Politics in Hong Kong are at a boiling point as we go to press. For weeks street demonstrators have clashed with police as the government has tried to walk a fine line between meeting local demands and satisfying the instructions issued by the People's Republic of China. Ostensibly, the origin of this unrest lies in the handover of power from the British to the PRC in 1997, and the complicated governance structure that that handover created. But as historian Melvin Barnes demonstrates, the conflict between Hong Kong and Beijing has much deeper roots and this month he gives a primer on the political history of Hong Kong.

In the renowned Hong Kong crime thriller Infernal Affairs (2002), the film’s two main characters struggle to remember who they really are as they spend years undercover on opposite sides of the battle between the Hong Kong Police Force and the criminal Triads. For the movie’s two leads, living in two different worlds generates fear about the loss of self and anxiety about the future.

While Infernal Affairs is a work of fiction, its theme of psychological pressure from being trapped between worlds can help us understand the unrest that has rocked Hong Kong in recent weeks.

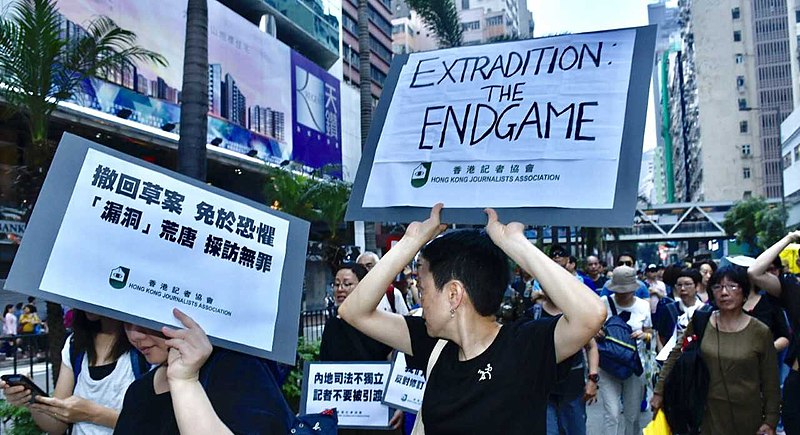

Since March, millions of Hong Kong’s citizens have engaged in historic protests against a controversial extradition bill. Under the agreement proposed by Hong Kong’s Security Bureau in February, criminals apprehended in Hong Kong could be extradited to the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

The bill was introduced after Chan Tong-kai murdered his girlfriend, Poon Hui-wing, while the two Hong Kong residents vacationed in Taiwan. Chan eventually returned home but evaded murder charges because he committed the crime outside of Hong Kong’s jurisdiction. He is also under no threat of being sent to Taipei because Hong Kong lacks an extradition treaty with Taiwan. Citing the Chan case, the city’s authorities have moved to pass a bill that would allow for the extradition of criminals not only to Taiwan but also to the PRC.

Geographic location of China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan.

On April 28, tens of thousands of people flooded the streets of Hong Kong in opposition to the proposed law. Less than two weeks later, on June 9, demonstrations grew to over a million people, making them the largest protests in decades. Over the summer, marches, protests, and clashes with police have grown more frequent and more intense.

Hong Kong’s Chief Executive Carrie Lam, initially unmoved, stoked even greater unrest in the following days with her continued support for the bill. Yet more demonstrators turned out in mid-June, clashing with Hong Kong police. With dozens injured, the police have faced criticism for their use of tear gas and rubber bullets on unarmed protesters.

In July 2019, police gathered near an upscale mall in Sha Tin, Hong Kong, to control protesters.

Hong Kong, a former British colony, is a self-governed region of the PRC, but many of its citizens hold grave apprehensions about their place in China. Many believe that the PRC will use the bill to silence its critics in Hong Kong, eroding political liberties residents hold dear. As a self-governed region of China set to be fully incorporated into the PRC in 2047, the bill and the subsequent protests represent the struggle between Hong Kong’s British colonial past and its future as a Chinese city.

