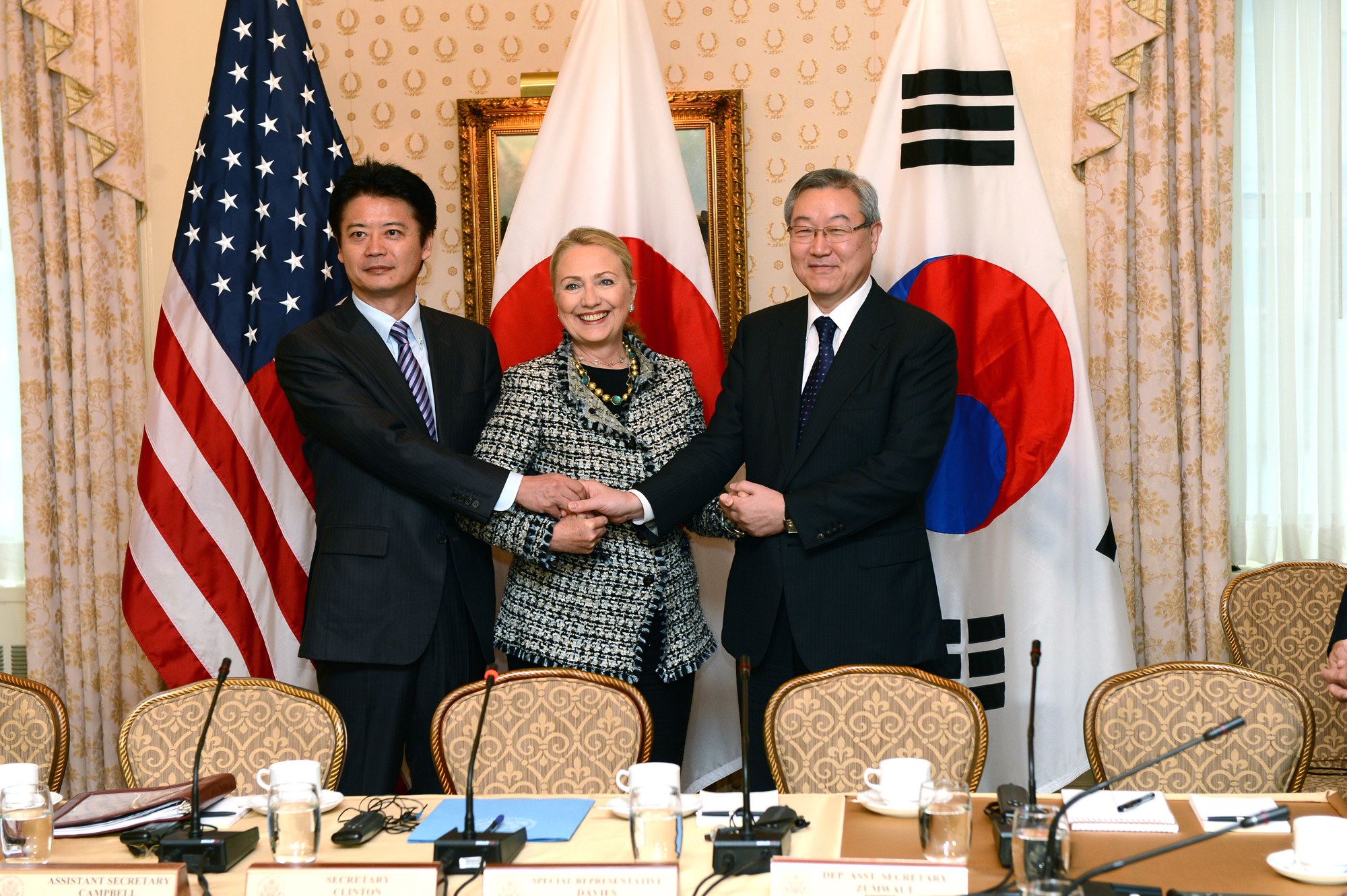

When the United States endeavored to build a new world order in the Pacific after World War II it did so assuming a close, cooperative rapport between American allies South Korea and Japan. What American policy makers discovered was an often fraught and fractious relationship between those two nations. This month, scholar Sung-Yoon Lee sketches the history of tensions between South Korea and Japan and examines why it has been so difficult for those two countries to collaborate on issues of shared importance.

