Few democracies have more fractious politics than Israel. Often those divisions are portrayed as revolving around the Palestinian crisis, the peace process, and the Arab-Israeli conflict more broadly. This month, however, historian Ori Yehudai describes how ethnic divisions within Israel—tensions between Mizrahi Jews and Ashkenazi Jews—are in some ways the foundational fault line in Israeli politics.

During the past year, Israel has experienced an unprecedented political crisis.

The country held two rounds of elections in April and September 2019 that failed to produce a government. And now, more than two months after a third round in March 2020, Israeli politicians are still struggling to establish a government under close scrutiny of the Supreme Court and amidst growing public criticism.

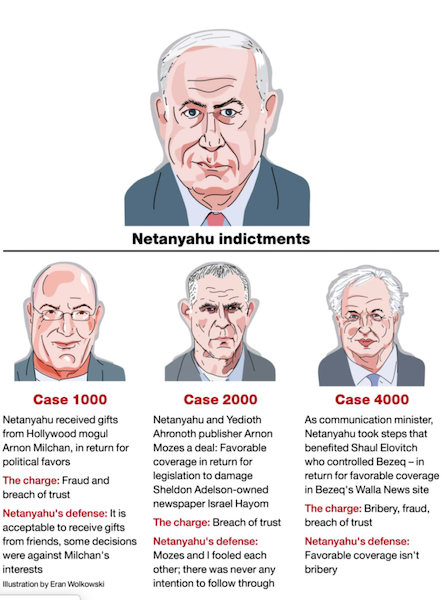

To compound the confusion, Benjamin “Bibi” Netanyahu, sitting prime minister and head of the right-wing Likud party, was indicted in November 2019 for bribery, fraud, and breach of trust.

Such a deadlock, in which no political camp could form a coalition and establish a government after elections, has never happened before, despite a host of long-standing divisions in Israeli society—for example, divisions over territorial compromise with the Palestinians; divisions between Jews and Arabs; and conflicts among religious and secular worldviews.

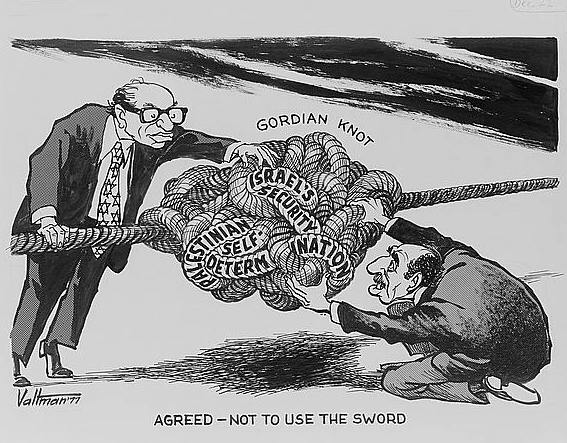

Traditionally, and especially after the so-called Six Day War of 1967, the deepest rift in Israeli society has been over the conflict with the Palestinians.

The Israeli Left has generally advocated a diplomatic solution to the conflict involving Israeli withdrawal from territories occupied in 1967 and the establishment of a Palestinian state on those territories alongside Israel. The Right, for its part, has opposed territorial concessions and recognition of Palestinian national claims to the land.

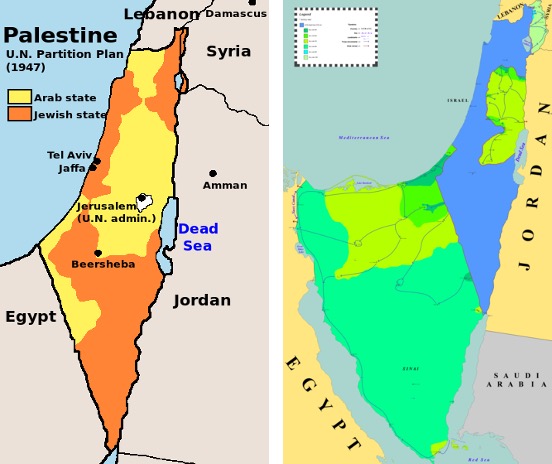

A 1947 map illustrates the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine (left). A map that shows Israeli territory gained during the Six-Day War in 1967. The blue section represents Israel’s pre-war territory, and the green shades represent territory they captured during the war, some of which was returned (right).

