To use the phrase "Middle Eastern feminism" will strike many in the West as an oxymoron. There is a pervasive sense that custom and religion conspire to oppress women across that region. In fact, the situation is more complicated than that. This month historian Gulsah Torunoglu examines the role Egyptian feminists played in the 2011-14 revolutionary era and traces the powerful tradition of Egyptian feminism that stretches back to the nineteenth century.

Read these insightful Origins articles for more on the Middle East: Islamic Politics in Egypt; The Religious Divide in Iraq; ISIS; U.S.-Iraq Relations; The U.S. War in Iraq; The Sunni-Shi'i Divide; the Alawites and Syria; U.S.-Iranian Relations; and Turkey’s Politics.

And Read these great articles on women around the world: Women and American Politics; Domestic Violence; Women’s Struggles in Zimbabwe; and Women’s Rights in Afghanistan.

Listen to these History Talk podcasts on Understanding the Middle East; the Syrian Civil War and Arab Spring; Violence against Women; and Reproductive Rights and Reproductive Justice.

From 2011 to 2014, breathtaking political changes transformed the lives of men and women in Egypt.

First, with the slogan “bread, freedom and social justice,” the Egyptian Revolution of 2011 brought together a wide range of constituencies to protest the three-decade-old regime of Hosni Mubarak (PDF File) and its authoritarian politics and repression.

In a mere 18 days, Egyptians—women and men, young and old, Christian and Muslim, secular, Islamic and Islamist—overthrew Mubarak and dismembered his National Democratic Party (NDP). The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF), a transitional military regime, assumed executive power for eighteen months after Mubarak fell on February 11, 2012).

Then, in the parliamentary elections that followed, the Freedom and Justice Party (FJP)—the Muslim Brotherhood’s political arm—and its presidential candidate, Mohamed Morsi won about 10 million votes, or 40 percent. The more conservative Islamist Salafis also had a strong showing, winning more than 7 million votes, giving the Islamists control of almost two-thirds of the seats in parliament.

Morsi was the winner of Egypt’s first competitive presidential election, but his government was short-lived. He issued a constitutional decree in November 2012 that gave him broad legislative and executive powers so he could hasten the passage of a new constitution. Many Egyptians criticized his government for its inability and unwillingness to form coalitions or to address the basic tensions in Egypt: between Islamists and secularists, between democrats and authoritarians, and between civilians and the military.

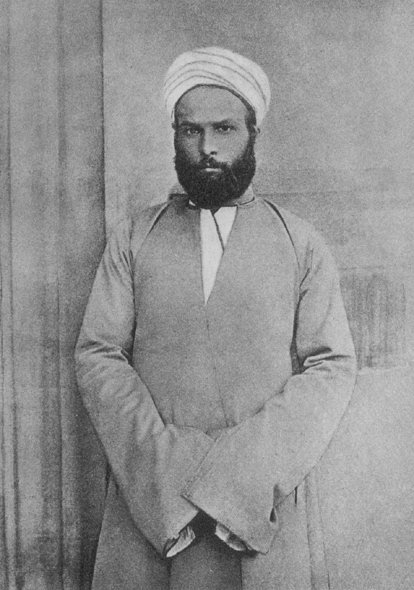

Hosni Mubarak (left) and Mohamed Morsi (right).

Millions of Egyptians participated in demonstrations demanding Morsi’s ouster. These protests exceeded the size of those against Mubarak in 2011, and culminated in a military coup d’état led by General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in July 2013.

An Egyptian criminal court then outlawed the Muslim Brotherhood and banned all the activities it organized, sponsored, or financed. In March 2014, in the largest mass trial in the history of Egypt, the court sentenced 529 members of the Brotherhood to death. El-Sisi consolidated his power and was sworn in as president on June 8, 2014.

|

Women were actively involved in all these events and many saw the turmoil as a hopeful opportunity to redefine their place in Egyptian society. New forms of women’s rights activism emerged during the revolution, taking the debate over gender relations in new directions and building broader partnerships of women and women’s organizations.

However, this recent female activism has roots in a longer tradition of debates about feminism in Egypt and is part of a historical process in which Egyptian feminists participated in grassroots movements to confront the Egyptian patriarchy.

During the revolution that began in 2011, Egyptian women featured in the international media primarily as victims. Women were sexually assaulted in Tahrir Square and women arrested for participating in protests were subjected to degrading “virginity tests.”