Why can’t Seoul and Tokyo get Along?

“We will never again lose to Japan,” tweeted South Korean President Moon Jae-in on August 2, 2019. “We have come this far today by overcoming countless hardships. Just as we have always done in the past, we will in fact turn adversities into opportunities to leap forward.”

A casual observer of South Korea-Japan relations might mistake this statement for a rousing pep talk to the South Korean national soccer team moments before it took the field against Japan. But the very next line of Moon’s tweet implies that what is at stake is greater than the ephemeral exuberance of sports victory over Japan, Korea’s former colonial master: “2019.8.2 Emergency Cabinet Meeting.”

What prompted President Moon to convene an emergency cabinet meeting and to tweet about it to the world?

President Moon's August 2, 2019 tweet.

The immediate trigger was Japan’s announcement the same day that it would remove South Korea from its “white list” of countries receiving preferential treatment in importing sensitive goods, such as ball bearings and precision machine tools, from Japan.

Tokyo’s ostensible reason for downgrading trade relations with Seoul were “unspecified national security concerns” over South Korean companies’ alleged mishandling of materials with military applications.

But underneath those issues were tensions that had been mounting for some time between Seoul and Tokyo over issues of historical memory, legal claims of reparations by South Korean citizens over wartime forced labor, and Japan’s countermoves in the form of trade sanctions.

One of the dozens of statues dedicated to Comfort Women around the world. The statues represent Korean's struggle to have their historical memory acknowledged by the Japanese.

Through August, both sides escalated with rhetoric and measures, which left the United States, the sole treaty ally to both South Korea and Japan, exasperated in the face of successive missile tests by North Korea, a master in the art of driving wedges between Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington.

Moon’s emotional declamation that Japan is out to “defeat” South Korea again stood in stark contrast to his extraordinary restraint over the previous 11 days in the face of relentless provocations by South Korea’s other neighbors—China, Russia, and North Korea.

On July 22, Chinese and Russian warplanes staged a combined drill, flying through South Korea’s Air Defense Identification Zone while another Russian plane brazenly entered South Korean airspace. Both exercises were unprecedented.

The following day, North Korean leader Kim Jong Un showed off an upgraded nuclear submarine likely capable of launching multiple nuclear warheads. Two days later, Kim “guided” the launch of new ballistic missiles capable of hitting every part of South Korea.

A ballistic missile at North Korea Victory Day, 2013.

Over the course of those 11 days, Moon uttered not a word of complaint—not even a perfunctory statement of “regret”—in person or in any written form.

When it comes to Japan, even the slightest insult as perceived by South Koreans demands a fiery response. Such are the political dynamics in South Korea where the historical memory of Japan’s colonial oppression still remains raw and shapes politics. To exercise restraint, therefore, is to come across as weak on Japan, which is anathema to one’s political fortune.

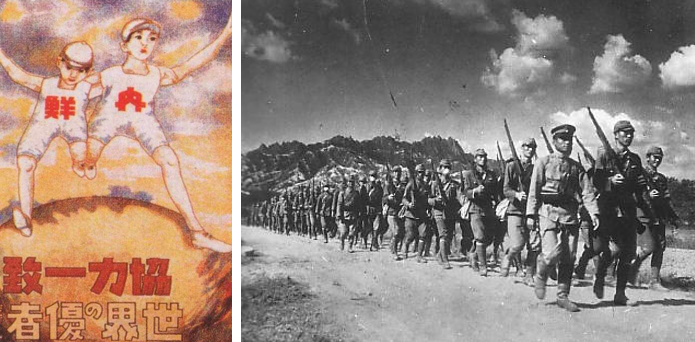

Japanese colonial rule in Korea (1910-1945) was exceptional in several aspects: Colonizers and colonized shared racial heritage and lived in geographical proximity, with greater shared cultural and historical experiences than other colonial relations at the same time (especially European colonial control in Africa, the Middle East, and Asia).

