It is a time-worn cliche that baseball is “America's game.” As long ago as 1889 poet Walt Whitman called baseball “our game” and enthused that it “has the snap, go, fling, of the American atmosphere.” In fact, baseball has long been an international game and nowhere has it been played with more passion than in the Dominican Republic. This month, Andrew Mitchel reviews the relationship between the United States, the Dominican Republic, and the game that both love.

Over the past century, baseball has become a truly global game.

The sport debuted at the Olympics in 1904, and professional play in Japan began in the 1920s. Nowadays, the Miami Marlins push their players and coaches to speak both English and Spanish. And in our sports-starved COVID-19 era, the first baseball league to return to television in the United States was the KBO from South Korea.

But nowhere has baseball become more significant than in the Dominican Republic. In fact, baseball has been at the center of the relationship between the United States and the Caribbean island nation for decades. The game has created a culture of entanglement and co-dependence with profound social consequences for players and fans alike.

Play Ball! (… In the Dominican Republic)

Baseball was introduced to the Dominican Republic by Cuban sugar moguls as early as the 1870s. Teams quickly sprung up in urban centers, especially the capital city of Santo Domingo. But the broader public appeal grew because of games played on those sugar plantations, especially when work was light during the tiempo muerto (dead time)in the growing cycle. Over time, these groups morphed into company teams sponsored most often by rum, sugar, and fruit enterprises.

Many who played the sport on these plantations were seasonal workers from the West Indies, where cricket had been much more popular. These communities soon adjusted to baseball once they settled in sugar towns like La Romana and San Pedro de Macoris. These migrants eventually became the ancestral kin of many of the most famous Dominican-born ball players from these towns. San Pedro de Macoris, for example, is known as the “cradle of shortstops.”

Baseball grew in the Dominican Republic during the same period as U.S. expansion of political and economic control in the Caribbean basin and around the world. The 1898 Spanish-American War ousted colonial Spain from the Americas. This enabled the United States to consolidate its dominance over affairs in Latin America and beyond.

The Roosevelt Corollary (1904) to the Monroe Doctrine stipulated that the doctrine “may force the United States, however reluctantly, in flagrant cases of such wrongdoing or impotence, to the exercise of an international police power.” This policy was first executed to secure Panamanian independence from Colombia and building the Panama Canal. The United States sought to open the world to its influence, even if by force.

In 1916, 600 U.S. Marines landed in the Dominican Republic to protect the legitimacy of the elected President Juan Jiménez and ostensibly to make sure the island did not relapse into European colonial hands. These Marines stayed until 1924, long after the First World War was over.

Baseball served as common ground between the occupied and occupying during this period of intervention, and it offered the opportunity for the Dominicans to beat the Americans. Local teams would play, and often beat, groups of Marines.

This period sparked a national craze for baseball. Once the last U.S. troops left the Dominican Republic, it ushered in a baseball era nostalgically remembered today as beísbol romántico.

Even so, the period was not without frictions. Dominican player ‘Fellito’ Guerra impressed American observers enough that he was offered a contract with an American team. He turned down the offer to protest of the U.S. invasion of his nation.

