More than just peace and love, 1968 was a global clash against political and business establishments, which resorted to violent repression. Its legacy remains inconclusive today.

For Americans, 1968 was arguably the most traumatic year of the second half of the 20th century. Two assassinations, a failing and divisive war, and a political system that seemed unable to respond to the crises of the day. But 1968 was truly a global phenomenon, which saw unrest from Prague to Paris, Tokyo, Moscow, and Rome, to name a few. To mark the 50th anniversary of 1968, David Steigerwald, Elena Albarran, and John Davidson take us to the United States, Mexico, and Germany to examine the events of that year and the long shadow they still cast.

Is it Still 1968? Musings on a Frozen History

Given the number of half-century retrospectives I’ve read about it, 1968 was quite a year.

Writers have compared it to the most dramatic moments in modern history— 1789, 1848, 1914, 1989. In the United States, the turmoil of ’68 probably compares to 1861 and 1919.

There was an A-list of nearly monthly events, from the Tet Offensive for January and February to the triumph of Richard Nixon in November’s presidential election. Between these came the abdication of Lyndon Johnson and not one but two major assassinations. Martin Luther King, Jr. was murdered in early April, and Robert Kennedy was killed in June, almost two months to the day after King.

U.S. Marines in the ancient imperial capital of Vietnam, Huế, during the Tet Offensive (left). Richard Nixon giving his “victory” sign at a 1968 campaign rally in Pennsylvania (right).

A string of urban rebellions erupted after King’s death; Kennedy’s brought almost stunned silence as a mourning train delivered his casket from New York to Washington. Columbia University came under siege in late April and early May. In August, the Democratic Party melted down in Chicago. Then came Nixon, who implausibly offered to “bring us together.”

That’s just the A-list. The B-list included the passage of the Fair Housing Act, the third important civil-rights measure of the Sixties, the publication of the Kerner Commission report on urban disorders, and Black Power protests on the Olympic medal stand in Mexico City.

A 1964 protest against housing discrimination in Seattle, Washington (left). President Lyndon Johnson with members of the Kerner Commission in 1967 (right).

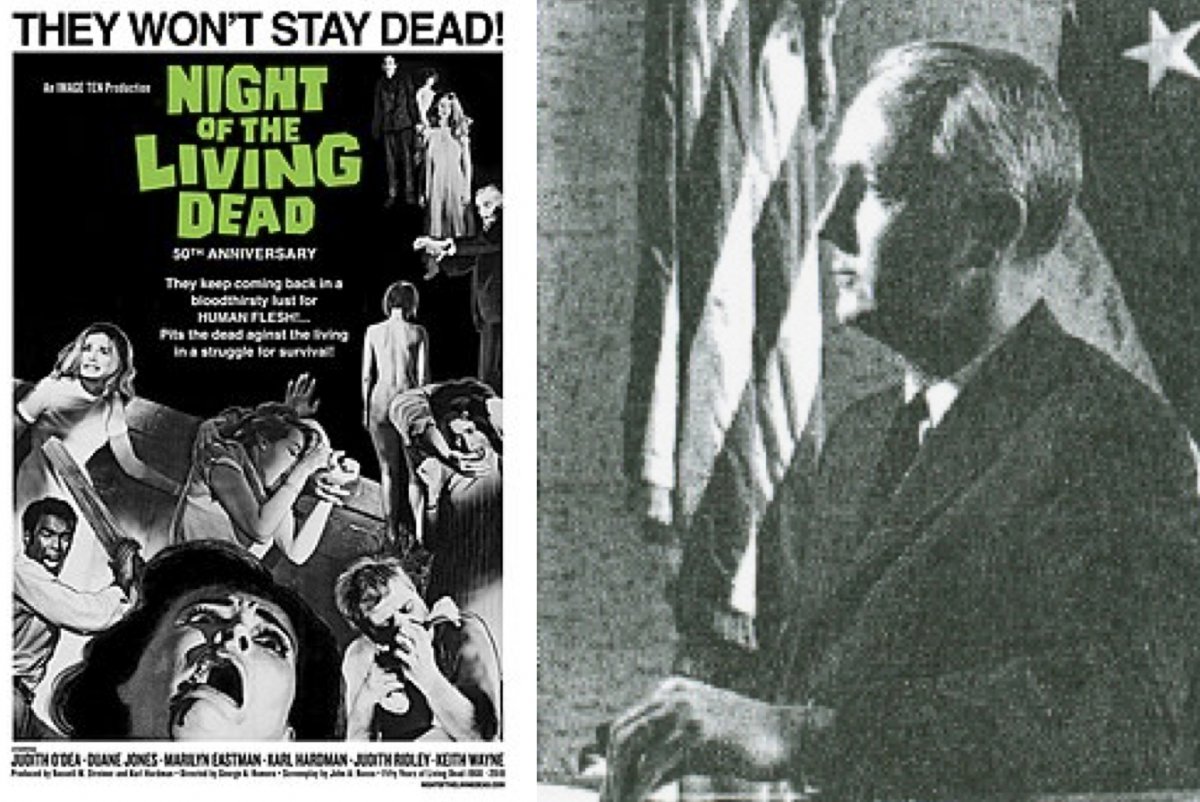

With its pictorial retrospective, USA Today reminded me that a number of things could make up C- and D-lists. The Fifth Dimension won a Grammy for “Up, Up, and Away.” The Big Mac was introduced to a then-svelte public. “Hair” premiered, as did “Night of the Living Dead,” which could probably rise to a B-list if treated as an allegory for the times—surely more suitable for it than for “Hair.”

