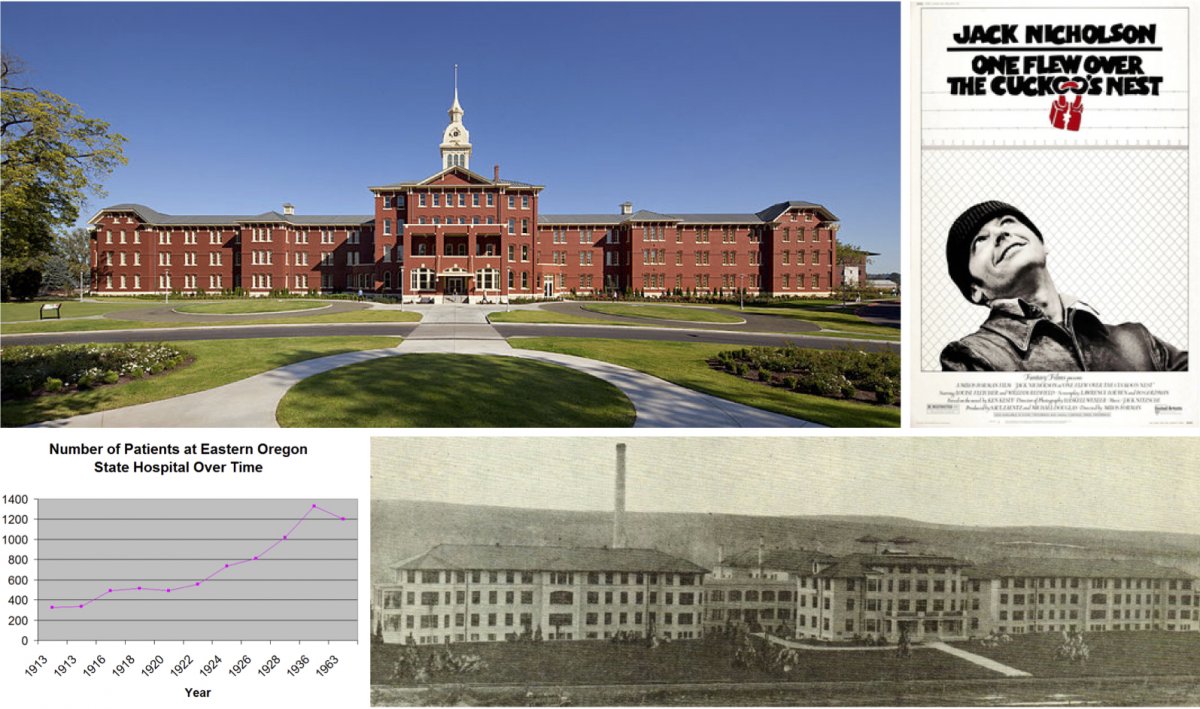

Oregon State Hospital for the Insane opened in 1883 and is one of the oldest continuously operated hospitals on the West Coast (top left). Oregon State Hospital was both the setting for the novel (1962) and the filming location (1975) of Ken Kesey's One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (top right). The patient population at Eastern Oregon State Hospital tripled in its first fifteen years (bottom left). Built to relieve the overcrowding at Oregon State Hospital, Eastern Oregon State Hospital in Pendleton itself quickly became overpopulated (bottom right).

Oregon State Hospital’s story is typical. It housed a population of 412 in 1880, expanded to nearly 1,200 by 1898, and in 1913 opened a second state hospital to house a patient population that had more than quadrupled since 1880.

Most other states confronted similar circumstances. Some built a host of smaller institutions in different counties while others concentrated their populations in a few large institutions. But the end result was the same: hospitals proliferated and grew bigger. New York’s inpatient population (which, to be sure, had outsized proportions) was 33,124 in 1915; by 1930, it was 47,775.

As the institutionalized population mushroomed, treatment of the mentally ill evolved. Doctors throughout the 19th century placed their hopes in what was they called “moral treatment,” rehabilitation through exposure to “normal” habits. In many cases, these habits included working. Most institutions were attached to farms, partly to provide food for the people living there, but also to provide “restorative” work. Others had workshops.

There is, at best, mixed evidence on whether such treatments were effective, although supporters claimed high rates of recovery for patients treated in asylums. In any event, moral treatment was only ever intended for acute cases, so it fell out of fashion under pressure from the ever-multiplying population in hospitals.

Patients performed manual tasks like shoe-making at the Willard Asylum for the Insane in New York (left). Female patients engaged in agricultural labor at a mental health facility (right).

Combined with changing patient demographics, hospitals were increasingly serving as custodial institutions. Doctors working with patients suffering from dementia or late-stage neurosyphilis could not expect those in their care to improve. The role of medical professionals shifted from therapy to caretaking.

Prevention: Eugenics as a “Cure” for Mental Illness

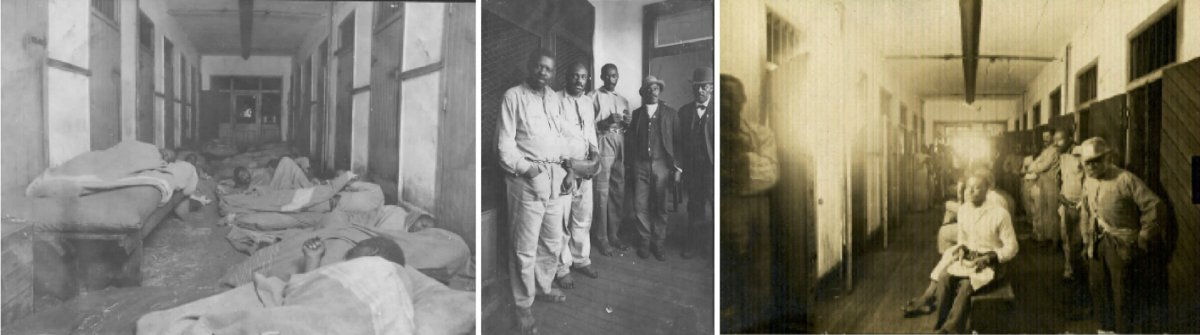

Discontented with the idea of being mere caretakers, psychiatrists began to work toward cures and preventive techniques in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The most conspicuous manifestation was the growth of eugenics and forced sterilization. These “cures” targeted specific populations, such as immigrants, people of color, the poor, unmarried mothers, and the disabled.

