On February 2, 1894, 125 years ago, a federal decree was entered in Pennsylvania that would alter the American diet. The case was the United States v. E.C. Knight, et.al. While a court case might seem of little significance to what we eat, this case effectively created the legal context for sugar to become ubiquitous.

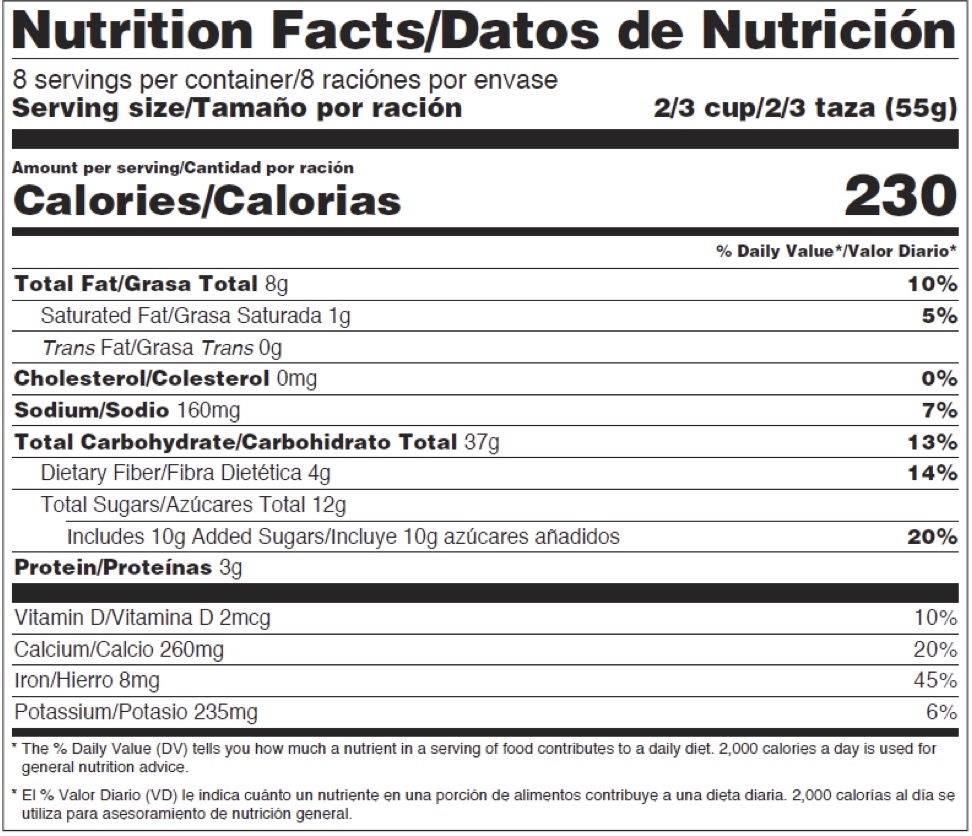

Look at any U.S. food label today and you will find that one of the top five ingredients listed, in some form or another, is sugar. From peanut butter to bread crumbs, this sweetener is present everywhere in our daily lives.

A sample bilingual U.S. food label reflecting recent FDA labeling requirements (Fda.gov).

The ruling of E.C. Knight played an important role in that list of ingredients, and it stands as a major contributing factor for many of the current health problems resulting from sugar consumption.

The facts of the case involved the American Sugar Refining Company’s (ASR, commonly referred to as the “Sugar Trust”) 1891 purchase of four sugar refineries in Pennsylvania. The government subsequently filed charges against the companies alleging that the acquisitions violated the Sherman Anti-Trust Act because ASR would obtain 98% control over all the sugar refineries in the United States.

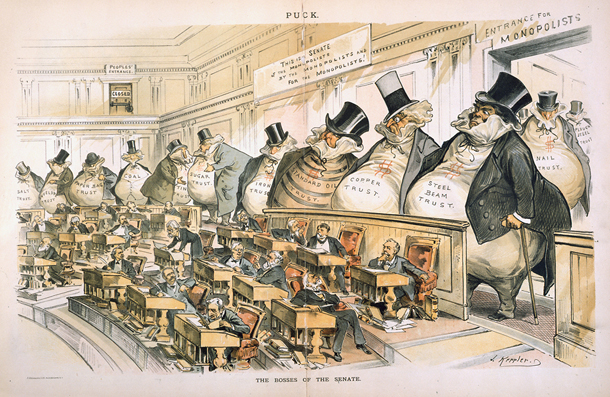

Notably, E.C. Knight was one of the first cases where the Federal government attempted to control one of the monopolies—in the form of trusts—that had proliferated after the U.S. Civil War.

