Many election cycles feel “unprecedented” in the moment. Some, however, really do represent something completely new in American political history, and not always because of what the issues were or who the victor was. The following ten elections each brought something never seen before to the American electoral process—and the effects of these innovations were long-lasting. They set subsequent political norms, permanently altered the composition of national political coalitions, or revealed structural weaknesses in the conduct of democracy itself.

1. 1800

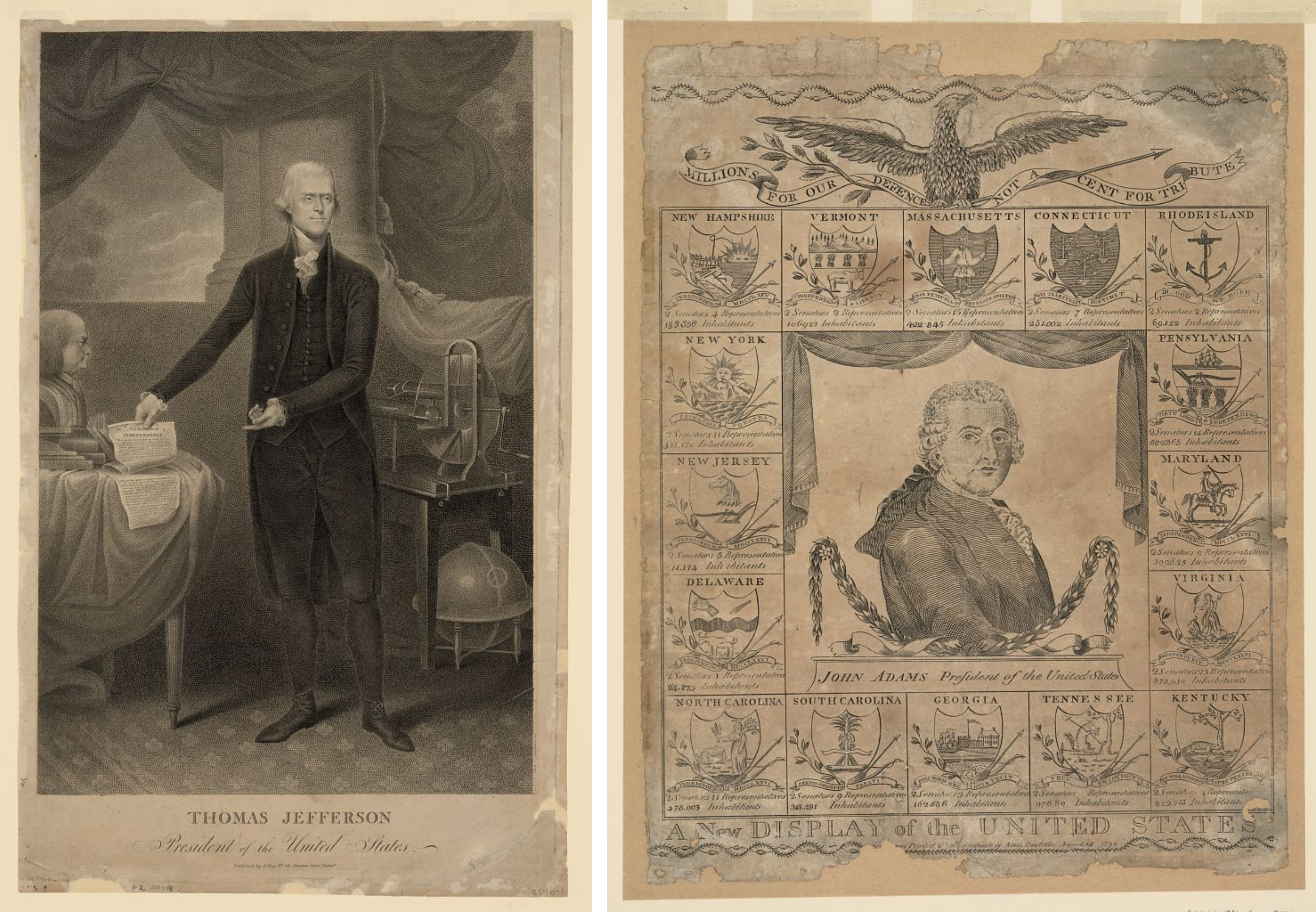

Portraits of Thomas Jefferson (left), and John Adams (right). (Source: Library of Congress Online Catalogue)