Lam’s administration stood behind the proposed extradition agreement throughout the first round of protests but ultimately suspended the bill on June 15. Her move placed the law in limbo, but it has not quelled public disapproval. Demonstrators calling for Lam’s resignation and a full withdrawal of the bill continued to take to the streets in unprecedented numbers. On July 1, the 22nd anniversary of Hong Kong’s return to China, protesters ransacked parliament and hoisted the city’s colonial flag before police could retake the building hours later.

Protesters in 2012 waving Hong Kong’s colonial flag.

Unrest has only become more intense and widespread over the summer, including extensive demonstrations against how police handled the original protests.

Political leaders in China have long used the phrase “one country, two systems” to describe Hong Kong’s relationship with China. However, Hong Kong has struggled to reconcile its two identities.

Hong Kong the Colony

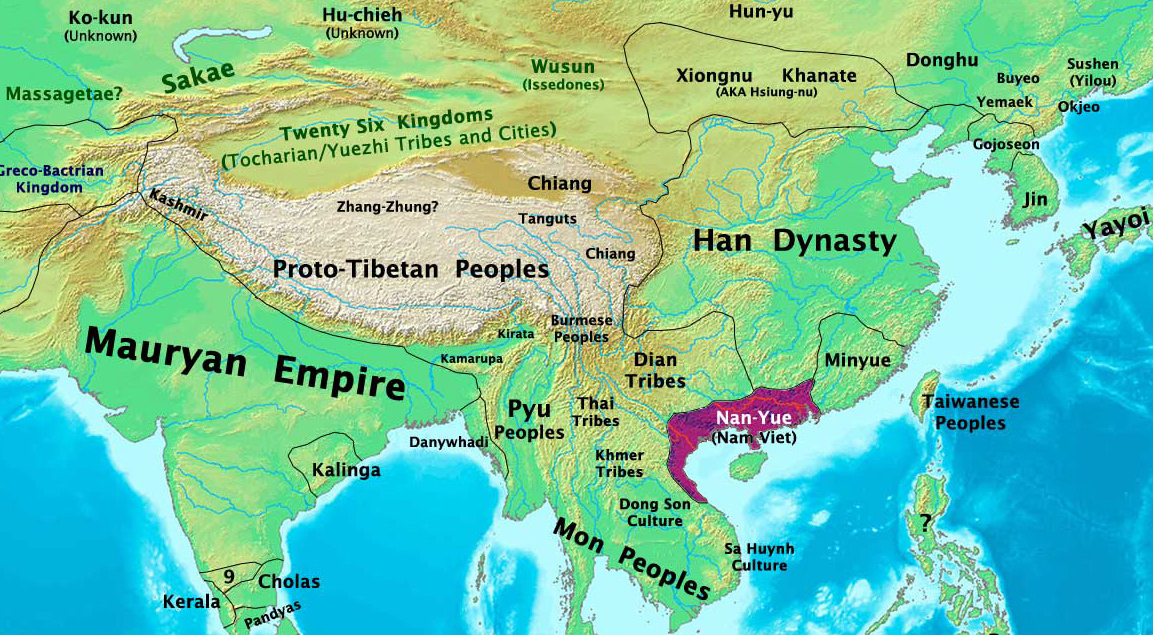

Hong Kong sits at the mouth of the Pearl River estuary in southern China, made up of the Kowloon Peninsula and more than 200 islands of various sizes. Its first inhabitants were the Yue peoples, who controlled the region until 111 BCE when the Chinese Han Empire conquered it. From that point on, the area was closely integrated into subsequent Chinese dynasties. Communities of fishermen, farmers, and local businesses took root there.

By the early 19th century, Great Britain presided over an empire upon which the sun never set. British merchants made increasing contact with the Chinese Qing Empire (1644-1911), then the largest economy in the world. Qing China produced goods such as tea and silk that British subjects desired but could not find elsewhere.