Southern asylums in the Jim Crow era were segregated and ones for African Americans received far less funding and accordingly suffered from chronic overcrowding, abuse, and generally deplorable conditions. An investigative commission in 1909 found Montevue Asylum in Maryland to be one of the state’s worst facilities. Patients there slept on floors with minimal bedding (left), were often shackled (center), and had little space during the day (right).

Although expressing some reservations about who was receiving eugenic treatment, many psychiatrists enthusiastically supported it. While doctors remained skeptical about the possibility of curing people with severe and persistent mental illness, preventing it through eugenics promised to solve the problem for future generations.

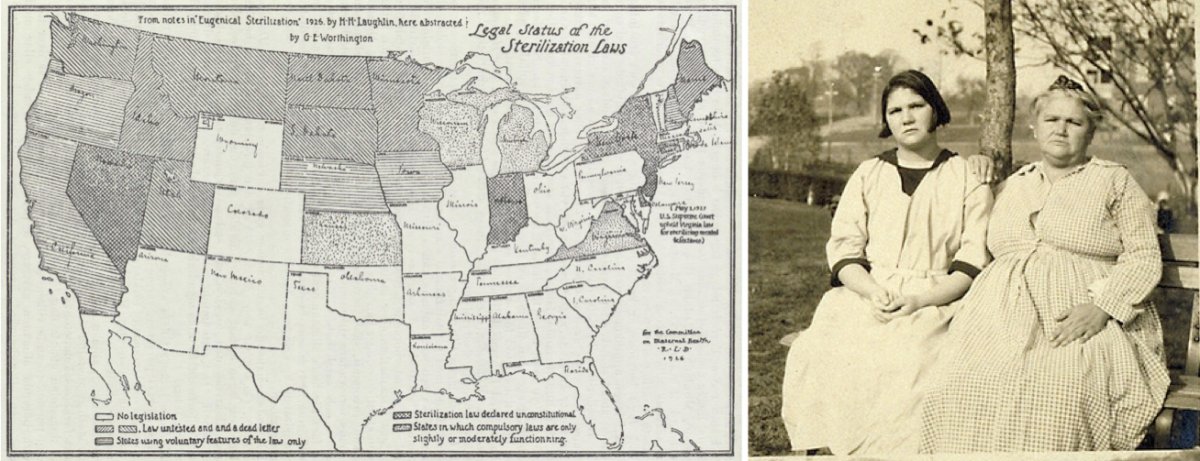

In 1896, Connecticut became the first state to prohibit marriage for epileptics, imbeciles, and the feeble-minded. In 1907, it was also first to mandate the sterilization of an individual after a board of experts recommended it. Thirty-three states ultimately adopted sterilization statutes, though certain states carried out a disproportionate number of these, with California alone accounting for a third of such operations. Ultimately, more than 65,000 mentally ill people were sterilized.

A 1929 map of states that had implemented sterilization legislation (left). Carrie Buck and her mother Emma Buck at the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded in 1924 (right). Emma had been committed after accusations of immorality, prostitution, and having syphilis. Her daughter was committed after becoming pregnant at seventeen as the result of a rape.

While we now know that these sterilizations did not prevent mental illness, courts supported the programs. In Buck v Bell, Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. argued that sterilizations did not violate people’s rights, concluding “three generations of imbeciles is enough.”

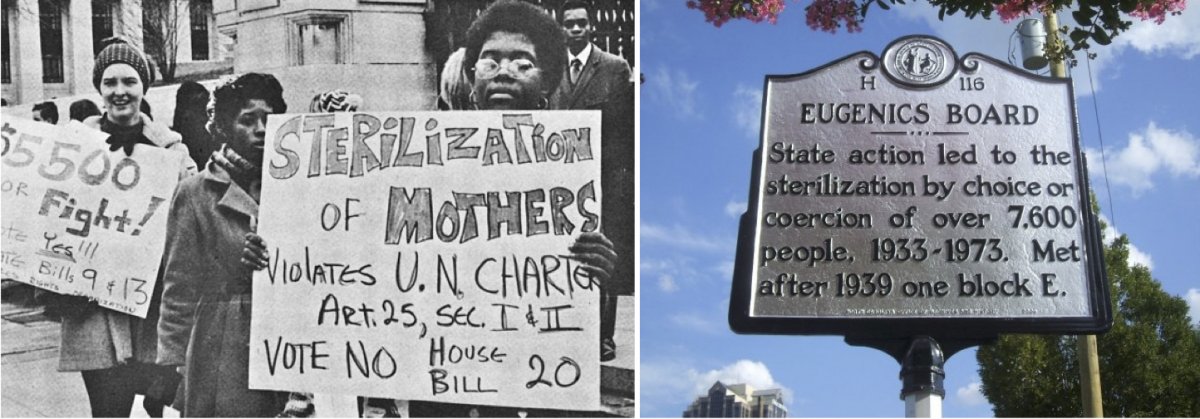

After World War II, revelations about Nazi war crimes turned many citizens against such procedures, but the procedures persisted in some places well into the late twentieth century, disproportionately affecting racial minorities. In Oregon, for example, the Board of Social Protection performed its last surgical sterilization in 1981 and disbanded two years later.

