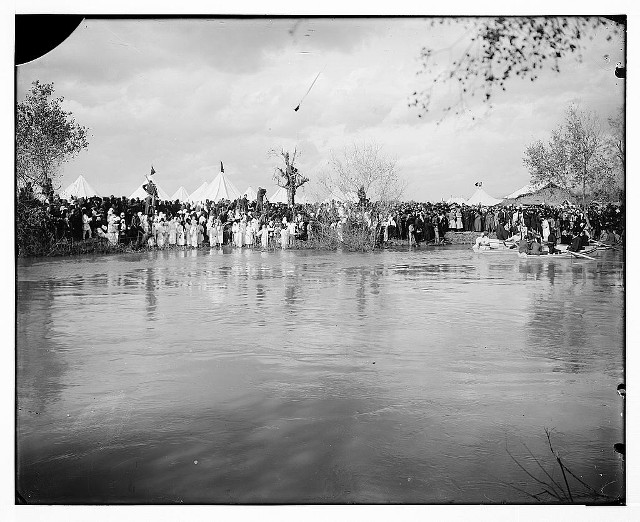

For centuries, baptisms have been performed in the Jordan River, considered holy by many religious communities.

As the site of the baptism of Jesus Christ, the Jordan River is the source of all holy water in Christianity and has for centuries attracted pilgrims from across the world. Over the last 60 years, however, the river has fallen victim to the ongoing regional conflict and been reduced to a polluted muddy stream. Francesca de Châtel travels to the banks of the most holy and contested transboundary river in the Middle East and looks at the causes of the Jordan River’s demise and what is being done to restore it.

Read more from Origins:

On Rivers and the Environment: Who Owns the Nile?; The World Water Crisis; The Changing Arctic; Climate Change and Human Population ; Global Food Crisis; Over-Fishing; and Rome's Rivers.

On Religion: The Changing Face of Global Christianity.

On the Middle East: The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict; Islam in Egypt; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; the Alawites and Syria; U.S.-Iranian Relations; U.S.-Iraq Relations; and Turkish Politics.

Listen to the Origins podcast History Talk : The Syrian Civil War: Alawites, Women's Rights, and the Arab Spring .

Dressed in white gowns, the group of Russian pilgrims gathered silently by the steps that led into the river. The priest, a tall figure with shoulder-length hair and a beard, intoned a hymn and the pilgrims joined in, bowing their heads in prayer. Barely five meters away on the opposite shore, two Jordanian soldiers looked on from the shelter of a reed-covered platform – no visitors had come to visit their side of the river yet that day.

As the pilgrims sang, the priest slowly descended into the muddy water, which reached only to his thighs, so that he almost had to lie down to immerse himself fully. He emerged with closed eyes, gasping for breath. The women, their heads covered, lined up on the steps, some holding young children by the hand.

One by one, they descended into the water, knelt in front of the priest and crossed themselves before he placed his hand on their head and immersed them in the water. Three times – in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit.

Baptism at Qasr al Yehud, West Bank. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

Meanwhile, a group of young Americans sat in the shade of some palm trees on the bank and listened to their guide, an American woman wearing a safari hat and khaki desert trousers, who explained the significance of the holy Jordan River.

“You can see that the river is quite muddy,” she said as she pointed to the timid murky flow, “but it’s actually not dirty, because there’s so many bends in the river.” Her audience nodded and one girl complained it was too hot.

The Russian baptism ritual completed, the pilgrims emerged from the water and took photos of one another by the river, while three young boys started a water fight in a corner of the baptismal pool. Their mothers scolded them loudly and dragged them off to the showers. Half an hour later, after a visit to the gift shop, both groups were getting back on the Israeli tourist buses, off to the next stop on their day tour of biblical sites.

As the boundary of the Holy Land and the site of the baptism of Jesus Christ, the Jordan River is the source of all holy water in Christianity. For centuries, pilgrims have travelled long distances to immerse themselves in the river and even today nearly a million visitors annually flock to the three baptism sites in Israel, Jordan, and the Palestinian West Bank to follow in the footsteps of Christ.

Top: Pilgrims bathing in the Jordan River. Bottom: Scene on the Jordan River. Source: Lynch, 1853.