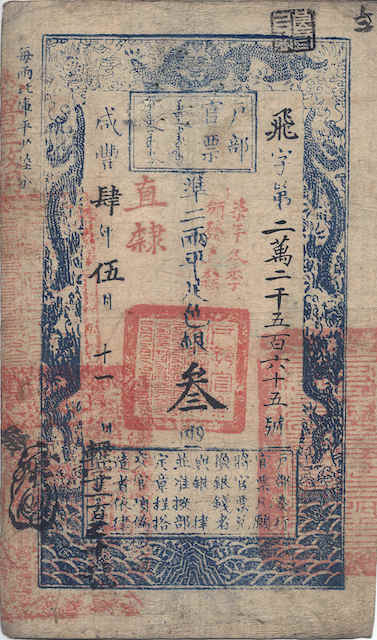

Unfortunately for the British and other European traders, foreign merchants possessed little that the Chinese valued beyond silver. The Qing managed trade through the Canton System, which limited exchanges to a small group of merchant houses in Canton, now Guangzhou, open just five months out of the year.

Despite strict trade limitations, business was lucrative given the high value of Chinese commodities. Silver flowed into China’s economy from the outside world—until the mid-18th century.

Qing dynasty paper banknote representing silver ingots, circa 1854.

The British finally acquired a commodity to trade with China: Bengali opium from India. Opium had been used in China for medicinal purposes for centuries, but under the Qing, it became a controlled substance as more and more Chinese smoked the drug as a recreational narcotic.

Between 1729 and 1767, the number of imported chests of opium grew fivefold from 200 to 1000. After 1761, the British East India Company began smuggling large quantities of opium into China in defiance of Chinese trade restrictions and an outright ban on opium imports.

Due in large part to this drug trade, the torrent of silver that once flowed into China reversed, diminishing local tax bases. The Daoguang Emperor took drastic action in 1838 to address the issues caused by the recreational use of opium and its illicit trade. The emperor sent Lin Zexu to southern China to take control. Opium smokers were given a year to kick the habit and smuggling was brought to a halt.

The Daoguang Emperor’s crackdown brought the Qing Empire into direct conflict with Great Britain. By the start of the crackdown, nearly 10 percent of Britain’s annual revenue came from the sale of opium. Lin Zexu, knowing that English law prohibited British subjects from using opium, famously asked Queen Victoria, “Where is your conscience?”

Lin Zexu, a Qing dynasty official during the First Opium War, 1839-1842.

Shortly after Lin arrived, he confiscated 21,000 chests of opium and washed the drugs into the sea. These losses, coupled with a determination to pry open Chinese markets, led the British to declare war on the Qing in 1839.

British warships blockaded the mouth of the Pearl River while others steamed up the Chinese coast to harass Beijing. As the fleet neared Tianjin, a port city 75 miles southeast of Beijing, the Qing sued for peace. Further battles followed, but in 1842 the Treaty of Nanjing created treaty ports throughout China and began the process of opening the empire to the West.

A British steamer destroying Chinese ships during the First Opium War in 1842.