Denny McClain won 31 games for the Detroit Tigers, which only Detroiters would rate as historically important, though he remains major league baseball’s last 30-game winner.

The theatrical poster for the Night of the Living Dead (left). John Gordon Mein, the American ambassador to Guatemala (right).

Some events seem as though they ought to be memorable but don’t show up on anyone’s lists. Who remembers the assassination of John Gordon Mein, the American ambassador to Guatemala, in August, on the very day the Democrats imploded in Chicago?

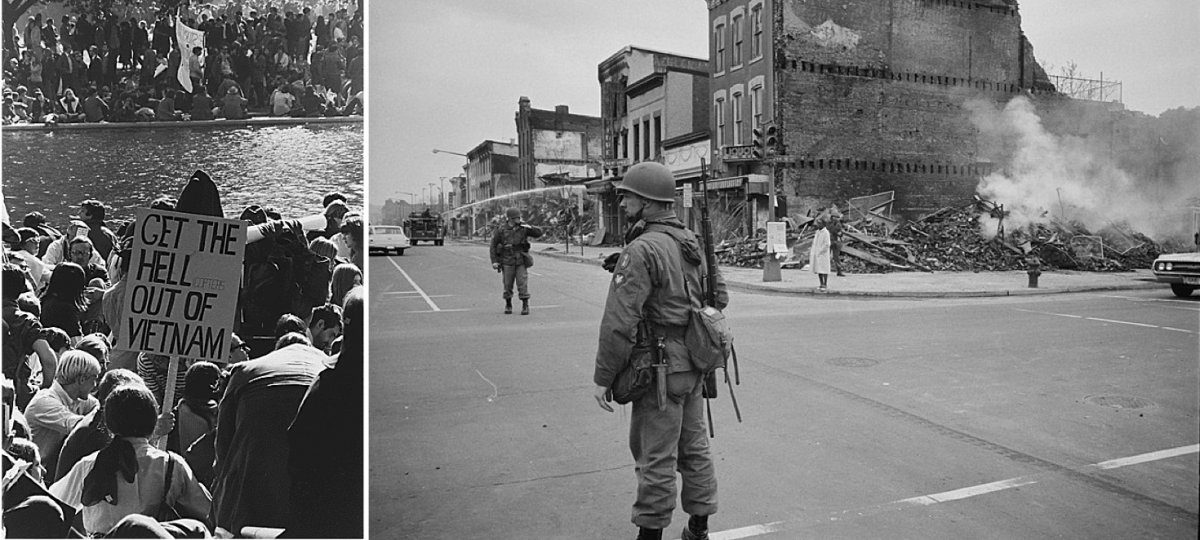

The sheer number of convulsive “happenings,” to misuse a word from the day, suggests that the undercurrents driving events were wide and deep. They were also varied. The Vietnam War and the nation’s racial nightmare stand out as the most obvious underlying causes of tumult, but they were coincidental, not interrelated.

A 1967 protest against the Vietnam War in Washington, D.C. (left). A soldier standing guard in Washington, D.C. after riots following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. in April 1968 (right).

The urban crisis, which itself developed from several different mid-century developments, also was causal, and while it was indisputably connected to the racial crisis, those two forces also were independent of each other.

At the time, many Americans believed that the “generation gap” was triggering campus uprisings, antiwar agitation, and urban riots. Social scientists diagnosed America’s social and cultural ills as evidence of an epidemic of alienation.

So maybe the way to understand 1968 is simply to note that many powerful forces came together at the same time and leave it at that.

There are ways, nonetheless, to try to apprehend the entire picture, though doing so necessarily depends on one’s willingness to work in broad strokes.

Carole Fink and her colleagues argued in the 1998 book A World Transformed that the upheaval was a protest against the Cold War order. There is much to this view, particularly when we think globally, as the authors were doing. Whether a regime was tied to the U.S. or the USSR, the “establishments” in those nations that played host to protests shared many qualities.

They were rationalized, bureaucratized warfare states. Visionless hacks and ideological automatons ran them. Because those establishment bosses mostly had come of age during World War II, generational conflict ran through the rebellions everywhere as outdated “isms” lost their credibility among the children of the postwar. From Poland to Berkeley, people were fed up with stifling systems, particularly those who had gotten a taste of consumer affluence.

If the first virtue of this explanation is its breadth, its greatest liability is in positing 1968 as an epic fight between the forces of order and the forces of change. I admit to using this language when I teach the period because it is handy, illustrative, and seductive. It also works as a way of describing the camps that flesh-and-blood people very often aligned themselves with.