Top: Pilgrims bathing in the Jordan River. Bottom: Scene on the Jordan River. Source: Lynch, 1853.

Over the past century, however, the Jordan River has been drawn deep into the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Once a meandering river full of rapids and cascades, the Jordan has been extensively developed since the 1950s, with dams, diversion canals, and large-scale irrigation projects on the river itself, its tributaries, and its headwaters. As a result, flow has been reduced to about a tenth of its historic level. And water quality has sharply deteriorated, with raw sewage and agricultural runoff polluting the remaining water.

The Jordan River is both a cause of conflict and tension as well as a potential source of regional cooperation. It became one of the most contested transboundary rivers in the Middle East with the creation of Israel in 1948, and, since 1967, a heavily militarized political border.

In the face of this highly complex situation, the regional NGO Friends of the Earth Middle East (FoEME) is nonetheless working to revive the Jordan River, restoring the basin as a single interconnected ecosystem and a shared cultural heritage site that transcends political boundaries.

The Jordan River has since biblical times been imbued with powerful symbolic meanings: it is a boundary and a crossing point, a metaphor for spiritual rebirth and salvation, and a source of holy water.

But the river’s symbolic significance became even more layered in the 20th century. As the physical river and its tributaries underwent far-reaching infrastructural changes, the Jordan River took up new meanings as a geopolitical border, a contested transboundary watercourse, a threatened ecosystem, and a tightly regulated water resource system.

The strength of these different geopolitical, hydrological, environmental, and religious narratives is sharply crystallized on the Lower Jordan River where holiness, pollution, hydropolitics, and national boundaries collide.

Source of Holy Water and Pilgrimage Site

The Jordan River plays an important role in the Old Testament as the border of the land that God gives to the Israelites. In the New Testament, John’s baptism of Jesus forms a seminal moment in the life of Christ and marks a defining event in the Christian Church.

The baptism also altered the spiritual status of the water of the Jordan River.

Early Christian writers asserted that Christ’s immersion in the Jordan sanctified the river’s water, which in turn made all water holy. The Jordan was seen as the prototypical “river of life,” but also the site of a divine manifestation of God, for just as water had been the primeval element that witnessed God’s creation, the Jordan had witnessed the beginning of the Gospels.

The baptism of Christ as depicted in the Arian Baptistery in Ravenna, Italy. Source: Holly Hayes, 2008 (Creative Commons).

The baptism of Christ as depicted in the Arian Baptistery in Ravenna, Italy. Source: Holly Hayes, 2008 (Creative Commons).

The site where John baptized Jesus in the Jordan River became an important pilgrimage site from the 4th century CE.

Several writers recorded their visits here, including the 6th-century geographer Theodosius who described a marble column topped by an iron cross that had been erected at the place where Jesus was thought to have been baptized. He also wrote about the Church of St. John the Baptist, built by the Emperor Anastasius, which “stands on great vaults which are high enough for the times when the Jordan is in flood.”

The sick and disabled also came to the Jordan for healing, as Jacinthus the Presbyter related in the late 11th century: “On the feast of the Epiphany cripples and sick people come and, using the rope to steady themselves, go down to dip themselves in the water: women who are barren also come here.”

For those who were too sick to make the journey, water could also be drawn from the river and brought to them.

Thus the Russian Princess Euphrosine of Polatsk, who had come to Jerusalem to die in the 12th century, was unable to travel to the Jordan but was given a bottle of holy water by an acquaintance, “which she received with joy and gratitude, drinking it and spreading it over her body to wash away the sins of the past.”

Russian pilgrims at the Jordan. Source: Catalogue of photographs made by the American Colony (1898-1914).

Russian pilgrims at the Jordan. Source: Catalogue of photographs made by the American Colony (1898-1914).

By the late Middle Ages, the Jordan was venerated almost exclusively as a relic of Jesus Christ, possessing powerful spiritual forces. A late-13th-century guidebook gave just one reason for immersion in the river: “these are the waters which came into contact with the body of Christ, our Redeemer.”