The scope and intensity of Japanese oppression are distinctive as well. Japan prohibited the speaking of Korean in schools and forced Koreans to adopt Japanese family names and Shintoism as their religion. They forcibly repatriated tens of thousands of Korean men as laborers and women as sex slaves. The intensity of Japanese participation in the colonial experience is unparalleled.

A postcard—or possibly a poster—published during Japan’s naisen ittai campaign in occupied Korea translated as: "Japan-Korea. Teamwork and Unity. Champions of the World" (left). Korean conscripts into the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), 1943 (right).

By the end of World War II, some 700,000 Japanese resided in Korea. Rule by the Japanese state was characterized by thought control, mass mobilization, and ruthless nationalistic purpose, enabled by a powerful bureaucracy, arms, and communications.

Hence, stirring up anti-Japanese feelings in South Korea has long served to improve one’s political approval ratings. Each of Moon’s predecessors, whether “conservative” or from the same “progressive” camp as Moon, has used the anti-Japan card to score political points, much to the consternation of the United States, which views the trilateral alliance among the three nations as key to deterring China, North Korea, and Russia.

These dynamics—leftovers from the Cold War, Seoul’s residual antipathy toward Tokyo, and the primacy of security interests for Washington—have governed the international politics of the region for over seven decades.

Japan, Korea, and the Legacy of World War II

Since 1945, Japan has risen to become a model of democracy and peace. In his 1971 memoir The White House Years, Henry Kissinger wrote that “Japanese decisions have been by far the most far-sighted and intelligent of any major nation of the postwar era.”

Kissinger admired the U.S. occupation of Japan from 1945 to 1952 led by General Douglas MacArthur, during which Japan’s constitution was overhauled and the nation became a peaceful parliamentary democracy.

Japan’s pragmatic policy of depending on the United States for security while focusing on its economy, enabled a stunning economic revival. Four decades after Kissinger’s comment, it remains difficult to disagree with his flattering assessment.

The Korean peninsula, however, underwent a different postwar experience. Brutally occupied by Japan since 1910, Korea’s liberation included a hasty division of the country itself. The Soviet Union occupied the north while the United States occupied the south.

Korea became perhaps the first site of confrontation in the new Cold War. In 1948, elections in the south elevated the American-backed Syngman Rhee to the presidency while the Soviet Union installed Kim Il-sung as head of North Korea.

South Korean general election on 10 May 1948. This election elevated Syngman Rhee to the presidency.

The next year, the United States, in spite of having governed South Korea for three years, effectively abandoned it by withdrawing U.S. troops, leaving the Rhee regime vulnerable to the North.

In June 1950, war broke out when North Korea invaded South Korea in an attempt to reunify the country. The United States, with the backing of the United Nations, launched a counter-attack. The Korean War lasted until 1953 without any formal end and the peninsula remains divided along the 38th parallel.

Japan, therefore, enjoyed peace, stability, and economic prosperity after its defeat in World War II while Koreans had to confront the trauma of Japanese occupation and the Korean War.

South Korea experienced rapid economic growth beginning in the 1960s but it did so under a series of repressive regimes and considerable political turmoil. South Korea became a democracy in the 1990s with the end of military commander-turned-president governance in the 1990s. At the same time, North Korea became an international pariah state ruled by the despotic Kim family.

Japan’s historical revisionism, deflection, and denial regarding its past war crimes against Koreans and Chinese—including massacres of civilians, military sexual slavery, and forced labor—have continued to cloud its otherwise attractive international image.

Because most South Koreans believe that Japan has yet to admit legal culpability and offer appropriate reparations, South Korean leaders strategically avoid appearing soft in any rift with Tokyo.