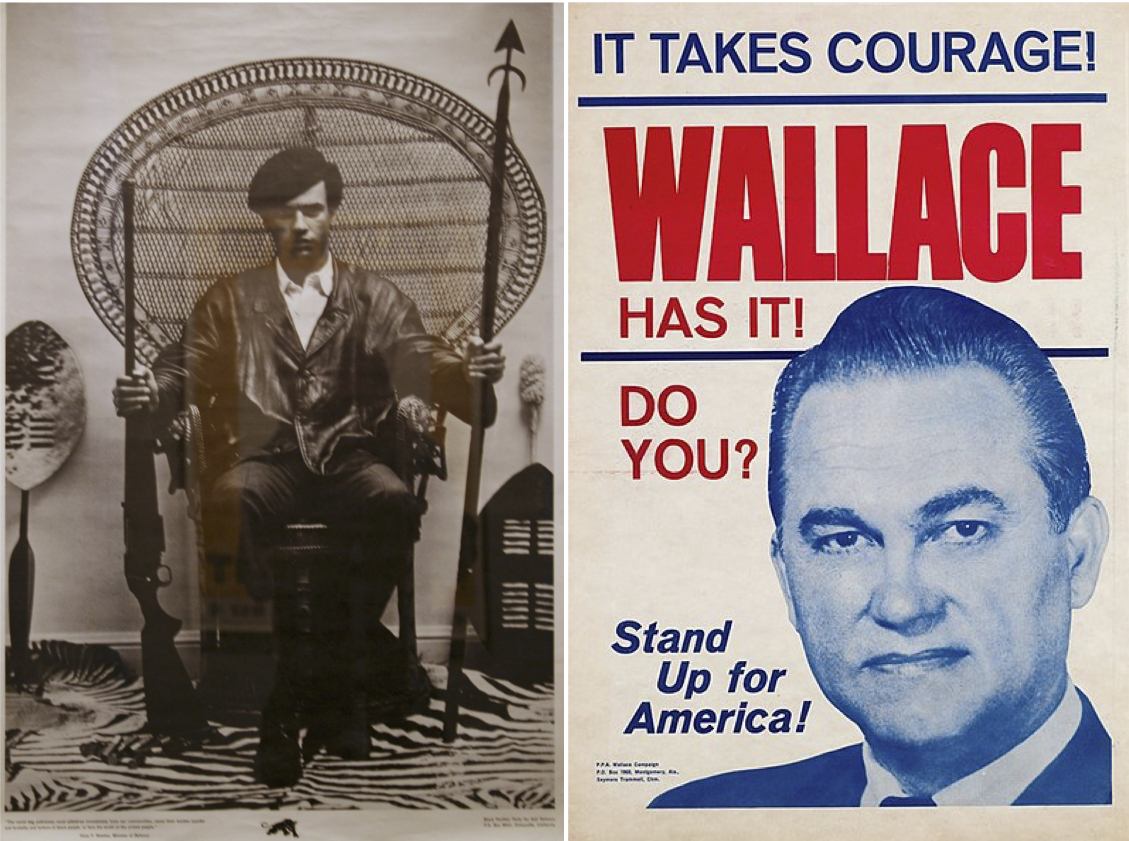

Huey P. Newton, the Black Panther Party for Self Defense’s Minister of Defense in 1967 (left). A 1968 campaign poster for George Wallace’s presidential campaign (right).

Huey Newton certainly believed that he was an agent of change, and George Wallace was self-consciously a demagogue for the forces of order. In 1970 when Ben Wattenberg and Richard Scammon defined the “average” voter as a 47-year-old housewife of a factory worker in Dayton, Ohio, they put her firmly among the forces of order.

A useful descriptor, the dichotomy hovers near the simplistic as historical explanation. It invites the presumption that one side was good and the other bad. Dubious in any case, that sort of binary is in the eye of the beholder: what was good for one person was often bad for another. That Dayton housewife feared change, not because the established order favored her so much as she feared what disorder would do to her already fragile life.

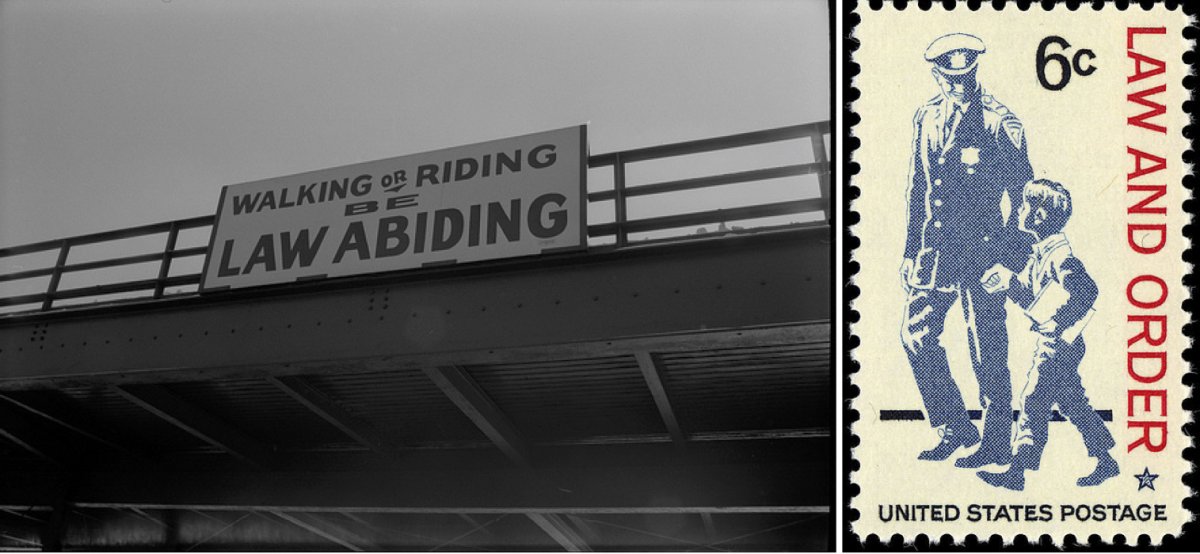

A Chicago sign as part of Mayor Richard J. Daley’s campaign for a cleaner Chicago in 1968 (left). A U.S. stamp issued in 1968 (right).

The order vs. change binary can’t even explain one of the year’s greatest Freudian slips, when Chicago Mayor Richard Daley defended his police at an August 30 press conference: “Gentlemen, get this straight, once and for all: The policeman isn’t there to create disorder. The policeman is there to preserve disorder.” Daley, apparently, had a camp of his own.

The formulation, moreover, doesn’t explain the momentum of demands for change nor account for the durability of the establishment order. With the great exception of African American activism, the forces of change in the United States were products of the technologically driven consumerism we associate with post-industrialism.