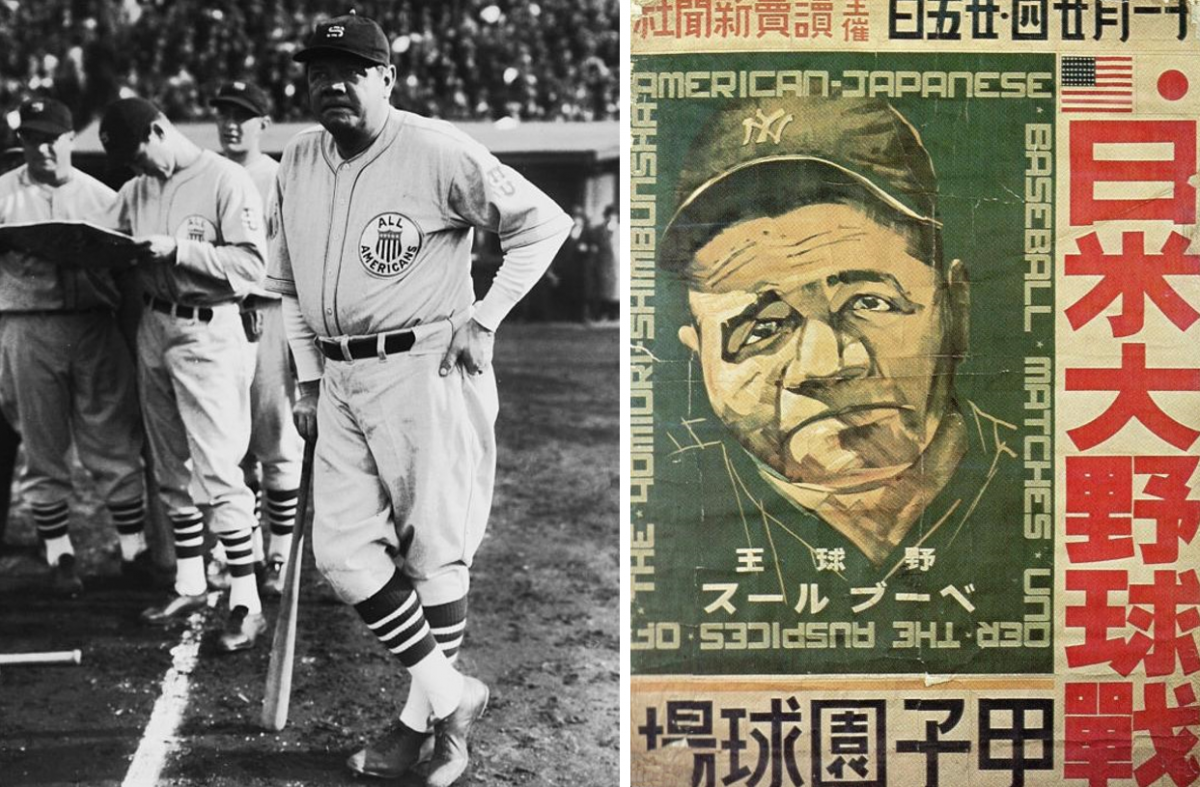

Dominicans were not alone in their embrace of baseball. The United States deployed baseball as part of a larger effort to promote American interests around the globe through what has been called “baseball diplomacy.” Early ball players often went on goodwill tours abroad. A group of Major Leaguers including Babe Ruth, for example, visited countries like Japan in 1934 not just to spread the game, but also U.S. influence.

Baseball diplomacy in action. Babe Ruth playing for the 1934 All-American tour in Japan (left). Poster for the 1934 Japan Tour with American All-Stars, featuring Babe Ruth (right).

The nations that fell under U.S. political and/or economic hegemony in the 20th century—the Spanish Caribbean, Central America, Mexico, Venezuela, Japan, and South Korea—remain the nations where baseball is most popular today.

Baseball and Nationalism, Dominican Style

For elites throughout the Spanish Caribbean, the United States represented all the “modern” principles of the era: democratic governance, technological advancement, and capitalist power.

Many of those elites did business in the United States, sent their sons to college there, and imported many cultural influences back from the North. Baseball offered just one way for elites in the Spanish Caribbean to mimic U.S. citizens and to slough off the vestiges of Spanish rule. Bullfighting was out, baseball was in.

For non-elites, baseball developed as a cultural touchstone and part of daily life. During the beísbol romántico period, a league structure was slowly developed. Since each town has its own team, and corporate entities were already the purveyors of uniforms, gloves, and other equipment, it was only a matter of time before this became a money-making operation.

Though baseball was first used to promote cohesion and appease worker desire for leisure, quickly this changeover allowed companies the chance to win games and get their name out to the public as an advertisement and allowed talented ball players to earn a salary.