Yet despite the significance of Israeli-Palestinian relations to the future of the region, the issue was almost absent from 2019’s election debates. Public discussion instead revolved around Netanyahu’s credentials—so much so that the repeated rounds of elections have been defined as referendums over the prime minister’s leadership.

Netanyahu, a hardliner who opposes territorial compromises and promotes neoconservative socioeconomic policies, first served as prime minister between 1996 and 1999. He returned to the post in 2009, and since then won two more elections to become the longest-serving prime minister in Israeli history. He began to acquire the aura of an invincible politician, amplified by unreserved support from the current American president.

But Netanyahu’s political and personal future came under doubt in late 2016 when the Israeli police launched several criminal investigations that led to his 2019 indictments. The investigations centered on corrupt dealings between Netanyahu and media moguls intended to secure favorable press coverage for the prime minister and his family, as well as allegedly illegal gifts of champagne, Cuban cigars and jewelry, worth around $270,000, from another billionaire.

A 2019 infographic summarizes charges against Benjamin Netanyahu.

The Likud’s main contender in the recent series of elections, the Blue and White Party, has turned the public disgust over Netanyahu’s corruption into its main rallying cry. Founded in February 2019 and headed by Benny Gantz, a retired lieutenant general and former chief of staff of the Israel Defense Forces, Blue and White defined itself as a centrist party. It lacked a distinct ideological character and was actually an amalgam of left-leaning and outright conservative politicians.

Branded by many as an “anti-Bibi party,” Blue and White has avoided presenting fundamental, ideological challenges to Netanyahu’s foreign, security or economic policies. It instead focused its election campaigns mainly on Netanyahu’s corruption cases, hoping that the evolving scandals would help pave the party’s way into government.

During the uncertainty of these many elections, Netanyahu has continued to serve as prime minister of a transitional government, as a lacuna in Israeli law permits an indicted prime minister (as opposed to government ministers) to hold office until conviction.

More astonishingly, Netanyahu has not lost significant support from his political base. He had launched an aggressive campaign describing the investigations, and then the indictment, as a “putsch,” “which hunt,” and political conspiracy to remove him from office, purportedly orchestrated by the judicial system, the police, the Left, the media, and the liberal “elites.”

The prime minister’s cynical attack on the very foundations of Israeli democracy has so far achieved political success: in the March 2020 elections, when it was already known that Netanyahu’s trial was supposed to begin about two weeks after the counting of votes, the Likud won more seats than it had in the elections of September 2019.

A Benny Gantz 2019 campaign banner is displayed at HaShalom Station and Azrielli Center in Tel Aviv.

Furthermore, several weeks after the elections, Blue and White was fractured because, despite earlier promises to the contrary, Gantz entered coalition negotiations with the Likud in an attempt to establish a “unity” or “emergency” government with the professed aim of fighting the coronavirus crisis.

How does Netanyahu maintain power?

While his rhetorical skills and political experience should not be dismissed, the loyalty of Netanyahu’s adherents has deeper historical and cultural roots. Statistical analysis of voting patterns in Israel show that the Likud enjoys strong support from lower- and lower-middle-class voters while Blue and White (like other center-left Zionist parties) are more popular among the upper-middle classes.

Political campaign signs in 2013 in Jaffa, Israel.

And those class divisions overlap to a considerable degree with ethnic divisions: those of the lower classes are more likely to be Jews originating in Muslim countries (Mizrahi Jews, or Mizrahim) while those in upper classes are more likely to be Jews of European origin (Ashkenazi Jews, or Ashkenazim).