Writing in 1483, Felix Faber described how several knights of his party had jumped into the Jordan fully clothed, convinced that their clothes would become impenetrable to enemy weapons. Others dipped bells in the river and believed that ringing them would stave off lightning and thunder.

The 17th-century English cleric Henry Maundrell described how pilgrims also cut branches off the reeds on the riverbanks, while later accounts by 19th-century Russian travelers described pilgrims taking bottles of holy water and burial shrouds dipped in the river home with them.

A Divided River and How We Think about It

From its sources on the slopes of Mount Hermon, the Jordan River winds its way through the Jordan River Valley over a distance of about 225 km to discharge into the Dead Sea, the lowest point on earth at –422 m.

The river’s headwaters, the Dan, Hasbani, and Banias, originate in Israel, Lebanon, and the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights respectively, and meet inside Israel to form the Upper Jordan River, which flows into Lake Tiberias (also known as Lake Kinneret or the Sea of Galilee), Israel’s largest freshwater reservoir that supplies approximately one third of the country’s annual water requirements.

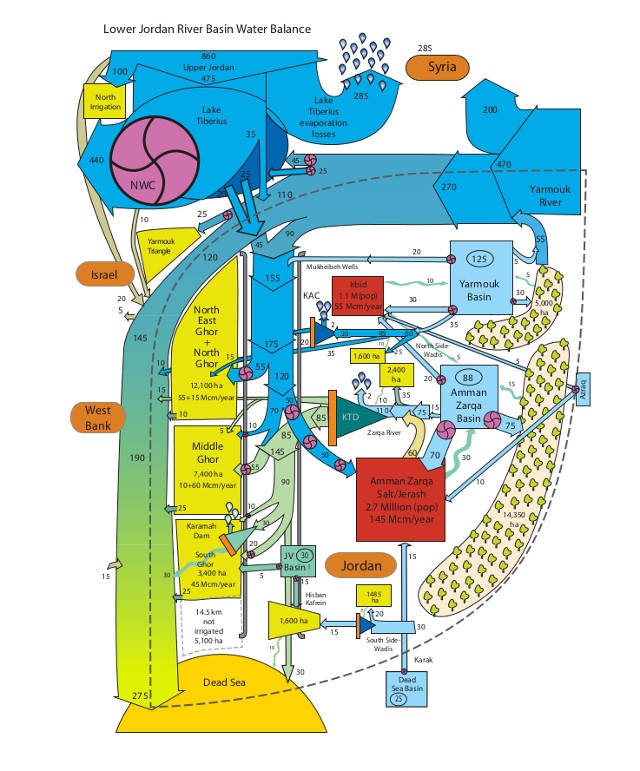

South of Lake Tiberias, the Lower Jordan River covers a distance of 143 km to the Dead Sea. Historically, this part of the river was fed by water from Lake Tiberias, the Yarmouk River (the Jordan River’s largest tributary) and several seasonal wadis. Today, water levels in this part of the river have been sharply reduced due to large-scale regulation and diversion works in Israel, Jordan, and Syria.

By 2009, the Lower Jordan River’s historic annual flow of 1,300 million cubic meters (MCM) had been reduced to an estimated 20-30 MCM. Moreover, most of the fresh water in this part of the river has been replaced with saline flows, water from fishponds, sewage, and agricultural runoff.

The 20th-century transformation of the Jordan River has been extensively analyzed from the perspective of international relations, international law, politics, geography, history, hydrology, ecology, and social studies. It has been used as a textbook example of the disputed transboundary watercourse in a water-scarce region par excellence, caught in the middle of a protracted political conflict and subject to multilateral power struggles.

This extensive body of research and analysis has further fragmented and abstracted perceptions of the Jordan.

Thus the river is now commonly described and analyzed as a composite of separate units: the Upper Jordan River, Lake Tiberias/Lake Kinneret, the Yarmouk River and the Lower Jordan River. The drastic infrastructural interventions along the river, which have fundamentally altered water flow, water quality and local ecosystems, are schematically represented in conceptual flow diagrams.

Historically described as “the most crooked river in the world,” “sometimes dashing along in rapids by the base of a mountain, sometimes flowing between low banks,” the river is now a system that has been transformed into a series of contiguous and artificially controlled water bodies.