Demonstrators marching on behalf of the Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C. in 1968.

The economic processes of postwar affluence dissolved much of the foundation beneath classic bourgeois society and in the process opened up important terrain for the development of new forms of family life, sexual expression, and creative cultural forms. A new subjectivity was settling in by 1968, by which individuals could make important freedom claims against prevailing social institutions.

While obviously the momentum of change gave plenty of inspiration to those demanding an end to the war and denouncing racism, most of this post-industrial emancipation was taken in the realms of society and culture. By contrast, the structures of power in state and economy lay outside those pressures, and to the considerable extent that they continued to hold office and support wealth, the forces of order could command those structures.

A button for the Youth International Party, a radical, youth-oriented, countercultural offshoot of the free speech and anti-war movements of the 1960s (left). A 1968 anti-war march in Chicago ahead of the Democratic National Convention (right).

How individuals accommodated themselves to a world of constant change and constant stasis varies as much as do individuals. Counterintuitive though it sounds, I suggest that Richard Nixon was a crystalline reflection of the state of America, circa 1968.

As the presidential tapes make abundantly clear, Nixon was an agglomeration of mainstream bigotries, which he often folded into rants against the forces of change that lumped together the “long hairs,” “the blacks,” the “homosexuals,” the “hippies.” They weren’t just co-conspirators; they were parts of the same animal by his lights.

Yet in the midst of the 1968 election, Nixon, the least-cool man in America, appeared in a cameo on “Laugh-In,” the comedy-variety show that in ripping off hippy imagery showed the inroads of cultural change in mainstream America. “Sock It to Me?” he said, repeating one of the show’s standard jokes.

Richard Nixon’s 1968 cameo on Laugh-In.

In his obliviousness, Nixon showed that post-industrial cultural change had seeped well beyond Greenwich Village, but the structures of power—wealth accumulation, state control, the military—remained in place, even after the good buffeting that a year of turmoil brought.

This has been a recipe for stalemate, and to a large extent, the United States remains frozen in those binaries. That is the legacy of 1968.

M

exico and the Memory of 1968

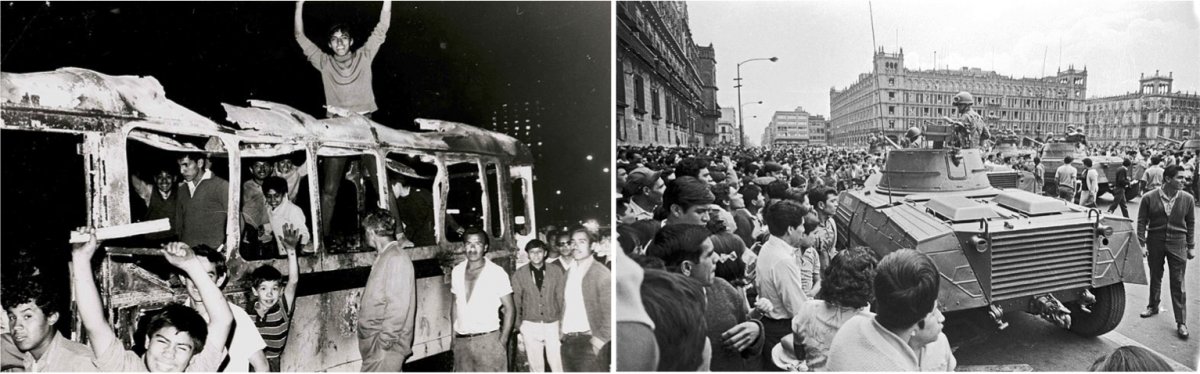

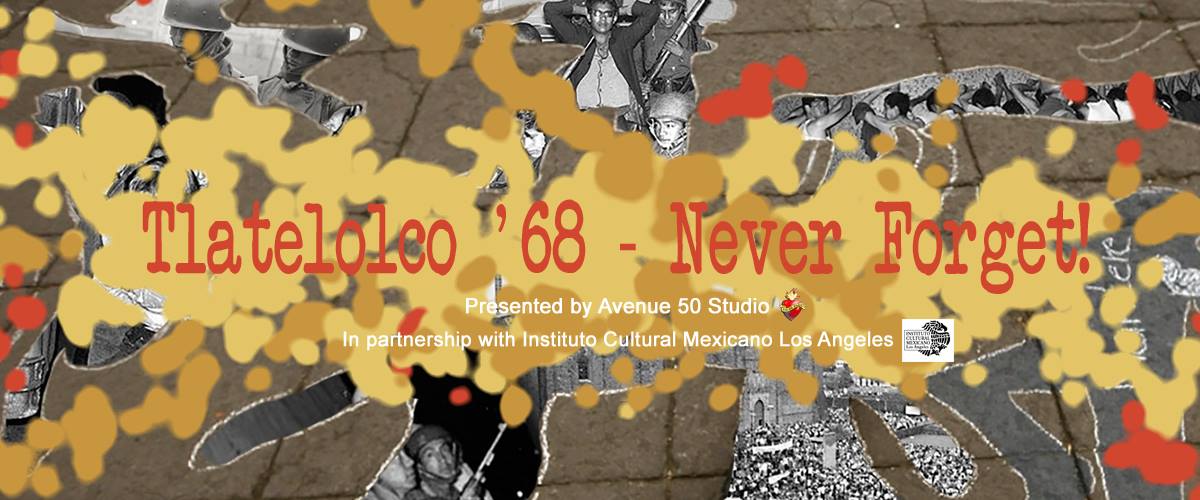

Bullets ricocheted across the Tlatelolco neighborhood Plaza of the Three Cultures in Mexico City on the evening of October 2, 1968.