The Ethnic Assumptions behind the Zionist Project

The correlation between ethnicity and voting patterns is politically charged and fuels heated debates in Israel, especially during elections. Those tensions have their origin in the history of Jewish migrations to pre-state Palestine and later to Israel, as those migrations brought together Jewish communities of diverse historical and cultural backgrounds.

Those migrations began in the late 19th century, when the Zionist movement arose in Europe. The most influential nationalist movement of the Jewish people, Zionism based its ideology on the historic and religious bond between the Jewish people and Palestine (or the Land of Israel). Zionism assumed that Jewish life outside the homeland was untenable because other nations would never accept Jews—who were a minority everywhere—as full members of society.

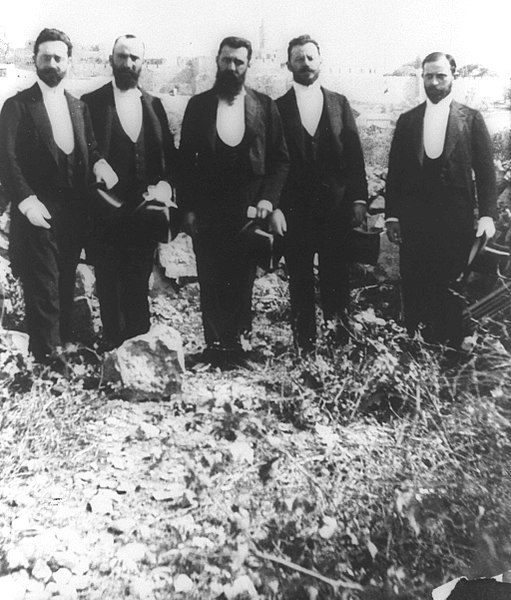

Theodor Herzl (center) with a Zionist delegation in Jerusalem, 1900.

Aspiring to create a national home for the Jews in their ancestral homeland, where they could enjoy physical security and develop their own culture, the Zionist movement started organizing Jewish immigration to Palestine as early as 1881.

Although Jewish migrations into Palestine reflected the basic tenets of Zionist ideology, the majority of immigrants were not motivated by Zionist convictions but by the desire to escape economic troubles and anti-Jewish policies in their countries of origin.

When the first Zionists arrived in Palestine, the country was part of the Ottoman Empire. After World War I it fell to British rule, which ended in 1948 with the establishment of the State of Israel. During those years, most Jewish immigrants to Palestine were Ashkenazim from Europe, while only a small minority came from Muslim countries in the Middle East and North Africa. Ashkenazi Jews thus came to dominate the Jewish community in Palestine, known as the Yishuv.

The period after 1948 saw dramatic demographic transitions. Many Jews from Muslim countries started immigrating to Israel. Those migrations stemmed mainly from anti-Jewish persecutions that started after World War II and escalated following the 1948 Arab-Jewish war in Palestine. While the war resulted in the creation of Israel, it also led to the displacement of large numbers of Palestinian Arabs from their homes.

The mass immigration was a fulfillment of the Zionist vision of “ingathering the Jewish exiles” in the Land of Israel and creating a Jewish majority there, but it presented Israel with severe economic and logistical challenges.