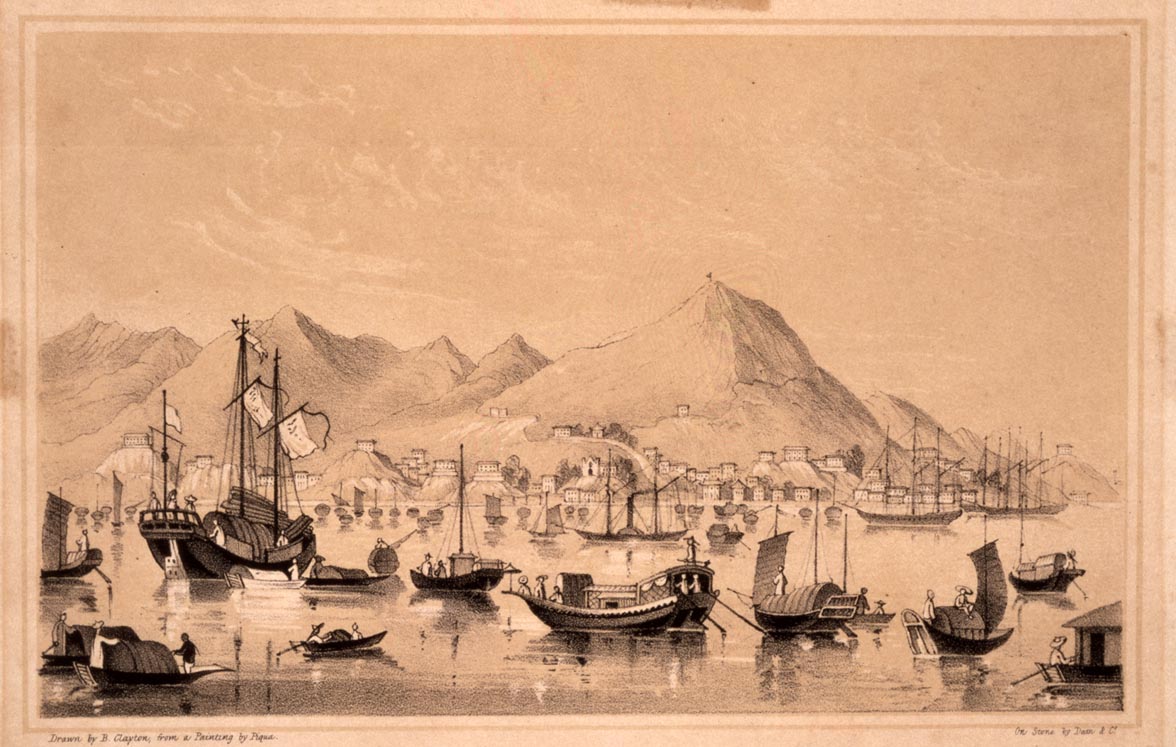

Even more devastating, the Qing were forced to pay a massive indemnity. Hong Kong Island, though not necessarily considered all that important by the Qing, was ceded to Great Britain “in perpetuity.” British Hong Kong emerged from a literal empire of narcotics.

The British acquired Hong Kong to facilitate trade with China and to establish a strategic military outpost. When the island was absorbed into the empire, its population was less than 10,000, a figure that doubled within the first few years of British administration. However, its governance developed at a modest pace, with the structures of colonial administration popping up over time.

Hong Kong in 1850 after British acquisition.

Like other colonies around the world, British Hong Kong succeeded through local cooperation. Chinese laborers built many of Hong Kong’s palatial structures and contributed to British colonial administration. The British hoped that Hong Kong would attract wealthy Qing tradesmen, but despite the colony’s seemingly rapid development, things got off to a rocky start.

British Hong Kong began as a trading space for Westerners, South Asian businessmen, and Chinese merchants. This mixing of peoples made misunderstandings common while the initial weakness of the new colonial government allowed crime to soar. Pirates and thieves regularly raided warehouses and burgled homes. The unsafe environment and the Qing’s reluctance to allow its subjects to do business on the island scared off Chinese merchants, undercutting profits and calling into question the founding goals of the colony.

A battle scene during the Taiping Rebellion, from 1850-1864.

Hong Kong would remain just a distant British outpost until the Taiping Rebellion, the most destructive civil war in human history, from 1850 to 1864. Hong Xiuquan, the leader of the iconoclastic Taiping Heavenly Kingdom and proclaimed brother of Jesus Christ, set about toppling the Qing Empire and establishing a Christian empire in China. The war devastated China, pushing the Qing to their breaking point and costing between 20 and 30 million lives.