The Election of 1800 set precedent for the peaceful transition of power from a ruling to an opposition party. The election itself, however, was not smooth, due in part to the fact that the Electoral College had not been designed to accommodate party-ticket politics. Originally, electors each cast two ballots, with the winner becoming President and the runner-up Vice-President. In 1796, this had led to an administration split by party, with John Adams as president and his opponent, Thomas Jefferson, serving awkwardly as his Vice-President.

To prevent a similar occurrence in 1800, electors in both the Federalist and Republican parties agreed to vote for a party slate. After a campaign filled with personal invective and apocalyptic predictions of disaster should the other party win, the Republican slate of Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr defeated the Federalists John Adams and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, 73-65.

In order for the party slate plan to work under the existing rules for President/Vice-President, it was necessary for at least one Republican elector to vote for Jefferson but not for Burr, thereby avoiding a tie. When the ballots were opened, however, it emerged that no Republican elector had done so, and Jefferson and Burr tied at 73. The election was then thrown into the House of Representatives – and not the newly-elected House, where Republicans held a majority, but the sitting House, dominated by Federalists.

Furthermore, the rules stipulated that because Jefferson and Burr tied, but each had a majority, the House had to choose between them. After 36 ballots, Jefferson emerged the winner, due in part to backstage efforts by Alexander Hamilton to convince key Federalists that, despite their long-standing fears about Jefferson, it was Burr that represented the existential threat to the survival of the Republic. Burr took note of this view for future reference. Despite the contentious process, Jefferson assumed the Presidency without violence from the losing side.

2. 1824

Between 1804 and 1820, presidential elections fell into a stable, un-dramatic pattern. Jefferson (1800 and 1804), James Madison (1808 and 1812), and James Monroe (1816 and 1820) were all Virginians who had served as Secretary of State under the previous Virginian president. Monroe, in particular, faced very little opposition due to the collapse of the Federalist Party and a decline in national partisanship, a period sometimes referred to as “The Era of Good Feelings.”

This pattern broke down in 1824, however. Monroe’s Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams, failed to receive nomination from the Congressional party caucus system, which had determined party tickets up until that point. The result was a four-way race focused on regional favorite sons: Adams of Massachusetts, William H. Crawford of Virginia, Henry Clay of Kentucky, and Andrew Jackson of Tennessee. Jackson, the popular military hero of the Battle of New Orleans, won the most popular votes but fell short of a majority in the Electoral College, throwing the election into the House. There, supporters of Adams and Clay joined forces, electing Adams President. When Adams then appointed Clay Secretary of State – thereby positioning Clay as his chosen successor – Jackson partisans cried foul. Jackson’s 1828 campaign began almost instantaneously, and his victory in the rematch against Adams ignited a return to polarized partisanship in national politics.