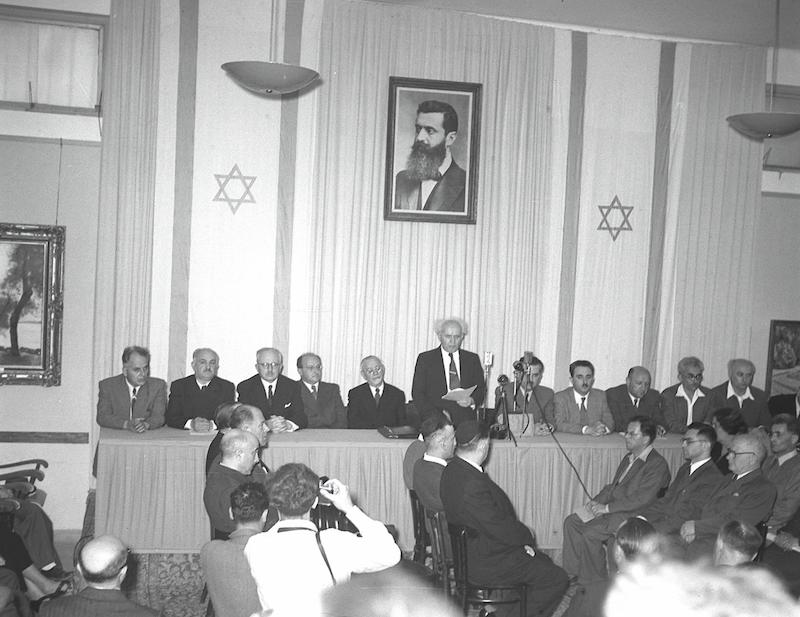

The young state, whose Jewish population numbered around 650,000 upon the declaration of independence, absorbed almost one million new Jewish immigrants during its first decade of statehood.

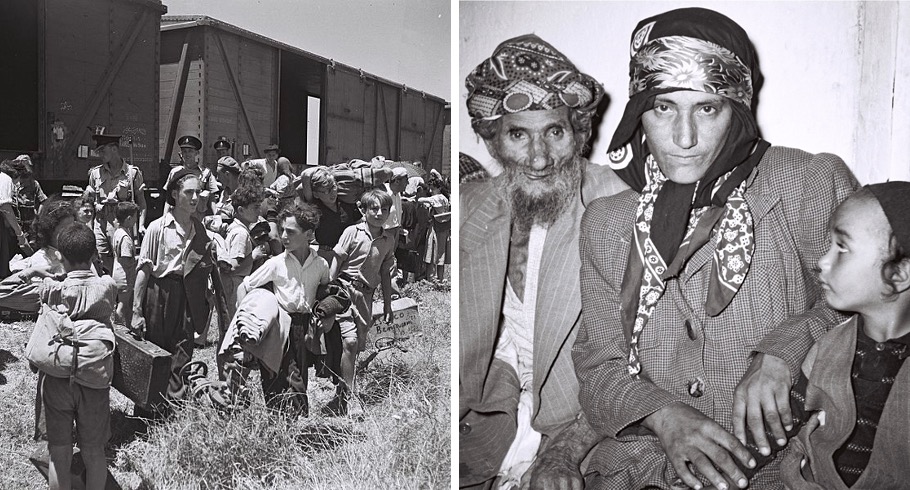

Children orphaned during the Holocaust arrive by train in July 1945 at Atlit Refugee Camp in Mandatory Palestine (left). “Operation Magic Carpet” airlifted Yemenites to Israeli immigration tent camps in 1949 (right). (Photo: Hans Pinn and the Government Press Office)

The immigrants, who were mostly survivors of the Nazi genocide and penniless refugees from Europe and the Muslim world, lived in terrible conditions in various immigrant camps in Israel before they could move to permanent housing and start normal lives.

Both Ashkenazim and Mizrahim lived under those conditions, but there were important differences between the experiences of the two communities. The established Ashkenazim disrespected the cultural background of Mizrahi newcomers, treating them as inferior to Westerners, primitive, backward, and unenlightened in comparison to Ashkenazi Jews.