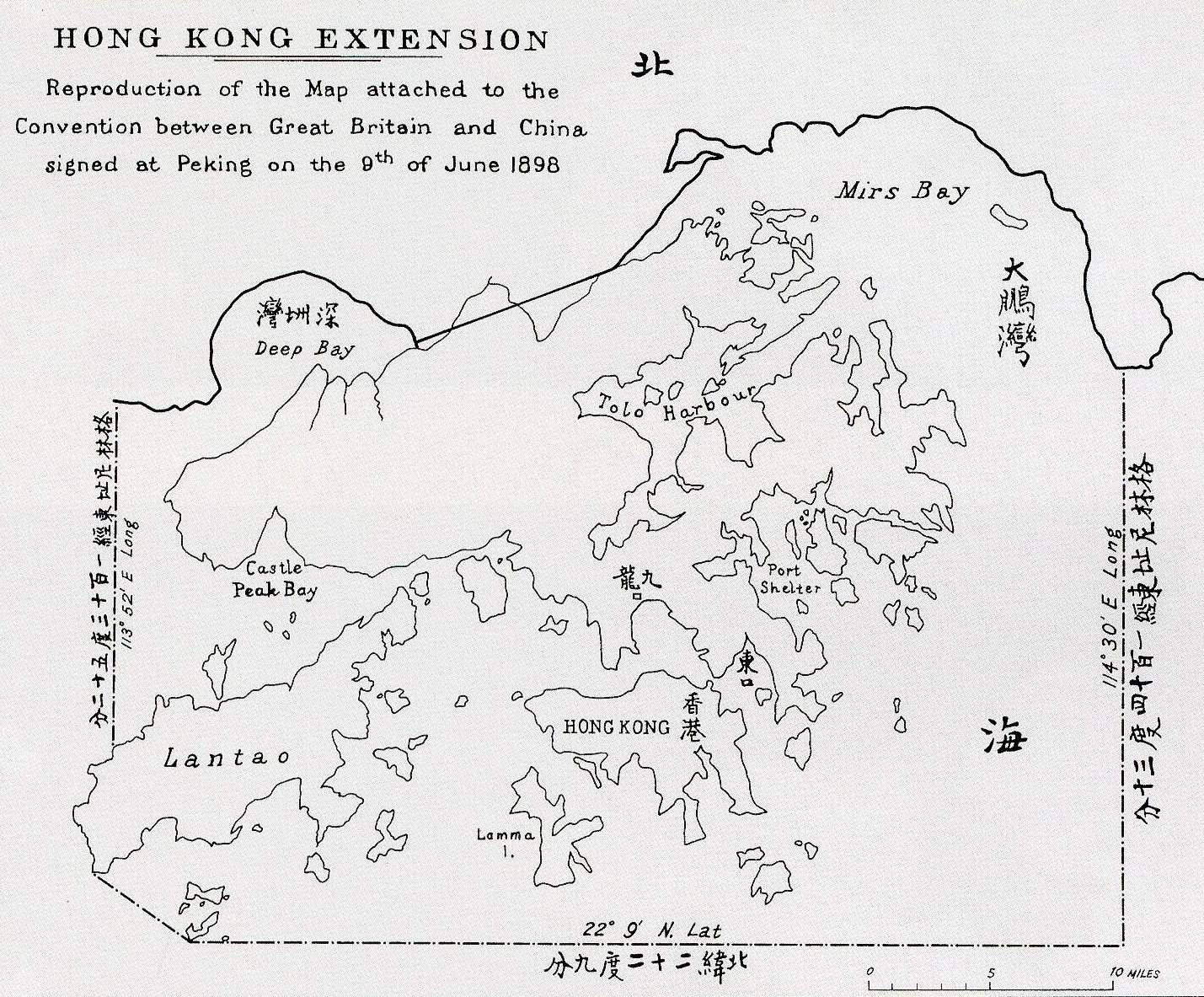

Fleeing the turmoil, wealthy merchants and ordinary subjects poured into the relative safety of Hong Kong. In 1898, Britain signed a new lease gaining the “new” territories on the Hong Kong peninsula across from the island.

An 1898 map of Hong Kong and the “new” territories on the peninsula that were leased to Britain.

This new lease was to last 99 years, but many believed it would never expire. The expansion of the territory and the influx of people and money set colonial Hong Kong on the path toward growth, though it was still far from the booming metropolis it would become in the mid-20th century.

The Sun Sets on the British Empire and Rises Over Hong Kong

The economic success in Hong Kong today is rooted in the decades following World War II and the Cold War. The civil war between the Chinese Communist Party and their nationalist rivals forced over a million Chinese to migrate to Hong Kong between 1945 and 1949, lifting the city’s population to roughly 2.5 million.

Chinese refugees at the Hong Kong border in 1950.

Yet, Hong Kong faced Cold War restraints such as embargos that limited its exchange with the PRC. Goods that were difficult or impossible to find in the PRC due to the American and U.N. embargos were smuggled in via Hong Kong.

The trade barriers led Chinese entrepreneurs in Hong Kong to invest in other opportunities such as light industries. Due to these changes, the city’s steady colonial government, access to British capital, and an influx of cheap labor from China, Hong Kong entered its postwar economic boom fueled by industrial growth.