Even the water itself has been dissected, quantified, and qualified: separating the saline from the fresh; diverting drinking water away from the valley and pumping raw sewage back into the river; extracting irrigation water from side wadis, tributaries, and dam reservoirs; and releasing contaminated return flows back into the river.

Lower Jordan River Water Balance 1950-1975. Source: Courcier et al., 2005.

Lower Jordan River Water Balance 1950-1975. Source: Courcier et al., 2005.

A Geopolitical and Religious Border

Despite the extensive infrastructural developments that have led to a dramatic drop in water levels and deterioration in water quality, public awareness of the slow demise of the Lower Jordan remains low. The main reason for this void is that the river itself has been largely inaccessible and thus invisible since 1967.

As the geopolitical border between Jordan to the east and Israel and the Palestinian West Bank to the west, the Lower Jordan River remains a largely closed – and in many places mined – military zone that can only be reached at a few points along its course.

The only place where Jordanians can visit the river is at the Al Maghtas Baptism Site just north of the Dead Sea, a location that has only been accessible since Jordan signed the Peace Treaty with Israel in 1994.

Israelis have no access south of the Yarmouk River, while Palestinians can only access the river at the Israeli-controlled baptism site in the West Bank, Qasr al Yehud.

The fact that the physical river has been largely out of sight since 1967 further strengthens its conceptual representations and increases the disconnect between the physical river and its mythical image.

This same disconnect exists in the religious realm.

The reality of a diminished, polluted river does not appear to affect the spiritual value of the water. The three baptism locations – the Baptism Site/Al Maghtas in Jordan, Qasr al Yehud in the West Bank, and the Yardenit Baptismal Site in Israel – present themselves as religious places focused on biblical history and archaeological remains, and gloss over the many other narratives that play out along the river.

Yet the region’s recent history flows just beneath the surface, cluttering the mythical narrative of the Jordan River as a source of spiritual cleansing and renewal with the starkly utilitarian and political narratives of modernity that materialize in the form of dams, sewage flows, landmines, and security checkpoints.

Just north of the Dead Sea, the Al Maghtas/Baptism Site in Jordan and the Israeli-operated Qasr al Yehud site in the West Bank lie just a few meters apart on the two banks of the river with an invisible border running between them. Both sites argue that theirs is the “authentic” site of Jesus’ baptism, presenting biblical, archaeological and historical evidence to corroborate their claim.

The Lower Jordan River from Al Maghtas/The Baptism Site in Jordan looking at Qasr al Yehud in the West Bank. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The Lower Jordan River from Al Maghtas/The Baptism Site in Jordan looking at Qasr al Yehud in the West Bank. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

As one of the earliest Christian pilgrimage sites, the Jordanian Al Maghtas/Baptism Site was largely abandoned after World War I and became part of an inaccessible military zone after the 1967 Six-Day War.

After Israel and Jordan signed a peace treaty in 1994, the area was demined and “rediscovered.”

Extensive archaeological work uncovered a series of churches, monasteries and other remains, including the cave where John the Baptist retreated in the desert, and the church described by Theodosius in the 6th century. Together with further textual references, these archaeological finds have led the Jordanian authorities to declare this to be the authentic baptism site.

The remnants of a Byzantine chapel built on the Jordan River, on the site where Jesus is said to have been baptized, Al Maghtas/The Baptism Site, Jordan. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The remnants of a Byzantine chapel built on the Jordan River, on the site where Jesus is said to have been baptized, Al Maghtas/The Baptism Site, Jordan. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The Jordanian claim has been further strengthened by a series of “letters of authentication” from world religious leaders, and visits by three popes and numerous monarchs, heads of state, and other dignitaries.

Moreover, the Jordanian government’s move to donate national land for the establishment of 12 churches of different denominations on the site adds a layer of modern mythology to the layers of biblical, archaeological, and historical mythology.

Just like its transboundary neighbor, the Qasr al Yehud site in the Israeli-occupied West Bank uses archaeological remains and historic accounts to prove it is the authentic site of Jesus’ baptism. It refers to the 6th-century Madaba Map, which places “Bethabara” (Bethany Beyond the Jordan) and the church of John the Baptist west of the Jordan River.