But popular mobilization against these abuses also fueled collaboration among women’s organizations, uniting them under the larger revolutionary call for dignity, freedom, and justice.

On February 24, 2011, one such alliance came together to protect and support women. Called the Coalition of Feminist Organizations in Egypt, it was composed of 16 groups, including New Woman Foundation, Women and Memory Forum, Center of Egyptian Women Legal Aid, Women’s Forum for Development, Alliance of Arab Women, Egyptian Association for Family Development, and “Nazra” Association for Feminist Studies.

The coalition was effective in organizing against the cases of mob sexual assault and gang rape in Tahrir Square and the forced virginity tests on female detainees.

The Nazra Association for Feminist Studies, for example, documented around 500 cases of sexual assault from 2012 to 2014 during the protests. There is no statistical information about the number of detainees subjected to infamous virginity tests. El-Sisi, then the head of the Egyptian Armed Forces, defended these procedures unconvincingly on the ground that the tests were routine and the procedure was carried out “to protect the girls from rape, as well as to protect the soldiers and officers from rape accusation.”

The coalition brought together different anti-sexual harassment support groups such as OpAntiSH (Operation Anti-Sexual Harassment/Assault) and Tahrir Bodyguard, and other initiatives such as “The Daughters of Egypt are a Red Line,” Harass-map, and Shoft Taharosh(“I Saw Harassment”). Together, these support groups organized rescue teams, provided medical and psychological support to victims, and raised public awareness. They have also demanded investigation, prosecution, and fair trial of the crimes of sexual harassment and assault cases during the 2011-2014 demonstrations.

More broadly, the coalition endorsed and supported the demands of the January 25 revolution and called for the full participation of women in all efforts related to getting rid of the Mubarak regime, including its institutions and symbols.

The coalition set itself against the “state-sponsored” feminism represented by the National Council of Women (NCW) founded by a Mubarak presidential decree in 2000 and consequently led by his wife, Suzanne.

The NCW actually had progressive gender policies. These include empowering women in rural areas and facilitating the acquisition of identity cards, collecting data on illiteracy among women, providing information about health services and disease prevention, and important legislation proposing changes to the Personal Status Code, granting women the right to Khul’ (a relatively quick, unilateral, irrevocable, “no-fault” divorce) provided that a woman relinquishes all her financial claims on her husband.

Although state feminism and the first lady’s patronage had produced some successes, the coalition declared the NCW illegitimate because it had not denounced the violence perpetrated against the Egyptian people during the 2011 revolution. The coalition derided NCW legislation as “Suzanne’s laws.”

Consequently, the leading women’s rights groups articulated clear demands for the replacement of NCW with a more “transparent, democratic body of representatives” to represent Egyptian women at the local, national and international levels, outside of state control. Under pressure, the NCW replaced those of its members who were closely associated with the Mubarak regime with new ones as a moderate response to those criticisms.

Roots of the Egyptian Feminist Movement: Islamic Modernism

Egyptian feminism emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as part of several other intellectual currents swirling in the region. These included tensions between Islamic modernism and traditionalism, between Egyptian nationalism and pan-Arabism, and between Islamism and secularism.

Feminist consciousness was grounded in the framework of Islamic modernism. Muhammad ‘Abduh (1849-1905), the Grand Mufti of Egypt and a vigorous disciple of Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani, was one of the most systematic advocates of Islamic reform.

|

Influenced by Herbert Spencer, Leo Tolstoy, and Auguste Comte, ‘Abduh advocated for a comprehensive educational reform program at Al-Azhar (one of the world's oldest educational institutions), harmonizing faith and reason, European ideals with Islamic concepts, and creating what historian Indira Falk Gesink has called “a hybridized framework for an authentically Islamic revolution of thought,”

‘Abduh advocated abandoning taqlid (imitation, conformity to legal precedent, traditional behavior, and doctrines), and returning to the practice of ijtihad (independent inquiry and free exercise of reason) in matters of personal belief. For issues outside of personal belief, such as the law, he never intended the practice of ijtihad to be used by ordinary people. Like al-Afghani, he advocated reform of Islam from above, without splitting the community.

However, modernist pro-ijtihad reformers, including some contemporary women’s rights activists, “gave ijtihad a social definition and enlarged its franchise by encouraging laymen to proceed directly to primary sacred texts of their religion for guidance,” in Gesink’s words.