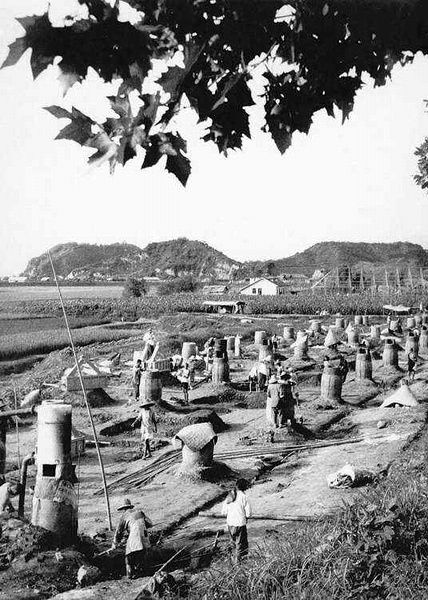

Textile manufacturing soared in Hong Kong in the 1950s.

During this time, stark differences between life in Hong Kong and the PRC led to a singular Hong Kong identity.

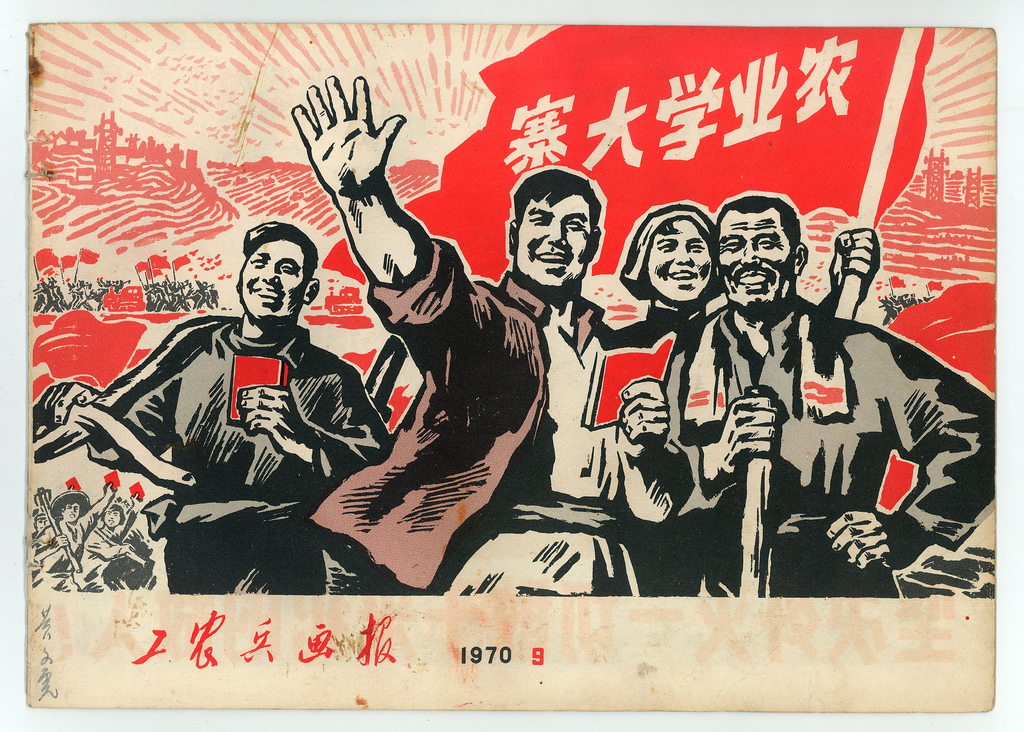

The PRC overcame enormous difficulties but also suffered massive unrest during its first 25 years. Mao’s Great Leap Forward (1958-1962) crippled China’s economy and caused a devastating famine. Less than 10 years later, the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) unleashed political factionalism that touched every quarter of PRC society and further damaged the economy.

Mao’s Great Leap Forward encouraged steel production in backyard furnaces, circa 1958.