The Madaba Map, Madaba, Jordan. Source: Soon Kim, 2013 (Creative Commons).

The Madaba Map, Madaba, Jordan. Source: Soon Kim, 2013 (Creative Commons).

While the site at Qasr al Yehud could in the future become a Palestinian site as part of a peace settlement, for the time being it remains firmly under Israeli control, as it has been since 1967. Like Al Maghtas in Jordan, the area around Qasr al Yehud was affected by the regional conflict and became an inaccessible military zone after 1967, cordoned off by a security fence and surrounded by minefields.

After 1980, limited access was granted to local church communities who came to celebrate Epiphany and Easter. During the rest of the year, pilgrims could only visit the site by appointment with a military escort.

However, after the papal visit in 2000, Israel decided to refurbish the site, a project which was jointly implemented by the Israeli Nature and Parks Authority and the Civil Administration, the Israeli body that governs the West Bank. Funding for the project came from the Israeli Ministry of Tourism and the Ministry for Regional Cooperation, a controversial move since part of the $2 million budget was effectively drawn from funds reserved for West Bank development.

In addition to being a biblical site, Qasr al Yehud also makes a number of political statements, as it competes for authenticity with its Jordanian neighbor, but also reiterates and reinforces the Israeli presence in the West Bank.

Pilgrims at Qasr al Yehud, West Bank. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

Pilgrims at Qasr al Yehud, West Bank. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The river that runs between the two sites has also become a more complex and layered space since the 1950s. Its image as a holy river has been overshadowed by infrastructural development, which approached the river as a utilitarian water resource system harnessed to meet the demands of a growing population in the region.

After the creation of the state of Israel in 1948, it was drawn into the regional conflict as a contested resource. Israel forcefully imposed the construction and operation of its National Water Carrier – a 200-kilometer conduit that conveys more than 300 MCM of water annually from Lake Tiberias to cities along the Israeli coast and further south to the Negev – prevented Jordanian, Lebanese, and Syrian attempts to develop the river, and entirely barred Palestinians from accessing it.

Meanwhile Syria, which lost access to the Upper Jordan River and Lake Tiberias with Israel’s occupation of the Golan Heights in 1967, turned to the development of the Yarmouk River and its tributaries, where it built 38 dams in the following decades.

Jordan also started diverting water from the Yarmouk and Zarqa Rivers into the King Abdullah Canal. Unsurprisingly, the first victim of these unilateral development strategies was the Lower Jordan River itself, which has been reduced to around 2% of its historic flow.

In addition, water quality in this part of the river south of the Alumot Dam has been severely impaired, with saline flows, agricultural runoff, water from fishponds, and poorly treated sewage being released by all communities along the river so that its water is unsuitable for use in any sector. The degradation of the Jordan River has also caused a 50% reduction in biodiversity.

Raw sewage being released in the Lower Jordan River at the Alumot Dam, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

Raw sewage being released in the Lower Jordan River at the Alumot Dam, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The Lower Jordan River below the Alumot Dam. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The Lower Jordan River below the Alumot Dam. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

FoEME has drawn attention to the severe degradation of the Lower Jordan River through several detailed studies and a wide-reaching international campaign to rehabilitate it.

In 2010, the organization also warned that organic pollution posed a serious public health threat at the southern baptism sites, which led to a flurry of media coverage over whether the river was safe for immersion at the baptism site in the West Bank.

The Israeli authorities subsequently issued statements declaring that the water was regularly monitored and safe for immersion. But as neither the Israelis nor the Jordanians make comprehensive long-term data publicly available, it is easy to speculate about the degree of pollution and whether it poses a public health threat.

The Yardenit Baptismal Site in Israel is far removed from such unsettling reports of polluted holy water and the history of conflict and shifting borderlines. Situated just south of Lake Tiberias before the Alumot Dam, Yardenit gives a bucolic impression of the Jordan River as a free-flowing, tree-lined river.