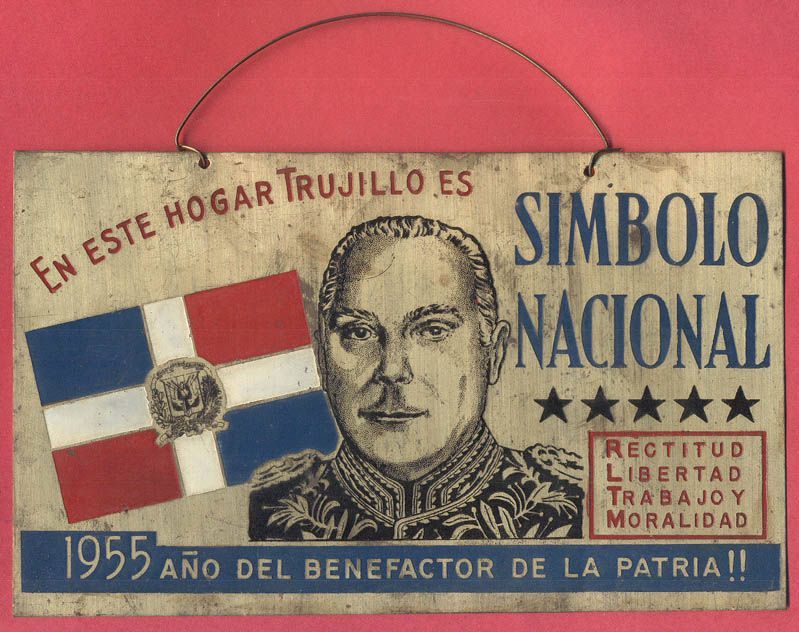

By 1937, two things were true in the Dominican Republic: baseball was the national pastime and Rafael Trujillo was entrenched as leader. Trujillo had been trained by U.S. forces during the invasion and had risen through the ranks from the constabulary to head of the military in 1928. He became president in 1931. Trujillo himself was not a baseball fan, but he and his son Ramfis saw it as a useful tool to unify the population.

The capital of Santo Domingo was renamed Ciudad Trujillo, and this was the site of the Dragones de Ciudad Trujillo super team experiment. The team was created as a publicity stunt to dominate the Dominican baseball league and showcase Trujillo’s total power over the nation.

Since the team was run by the Trujillo government, it attempted to recruit players from other nations as well. Three future Baseball Hall of Famers from the Negro League’s Pittsburgh Crawfords played in the Dominican Republic: pitcher Satchel Paige, catcher Cool Papa Bell and outfielder Josh Gibson. All three were barred from playing in the still-segregated American major leagues.

They came to the Dominican Republic on the promise of higher wages. Bold as this move might have been, it bankrupted the league, which could not afford the exorbitant salaries offered to the best players available.

Though they escaped American segregation by coming to the Dominican Republic, those three stars found that Dominican race relations were fraught in their own way. In October 1937 Trujillo ordered the massacre of 15,000 Black Dominican citizens who allegedly were of Haitian descent. As in other nations across Latin America, including Argentina and El Salvador, this mass murder was carried out in the name of desired pureza de sangre, or purity of blood.

The Dominican Republic Goes to the Majors; The Majors Come to the Dominican Republic

Trujillo was assassinated in May 1961 after ruling the Dominican Republic for 30 years. By that point, the country had ceased to be a full-time destination for players from across the Caribbean.