By contrast, Hong Kong enjoyed a strong economy despite its own unrest in the 1960s. Between 1968 and 1972, the city’s GDP grew by over 100 percent. As the PRC became more open to the outside world in the late 1970s, travel to China confirmed just how different the two places had become during more than a century of colonial administration.

At the same time, the city began to enjoy greater autonomy from Britain. By the 1970s, Hong Kong’s colonial administrations controlled its foreign reserves and managed its economic policies. As the economy expanded, Hong Kong embraced its ambiguous identity, neither fully Chinese nor British.

Billboard of Deng Xiaoping erected in 1992 in Lizhi Park, Shenzhen, China.

As the PRC opened to the world following Deng Xiaoping’s rise to power, manufacturing in Hong Kong declined. From the late 1970s into the 1980s, nearly 90 percent of Hong Kong’s factories moved to Guangdong in the PRC. Undeterred, Hong Kong transitioned successfully into a service-based economy and is now one of the most important financial and shipping centers in the world with a per capita GDP similar to that of the United States.

Given the city’s unique history and continued success, many in Hong Kong hoped that the city would one day become fully independent, existing as a British Commonwealth.

Hong Kong protesters demanded universal suffrage in 2008.

But a true representative democracy wherein Hong Kong’s citizens elected their chief executive never fully materialized. A movement toward creating direct democratic elections with universal suffrage gained steam in the late 1980s and 1990s. However, the process was not completed before the British handover in 1997. If direct elections had come to the city, perhaps Hong Kong could have chosen its own fate. As a colony, the city and its citizens scarcely could control the future.

The Return

For much of the 1950s and 1960s, the PRC insisted that recovering Hong Kong was not a top priority, though if the city were to be returned it would be done so peacefully. In fact, the PRC may have even worked to help maintain Hong Kong’s status during those years in order to maintain its window to the outside world.

By the 1980s, however, the PRC’s priorities changed. China began the process of transforming its economy and opening to the world in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Like its East Asian neighbors Japan and South Korea before it, China experienced an unprecedented economic boom.

In the midst of this social, political, and (notably) economic transformation, the PRC and Britain began negotiating the peaceful return of Hong Kong to China. These negotiations resulted in the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1985, with the result that Britain agreed to return the city to China in 1997.

A replica of the historic negotiations in 1984 between Deng Xiaoping and Margaret Thatcher to return Hong Kong to the PRC. The exhibit is on display in the Meridian View Center, located on the 69th floor of the Diwang Mansion, Shenzhen, China.

The declaration also took into account the vast social and political gulf between the PRC and Hong Kong. The PRC had taken drastic action to reform its economy with spectacular results. Politically, however, the PRC’s transformation was less dramatic.

To bridge the social and political divide, the PRC created the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, granting Hong Kong a degree of autonomy in all affairs except foreign and defense policy. Invested with “independent judicial power,” Hong Kong’s laws remained largely unchanged. The political freedoms enjoyed by Hong Kong, including freedom of speech and of the press, were to be protected for no less than 50 years.

The emblem of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (SAR).

On July 1, 1997, Britain returned Hong Kong to China with great fanfare. The last of Britain’s colonies in Asia was now gone. Many celebrated reunification with China while others lamented Hong Kong’s future. As the British flag was lowered and the Chinese flag rose over the city, people around the world wondered if the PRC would uphold its end of the bargain.

Troubles Since Reunification

Many shed tears of joy as Hong Kong was returned to China, but controversy began almost immediately on the night of the handover when the PRC swore in unelected officials to Hong Kong’s new provisional legislature. Pro-democracy activists took to the streets in support of Hong Kong’s democratic freedoms, which they suspected might come under threat.

For many in Hong Kong, the transition spelled uncertainty, yet for the first few years, business went on as usual.

The official ceremony transferring Hong Kong to the PRC in 1997.

Cracks began to show in the early 2000s, however. China agreed to respect Hong Kong’s laws, but differences in interpretation existed. There was also the issue of the pressure that Beijing could wield over Hong Kong’s leaders.