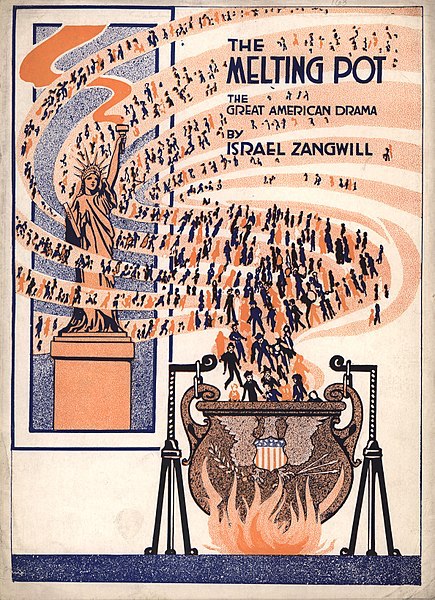

This sort of paternalistic attitude was not reserved only for Mizrahim. The reigning ideology at the time was that of the melting pot, a phrase coined by Zionist activist Israel Zangwill in a 1909 play about immigration to America. Immigrants were expected to shed off their old “diasporic” identities and recreate themselves as “new Jews,” deeply rooted in the revived Hebrew culture promoted by Zionism.

A 1916 theater program for Israel Zangwill’s play, “The Melting Pot.”

But that new culture was modeled on a combination of Jewish traditional ideas and modern—and to some degree secular—Western concepts such as nationalism and socialism, championed by the European-born leaders of the dominant Labor Zionist movement. Mizrahi Jews were supposed to conform to that hegemonic ideal.

Although all Jewish immigrants would experience social and cultural transformation in Israel, the cultural distance between Ashkenazi leaders and Mizrahi immigrants, as well as the imbalance in power between the two groups, determined that Mizrahim were looked upon with special condescension.

On a more practical level, Mizrahi immigrants were more likely to be settled in remote border regions, suffering economic discrimination and isolation from the cultural centers of the country. They also tended to concentrate in low-paying, low-status jobs and receive less education.

They did not quietly submit to this treatment. As early as the 1950s, Mizrahim staged demonstrations against ethnic discrimination and inequality. A more organized form of protest emerged in 1971 with the Israeli Black Panther movement.

A 1974 Israeli Black Panther demonstration in Jerusalem.

Headed by Mizrahi Jews living mostly in slum neighborhoods in Jerusalem, the Israeli panthers borrowed from their American namesakes not only their name but also some of their rhetoric and tactics. They organized large-scale demonstrations, which sometimes resulted in clashes with the police, and called for liquidation of slums, improved political representation for Mizrahim, and equal allocation of resources. The Black Panthers succeeded in raising public awareness, but more significant influence in the political arena came in the late 1970s.

The “Upheaval”

The year 1977 is known in Israeli history as the year of the “upheaval.” In the elections of that year, the Likud, led by Menachem Begin, for the first time defeated the Labor movement, which had been in power, in various incarnations, since the establishment of the state, and had in fact dominated Zionist politics in the Yishuv as early as 1930 with the establishment of the powerful Mapai (Land of Israel Workers’ Party, which in 1968 merged with the Labor party).

The stunning victory of the Likud in 1977 had several roots including corruption involving Labor government officials, which coincided with a broader decline of socialist and collectivist values long identified with Labor Zionism. Many citizens were also dissatisfied with the performance of Labor leaders on issues of foreign policy, national security, and the economy. The election results reflected a desire for a changing of the guard.

Before the 2006 election, a truck covered in Likud banners canvasses Jerusalem neighborhoods.

Beneath these proximate causes, the ethnic question also played a role. Before the 1970s, most Mizrahi Jews voted for Mapai, which could offer employment and other benefits. But this reality started to change with the gradual decline of Labor Zionism.

By the elections of 1977 more than half of the Mizrahi voters—many of whom belonged to a younger generation already born in Israel—supported the Likud, while their support for the Labor party diminished. The strong tendency of Mizrahim to vote for the Likud has shaped Israeli politics ever since.

The ethnic question first reared its head in the turbulent elections of 1981, which again ended in victory for the Likud. The elections turned into a sort of a culture war between Ashkenazim, who largely supported Labor, and Mizrahim, who stood behind Begin. Election rallies sometime turned into violent clashes between the two camps.