The Lower Jordan River flowing south seen from the Degania Dam and above the Alumot Dam, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The Lower Jordan River flowing south seen from the Degania Dam and above the Alumot Dam, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

According to the Yardenit website, this is one of the only places along the Jordan River where the river still flows naturally. In fact, from a hydraulic point of view, the river here is an artificial reservoir, regulated by the upstream Degania Dam that controls inflow from Lake Tiberias, and the Alumot Dam, 1.5 km downstream. The water at Yardenit is essentially the same as that in Lake Tiberias and therefore close to drinking-water quality.

In this “pristine” setting, the site presents a bright and uncomplicated story that merges spirituality, tourism and consumerism into a seamless modern-day religious-retail experience. The visitors’ center, designed in the shape of a church’s nave, includes a large gift shop selling everything from bibles and olivewood crucifixes to holy water (125 ml, $6) and “I Was Baptized in the Jordan River” T-shirts.

Across from the gift shop, the Manna Restaurant serves “biblical food,” including St. Peter’s Fish and dates produced at the nearby Kibbutz Kinneret. Outside near the baptismal pools, visitors can pick up a video recording of their own baptism ceremony and buy empty plastic bottles and jerry cans to fill up with water from the Jordan River.

The Yardenit Baptismal Site, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The Yardenit Baptismal Site, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

Holy water in the Yardenit gift shop, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

Holy water in the Yardenit gift shop, Israel. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

As Yardenit is more than 100 kilometers from the two southern sites, there is less need to legitimize it as the authentic site of Jesus’ baptism – tourists who visit as part of a day tour may not even be aware that there are any other sites.

Yet, by omitting any biblical references to Bethany Beyond the Jordan and emphasizing the “scenic landscapes [described in the Bible…] that have been preserved to this day,” the site’s tourist brochure implicitly suggests that this is the authentic site of baptism, or at least the place where it can be relived most authentically.

Billed as “the perfect combination of the [sic] Christian heritage, the exciting sights of the Holy Land and the history of civilization,” the Yardenit Site – like the two southern sites – also weaves in subtle political narratives, firmly rooting the story of baptism into ancient – and, implicitly, more recent – Jewish history in the Holy Land.

The site’s location on the grounds of Kibbutz Kinneret, the second kibbutz founded in Mandate Palestine, ties the biblical event of the baptism of Jesus into Zionist narratives.

Thus while the three baptism sites present themselves as religious sites that focus on biblical history and offer a space for spiritual reflection, each also represents particular political, nationalist, and economic interests, while at the same time glossing over the profound changes to the holy river itself.

Pilgrims who visit these sites appear unconcerned by or unaware of the physical changes to the river, which in their view do not affect its spiritual qualities.

Msgr. Maroun Lahham, the Latin Patriarch Vicar General of Jordan, appeared indifferent to the state of the river, considering its physicality to be almost irrelevant. “From a religious perspective it does not matter whether the water is dense or light, clear or cloudy, polluted or not polluted,” he said. “This does not touch upon the aspect of faith. Pollution is a Western concern, it is Cartesian. Descartes’ influence stopped on the northern shores of the Mediterranean.”

The physical and spiritual realms continue to exist separately, allowing the image of the holy Jordan River to persist independently of the altered physical river. An official at Al Maghtas in Jordan said that the river’s holy qualities are unchangeable. “We don’t like the word ‘pollution,’” he said.

“The water quality has been impaired by return flow of fertilizer, pesticides, saline water and treated and untreated sewage water along the whole river course. All this does not affect the spiritual quality of the river though: the Jordan is the Jordan. It is a holy river.”

Reviving the Jordan River

Despite the continued zero-sum struggle for the river’s water, efforts are being made to revive the Jordan River. FoEME has developed a comprehensive rehabilitation plan for the Lower Jordan River based on extensive research in Israel, Jordan, and Palestine.

The plan outlines concrete steps to remove pollutants from the river, return fresh water flow to it, and ensure Palestinian rights to a share of the river’s water are honored. It highlights the crucial importance of cross-border cooperation and of treating the river basin as a single interconnected ecosystem that transcends political boundaries and disputes.

Partly as a result of FoEMe’s advocacy efforts, Israel started releasing 1,000 m3/hour of fresh water from the Alumot Dam into the Lower Jordan River in May 2013, with a commitment to increase this amount to an annual 30 MCM.