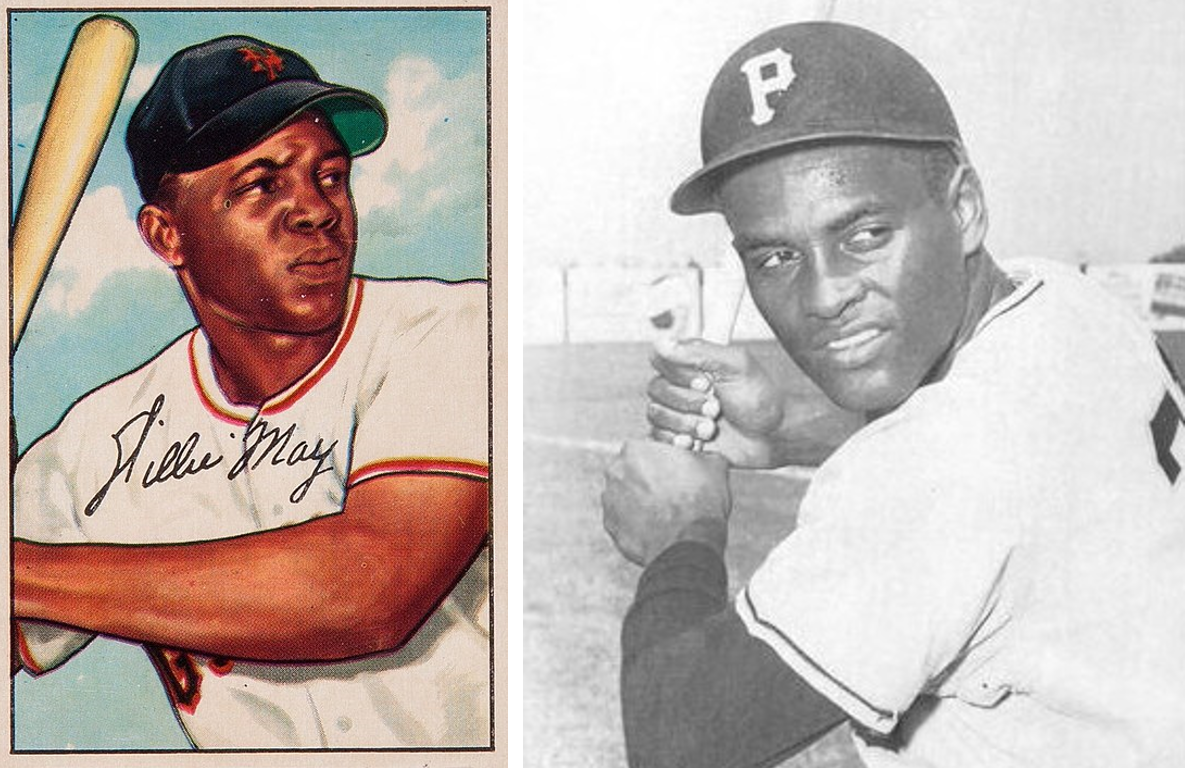

Willie Mays’ 1952 Bowman Gum trading card (left). Baseball Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente played for the Santurce Cangrejeros team from 1952 to 1954 (right).

Puerto Rico and Mexico moved in to obtain talented players to dazzle fans at mid-century. The Mexican league used high salaries, provided by wealthy team backers, to lure top talent. The Puerto Rican leagues developed young talent. During the winter season of 1952, for example, fans of Puerto Rico’s Santurce Cangrejeros team could watch American Willie Mays and native son Roberto Clemente play together.

The Dominican Republic retained its winter league, Liga de Béisbol Profesional de la República Dominicana known by its Spanish acronym LIDOM, in which many Latin American major league players appear each offseason. The passion and excitement of this league is unrivaled despite its short season. Fans fill these stadiums and create a party-like environment in support of their local teams. Baseball remains this critical cultural touchstone even as much of its best talent has left the island nation to play in the United States.

But undoubtedly the biggest story in Caribbean baseball in the mid-20th century was the serious arrival of Major League Baseball (MLB). After World War II, American teams started scouting players in the Dominican Republic. Before the 1950s, the only Latin American players to appear in MLB were a few Cuban pitchers who passed as white. When Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in American baseball in 1947, he opened the door for not just Black players, but Latinx ones as well.

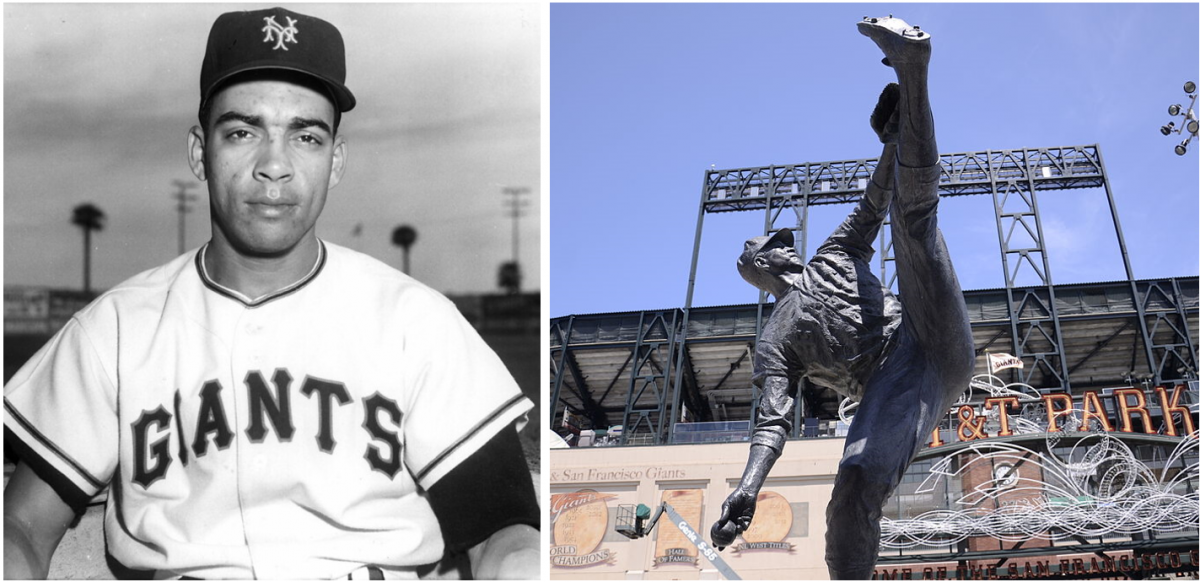

Ozzie Virgil became the first Dominican-born player in the majors, first appearing for the New York Giants in 1956, though he had spent much of his childhood in the growing Latinx community in New York City.