A protest against forced sterilizations in North Carolina around 1971 (left). A historical marker in Raleigh, NC regarding the 7,600 people sterilized in that state (right).

From Prevention to Treatment

Beginning in the early 20th century, some doctors wanted to try new treatments for mental illness rather than preventive measures. They focused on the body instead of lifestyle or psyche. In trying to find physiological origins for maladies, psychiatrists hoped they might treat schizophrenia, manic depression, and other illnesses.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which induces seizures in people through a series of electrical shocks, became one of the most famous such treatments and is still in limited use today. ECT remains controversial, not least because of its use on non-consenting individuals and its side effects.

Electroconvulsive therapy being administered at a Liverpool, England facility in 1957.

But clinical data indicates it can be effective in mitigating or eliminating symptoms for long periods of time. The same cannot be said for other treatments for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder that emerged in the 1920s.

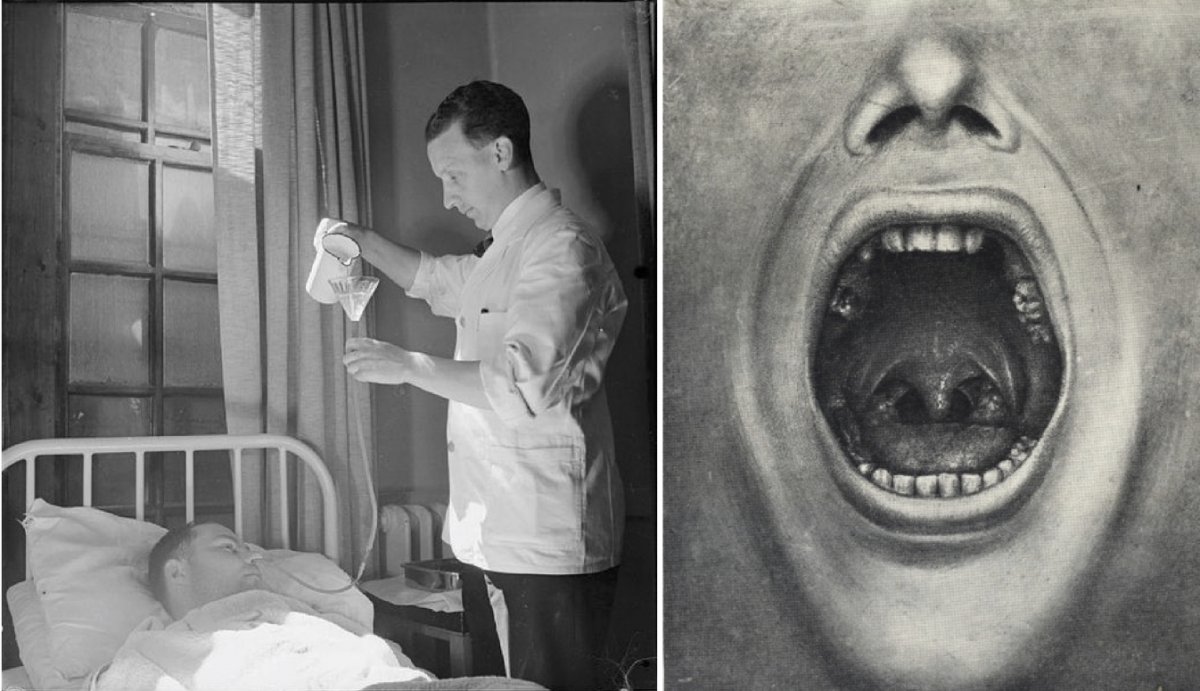

Building off of the success of malaria therapy in curing syphilis (which involved deliberately exposing patients to malaria), the Austrian therapist Manfred Sakel introduced insulin shock therapy in 1927 as a cure for schizophrenia. He injected patients with successively larger doses of insulin, often to the point of inducing a coma, then revived them with glucose and repeated the procedure. The more fortunate patients emerged from this with considerable weight gain; the less lucky with permanent brain damage or a persistent comatose state.

A nurse administering glucose to a patient receiving Insulin Shock Therapy in an Essex, England hospital in 1943 (left). An image of removed teeth from Henry Cotton's The Defective Delinquent and Insane (1921) (right).

Because the psychiatric profession was still relatively small and the bureaucracy around mental health care was primarily concentrated in hospitals, individual doctors could often experiment to see what would work.

Henry Cotton, a doctor at New Jersey State Hospital from 1907 to 1930, for example, believed that mental illness was the product of untreated infections in the body: he removed patients’ teeth, tonsils, spleens, and ovaries to try and ameliorate their symptoms. Mortality for these procedures was 30 to 45 percent.