Feminist writing gradually developed within this modernist Islamist discourse. Heavily influenced by ‘Abduh, Qasim Amin employed modernist arguments for gender reform in issues like ending facial veiling, seclusion, abuses of divorce, and polygamy.

Amin published the famous Tahrir al-Mar’ah (“The Liberation of Women”) in 1899, and al-Mar’ah al-Jadidah (“The New Woman”) in 1900. Both ‘Abduh and Amin stressed the superiority of Western ways and advocated raising the level of education of Egyptian women to that of their European counterparts.

|

Feminist consciousness was first articulated among middle- and upper-class women. A’ishah al-Taymuriyah (1840–1902) and Zainab al-Fawwaz (1860-1914) were among the pioneers who confronted women’s domestic seclusion. Hind Nawfal inaugurated a separate women’s press (written by women and about women’s issues) in 1892, when she founded al-Fatah (The Young Girl). Authors Malak Hifni Nassif (1886-1918) (writing under the pseudonym Bahithat al-Badiya), Nabawiyya Musa (1886-1951), Huda Sha’rawi (1879-1947), and Mayy Ziyadah (1886-1941) advocated public female roles, with women to repudiate domestic confinement, “unveil, and work in various professions.”

The goals of most women’s organizations in Egypt were charitable and educational. Egyptian women pioneered philanthropic activities and social welfare as a way out of domestic seclusion and became teachers and administrators in the state education system.

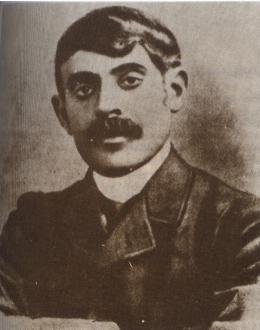

A cartoon from Al-Kashkul (Scrapbook), 1924. Women in burqa walk by and mention that they do not want freedom, if freedom means dressing like the women in swimsuits. (Photo by Gulsah Torunoglu, American University in Cairo Library)

Some combined these activities with efforts for greater gender equality, like Jam’iyat al-Mar’ah al-Jadidah (The New Woman Society), al-Ittihad al-Nisa’I al-Tahdhibi (Women’s Refinement Union), Jam’iyat al-Raqy al-Adabiyah li-al-Sayyidat al-Misriyat (Ladies Literary Improvement Society), and Jam’iyat al-Nahdah al-Nisa’iyah (Society of Woman’s Awakening).Not all women’s organizations agreed on the proper role for women in Egyptian society or what gender relations should be.

Other, more conservative organizations idealized the constructed social roles for women and invented a “cult of domesticity.” These include Fatma Rashid’s Jam’iyat Tarqiyat al-Mar’ah (“Society for the Advancement of the Women”) and the Jam’iyat Ta’lim al-Banat al-Islamiyah (“The Islamic Society for the Education of Girls”).

The Colonial Encounter and the Egyptian Feminist Union

The ideological situation grew more complex when Islamic modernism intertwined with anti-colonialism, nationalism, and anti-imperialism.

The “colonial encounter” with Europe in the late 19th century profoundly altered the discourses and practices setting gender boundaries in the Middle East. Anti-colonialism and nationalism shaped the ways Egyptian women formulated the ideological bases of their activism.

In Egypt, nationalism fostered feminist solidarities. In turn, Egyptian women generated a nationalist discourse that legitimized their case. Nationalists and feminists collaborated to pursue their common goal of gaining independence from a colonial power. Growing Arab nationalism, especially after the 1950s, fostered pan-Arab feminist movements.

After the end of the First World War, during the major nationalist struggle known as the Revolution of 1919, Egyptians demanded an end to the British protectorate. Women’s groups attended nationalist protests. Women founded their first formal political organization in 1920, the Wafdist Women's Central Committee (WWCC), attached to the popular nationalist-liberal Wafd Party. The WWCC organized anti-British economic boycotts and coordinated support for the Wafd Party.

Women also expressed themselves through other means. They contributed to the women’s press, sponsored lectures and cultural events, and gave women a greater and more organized public presence. Their efforts in health, education, and job promotion encouraged governments to do more in these fields.