Ozzie Virgil with the New York Giants in the 1950s (left). Juan Marichal’s statue outside the San Francisco Giants stadium (right).

Among other pioneering recruits was pitcher Juan Marichal, widely considered the best Latin American pitcher in MLB history. Giants scouts discovered him in 1957 playing for another Trujillo-run team, the air force team called Aviación. Marichal did not actually have to serve in the military; he served by playing baseball. He debuted in the majors in 1960.

The Dominican Republic, and the Caribbean more broadly, was now recognized as a producer of talent by some teams: The Giants had the first serious scouting system; by the 1970s so did the Pittsburgh Pirates, the Toronto Blue Jays, and the Los Angeles Dodgers.

One consequence of free agency in baseball, which arrived in 1972 after a court case brought by African American player Curt Flood made it all the way to the Supreme Court, was the advent of young—and thus cheaper—players, many of whom came from overseas. MLB teams spent more on scouting young talent, and those scouts sent Latin players to the U.S. for training in the Minor Leagues.

Creating a Pipeline

For Dominican men, playing baseball in the United States now represented not just a job, but also an opportunity to escape the poverty and violence of their homeland. They arrived alongside other Dominican political and economic refugees. While these migrants moved to cities like New York, Boston, and Miami, ball players began to establish social networks of their own as a collection of Latinx players aiming for major league stardom. Both groups began to send remittances back to the island and form a hybridized Dominican American culture.

A 1978 baseball game between the Dodgers and the Reds.

That aspiration became more formalized in 1977. In that year, “super-scout” Epy Guerrero, himself Dominican, took ten Dominican players he had signed and housed them together so they could hone their skills. The Dodgers and Pirates, already involved in scouting in the Caribbean, quicky copied this model.

The idea of a closed baseball academy was born, and they were also established to cut down on the culture shock faced by players moving to the United States without knowledge of English or American culture. Today all thirty MLB clubs have a presence on the island in the form of these academies.

Players signed by these teams at just sixteen years old often support their whole family or even an entire village. Contracting Dominican talent has grown dramatically, and greed and conflict have emerged with it. Players were even hidden away by one team so other teams could not see them. In a sense, baseball players have become another product exported to the United States.