They struck hundreds of civilian protestors, the vast majority college and high-school-aged activists who had gathered that afternoon in the working-class barrio to express their mounting discontent with the government. Eyewitnesses and later photographic evidence testified to the volcanic stone and concrete plaza awash with blood and to the bodies stacked in adjacent building hallways.

But on the morning of October 3, national newspapers reported only a skirmish provoked by disgruntled students. According to the official story, the demonstration was a ploy to sabotage the upcoming XIX Olympic Games, hosted for the first time by a developing country.

Just ten days later and 20 kilometers away, with civil order restored, sprinter Norma Enriqueta Basilio lit the Olympic cauldron—the first woman to do so—against the backdrop of thousands of doves (pigeons, actually).

Norma Enriqueta Basilio running to light the Olympic cauldron.

That image of peace, broadcast around the world, seemed particularly charged given the political climate of 1968. In Mexico, Olympic fever and globally inspired student mobilization converged in a maelstrom of mutual antagonism, opening a permanent fissure in the social contract between the official party (the Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or PRI) and Mexican citizens.

The student movement did not occur in a vacuum, nor was it a spontaneous uprising. Historians have demonstrated the long-term politicization of high school and college students dating back to the 1950s. Young people forged alliances with the labor sector’s National Strike Committee to try to hold their government accountable for the revolutionary promises that kept the PRI in power.

Soldiers on a street near a central plaza in Mexico City in September 1968.

Prior to the massacre, the 1968 student organizing committee had released a list of six demands directed to President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz: the release of political prisoners, reduction of the Olympic budget, elimination of the especially punitive Penal Code, compensation for police brutality, firing the abusive police chief, and the disbanding of the Granaderos (riot police).

They wanted transparency; they wanted mass media participation; they demanded that negotiations be broadcast on radio and television. (The negotiations never happened.)

A hand painted version of the logo for the 1968 Summer Olympics.

Despite the fact that Mexico’s student movement had been a serious enterprise seeking legitimate political goals for more than a decade, the image of youth as destabilizing agents framed the political narratives of 1968.

The Olympics offered an opportunity to change the image of young people. One television announcer proclaimed at the opening ceremonies: “This is the beautiful capital of Mexico. Mexico, very old and today especially very young, plays host to the cream of the world’s athletes.”

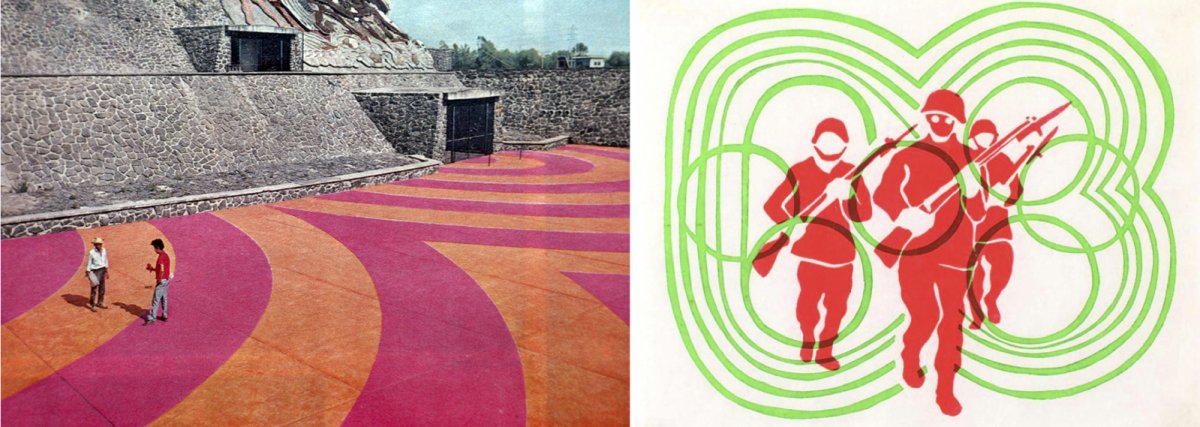

Close up on the detail of the main Olympic Stadium for the 1968 games (left). A student protester poster referencing the logo design of the 1968 Olympics and military oppression (right).

Young bodies at their most appealing and promising were on display at every turn. Pixie-cut teen models bedecked in miniskirts printed with the psychedelic ’68 logotype sashayed around the ruins of pre-Aztec pyramid structures as part of the Olympic committee’s local publicity campaign. Meanwhile, hundreds of non-conformist young bodies culled from Tlatelolco’s bloodied plaza languished unseen in the nearby Lecumberri penitentiary.

But once the world’s athletes and the international press hordes had left, Mexicans had to confront the realities of the onset of its Dirty War. Many historians consider the event that came to be known as the “massacre at Tlatelolco” the beginning of the end for the PRI, which had claimed uncontested control as the nation’s ruling party since 1929.

A meeting of graduate students in August 1968 (top left). Students protesting in September 1968 with one student’s sign reading: Everything is possible in peace (top right). Students demonstrating in August 1968 (bottom left). A teacher speaking with soldiers as students demonstrate in the background in July 1968 (bottom right).

Undeniably, the government had betrayed the public’s confidence by opening fire on its own citizens even as the PRI continued to downplay or deny the scale of civilian fatalities at Tlatelolco. After 1968, the party’s legitimacy deteriorated until the PRI lost its first election in 2000, and briefly recovered only to succumb to what contemporaries deem the final death knell in the 2018 elections.