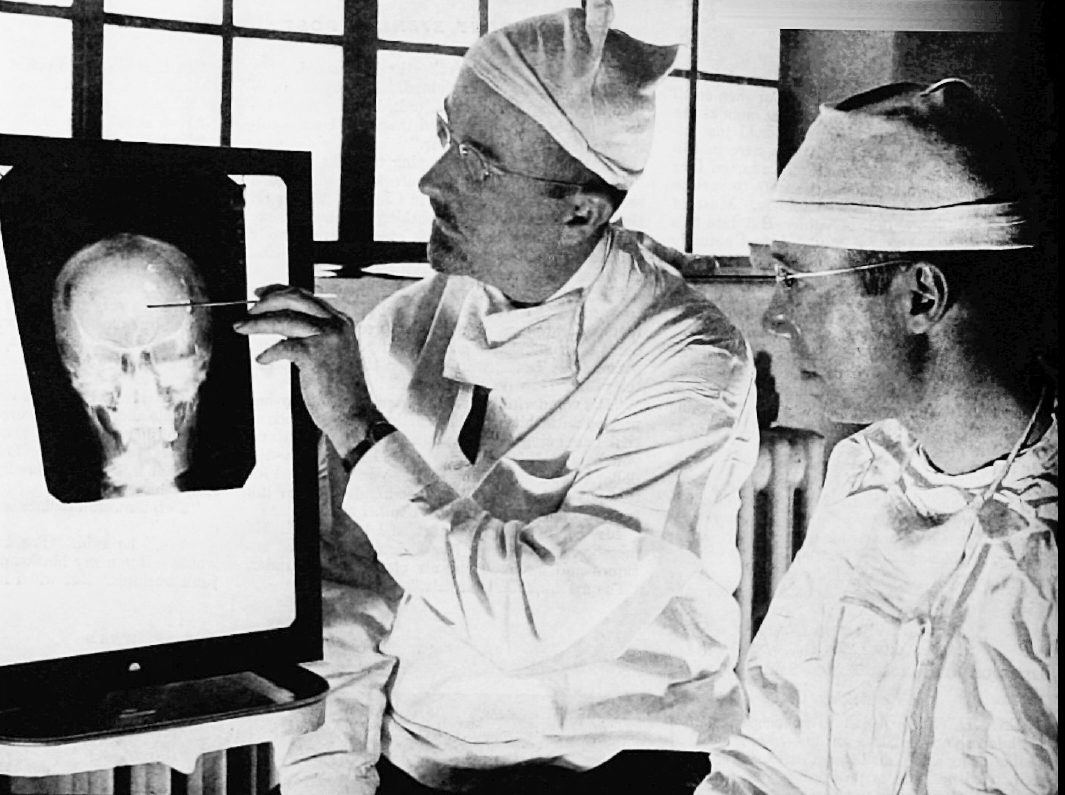

Perhaps the most extreme example of a physical treatment was lobotomization. Developed by Antonio Egas Moniz, doctors severed connections between the prefrontal cortex and the rest of the brain by either drilling through the skull or inserting an implement past a person’s eye. Around 40,000 lobotomies were performed in the United States. A few individuals recovered or showed improvement, but most showed cognitive and emotional declines, while others became incapable of caring for themselves or died.

None of these treatments arrested the alarming growth of patient populations in state institutions. In the case of insulin therapy or Dr. Cotton’s surgeries, we can see now there was no connection between the treatment and mental illness. Such treatments simply traumatized patients or inflicted lasting physical harm.

Patients vs. Budgets

The Great Depression placed further strain on these institutions and hospitals became dangerously overcrowded. States reduced appropriations for their major state hospitals while counties began sending even more people to state institutions. Spending on patient care varied widely across the nation. In 1931, New York spent $392 per capita on hospital maintenance, Massachusetts $366, Oregon $201, and Mississippi only $172.

Under these conditions, the quality of care deteriorated. For instance, Creedmoor Hospital in New York made headlines in 1943 following an outbreak of amoebic dysentery among patients. In Salem, Oregon, a patient accidentally put rat poison in the scrambled eggs in 1942, killing 47 people and sickening hundreds—a painful example of how sloppily the hospital was run.

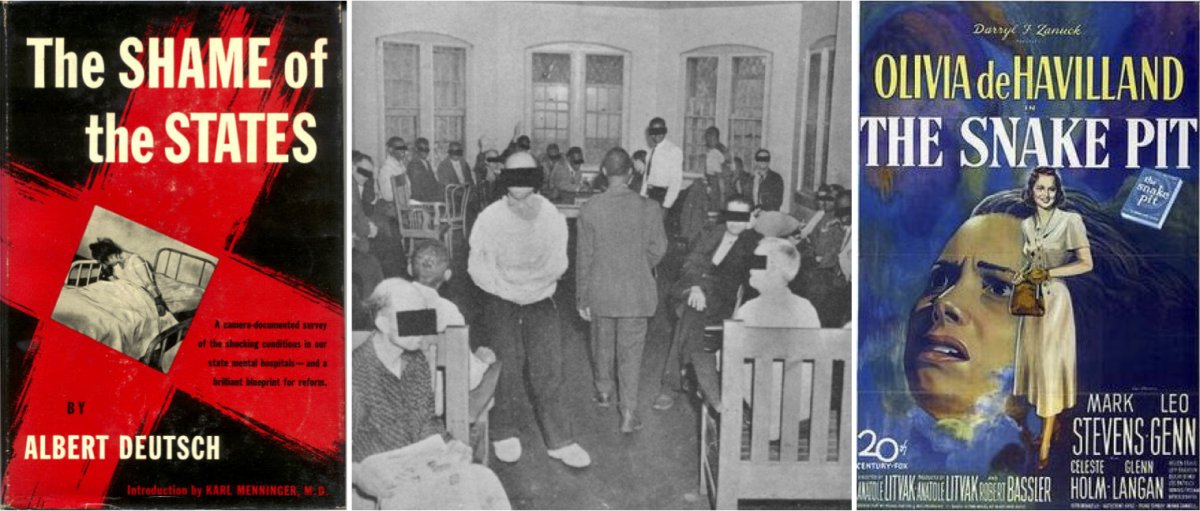

In 1948, the journalist Albert Deutsch released a book called The Shame of the States in which he cataloged various abuses he witnessed in state hospitals: overcrowding, beatings, and a near absence of rehabilitative therapy.