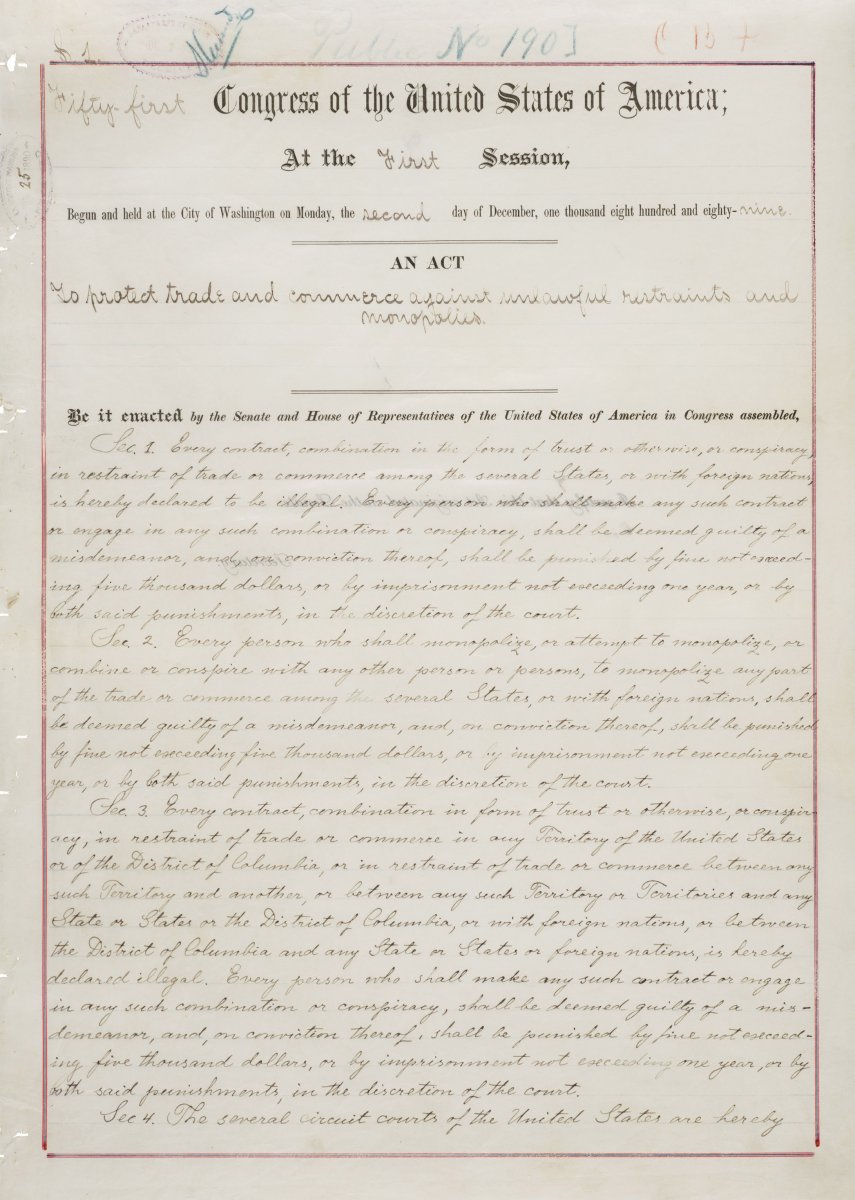

One of the twenty-two named defendants, who were mostly owners of the businesses being purchased, was Claus Spreckels. He controlled most of the sugar refineries in the Western United States and maintained a sizable ownership of sugar plantations throughout the Kingdom of Hawaii.

Claus Spreckels controlled most of the sugar refineries in the Western United States and was dubbed “the Sugar King of the Sandwich Islands” by industry insiders.

The industry dubbed Spreckels “the Sugar King of the Sandwich Islands.” With his stronghold in the islands and his own fleet that regularly traveled to and from Honolulu to San Francisco, Spreckels had developed the ideal vertical distribution channel—growing, transporting, and processing sugar throughout California.

Another named defendant was the ASR Secretary-Treasurer John Searles, who carried out clandestine sales, absorbing small refineries for the ASR.

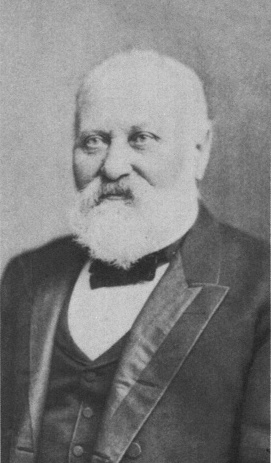

A 1918 image (left) shows the interior of a Western Sugar refinery; sugar today (right) comes in many forms.

Notably absent from the lawsuit was the ASR President, H.O. Havemeyer, who was referred to as the “Sugar Pope.” He allegedly carried out the day-to-day adjustments in sugar production through his Wall Street office. His work led to ASR’s dominance on the East Coast of the United States.