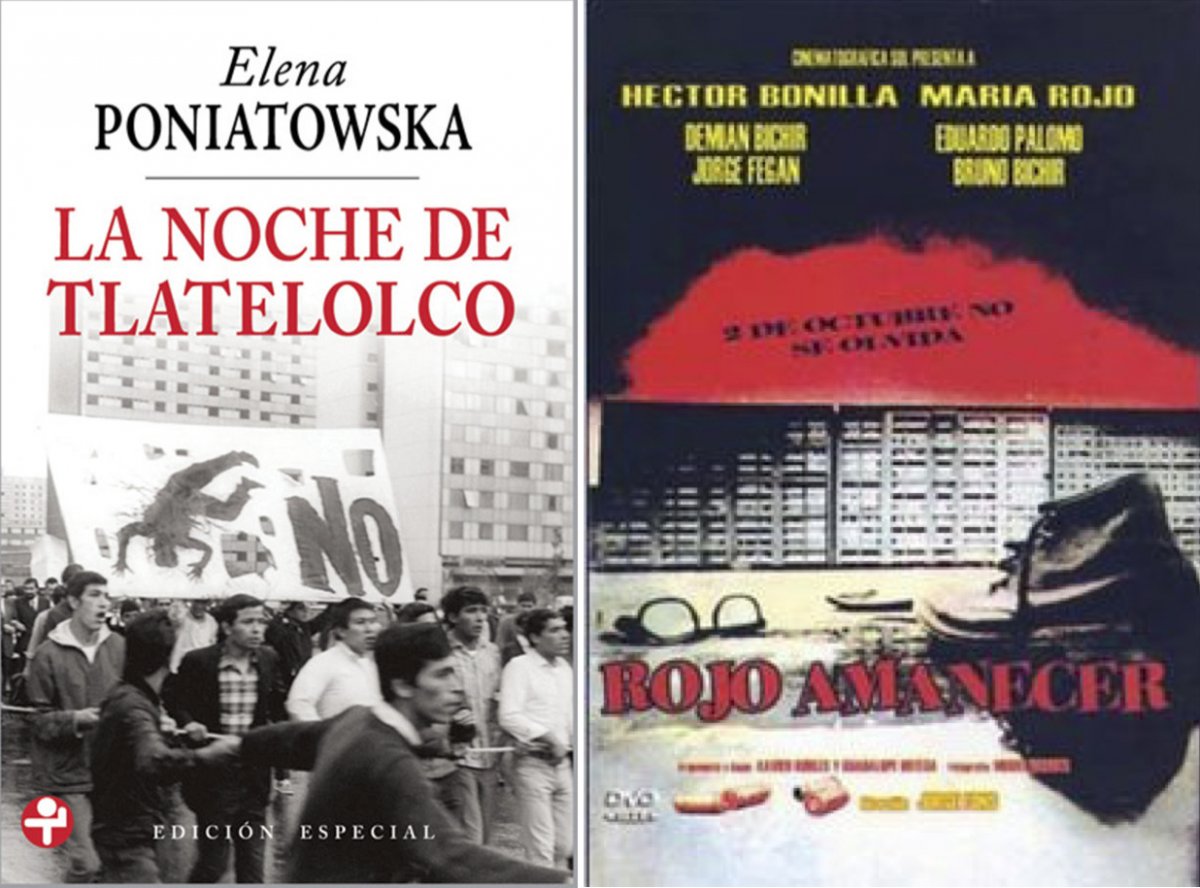

Since the massacre, there has been a vigorous struggle over how the events of 1968 are remembered. In 1975 writer Elena Poniatowska published La Noche de Tlatelolco, a collection of oral history testimonies from students, parents, government officials, police officers, union organizers, bystanders, and other witnesses to the massacre. The book’s availability in translation as Massacre in Mexico(1991) renewed global interest in the subject of state-sanctioned violence perpetrated in Mexico.

Student protesters’ adaptation of the Olympic logo with a knife through a dove.

The plot of the 1988 feature film Rojo Amanecer (Red Dawn) unfolds on the evening of October 2 in a Tlatelolco family apartment overlooking the plaza. Their intimate space is invaded by brutal riot squad violence that strips the family of their innocence, with faith in the government being the ultimate casualty. Government censors drove Rojo Amanecerunderground, where a vigorous pirating network facilitated its widespread distribution. The film was finally released in 1990.

Survivors and human rights advocates cobbled together a Truth Commission in 1993 to try to determine the number of dead, a task made difficult by the corruption and cover-up that took place in 1968. A monument erected in the Plaza of the Three Cultures in 1993 bears the inscription of the names of the officially recognized victims, and serves as the terminus for the annual commemorative march through the city every October 2. That number stands at 40, though many people believe the total number killed to be 300 or more.

Student protesters on a burned-out bus in July 1968 (left). A tank and soldiers meeting student protesters on the Plaza de la Constitución in August 1968 (right).

Efforts toward meaningful reconciliation materialized in 2007 with the inauguration of the Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco (CCUT), a multipurpose interactive cultural space that houses the official documentary and oral history archives and serves as a living memorial to the 1968 student movement. The center publishes curriculum guides for educators from elementary to college levels and encourages field trips to the cultural center.

Fifty years later, the events of October 2, 1968 continue to pull on the imagination of Mexicans.

Elena Poniatowska’s 1975 work, La Noche de Tlatelolco (left). The 1988 film Rojo Amanecer (right).

The tragicomic drama Tlatelolco: Verano del 68 (2013) depicts a cross-class love affair between students caught up the heady political climate in the summer of 1968. The icon designating the Tlatelolco stop on the city’s expansive metro system is taken and altered on the massacre’s anniversary to depict a bloody handprint. It is a wordless symbol that nevertheless conveys the memory of state oppression to the millions of passengers that pass through.