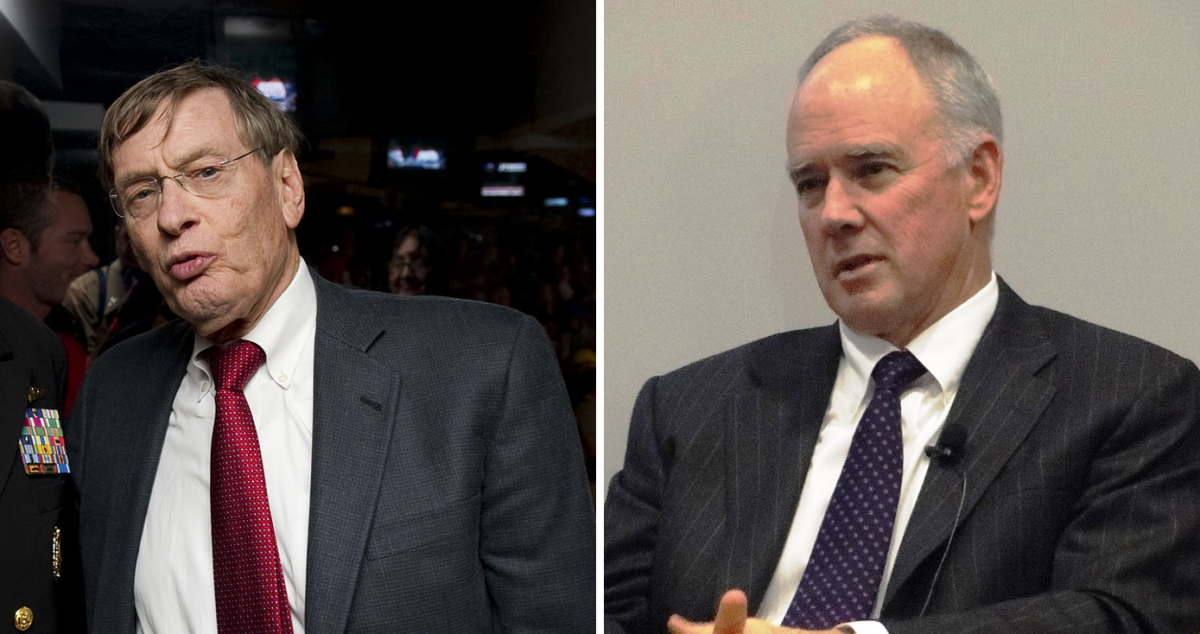

MLB has identified two key problems in the open market for players it wants to root out: false reporting of players’ ages and use of performance-enhancing drugs. It exerted its control of the Dominican baseball marketplace in 2010 when Commissioner Bud Selig sent ex-Marine Sandy Alderson to “fix the situation” and solve these problems.

Bud Selig pictured in 2010 (left). Sandy Alderson pictured in 2011 (right).

Alderson established a registry of fingerprinted athletes to protect against the falsification of ages, as well as a more rigorous drug testing program for international signees. MLB felt the buscón, who served as half-trainer half-agent and who represented many of the best players, were taking advantage of the system. They were often scapegoated as the main source of issues.

The Dominicans were cajoled into agreeing to these demands. If they didn’t, MLB threatened to move the academies off the island or to establish an international draft. Acceding to these changes, therefore, was better than losing their system altogether.

The Future of the “National Pastime” is International

Today, major league players from the Dominican Republic, Venezuela, Mexico, Cuba, and a few other nations account for between 25 and 29 percent of MLB rosters. The academies in the Dominican Republic, as places to concentrate talent to scout, have helped make Dominicans the largest single group of foreign nationals in MLB, further boosting the sport’s popularity there. These numbers do not even include the minor leagues, as many of the players riding the buses and striving for their chance in MLB are also from Latin America.

Cultural frictions between the way Dominicans play baseball and the way many Anglo-Americans think it should be played remain.

Fernando Tatis Jr., the next Latin superstar (left). Jose Bautista’s famous bat flip from the 2015 ALDS (right).

They are most visible in the debate over the bat flip—when a player theatrically throws his bat in celebration of a big hit. This kind of jubilation contrasts with the American style of play, which is more reserved and focuses on more mundane displays of hustle and grit. Even this may be fading, however, as younger and more open-minded fans enjoy the show, and MLB realizes it must promote its young Latin stars, like Fernando Tatis Jr., to remain relevant to those younger audiences.

Still, with the sheer number of Latinx players in the MLB has come a wider acceptance of their presence in American baseball by fellow players. Former MLB outfielder Nate McClouth, for example, speaks impeccable Dominican Spanish. He credits his time in the minor leagues with Dominican and Venezuelan teammates for his mastery of a second language.

Over the decades, baseball has offered Dominican players a chance at stardom and the money that comes with it. Latin representation has increased on local and national television as ballplayers humanize these non-white celebrities. They have become ambassadors for all Latinx immigrants.

Red Sox shortstop Xander Bogaerts practicing at Fenway Park, 2016.

Current shortstop for the Boston Red Sox Xander Bogaerts is quoted in TIME talking about the diversity of baseball, saying the sport “is a true melting pot. It’s like this in practically every clubhouse you go into.”

Elias, Robert. The Empire Strikes Out: How Baseball Sold U.S. Foreign Policy and Promoted the American Way Abroad. New York: The New Press, 2010.

Gregory, Steven. The Devil Behind the Mirror: Globalization and Politics in the Dominican Republic. Berkeley: University of California. 2007.

Klein, Alan. Dominican Baseball: New Pride, Old Prejudice. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2014.

Klein, Alan. Sugarball: The American Game, the Dominican Dream. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993.

McKenna, Thomas. “The Path to the Sugar Mill or the Path to Millions: MLB Baseball Academies’ Effect on the Dominican Republic.” Annual Baseball Research Journal 46, No. 1. (Spring 2017): 95-100. https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-path-to-the-sugar-mill-or-the-path-to-millions-mlb-baseball-academies-effect-on-the-dominican-republic/

Perez Jr., Louis A. “Between Baseball and Bullfighting: The Quest for Nationality in Cuba, 1868-1898.” The Journal of American History 81, No. 2 (1994): 493-517. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2081169.

Regalado, Samuel O. Viva Baseball! Latin Major Leaguers and Their Special Hunger. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

Ruck, Rob. The Tropic of Baseball: Baseball in the Dominican Republic. Lincoln: Bison Books, University of Nebraska Press, 1998.