3. 1844

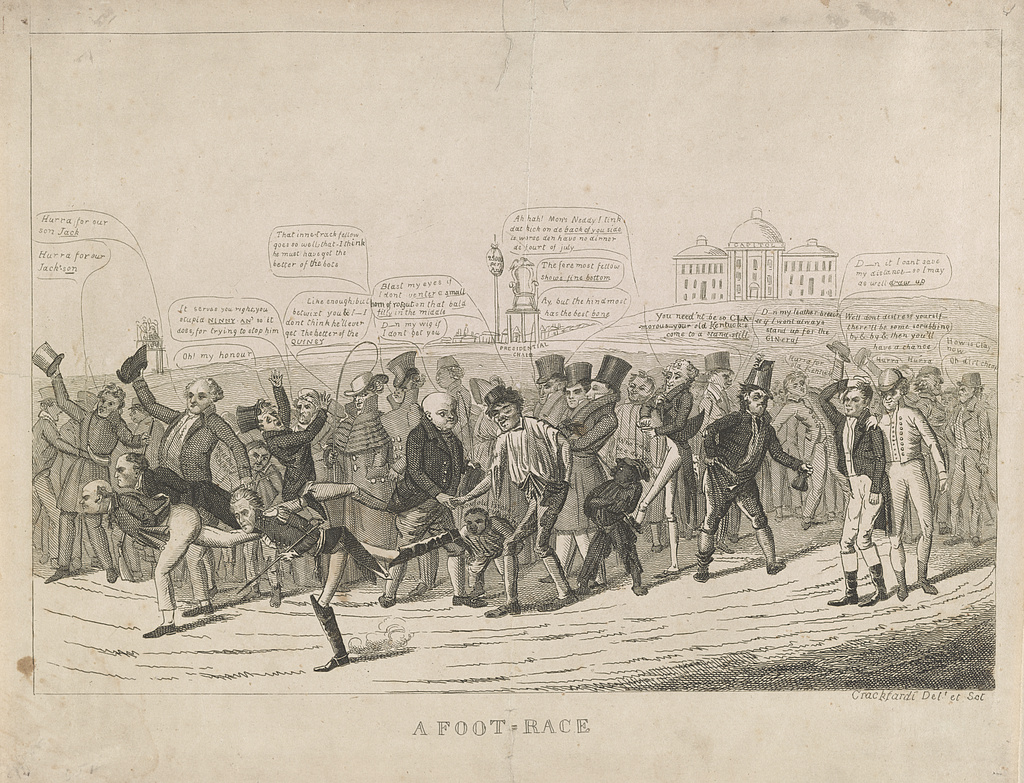

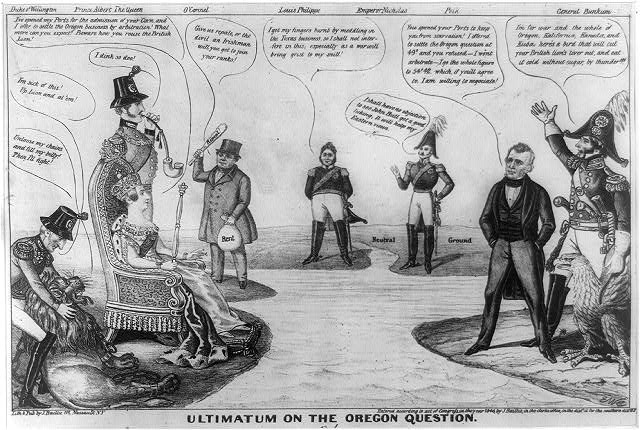

The Election of 1844 saw the first emergence of a “dark horse” candidate for President and set in motion the eventual collapse of the Second Party System. Most observers anticipated a contest between former President Martin Van Buren (D-NY) and Henry Clay (Whig-KY). Van Buren and Clay anticipated it, too; so much so that in 1842, they agreed privately to keep the issue of Texas annexation out of the campaign, as it held the potential to damage them both.

At the 1844 Democratic Convention, however, supporters of the relatively unknown Tennessee governor James Polk took the nomination away from Van Buren by promising regionally balanced belligerence: an aggressively pro-annexationist stance on Texas combined with a maximalist anti-British demand on the border between Oregon and Canada. Expansion for the slave south, expansion for the free-labor north.

Polk won the general election on a slogan of “54.40 or Fight!” He then compromised with Great Britain to extend the U.S. Canada border along the 49th parallel, triggered a war against Mexico over the border of Texas, and annexed what was then northern Mexico and is now the American southwest. These actions accelerated the regional crisis which led, in 1860, to secession and civil war.