In September 2018, the CCUT will release to the public the “Colección M68: Ciudadanías en movimiento” initiative, a major archival project touted as the “digital brain of 1968” that will bring together testimonies, documents, and interactive Google maps into a free, open-access digital platform. Similarly, the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) has made available online a massive collection of primary documents from the student movement.

A memorial to the Tlateloco Massacre in Plaza of the Three Cultures.

In Mexico’s 50th anniversary of 1968, the memory of the student movement has been brought into the service of the current political climate.

The controversial populist politician Andrés Manuel López Obrador won his third bid for the presidency in July 2018, and will take office in December with his newly formed party MORENA in a victory that jettisoned the heavy mantle of the PRI.

A poster for the “50 Years, Tlatelolco, and ‘68 in 2018” conference.

In a keynote address inaugurating the conference “50 Years, Tlatelolco, and ‘68 in 2018,” conspicuously held in the Casa Elena Poniatowska, former UNAM rector Juan Ramón de la Fuente proclaimed that López Obrador’s victory would not have been possible if not for the path for pluralistic democracy opened by the student activists and martyrs of 1968. Though such political statements draw perhaps too tidy a chronology, clearly the legacy of 1968 still resonates.

T

he Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), 1968: Fighting (for) the People

In May 1968, nearly 100,000 West German students and workers marched in the capital city of Bonn against an emergency law being debated in Parliament. It was the climax of the protest movement of 1968, a campaign against deceptive and repressive practices of the political status quo.

To understand that moment in Bonn, we need to look back at the political and social tensions that had been building since the late 1950s. At the core of the upheaval was a fierce debate over how to define the German “people” and shifts in the meaning and attribution of the loaded term “enemy of the people.”

Student protesters at the Berlin Institute of Technology in May 1968.

The story of “FRG 1968” really took off with the Spiegel Affair of 1962. Der Spiegel,a Hamburg-based weekly news magazine, published a cover story on the inadequacy of the Federal Republic of Germany’s (FRG) armed forces in relation to those of the Warsaw Pact members. Informed by inside sources, the article and was particularly critical of Defense Minister Franz Josef Strauss.

Cries of “treason” from the highest levels of government led to the occupation and search of the Spiegel offices, the arrest of the chief editor, and the interrogation of journalists. No evidence to support criminal charges emerged.

The public reacted with spontaneous and broad-based outrage at this attempt to censor the free press. Observers across the spectrum heard echoes of Nazi jack-boots stomping across the FRG. West Germany’s postwar “Economic Miracle”—which had brought the country from wartime devastation to robust economic growth and development in a matter of a decade—had made it easy for citizens to gloss over their memories of the Nazi years.

The Spiegel outcry doubled when Strauss worked with the Franco dictatorship to arrest the article’s author while he was on vacation in Spain. Eventually, the public’s insistence on freedom of the press and on restricting the arbitrary use of state power triumphed over the claim that criticizing a high-ranking government official made journalists “enemies of the people.”

The Spiegel Affair not only chased Strauss out of the Cabinet but led to the retirement of Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, the widely respected “Old Man” of FRG politics, a year later. It also started West Germany on the road to 1968 by weakening the iron grip that the Christian-Democratic Union (CDU) had held on the government.

Federal Chancellor Konrad Adenauer in 1965.

During Kurt Kiesinger’s tenure as German Chancellor (1966-1969), his CDU party lost sufficient public support that it found it necessary to devise a “Grand Coalition” with its rival, the Social Democratic Party (SPD). Kiesinger’s Nazi past fueled opposition and worry that the CDU was a tool to reassert authoritarian government. Kiesinger had been former chief liaison to Joseph Goebbels’ Ministry of Propaganda when he worked as deputy director of the Foreign Office’s broadcasting department.

During the collaboration, the left-leaning wing of the SPD lost all hope that the CDU might be a vehicle of change. Rather the SPD followed the Socialist German Students (SDS) movement, which had for years questioned the establishment’s connections to the militaristic past and the Holocaust. They joined other students, radical unions, and a broad spectrum of intellectuals to form an Extra-Parliamentary Opposition.

A 1965 poster for the Christian-Democratic Union with Kurt Georg Kiesinger (left). The logo of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (right).

Here, terrifying memories of the Nazi past and student fears that elites connected with the CDU would bring back the oppressive practices of the radical right led to the growth of social movements in West Germany that took to the streets in 1968.

The APO sought to bring pressure upon the ruling coalition and effect social change from outside the institutions of government. They strove for public forums independent of state control and the capitalist marketplace where they could voice their alternative vision for Germany.

The first classes of the Berlin film school, established in 1966, included some of the vanguard of this “counter-public sphere” hoping to re-inform, and thus to reshape and win over, the German public (such as Harun Farocki, Holger Meins, and Helke Sander). They used their short films to critique the conservative tendencies of the West German government and the threats they saw of American imperialism and the capitalist press—labeling them “enemies of the people.”

In particular, they condemned the corporatization of the German press, which they felt was not only being muzzled by government forces (like in the Spiegelcase) but also controlled by a small contingent of wealthy media companies. The Springer Press in Berlin, which had cornered roughly 70% of the market, became one of their primary targets.

Protesters in Hamburg in 1968.

In the ever more mobilized and tense environment of the 1960s, West Berlin became a center of agitation. It became more radicalized not just because of its two universities and film school, but also because its status as an occupied city protected Germans from the FRG’s compulsory military service while there. Young men who wanted to avoid service, many of whom held strong anti-war sentiments, took up residence there and gravitated to its oppositional scene.