In 2002, the practitioners of a controversial religious sect known as Falun Gong, which the Chinese Communist Party banned in China, were arrested while protesting in Hong Kong. At the behest of Beijing, Hong Kong’s Chief Executive, Tung Chee-hwa, introduced an anti-sedition bill with provisions that would allow the government to ban organizations prohibited on the mainland.

Hundreds of thousands of people protested the measure. These demonstrations came amid growing concerns about democracy in Hong Kong following changes Tung made to Hong Kong’s political system and the government’s slow response to the SARS epidemic. Tung’s moves squeezed out pro-democracy parties, but as Hong Kong’s economy began to gain steam in the mid-2000s, concerns about democracy in the city cooled. That was, until 2014.

Toward the end of the 2000s, Beijing slowly began to assert greater control. Hong Kong was moving toward direct elections to select its Chief Executive, but in 2014, Beijing announced that it reserved the right to approve the candidates. The decision sparked a movement for transparent elections.

Protesters overlooking the crowd in November 2014 (top). Police dispersing demonstrators with tear gas in October 2014 (bottom). Thousands gathered on the thirty-first day of protest in October 2014 (right).

The resulting Umbrella Movement gained its name after protesters used open umbrellas to defend themselves from pepper spray deployed by police. Hundreds of thousands flooded into the streets and occupied parts of Hong Kong, including the Admiralty district (on the island) and Tsim Sha Tsui (a popular shopping and nightlife area in Kowloon). After nearly three months of protests, student activists such as Joshua Wong, Nathan Law, and others faced months in jail and the movement cooled.

Since 2014, Hong Kong’s government has moved forward with the construction of a high-speed railway and the world’s longest oversea bridge. Both projects link Hong Kong to China and have received mixed support by locals. Hong Kong merchants who sold books banned in China have disappeared. The PRC has initiated patriotic education campaigns aimed at transforming education curriculums in the city to foster a particular Chinese identity. All of these maneuvers, though not without support from pro-Beijing citizens, have had a chilling effect.

A map depicting the route of the Guangzhou-Shenzhen-Hong Kong Express Rail Link (left). The 55-kilometer Macau Bridge connects the cities of Hong Kong, Macau, and Zhuhai (right).

The current protests over the extradition bill are yet another demonstration against Beijing’s moves to fully incorporate the city into greater China and another sign that Hong Kong’s drive toward greater democratic control never fully stalled. Beijing may feel that Hong Kong’s continued independence further distances it from China, which might create a more difficult challenge in 2047. Beijing may also think that its moves do not jeopardize Hong Kong’s status.

Either way, China’s leaders are in a rush to incorporate Hong Kong into the future it is constructing for itself. However, the “old” Hong Kong has refused to go quietly into the night. The one country, two systems arrangement may prove inadequate if Hong Kongers refuse to relinquish aspects of their old identity and dreams of a more democratic future.

Police throwing tear gas at protesters in July 2019.

With only 28 years left before full reunification, how the two parties will bridge the gulf created by over 150 years of separation remains unclear.

Read and Listen more on Hong Kong, China, and East Asia: Hong Kong; Remembering Tiananmen; The United States and China; The China Dream; The Greening of China?; Nuclear China and North Korea; North Korea; The Myth of a Hermit Kingdom; China and Africa; Japanese Nuclear Power; Hiroshima; Taiwan’s Politics; and The Chinese Cultural Revolution.

Carroll, John M. A Concise History of Hong Kong. Critical Issues in History. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007.

Flowerdew, John. The Final Years of British Hong Kong: The Discourse of Colonial Withdrawal. New York, N.Y.: St. Martin's Press, 1998.

Hayes, James. The Great Difference: Hong Kong's New Territories and Its People, 1898-2004. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006.

Munn, Christopher. Anglo-China: Chinese People and British Rule in Hong Kong, 1841-1880. Richmond: Curzon, 2001.

Platt, Stephen R. Autumn in the Heavenly Kingdom: China, the West, and the Epic Story of the Taiping Civil War. 1st ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2012.

--- Imperial Twilight: The Opium War and the End of China's Last Golden Age. First ed. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2018.

Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang. A Modern History of Hong Kong. London: I.B. Tauris, 2004.

Vogel, Ezra F. Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China. First Harvard University Press Paperback ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013.