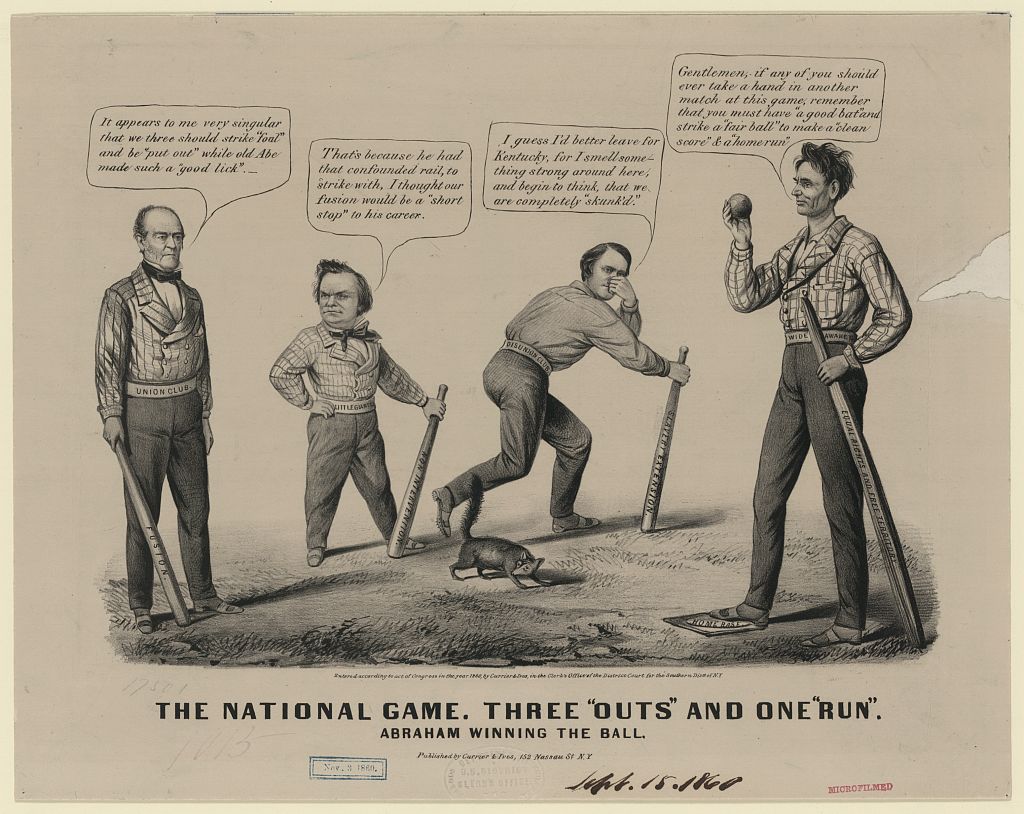

4. 1860

The election of 1860 was really two elections, not one. Democrats, unable to agree on a nominee acceptable to both free-state and slave-state delegates, split, resulting in a northern Democratic candidate, Steven Douglas of Illinois, and a southern Democratic candidate, John Breckinridge of Kentucky. Northern voters faced a choice between Douglas and Republican Abraham Lincoln, a former Whig with a short public resume but a long record of opposing the spread of slavery to western territories. Southerners chose largely between Breckinridge and John Bell, of the Constitutional Union party. Although Bell earned some votes in the lower north as well as the upper south, only Douglas made any real attempt to campaign on a national basis. When Lincoln achieved a majority of the Electoral College by winning every free state, but no slave states, it triggered a wave of secession votes in southern state legislatures, and, by the following year, the Civil War.