The movie The Snake Pit (1948) brought these conditions to life, showing the different levels of a hospital, including the “snake pit,” where patients deemed beyond recovery were abandoned in a padded cell.

Journalist Albert Deutsch published a catalogue of abuses in state hospitals in 1948 (left). One of the images in Deutsch’s The Shame of the States of an overcrowded day-room in a Manhattan asylum (center). The 1948 film The Snake Pit depicted a semi-autobiographical story of a woman in an insane asylum who could not remember how she got there (right).

Such attention, along with World War II, mobilized public support for reforms to mental health care. The sheer number of potential soldiers rejected for service on psychiatric grounds—1.75 million—shocked the public. Then, the large number of psychological casualties among men, many of whom suffered from what we now would call Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, also suggested that environmental stress could contribute to psychological problems.

Deinstitutionalization: Medicines to the Rescue?

The continual (and, many feared, financially unsupportable) growth of patient populations, the shameful conditions of the hospitals, and the postwar interest in psychiatry created a groundswell for reform.

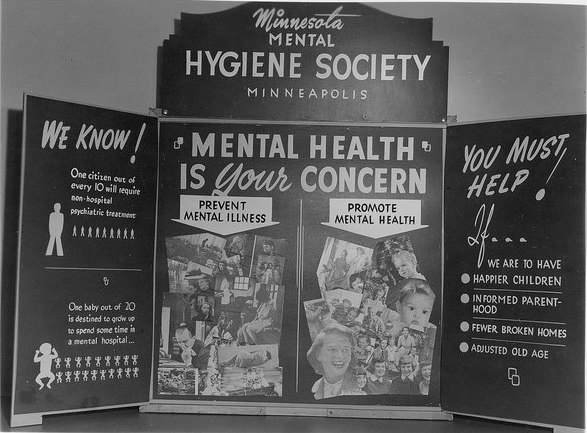

The signing of the National Mental Health Act in 1946 and the subsequent creation of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) signaled that the federal government would play a larger role in overseeing mental health and soliciting the input of psychiatrists. By the mid-1950s, NIMH studies were calling for community care rather than hospitalization.

A poster presentation at the Minneapolis Health Fair in 1944.

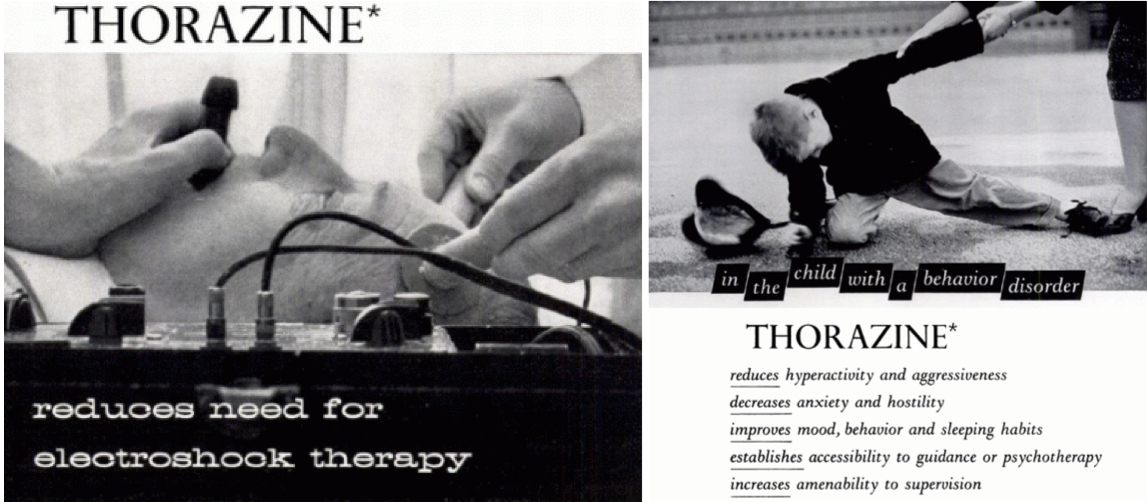

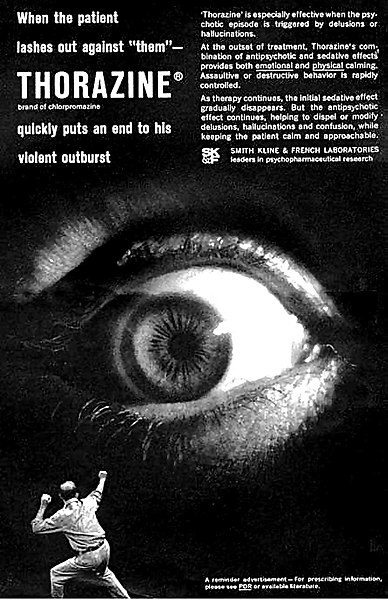

The postwar period also saw the arrival of psychotropic medications and treatments. Thorazine became the first antipsychotic, making its way to the United States in 1954, and soon proving effective at alleviating certain symptoms. Effective medications raised the possibility of moving people out of the hospitals permanently.

Generally, deinstitutionalization began around 1955 as the number of people in hospitals began to decline afterward. New York became one of the first states to reform its mental health care system, beginning with its Community Mental Health Act in 1954. This act provided funding to outpatient clinics for patients to visit for therapy or medications. Other states followed suit.