South Koreans believe almost unanimously in the need to take a firm stand against Japan. This is particularly true on the very sensitive issues of “comfort women”—tens of thousands of Korean girls and women who were forced into sexual slavery by the military to provide “comfort” to Japanese soldiers at “comfort stations” dispersed throughout Japan’s empire in the Asia-Pacific—and Japan’s whitewashing of war crimes in official government statements and history textbooks. It is also manifest in the ongoing territorial dispute over islets in the East Sea (or “Sea of Japan”) called “Dokdo” in Korean and “Takeshima” in Japanese.

More than setting the record straight or protecting national interests, standing up to Japan—even to the point of self-defeating excess—is a matter of national honor and patriotism.

While Japan has made several official apologies in the past, successive Japanese leaders, including Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Junichi Koizumi, have diluted or even denied their predecessors’ apologies with inflammatory acts as well as obfuscatory and revisionist statements.

For a Japanese prime minister to visit the controversial Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo, where 14 Class-A war criminals are enshrined, as Abe has, or to question the veracity of testimonials by former “comfort women”—even as there are some inconsistencies in their recollections of events nearly 50 years old and in view of the fact that hundreds of victims came forward in the 1990s—is to ignite the flames of anti-Japanese sentiment in Korea, China, and beyond.

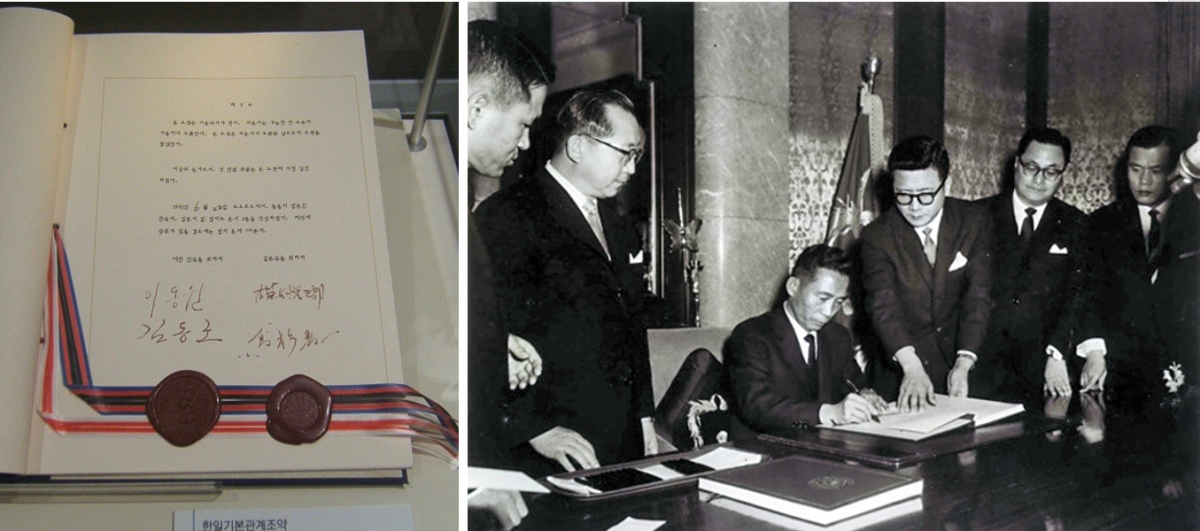

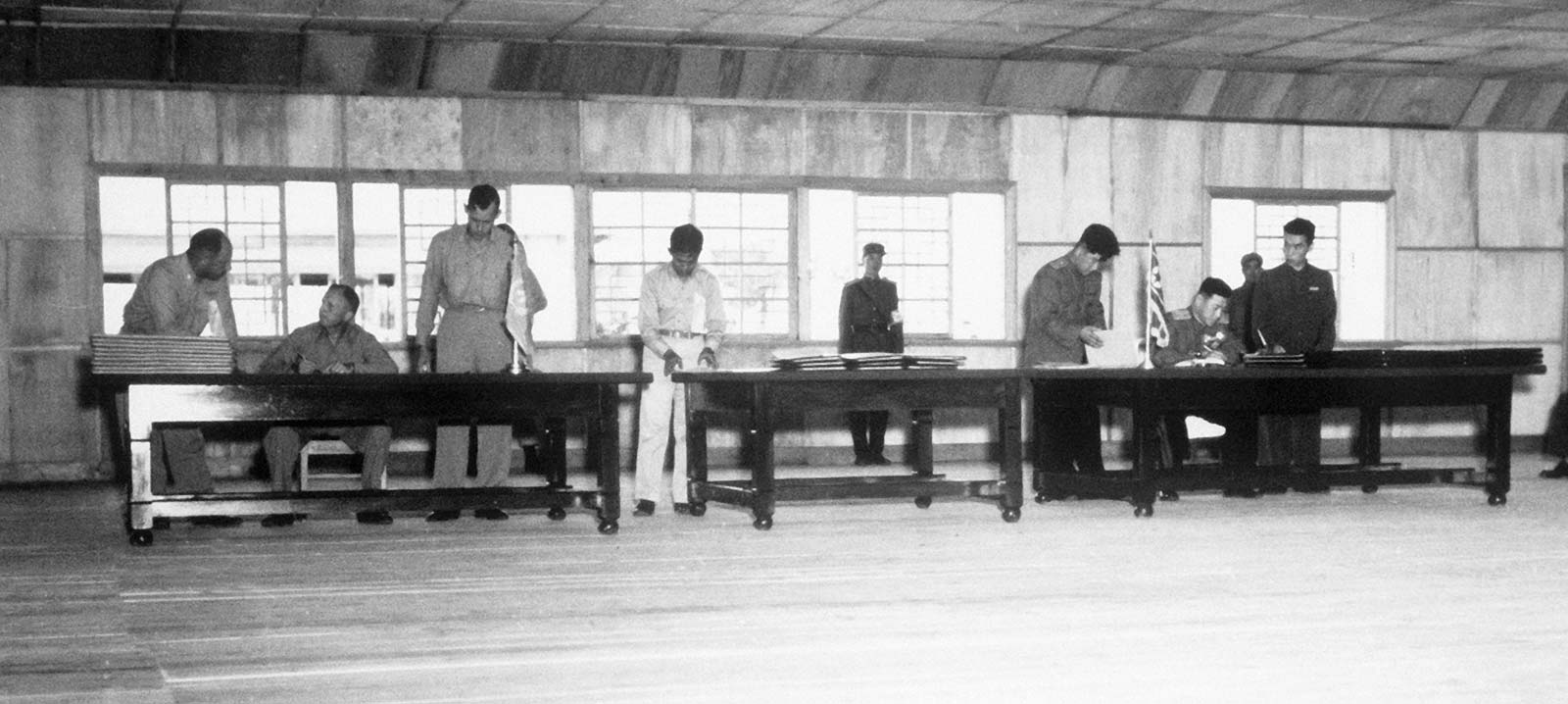

In June 1965, Japan and South Korea signed a treaty to normalize diplomatic relations. Article II of the treaty states that any “problem concerning property, right, and interests” between the two nations and “their nationals (including juridical persons)” was “settled completely and finally.”

Pursuant to the terms of the treaty, Japan provided South Korea with $500 million in grants and long-term, low-interest loans disbursed over a decade, as well as an additional $300 million in loans for private trust.

Japan’s payments were described as “economic cooperation,” not reparation. In fact, the treaty is named “Agreement on the settlement of problems concerning property and claims and economic cooperation.” In ratifying the treaty, South Korea, in effect, renounced all rights to seek further compensation.

A copy of the Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea exhibited at the National Museum of Korean Contemporary History (left). President Park Chung Hee signs the treaty to normalize relations between Korea and Japan on December 17, 1965 (right).