In a book written around the time of the 1981 elections, Israeli author Amos Oz recorded the following monologue of a Mizrahi resident of a small town near Jerusalem:

“The Mapainiks just wiped out everything that was imprinted on a person… And then they put what they wanted into him… Like we were some kind of dirt. [David] Ben-Gurion himself called us the dust of the earth…But now that Begin is here, believe me, my parents can stand up straight, with pride, and dignity. I’m not religious, either, but my parents are; they’re traditional, and Begin has respect for their beliefs. Your whole problem is that you don’t realize that Begin is prime minister. For you he’s garbage, not prime minister.”

These words shed light on some of the reasons for the alliance between Mizrahi Jews and the Likud. David Ben-Gurion, Israel’s first prime minister and leader of Mapai, had ostracized Begin and considered him an illegitimate coalition partner in the early years of the state. This treatment had contributed to a sense of victimization among long-time right-wing Zionists, who found a common rival of Mizrahim in Labor Zionism.

Although Begin was born in Poland, the quotation above suggests that his victory over the Labor party enabled Mizrahim to regain their dignity vis-à-vis their former Ashkenazi oppressors.

Ethnicity and Religion

The angry man quoted by Amos Oz also refers to the role of religion. Begin was not a strictly religious Jew, but was more so than Labor leaders were. In one of his first interviews after winning the elections of 1977, Begin was asked what style he would adopt as prime minister. He answered, “A good Jewish style.” This style appealed to Mizrahi Jews, who generally saw themselves as traditionalist Jews.

In contrast, Zionism was one of the products of Jewish secularism, a phenomenon that emerged in Europe in the modern period. Zionist ideology rejected the religious Jewish idea that Jews would return from exile to their homeland only upon divine intervention and the arrival of the messiah, arguing instead that return should be achieved through human action. Although the Zionist movement adopted the religious notion of Jewish yearning for the Land of Israel, it was in important respects a revolt against Jewish religious tradition.

The concept of the “new Jew” espoused by Labor Zionists was a project of Western modernization. It emphasized modern “Israeliness”—the product of the Zionist revolution—over “Jewishness,” which was identified with the diasporic past. This approach was less appealing for Jews originating in Muslim countries, many of whom had remained more rooted in Jewish tradition.

While Mizrahi Jews were alienated by the concept of the new Jew, they found that the Likud was more open to expressions of religious tradition, which were important for their identity as Jews.

Foreign Policy and Jewish Identity

As Likud supporters, many Mizrahim also adopted the hawkish attitude of that party on questions of security and foreign relations. This applied mainly to relations with the Palestinians. Israel had begun colonizing the territories taken in 1967 when Labor was still in power. But after 1977 the Likud significantly expanded the colonization with the purpose of “creating facts on the ground” that would prevent the establishment of a Palestinian state.

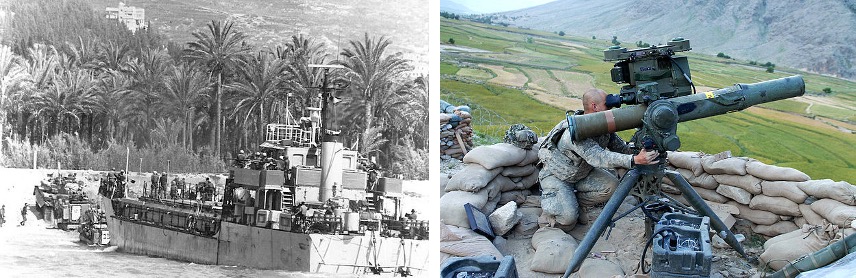

Begin signed a peace agreement with Egypt in 1979 which involved Israeli withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula, which Israel had occupied in 1967. But Begin refused to include in the peace treaty a provision for Palestinian autonomy which could have served as a step toward a Palestinian state. As prime minister, Begin was also responsible for the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

On June 9, 1982, Israeli armored vehicles exit a landing craft at the mouth of Lebanon’s Awali River (left). Armed with American made BGM-71 TOW anti-tank missiles, Israeli forces destroyed 11 Lebanese tanks on June 11, 1982 (right).