1955 and 1956 advertisements for the antipsychotic drug Thorazine in Mental Hospitals magazine.

State governments proved unwilling to pay for extensive networks of clinics, however, and counties resisted the financial responsibility. California’s mental health act asked families of those in treatment to pay, thus minimizing the tax burden. Complaints about state hospital systems frequently circled back to its cost to the states, especially as patient rosters grew longer.

At the same time, other reformers were optimistic about new, in-hospital treatments such as milieu therapy. At its core, milieu therapy tried to divide patients into small “communities” that would make decisions about collective behavior and daily life in the hospital wards. It aimed to create collaborative patient-staff relationships and teach people how to live independently.

An Expanded Role for the Federal Government

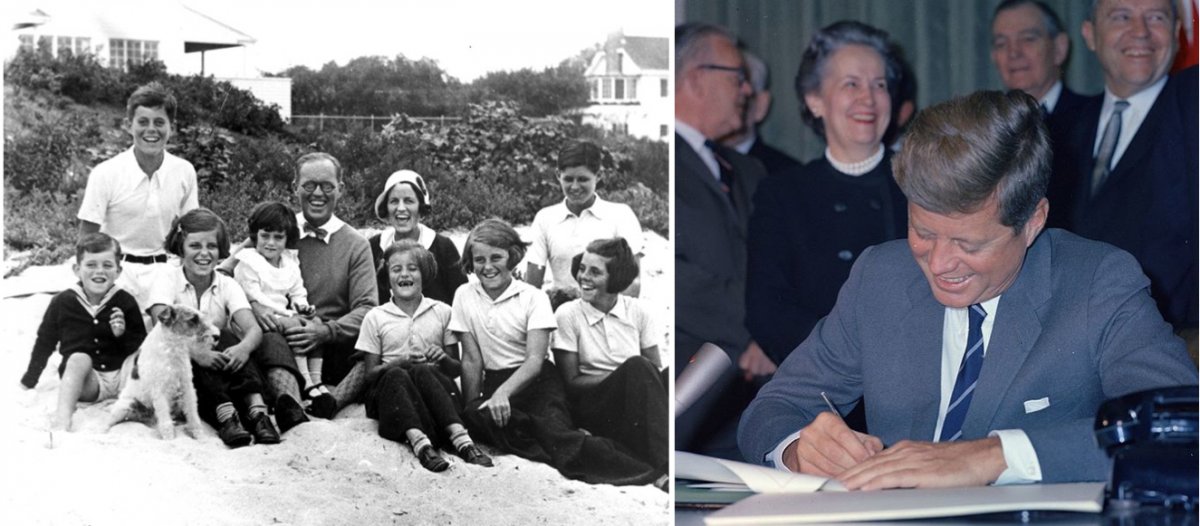

The Kennedy Administration and the Great Society helped to break the financial logjam at the state level and give politicians the monetary support to shutter their hospitals. In 1963, the president called for a new approach that would allow mentally ill individuals to live successfully in their communities.

The Kennedy Family at Hyannis Port, MA in 1931 with Rosemary Kennedy on the far right (left). President John F. Kennedy signing the Mental Retardation Facilities and Community Mental Health Center Construction Act in late October 1963 (right).

Kennedy proposed a program to “assist in the inauguration of a wholly new emphasis and approach to care for the mentally ill,” he said in a speech. “This approach relies primarily upon the new knowledge and new drugs acquired and developed in recent years which make it possible for most of the mentally ill to be successfully and quickly treated in their own communities and returned to a useful place in society.”

Kennedy’s sister Rosemary had been born with a mild intellectual disability and in her teenage years reportedly became difficult to manage. Fearing that Rosemary’s behavior might embarrass the family, Joseph Kennedy, Sr. had her lobotomized, hoping to improve her symptoms. Instead, it left her an invalid hidden away in an institution. Her father reportedly never visited her again.

Kennedy’s bill offered $150 million in grants for states to construct community mental health centers (CMHCs), with the federal government sharing between one- and two-thirds of the total cost. The centers would be required to offer inpatient services, outpatient services, partial hospitalization, 24-hour emergency services, and educational work. The bill called for 2,000 CMHCs to be built by 1980, with the goal of rendering most state hospitals obsolete. Signing the Community Mental Health Act was one of Kennedy’s last acts; he was assassinated a few days later.

The Community Mental Health Act was the brainchild of just a few psychiatrists: Robert Felix, Stanley Yolles, and Bertram Brown. They categorically opposed any significant role for state hospitals in the future, and largely bypassed the directors of state mental health programs. Felix hoped that his CMHCs would have a preventive effect on mental illness. Certainly, Kennedy seemed optimistic about the prospects of medications, which he said could successfully and quickly treat people to return them to a “useful place in society.”

Felix’s belief that the CMHCs would prevent mental illness was unfounded; there is little evidence that they had any positive effect. Underfunded from the beginning, by 1980, only 754 of the promised centers were in operation. But the CMHC program did have the effect of undermining the role of hospitals in mental health care.

The states, in turn, had an ambivalent relationship with the CMHCs, in part because the funding structure demanded that states pay increasingly more for the centers. Because of that, many CMHCs sent patients requiring significant care back to the hospitals. Absent a suitable number of centers, states fell back on developing aftercare and clinics, which were spotty at best.

Originally known as the Great Asylum for the Insane, Agnews State Hospital in Santa Clara, CA opened in 1885 and closed in 1998 (left). Built after World War II, the Demented Men’s Building at Agnews State Hospital (right) was an attempt to move toward preparing patients to leave the hospital.