Tensions rooted in the legacy of World War II erupted in October 2018 when South Korea’s Supreme Court issued a ruling ordering Japan’s Nippon Steel & Sumitomo Metal to pay 100 million won, or about $88,700, to each of four South Korean plaintiffs who said they were victims of wartime forced labor between 1941 and 1943. Koreans saw this as justice long-delayed while Japanese widely viewed the ruling as a political move.

In November, Seoul’s Supreme Court issued a similar ruling, ordering Mitsubishi Heavy Industries of Japan to pay each of five women sums ranging between about $89,000 and $133,000.

Tokyo strongly protested these rulings. While Mitsubishi called the court order “deeply regrettable,” Foreign Minister Taro Kono called the rulings “totally unacceptable,” claiming in a written statement that they “completely overthrow the legal foundation of the friendly and cooperative relationship.” Japanese officials and many citizens believed both rulings violated the 1965 treaty.

On the other hand, the South Korean Supreme Court’s rationale for the ruling was that the 1965 normalization treaty “does not cover the right of the victims of forced labor to compensation for crimes against humanity committed by a Japanese company in direct connection with the Japanese government’s illegal colonial rule and war of aggression against the Korean Peninsula.”

This is a weak legal argument because the 1965 treaty predates the establishment of the International Criminal Court (ICC) per the Rome Statute in 1998. The ICC has jurisdiction over crimes against humanity cases (as well as cases pertaining to genocide and war crimes) and jurisdiction only with respect to crimes committed after the entry into force of the Statute.

Moreover, forced labor, although a serious crime, does not fall under the definition of “crimes against humanity” under Chapter 7 of the Rome Statute. Japan’s claim that South Korea’s Supreme Court issued political judgments, while diplomatically ill-advised and inflammatory, is valid.

At the same time, Kono’s admonition that South Korea should take “immediate actions to remedy such a breach of international law” exacerbated the problem and deepened South Koreans’ view of Japan as unrepentant.

Japan claims that recent South Korean administrations have been “moving the goalposts,” reneging on previous bilateral agreements and calling on the Japanese government to make one apology after another. Yet the lingering—perhaps growing—anti-Japanese sentiment in South Korea is largely the product of Japan’s own words and deeds.

Few outside Japan would deny that Japan has failed to confront its wartime atrocities. That failure continues to plague Japanese relations with South Korea and China.

The United States—Major Player or Helpless Bystander?

American policymakers have long been frustrated by periodic spats between Seoul and Tokyo dating back to the Korean War of 1950-1953. The exigencies of war and its unsatisfactory end in a ceasefire created a need for Washington to galvanize allies and resources to bolster its containment doctrine in East Asia and beyond.

Hence, the United States exhorted South Korea and Japan, now both dependent on it for national security, to mend fences. However, each round of talks in the 1950s ended disastrously, yielding more animosity than agreement. The meeting in October 1953 in particular, coming just three months after the ceasefire agreement in July, reached the apex of acrimony.

Kubota Kanichiro, Japan’s lead delegate in the 1953 bilateral talks with South Korea, remarked that South Koreans are “servile to the powerful, and high-handed toward the weak.”

He claimed that the United States had violated international law by liberating Korea and supporting the establishment of the Republic of Korea (the formal name of South Korea)before concluding a peace treaty with Japan, in redistributing Japanese-held properties in the Korean peninsula to South Koreans, and in repatriating Japanese nationals.

The outspoken diplomat also said Koreans should be grateful for all the improvements Japan had made in Korea during Japan’s “compulsory occupation.” He highlighted in particular the construction of railways, ports, and farmland, which “was beneficial to the Korean people.” For the next five years, no bilateral meetings between Seoul and Tokyo took place.

Another low point in the South Korea-Japan relationship and in the Seoul-Tokyo-Washington triangle came in 2005.

The Liancourt rocks, in Japan called Takeshima and in North and South Korea called Dokdo.