Israel started releasing fresh water into the Lower Jordan River in May 2013. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

Israel started releasing fresh water into the Lower Jordan River in May 2013. Source: Francesca de Châtel, 2013.

The Israeli Ministry of Environment has also outlined a master plan for the upper part of the Lower Jordan River up to the Bezeq Stream, the border with the Palestinian West Bank.

In addition, the operation of a new sewage treatment plant near the Alumot Dam by 2015 will remove sewage from the river. If Jordanian and Palestinian plans to build wastewater treatments plants in their part of the watershed are realized, half a century of using the Jordan as a sewage canal could be put to an end, according to FoEME.

However, the removal of the various effluents discharged by Israel, Jordan and Palestine could cause the drying up of the river. FoEME therefore recommends that 400-600 MCM/year of fresh water be returned to the river and that the river be allowed to flood once a year in order to maintain a healthy ecosystem.

While critics argue that none of the riparians are willing or able to give up their acquired share of the river, FoEME says it has identified over 1 billion cubic meters of water that can be saved in Israel, Jordan, and Syria.

The organization is advocating for the establishment of an international commission to manage the Lower Jordan River basin and is currently developing a cross-border master plan. It is also working towards the creation of a transboundary ecological peace park on the border between Israel and Jordan.

FoEME’s broad-ranging Jordan River Rehabilitation Project also seeks to engage and involve Christian, Jewish, and Muslim religious leaders both in the region and internationally in an effort to raise awareness of the importance of preserving the Jordan River Valley as a site of shared religious and cultural-historical heritage.

In November 2013, the organization published a series of Faith-Based Toolkits (Christian, Jewish, Muslim), which religious leaders are encouraged to use in their sermons and activities to engage faith communities in the region and beyond.

Christian, Jewish, and Muslim religious leaders from Israel, Jordan, and Palestine also gathered at a regional conference on the Dead Sea in Jordan in November 2013 where they endorsed the Covenant for the Jordan River drawn up by FoEME. The document calls upon regional governments to work towards the rehabilitation of the Lower Jordan Valley, which “must be counted as part of the heritage of humankind.”

Thus, against all odds, the first steps towards reviving the Lower Jordan River have been taken. And while the Jordan River will never return to its natural state, it could again becoming a living river and a carrier of holy water that is not only worshipped in a religious context but also revered and respected as the key to life and livelihood in this arid region.

A series reports, concept documents and other publications issued by Friends of the Earth Middle East between 2010 and 2014 are available at www.foeme.org.

Courcier, R., Venot, J. P., Molle, F., Historical transformations of the lower Jordan river basin (in Jordan): Changes in water use and projections (1950-2025). Comprehensive Assessment Research Report 9. Colombo, Sri Lanka: Comprehensive Assessment Secretariat, 2005.

Gal, Zvi, Baptism in the Jordan River, A Renewal of Faith, Israel Nature and Parks Authority, 2011.

Havrelock, Rachel, River Jordan, The Mythology of a Dividing Line, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2011.

Hillel, Daniel, Rivers of Eden, The Struggle for Water and the Quest for Peace in the Middle East, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1994.

Jensen, Robin M., Living Water, Images, Symbols, and Settings of Early Christian Baptism, Brill, Leiden, 2011.

Lowi, M., Water and power, the politics of a scarce resource in the Jordan River Basin, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Lynch, W.F., Narrative of the United States’ Expedition to the River Jordan and the Dead Sea, Blanchard and Lea, Philadelphia, 1853.

Peppard, Christiana Z., ‘Troubling waters: the Jordan River between religious imagination and environmental degradation’, Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 20 April 2013, pp. 1-11.

Rouyer, Alwyn R., Turning Water into Politics, The Water Issue in the Palestinian-Israeli Conflict, Macmillan Press Ltd, London, 2000.

Sumption, Jonathan, Pilgrimage, an Image of Mediaeval Religion, Faber & Faber, London, 1975.

UN-ESCWA & BGR (United Nations Economic and Social Committee for Western Asia and Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe), Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia, Beirut, 2013, Chap. 6.

Wilkinson, John, Jerusalem Pilgrims Before the Crusades, Aris & Phillips Ltd, Warminster, 1977.