Other federal programs had the effect of further emptying the state institutions. Medicare provided funds for the elderly to be treated in nursing homes rather than hospitals. In 1972, Social Security was modified so that payments could be made to individuals not living in a hospital, to encourage people to live independently. Medicaid also was designed to encourage states to move people out of hospitals and into smaller facilities. States could only be reimbursed for expenses if individuals were living in a facility with 16 or fewer beds.

States Get Out of the Business of Mental Health, or Try To

Under the new federal strictures, states had incentives to close their asylums. California, under Governor Ronald Reagan, became a leader in deinstitutionalization and set an example for other states.

Yet California’s deinstitutionalization also reveals the dual impulses that drove politicians. Nick Petris, a state legislator, worked to limit the number of involuntary commitments by passing laws that restricted how people could be sent to a hospital. Once those hospitals were closed, Petris hoped the funds would follow the patients. Instead, in the landmark Lanterman-Petris-Short Act that Petris authored, Governor Reagan diverted the funds that were supposed to pay for patient care at the county level into the state’s general fund.

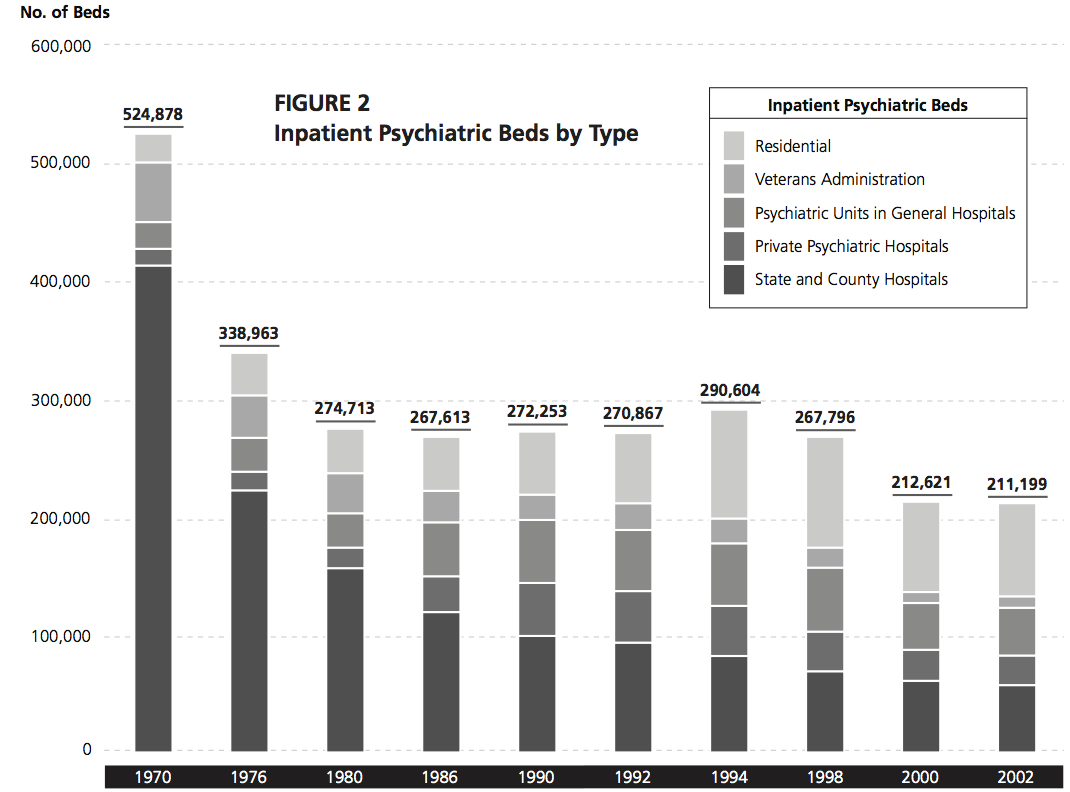

A graph depicting inpatient psychiatric beds by type from 1970 to 2002.

Even states that had historically been sympathetic to funding mental health care followed the pattern. New York counties resisted opening centers because of the funding formula the state had instituted. In Massachusetts in the mid-1970s, under Michael Dukakis, hospital closures accelerated partly out of the need to slash budget expenditures. Once budgets were slashed, many hospitals saw their quality of care decline further, leading to more demands that they be emptied and closed.

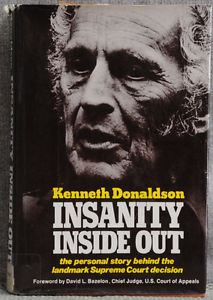

Decisions in both the state and federal courts also changed how commitment worked, further shrinking state hospitals. The culminating Supreme Court decision, O’Connor v. Donaldson (1975), held that people not deemed to be a threat to themselves could not be hospitalized against their will.

After the 1975 decision, hospitals became (as they remain today) forensic institutions for the most part, housing criminal offenders or individuals awaiting trial. As a result, from 1970 to 2016, the number of inpatient psychiatric beds in the United States declined from 413,000 to 37,679.

Deinstitutionalization: What Happened to the People?

Many individuals’ quality of life improved after leaving the hospitals—a process that accelerated from the 1950s. Medications significantly enhanced their ability to manage their symptoms.

Once people exited hospitals, their destinations varied. Reformers hoped that they would go home to families, but in many cases, people had no family connections. Without family to support them, and often having never lived independently, people with mental illness often turned to the federal government for support.