In February, Japan’s Shimane Prefecture, invoking the decision a hundred years earlier placing “Takeshima” (Dokdo) under its jurisdiction, designated February 22 as “Takeshima Day.” South Korean President Roh Moo-Hyun (for whom Moon Jae-In was the top aide), riposted that South Korea was on the verge of a “diplomatic war with Japan” and that he would “eradicate the roots of the problem.”

Roh’s inflammatory rhetoric drew inflammatory responses from Japan. The Nikkei Shimbun questioned Roh’s leadership, painting him as one “easily swayed” by public opinion, even calling his emotional response “just like North Korea.”

Yet Roh’s approval rating jumped from 30 percent to 48 percent in just four days, with 89 percent of South Koreans supporting his feisty remarks. The lesson was clear: It paid to antagonize Japan when the South Korean public felt Japan had been the provocateur.

Stirring up anti-Japanese sentiment when in political trouble has also proven successful.

Street sign in Seoul, 2012 (left). The Korean flag flies over Liancourt Rock's East Islet with the West Islet in the background, 2009 (right).

In August 2012, Roh’s successor, President Lee Myung-Bak, was bogged down in corruption scandals involving his closest aides including his own brother. He flew by helicopter to Dokdo, the contested islet under South Korean administrative control. Lee was the first South Korean head of state to visit the disputed territory.

“Dokdo is truly our territory, and it’s worth defending with our lives,” Lee declared to the squadron of South Korean police officers guarding the islets, deliberately fanning the flames of Korean ethnonationalism.

Prime Minister Yoshihiko Noda condemned Lee’s visit as “completely unacceptable,” pledging to take a “resolute stance on this matter,” while his foreign minister characterized the visit as “utterly unacceptable” and recalled his ambassador in Seoul.

As tensions soared in the summer of 2019, Americans once again were flabbergasted.

Following his “We will never again lose to Japan” tweet, President Moon went further. During his “Liberation Day” speech on August 15 (once known as “Victory over Japan Day” in the United States), Moon spoke of “the road to overtaking Japan and guiding it toward a cooperative order in East Asia.”

President Moon's Liberation Day speech on August 15, 2019.

Moon raised the ire of the United States even more by proceeding with South Korea’s withdrawal from the General Security of Military Intelligence Agreement (GSOMIA), an intelligence-sharing deal with Japan that is strongly supported by Washington.

Both the U.S. and Japan protested with, by the standards of diplomacy, strong language, expressing “deep concern and disappointment.” Washington said the move reflected a “serious misapprehension on the part of the Moon Administration regarding the serious security challenges we face in Northeast Asia.”

That South Korea decided in late-August, 2019 to scrap its pact with Japan even in the wake of seven separate missile tests by North Korea since July 25 alone and in the face of Japan’s considerable superiority in signals intelligence (SIGINT), including superior satellites, ground stations, and radar on planes and ships came across to Washington as irrational and self-defeating.

It seemed Moon was more interested in fanning the flames of anti-Japanese sentiment for political gain and placating a North Korean regime bent on threatening and deriding the South Korean government, including President Moon himself at the cost of the security interests of the U.S. and South Korea itself.

To further drive home the point, on August 25 South Korea conducted the largest scale-ever military drills in defense of Dokdo (Takeshima). It seemed to the U.S. an over-the-top measure designed to boost Korean ethnonationalism and irritate Japan. While these measures were less provocative than former President Lee’s visit to Dokdo in 2012, they still signaled to Washington and others that the Moon administration was willing to go beyond tit for tat when it came to Japan.

The renewed hostility between Japan and South Korea may also serve to send messages to North Korea.

Under President Donald Trump, U.S. policy in Asia has become erratic and less effective. Trump’s splashy summit with North Korean leader Kim Jong-un did not yield substantial results. South Korean leaders, however, have recently made significant overtures to the North. North Korea’s reluctance to engage, perhaps because of the corona virus outbreak, has put a halt to those discussions.

Can the Status Quo Be Changed?