5. 1874

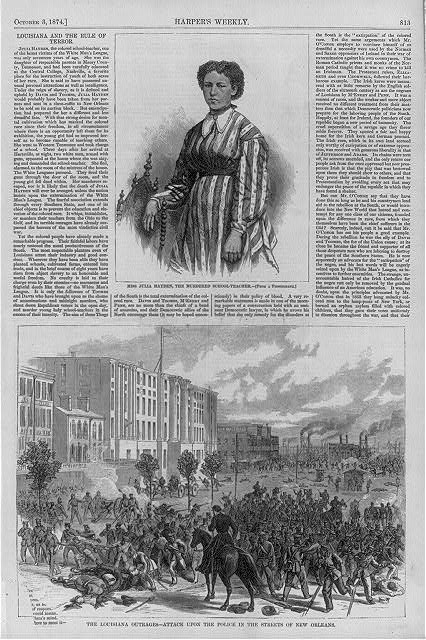

Harper's Weekly page illustrating a story on Julia Hayden, a school teacher murdered by members of the "White Man's League" in Louisiana in 1874. (Source: Library of Congress Online Catalogue)

During the Reconstruction period, state-level elections in the former Confederacy frequently devolved into terror, violence, and disorder. For most of the administration of Ulysses S Grant (1869-76), Grant and the Republican Party sought to redefine politics in the former Confederacy by protecting the political and civil rights of former slaves, as enshrined in the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the Constitution. White supremacist Southerners fought back, often literally.

In addition, both Republicans and Democrats sought to build themselves into truly national, and not just regional, political coalitions. Republicans sought to make themselves the permanent party of Union, bringing together northern supporters of the war effort with African-American voters and southern white opponents of succession, such as so-called “upcountry Unionists.” Democrats sought to rebuild their party by uniting northern and southern opponents of Federal power and Reconstruction social policy, often in explicitly racist terms, and often through direct suppression or intimidation of black voters.

The 1874 midterm elections, in which Democrats regained control of the House of Representatives for the first time since secession and succeeded in “redeeming” several southern states, represented the waxing of Democratic efforts to stymie Reconstruction and the waning of Republican efforts to defend it.

Across the South, Democrats made gains at the polls, and sometimes resorted to violence when they didn’t, as in Louisiana, where Federal troops were required to suppress an insurrection against the election of Governor William Pitt Kellogg and a Republican-controlled statehouse. In the north, Democrats made additional gains due to the Depression of 1873 and the atrophy of northern Republican appetites to continue fighting Southern political battles with Federal power. By 1876, American politics had re-balanced around two party coalitions of roughly equal national size, but strongly regional character.