Observers have tried to understand the support of many Mizrahi Jews for such aggressive policies. Some believe that Mizrahim have developed an anti-Arab approach as a result of their experience living under Muslim rule in their countries of origin, especially during the post-World War II persecutions. Others believe that the strong emphasis on Jewish identity has led to an exclusivist nationalist worldview.

But there was nothing inevitable about the connection between Mizrahi identity and right-wing politics. The Black Panthers, for instance, embraced a leftist agenda and saw Palestinian Arabs as potential allies in their struggle against the Ashkenazi Zionist establishment. Likewise, in the 1950s and 1960s the Israeli Communist party received significant support from Iraqi Jews, mainly because of the party’s anti-Mapai stance and respect for Arab culture.

More recently, other groups have emerged that combine the Mizrahi struggle with left-wing values. Moreover, the staunchest opposition in Israel to territorial compromise with the Palestinians has traditionally come from predominantly Ashkenazi groups, such as the nationalist religious right.

This suggests, perhaps, that the roots of the bond between Mizrahi Jews and the Likud are to be found not so much in the party’s hawkish positions but more in the question of Jewish identity, sense of belonging, and animosity towards the Labor movement. This animosity lingers on even though the party has remained in opposition since 1977, except for short periods in the 1980s and 1990s.

The emphasis on group identity and tribalism is evident in the Israeli political system as a whole. As we saw, just as traditionalist Mizrahi Jews of lower economic classes tend to vote for the Right, so too secular Ashkenazim of higher economic status tend to vote for the center-left.

Mizrahi support for right-wing politicians should be seen partly as the expression of ethnic and class grievances directed, as in so many other countries right now, at “elites” and “the establishment.”

Turning Identity into Ideology

Netanyahu has been using those divisions and sentiments throughout his political career. The slogan for his first election campaign in 1996 was “Netanyahu. It’s good for the Jews.” One year after being elected, he was recorded saying to a rabbi popular among Mizrahi Jews that “the left-wing people have forgotten what it means to be Jewish.”

Netanyahu at the time was trying to fend off pressure to pursue the peace process initiated by the Labor government in 1993, which involved withdrawal from some territories occupied in 1967 and handing over partial control of those territories to the Palestinians. Netanyahu told the rabbi that the left-wing people “think they can put our security in the hands of the Arabs.”

Although Netanyahu, like Begin, is of Ashkenazi extraction, already during his first term he engaged in a battle against the “old elites:” the media, academia, the intelligentsia and other institutions historically identified with the center-left. Part of his appeal to right-wing voters has apparently been his antagonistic attitude toward, and sense of victimization by, those systems, which, for their part, have largely rejected him.

Netanyahu intensified his anti-elite rhetoric in response to the present corruption investigations. He has been depicting the work of the police and judicial system not only as a personal attack against him, but against his entire political camp.

Among segments of the Right a narrative took hold that condemns the Netanyahu investigations as a “deep state” conspiracy or an attempt by the privileged class to repress the unprivileged; as an effort by the old elite to return to power by ousting the outsiders in Israeli society, to reverse the upward mobility of Mizrahim enabled by the Likud victory in 1977. No serious evidence, however, has been provided to support these claims.

A February 2020 tweet of a Likud party sign distributed throughout Jerusalem that shows Ahmad Tibi, a Knesset member of the Joint List, carrying Benny Gantz on his back. The message reads: “Without Ahmad Tibi there is no Gantz government.”