While the war in Vietnam was its most glaring example of U.S. imperialism, the APO rejected U.S. intervention in other places as well. In June 1967, the Shah of Iran, returned to power in 1953 by a coup backed by the United States and Great Britain in order to maintain their oil interests, and his third wife made an official state visit to West Berlin.

A 1967 state reception for the Shah of Iran in West Germany (left). Protestors in 1967 at the Schöneberg Town Hall in Berlin (right).

During the ensuing demonstrations, the police shot protester Benno Ohnesorg, a university student, who died before reaching the hospital. Photographers had crowded over him for some time before an ambulance was called, solidifying the sense that the state and press were in cahoots.

Countercultural student groups such as the Kommune 1, a politically mobilized commune in opposition to the traditional family, had previously limited themselves to symbolic actions like “pudding assassinations” and property damage. After the Ohnesorg shooting, they accepted violence as necessary in the face of the West German government’s complicity with U.S. actions in Iran and its violent suppression of public opposition.

At Ohnesorg’s funeral, student activist Rudi Dutschke advocated peaceful avenues to change but cautioned that the APO must be ready for the violence that the state was prepared to use and the conservative press helped the people accept.

An anti-communist activist shot Dutschke on April 11, 1968, leaving him with severe brain damage. Dutschke had been labeled an “enemy of the people” in the Springer tabloid Bild-Zeitung, and much of the counterculture attributed the attempt on “Red Rudi”’s life to campaigns of misinformation and character assassination. Demonstrations and clashes with police increasingly occurred at the Springer building in Berlin.

The German government exacerbated the situation in May when it considered “Emergency Acts” allowing the Cabinet to suspend parliamentary rule and enact laws in times of (perceived) crisis. This raised the specter of the Weimar Constitution’s self-cancelling statute, which had contributed significantly to the legitimation and entrenchment of the Nazis in the early 1930s. These worries brought tens of thousands of demonstrators to Bonn, but not the same broad cross-section of the populace that had reacted to the heavy-handedness of the Spiegel Affair.

The Emergency Acts passed and dealt a blow to the protest movements because the German people—manifested in the elected government—clearly resented the possibility of radicals’ incursions into their comfortable lives more than they feared the return of authoritarianism. By the end of May, the refusal of the German population to coalesce around the APO’s causes was unmistakable—diminishing the momentum of the ’68 movement in Germany.

Policemen beating a demonstrator in 1967 in Berlin.

Fault lines appeared within the APO, and the three film school students mentioned above represent the tendencies of the resulting split. Sander became a central figure in the burgeoning women’s movement that mobilized because the APO mirrored the traditional gender inequities of bourgeois society. Farocki undertook the long “march through the institutions” as a filmmaker, critical intellectual, and, eventually, teacher at the Berlin Film School.

Most radically, Meins joined the Red Army Faction (RAF, aka the Baader-Meinhof Group, a radical, belligerent left-wing organization) to take up armed resistance against a West German state he considered fascistic. Captured along with the ringleader, Andreas Baader, in 1972, he died as the result of a hunger strike protesting the conditions of the RAF’s incarceration in 1974.

Sporadic violent insurgency continued through the 1970s, but the opportunity for militants to win over the public and lead the people never materialized, partly because the state could sell its anti-democratic actions as defensive measures.

Meanwhile, the Springer Press, its sales unshakeable, relentlessly tarred all three sets of leftist as “enemies of the people.”

The Springer Press Building next to the Berlin Wall in 1977.

Nonetheless, many of the emancipatory aims of the APO came to fruition in the 1970s and have taken root in Germany’s public self-conception: curricular improvement and less-authoritarian educational methods; better conditions for students; attention to the legacies of World War II and the Holocaust; police and judicial reform; recognition of women’s rights; and support of human rights throughout the non-western world.

The contradictions of “FRG 1968” discussed here suggest that labeling a group the “enemy of the people” facilitates its immediate marginalization but may actually foster its goals long term.

Mark Kurlansky, 1968: The Year that Rocked the World, New York: Random House, Inc., 2005.

David Farber, Chicago '68, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1988.

Carole Fink, Philipp Gassert, and Detlef Junker, 1968: The World Transformed, Cambridge: The University of Cambridge, 1998.

Lewis Gould, 1968: The Election that Changed America, Chicago, Ivan R. Dee Publisher, 1993.

Richard Vinen, 1968: Radical Protest and Its Enemies, New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2018.

Norman Mailer, Miami and the Siege of Chicago, New York: New York Review of Books, 2008.

Brewster, Keith, ed. Reflections on Mexico ’68. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Sheppard, Randal. A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2016.

Poniatowska, Elena. Massacre in Mexico. Kansas City: University of Missouri Press, 1991.

Zolov, Eric. “Protest and Counterculture in the 1968 Student Movement in Mexico.” In Student Protest: The Sixties and After, ed. Gerard J. DeGroot. London: Longman, 1998. pp. 70-84.

Timoth S. Brown, “‘1968’ East and West: Divided Germany as a Case Study in Transnational History.” AHRForum. American Historical Review (February 2009) 69-96.

Rob Burns and Wilfried van der Will. Protest and Democracy in West Germany: Extra-Parliamentary Opposition and the Democratic Agenda. MacMillan Press, 1999.

Hans Kundnani, Utopia or Auschwitz?: Germany’s 1968 Generation and the Holocaust. Columbia UP, 2009.

Hanna Schissler (ed.). The Miracle Years: A Cultural History of West Germany, 1949-69. Princeton UP, 2011.