6. 1876

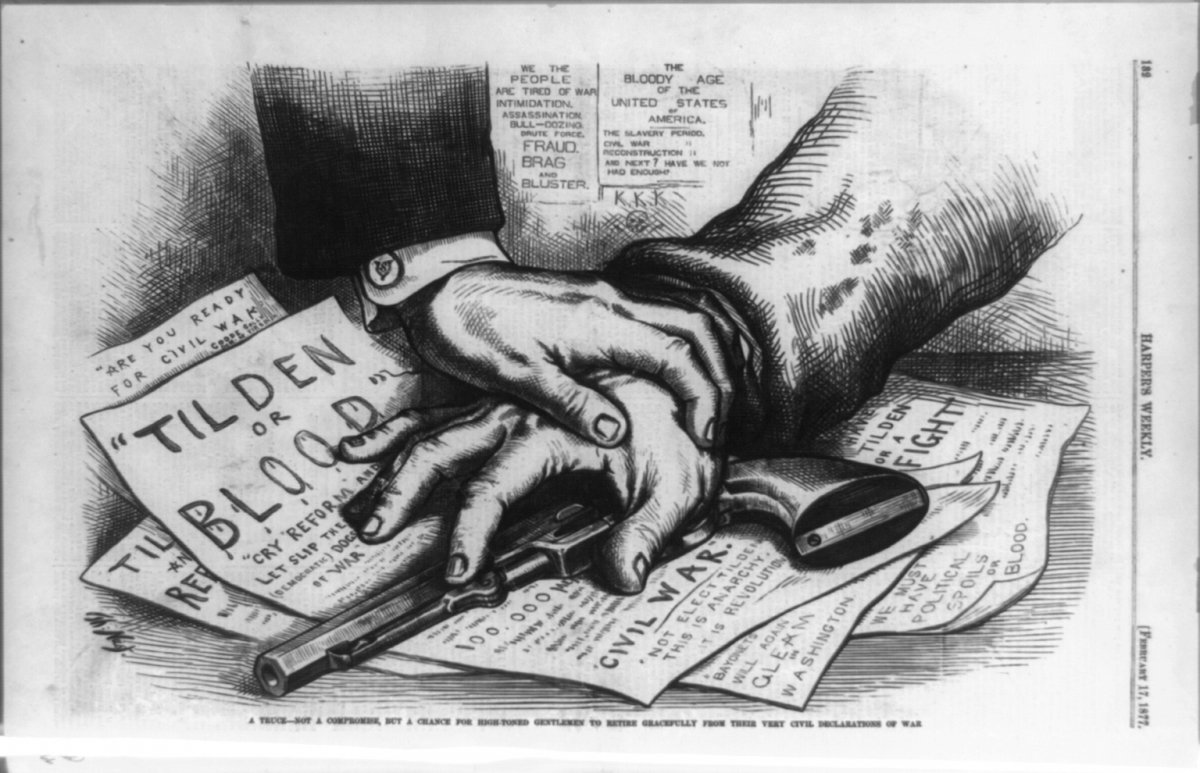

By 1876, the Democrats had recovered so completely as a national party that Samuel Tilden was able to win a popular vote majority of over 200,000 against Republican Rutherford B. Hayes. Vote totals were contested, however, in three southern states — the three still governed by Republican majorities, where Reconstruction patterns of fraud, voter suppression, and white supremacist violence continued to shape election day. An additional contested elector in Oregon left Tilden one electoral vote short of victory.

In a complex series of political deals involving a federal election commission, railroad subsidies, and the renewed threat of regional violence, Hayes was awarded every contested electoral vote in exchange for an implicit promise that his administration would remove the last Federal troops from the former Confederacy. This “Compromise of 1877” made Hayes President by one electoral vote and brought the effort to support the rights of former slaves with Federal power — Reconstruction — to an end. The press often referred to President Hayes as “Rutherfraud.”

7. 1912

The chaos of the 1912 election began in 1908, when Theodore Roosevelt bequeathed a healthy Republican majority and the mantle of progressive reform to his chosen successor, William Howard Taft. Roosevelt then went big-game hunting in Africa. By the time he returned in 1910, he had become convinced that Taft was squandering his legacy. The result was a two-year split in the Republican coalition between conservatives and progressives, culminating in Roosevelt's attempt to take the 1912 nomination away from his own chosen heir. When he failed, he launched a third-party bid under the Bull Moose banner and continued the fight into the general election. In the resulting three-way contest, Woodrow Wilson was elected president with less than 42% of the popular vote but a huge electoral majority, and Taft, the incumbent, came in third with less than a quarter of the total vote -- the worst performance by an incumbent President seeking re-election by a wide margin.