This conspicuous absence of Havemeyer from the litigation as well as other ASR executives foreshadowed the outcome of the case.

Chinese laborers work a sugar plantation in 19th century Hawaii.

A review of the transcript a century later reveals that the U.S. Justice Department was at a disadvantage. The defense counsels were more experienced (and handsomely paid in their representation of their clients). By contrast, the prosecutors had limited funding and appeared, at times, to scurry on legal enforcement of the newly enacted antitrust law.

During this period, ASR and Spreckels had been fierce competitors. By 1891, however, evidence indicates that they had started to collude. ASR had purchased Spreckels’s Philadelphia refinery and were collaborating in the formation of the Western Sugar Refining Company (Western). In exchange for Spreckels operating Western, he sold shares of his Philadelphia refinery to Havemeyer and Searles.

An 1889 cartoon from Puck, portraying the Sugar Industry as among the “Bosses of the Senate.”

Including these facts would have proven collusion by Spreckels and ASR—a violation of the Sherman Act—but this evidence and testimony was never included in the lawsuit due to the absence of key individuals like Havemeyer in the proceedings.

On January 30, 1894, the Circuit Court Judge William Butler issued his opinion finding that the contracts all took place in Philadelphia, therefore there was no interstate contract involved and dismissed the case with costs assessed against the government. Appellate courts affirmed the original decision.

A modern-day sugar refinery.

Because these omissions were never part of the trial record, the Court of Appeals, and ultimately the Supreme Court, would not know these facts and ruled that ASR controlling a mere 98% of the sugar industry did not constitute a monopoly. Consequently, the courts permitted this industry to move forward in its conquest, receiving favorable treatment from other governmental branches along the way.

The E.C. Knight case not only unleashed the sugar industry in the United States and the rest of the world, the precedent permitted the further proliferation of other trusts that eliminated thousands of small businesses until the Supreme Court’s adoption of a new interpretation of the Sherman Act.

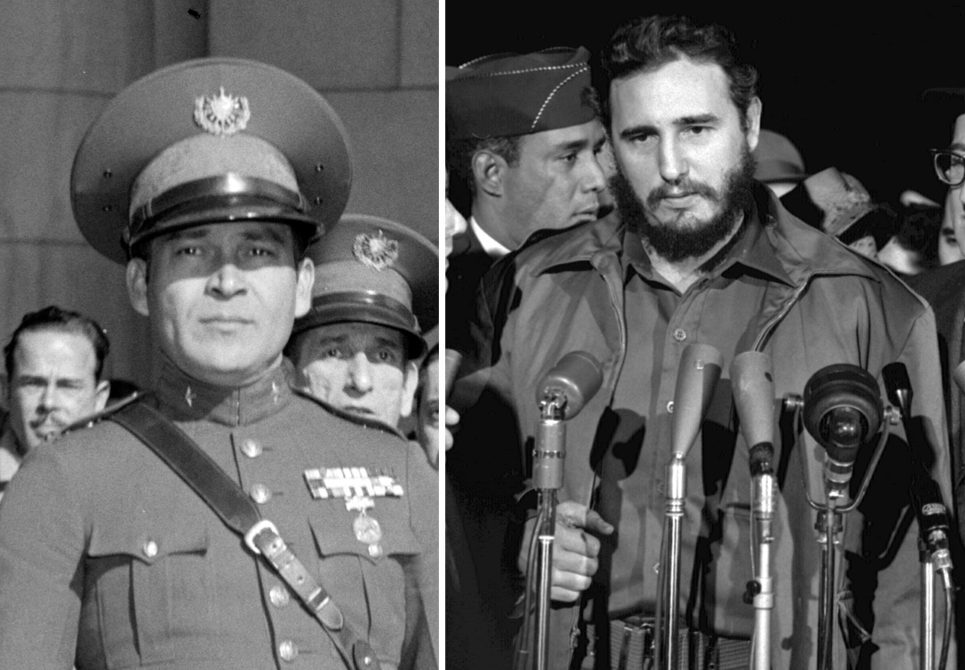

The sugar industry was closely aligned with Fulgencio Batista in Cuba; after Fidel Castro’s revolution, a Soviet trade delegation’s agreement to purchase Cuban sugar helped push the country into the USSR’s sphere of influence.

After the Sugar Trust ruling, however, the sugar industry influenced the United States’ external affairs in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Philippines, and the Kingdom of Hawaii.

The lower court’s judgment of E.C. Knight provided the foundation for an industry to proliferate. Today, we grapple more than ever with sugar's dominance in our food.

A prevalence of sugar in the modern American diet has been linked to a rise in diabetes amongst the population.