The number of halfway homes exploded. Often these group homes were opened by ex-hospital staff. They tended to cluster in low-rent areas of major cities, partly because that was where the operators could afford to run them, and because neighborhood associations were generally unwilling to accept group homes in safer, more affluent neighborhoods.

The quality of these homes could vary dramatically: most states paid the operators of such homes by the head, which gave them incentives to maximize profits. Horror stories became distressingly common from the 1970s onward. A house fire in Worcester, MA, killed seven people in a group home, while nine people in Mississippi were found living in a 10- by 10-foot shed with no running water and only two mattresses. The worst of these houses came to resemble the hospital wards people had left, with drab environments and limited contact outside the house.

The promise of medications to “cure” mental illness has also faltered. Medications have proven variable in their efficacy from person to person. They might be useful in controlling one set of symptoms while failing to address another.

They also frequently involve a number of side effects, the most widely known of which is the “Thorazine Shuffle” (a combination of the tranquilizing effect of drugs with restless legs, making consumers walk with a shuffling gait) but others include severe weight gain, facial tics, and muscle spasms.

Medications must be taken consistently to remain effective. This helped to reinforce the so-called “revolving door” of mental health in which a person discontinues a medication, decompensates psychiatrically, is arrested or hospitalized, recovers, and repeats.

Policy makers never considered these complications of drug-based solutions. Doctors were often circumspect about the effectiveness of medications, but professional medical input into federal government programs was limited.

The era of deinstitutionalization reached its denouement with Reagan’s 1981 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act. It repealed federal funding for CMHCs, transformed other federal aid to the states into block grants, cut the dollar outlays by as much as 30 percent, and left the states with broad discretion over how to spend the money. By the mid-1990s, hospitals had mostly shrunk to their present size.

Mental Health Today

It would be a mistake to paint deinstitutionalization as a through-and-through failure.

The hospitals that existed in the 1940s were often abusive, and many people today can live their lives in a way they might only have dreamt of a century ago. Hospitalization was not the best option for people with mild symptoms that could be managed through medications.

Yet many people were left behind as well, either on the street or in jails and prisons.

What is striking about the legacy of deinstitutionalization is how much of it was motivated by financial opportunism on the part of the states. Over the course of the 20th century, states’ elderly patients could have their treatment funded by Medicaid, hospitals could be shrunk and staff ratios could be improved without having to actually spend more money, clinics would be cheaper to run than hospitals, and medications would maybe even obviate the need for any treatment at all.

This focus on reducing funding outlays helps to explain the limitations of this brand of reform: it was supposed to be cost-effective. Those individuals who required more support once they left the hospitals found themselves abandoned.

The creation of a large, indigent class of people with mental illnesses was not inevitable from a policy perspective. Studies from the United States, Germany, and Switzerland, among other countries, have confirmed that even people who have been institutionalized most of their lives and who have experienced severe mental illness for years on end can live independently if they have certain supports available: housing, aftercare, support networks, and jobs.

However, in the United States, those supports frequently have not existed, or in certain cases, have been eroded or ended once people returned to the community. Psychiatrists such as Robert Felix underestimated the extent to which they would be necessary, and politicians at the state and federal level were unwilling to spend the money.

As the mental health system again reemerges in public and policy discussions in the wake of another mass shooting, the question remains: Is there a link between closing the hospitals and mass shootings? In all likelihood, no. Americans do not suffer from higher rates of mental illness than other people in the world.

While not all agree, the general consensus among psychiatrists is that there is no meaningful link between mental illness and the number of mass shootings. Representing this majority scientific view, epidemiologist Matthew Miller argues that the number of mass shootings in the United States has far more to do with the availability of guns. In contrast, some psychiatrists such as E. Fuller Torrey maintain that there are certain links between untreated mental illness and violence (although Torrey’s conclusions are controversial and are challenged by other experts).

President Trump has recently suggested that the United States needs more hospitals and asylums to prevent future shootings. Whether this proposal is serious is up for debate. Current commitment laws would make it difficult to hold people against their will en masse.

To respond in this manner would simply reframe mental illness as a problem of violence, not of mistreatment and maltreatment of Americans with mental illness. Such a program would be unlikely to fix a broken system.

As for the state of Florida, legislators are trying to pass additional appropriations for mental health care. The long history of American approaches to mental illness should leave us doubtful that the funding would remain for long.

Read more from Origins on mental health, medicine, and guns: Health Policy Precedents, Fluoride and Public Health, Gun Control in Canada and the U.S., Free Market Health Care, Second Amendment Goes to Court.

Listen more from Origins on public health and policing: Policing in America, Affordable Care Act.

Alex Beam, Gracefully Insane: The Rise and Fall of America’s Premier Mental Hospital (New York: Public Affairs, 2003).

Michel Foucault, Madness and Civilization: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason (New York: Vintage Books, 1988).

Gerald Grob, The Mad Among Us: A History of the Care of America’s Mentally Ill (New York: The Free Press, 1994).

Jack el-Hai. The Lobotomist: A Maverick Medical Genius and His Tragic Quest to Rid the World of Mental Illness (Hoboken: Wiley, 2007).

Ken Kesey, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (New York: Signet, 1963).

Jonathan Metzl, The Protest Psychosis: How Schizophrenia Became a Black Disease (Boston: Beacon Press, 2009).

Darby Penney, The Lives They Left Behind: Suitcases from a State Hospital Attic (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2008).

Edward Shorter. A History of Psychiatry: From the Era of the Asylum to the Age of Prozac (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1997).

E. Fuller Torrey. American Psychosis: How the Federal Government Destroyed the Mental Illness Treatment System (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Robert Whitaker. Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America (New York: Broadway Paperbacks, 2010).