8. 1940

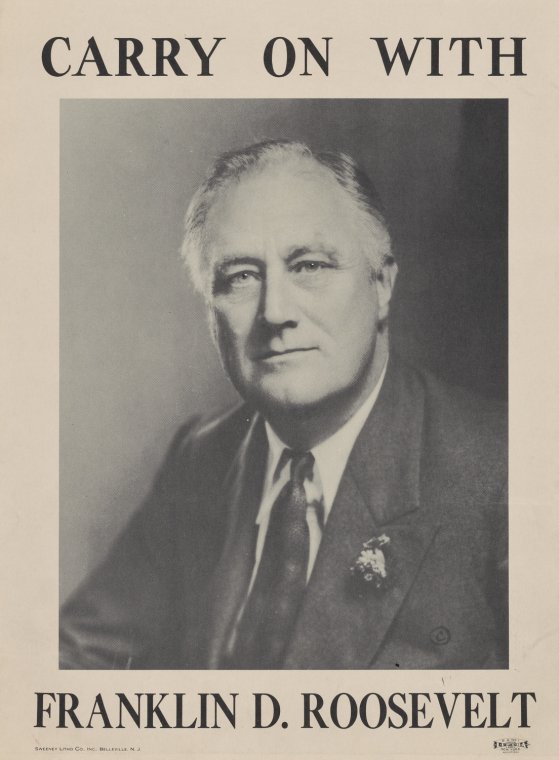

Until 1940, no President received a third bite at the apple. (There had been an effort to nominate Grant for a third term in 1880, but it fizzled on the convention floor.) The international crises in Europe and the Pacific, however, led both major parties to make unorthodox choices.

The Republicans nominated a relatively obscure utilities executive named Wendell Willkie. Willkie had no record of public service, and had been registered as a Democrat until 1939. But he had been a public opponent of the New Deal, and, more importantly, was an internationalist who advocated military aid to Great Britain. His nomination represented the effort to deny the Presidency to popular isolationist Republicans such as Robert Taft of Ohio or Thomas Dewey of New York.

Meanwhile, at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, Franklin Roosevelt was nominated for an unprecedented third term, a result engineered in part by staging a faux-spontaneous “We Want Roosevelt” boom orchestrated by pre-positioned operatives of Mayor Ed Kelly’s Chicago political machine. Roosevelt went on to win re-election not once but twice more, leading the nation until his death, shortly before VE Day, in 1945. In 1947, Congress passed the 22nd Amendment, limiting subsequent Presidents to two terms.

9. 1948

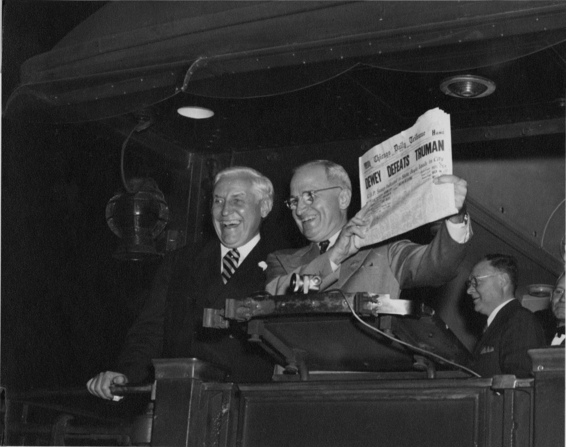

Democrats had dominated national elections since 1932, but with a coalition containing significant internal tensions—particularly between northern liberals and the conservative, segregationist “Solid South.” After WWII, as civil rights became a more prominent national issue and African-American voters in northern cities began casting votes for Democrats, this coalition sometimes became hard to maintain.

Harry Truman found this out in 1948, when southern segregationists walked out of the Democratic convention over the plank of the party platform that supported civil rights, and ran South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond as a third party candidate on an explicitly segregationist platform. To Truman’s left, a fourth party candidate, Henry Wallace, ran on a platform of opposition to the emerging Cold War between the U.S. and the Soviet Union.

Republicans therefore thought their nominee, New York governor Thomas Dewey, would cruise to victory. Opinion polls suggested the same. Truman closed the gap late with a vigorous campaign schedule, however, and secured a majority in the electoral college. Many national publications had pre-planned post-election coverage which assumed a Dewey victory; one particularly conservative news outlet, the Chicago Tribune, actually published its originally scheduled “DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN” headline in its early edition.