One year after Japan announced export controls and protested South Korea’s firing warning shots at a Russian plane in Dokdo airspace, the bilateral relationship remains frozen in time.

In June 2020, Seoul requested that the World Trade Organization review Japan’s export restrictions on semiconductor materials. As expected, Japan balked, with the nation’s trade minister calling Seoul’s action “extremely regrettable.”

Sign stating that Dokdo belongs to South Korea, 2010.

On July 13, Japan published its annual defense white paper. For the 16th year straight, the white paper asserted a territorial claim over Dokdo. The South Korean government lodged a formal complaint, its foreign ministry calling Tokyo’s claim “unjust and absurd.”

For the United States to mediate between its two key allies in East Asia amid accelerating tensions serves U.S. national interests. At the same time, stopgap measures and alliance management alone cannot resolve the problem, as the roots of it lie in the hardened perception gap among South Korea, Japan, the U.S.—and, pointedly, North Korea.

These disparate national perspectives are here to stay, reinforced by colonial oppression and war, exacerbated over time by ethnonationalism, historical revisionism by all sides, and political interests.

A fundamental change in the status quo in the Korean peninsula—war, humanitarian disaster, or merger of the Korean states—might impel the actors to relinquish their grievances and collaborate on building a more cooperative, common future.

While the U.S. imagines a convergence of national interests between South Korea and Japan by virtue of the growing North Korea threat, the reality is very different. The current South Korean leadership subscribe to an ideology of pan-Korean ethnonationalism. “Common bloodline comes before alliance,” as a former South Korean president said. This means warming up to North Korea comes before warming up to Japan.

Moon might prioritize reaching out to North Korea after an extended lull in inter-Korean talks following his visit to Pyongyang in September 2018, even in violation of United Nations Security Council resolutions prohibiting joint ventures with North Korea, over improving relations with Japan or allaying U.S. concerns.

Recreating the drama of summit pageantry and promoting illusions of the denuclearization of the North even while being high-handed toward Japan would still mean a political victory. Why? Because the South Korean public will support it.

A 2005 rally demanding acknowledgment and compensation for comfort women.

Short of Japan’s coming clean on its past war crimes, making reparations to Korean victims of sexual slavery and coerced labor, and radically revising its history textbooks, South Korea will find it next to impossible to shed its residual antipathy and embrace Japan as a friendly neighbor. Yet these measures remain unlikely.

In the end, genuine reconciliation between the peoples and governments of South Korea and Japan is likely to happen only when a fundamental change in the status quo in the Korean peninsula entails Japan’s proactive participation in military and humanitarian operations there.

For Japan to be a stakeholder in forging a new, peaceful regional order in Northeast Asia will mean going beyond providing humanitarian aid and disaster relief. It will require sustained financial contributions in the rebuilding of what is present day North Korea. The extent of Japanese contributions will come to define the nature of Japan’s relations with its new Korean neighbor.

Until such opportunity and need arise, South Korea and Japan will maintain their awkward, lukewarm friendship, fluctuating between warming up to and turning their backs on each other, while remaining determined not to lose.

Read and Listen more on East Asia: Japanese Nuclear Power; Hiroshima; North Korea; The Myth of a Hermit Kingdom; Nuclear North Korea; Hong Kong in Protest; Hong Kong and China; Remembering Tiananmen; The United States and China; The China Dream; The Greening of China?; China and Africa; Taiwan’s Politics; The Chinese Cultural Revolution; and A Postcard from Yeongju, South Korea

Scott Snyder and Brad Grosserman, The Japan-South Korea Identity Clash: East Asian Security and the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 2015).

Tessa Morris-Suzuki et al., East Asia Beyond the History Wars: Confronting the Ghosts of Violence (London: Routledge, 2015).

Gregory Henderson, Korea: The Politics of the Vortex (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1968).

Alexis Dudden, Troubled Apologies Among Japan, Korea, and the United States (New York: Columbia University Press, 2008).

Carter J. Eckert, Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866-1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016).

John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (New York: Pantheon Books, 1986).