Netanyahu has also mobilized nationalist and even racist sentiments for his political struggle. In the recent rounds of elections, it became clear that the center-left could only form a government that would remove Netanyahu from office by joining forces with the Joint List—a political alliance of parties representing mainly Palestinian Arab citizens of Israel, who comprise about 20 percent of Israel’s population of almost 9 million.

Various right-wing figures have consistently labeled Arab politicians as a “fifth column,” accusing them of promoting the Palestinian nationalist cause instead of the civil concerns of their constituency in Israel.

Arab parties, for their part, have been reluctant to join Israeli governments, as such a step would mean official sanction for Israeli policies toward their Palestinian brethren living in the territories taken in 1967 (who are not Israeli citizens). The current leader of the Joint List, Ayman Odeh, however, has changed course, pushing for a policy of Arab political influence and integration rather than separatism.

Joint List supporters hang campaign posters during the 2015 elections.

Aware of the threat that an Arab-Jewish association would pose to his rule, Netanyahu initiated a delegitimization campaign against a potential alliance between the center-left and the Joint list, denouncing it as an immediate danger and existential threat to Israel.

To be sure, political partnership with the Joint List raises fundamental difficulties, since members of the list oppose the definition of Israel as a Jewish state—a position that requires a serious ideological compromise from a Zionist perspective.

Yet Netanyahu’s rhetoric seems to appeal to deep-seated fears and prejudice of some of his supporters, regardless of their ethnic origin. He used similar tactics on election day in 2015, when he released a video warning that the “right-wing government is in danger” because “the Arab voters are coming out in droves to the polls.”

After the March 2020 elections, an effort to form a center-left coalition with the support of the Joint List eventually failed. Meanwhile, Netanyahu’s trial was postponed as the minister of justice, a Netanyahu loyalist, ordered a freeze on court activity as part of coronavirus emergency measures.

Israeli Arab women selling goods in 2016 at the Arab Bazaar in the Old City of Jerusalem.

Regardless of the outcome of Netanyahu’s legal saga and the current political crisis, a longer-term view suggests that, in light of the reality outlined in this article, the Israeli center-left can regain political power only through cooperation with Arab citizens and their representatives.

Read more on Israel and Palestine: The Two State Solution under Siege?; The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict; The Jordan River; The 1967 War; and Jerusalem.

Read more on the Middle East: The Fate of the Kurds; Turkey’s Politics; the Alawites and Syria; ISIS; Islamic Politics in Egypt; The Religious Divide in Iraq; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; Feminism in Egypt; Yemen Civil War; U.S.-Iraq Relations; and The U.S. War in Iraq.

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Understanding the Middle East; Yemen: Inside The Forgotten War; Women in the Mideast and North Africa; and the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring.

Bashkin, Orit, Impossible Exodus: Iraqi Jews in Israel (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2017).

Chetrit, Sami Shalom, “Mizrahi Politics in Israel: Between Integration and Alternative,” Journal of Palestine Studies,29/4 (Autumn 2000), pp. 51-65.

Fischbach, Michael, Black Power and Palestine: Transnational Countries of Color (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019).

Ghanem, Asad, “Israel’s Joint List Has a New Strategy,” Foreign Affairs, January 23, 2020.

Hakohen, Devorah, Immigrants in turmoil: Mass Immigration to Israel and Its Repercussions in the 1950s and After (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2003).

Jamal, Amal, “Strategies of Minority Struggle for Equality in Ethnic States: Arab Politics in Israel,” Citizenship Studies, 11/3 (July 2007), pp. 263–282.

Morris, Benny, Righteous Victims: A History of the Zionist-Arab conflict, 1881-1998 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999).

Oz, Amos, In the Land of Israel (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983).

Shapira, Anita, Israel: A History (Waltham, Mass.: Brandeis University Press, 2012).

Shilon, Avi, Menachem Begin: A Life (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012).

Smooha, Sammy, Israel: Pluralism and Conflict (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978).