10. 2000

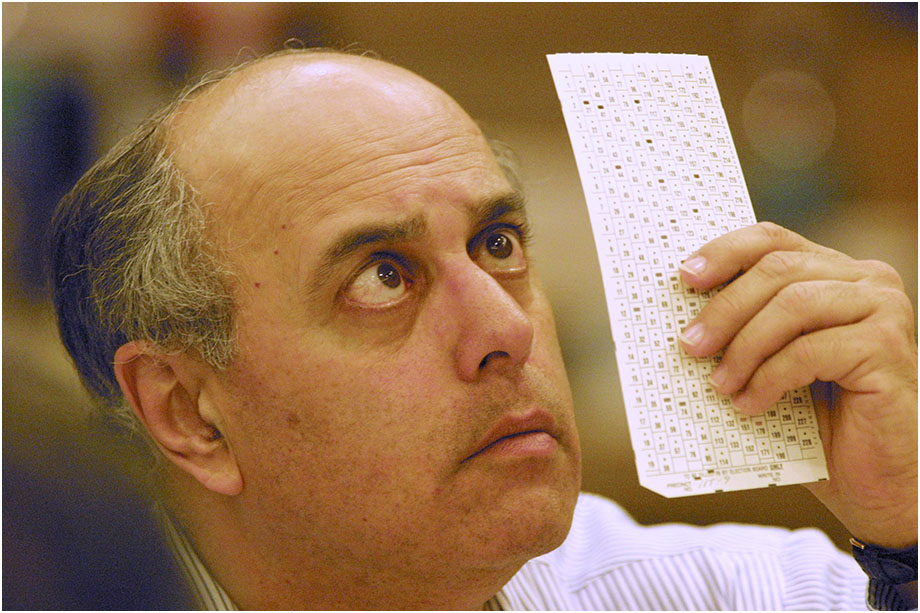

A Florida election official reviews a paper ballot during the 2000 recount.

The bulk of the 2000 campaign seemed, at the time, to be both relatively low-stakes and relatively dull. Vice-President Al Gore, Ivy-educated scion of a prominent political family, sought to capitalize on the peace and prosperity engendered by the administration he'd served in without associating himself too closely with its extracurricular foibles. Texas governor George W. Bush, Ivy-educated scion of a prominent political family, sought to re-brand post-Reagan conservatism, much as his father had.

On election night, exit polls suggested that Gore would win a close election on the strength of a victory in Florida, which news organizations called for Gore early in the evening. As raw vote totals came in, however, the networks reversed themselves, first declaring Florida "too close to call" and then, around 2:30 a.m., awarding it to Bush. Uncounted votes remained in several heavily Democratic counties, however, and once they were counted, around 4:30 am, Bush's margin of victory was within the margin requiring a mandatory recount. Gore, who had called Bush to concede earlier in the evening, called back to un-concede. Vote margins were also too close to call in Oregon and New Mexico. Americans woke up the next morning to no victor.

This resulted in a month of legal battles over the Florida vote returns, during which Gore sought recounts under conditions and circumstances likely to be favorable to his cause, and Bush—whose brother Jeb was governor of Florida at the time—sought to stop the recount and certify the original Florida vote totals. The counting process revealed a number of weaknesses in Florida balloting methods, including punch-card ballots, which sometimes produced inconclusive “undervotes,” and a confusing “butterfly ballot” in Palm Beach county, which may have caused thousands of Gore voters to accidentally cast ballots for arch-conservative Pat Buchanan.

Ultimately the recount lawsuits reached the Supreme Court, where, in Bush v. Gore, the Supreme Court ruled that Florida’s recount process was unconstitutional and that Bush’s original margin of victory—537 votes out of just under six million cast or roughly 0.009%—should be certified. Gore won the national popular vote, but lost the electoral college—a result he was constitutionally required to certify himself, in his role as sitting Vice President and presiding officer of the Senate.

Elsewhere, John Ashcroft lost his Missouri Senate seat to a dead man and Hillary Clinton became the only First Lady to achieve elective office on her own. Both eventually went on to more powerful positions.