A more radical development of liberal feminism began with the Egyptian Feminist Union (EFU) in 1923, headed by a pioneering Egyptian feminist, Huda Sha’rawi. The EFU was the first formal feminist organization in Egypt and was part of the international organized feminist movement from the beginning.

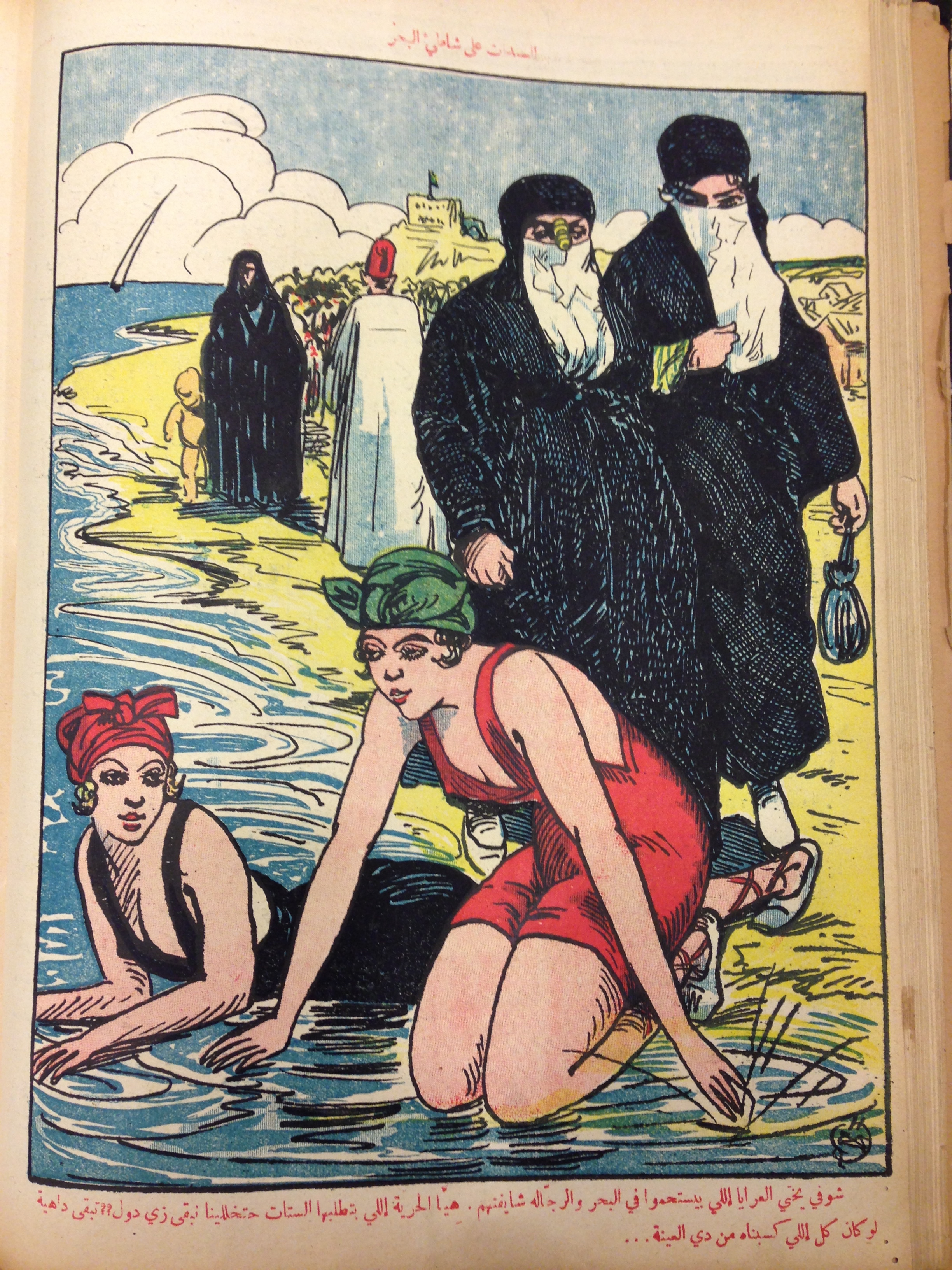

The Egyptian Feminist Union published two important periodicals: L'Egyptienne (“The Egyptian Woman”), the first feminist journal in French aimed at an international feminist community; and Al-Mısriyah (also “The Egyptian Woman”), the bi-monthly Arabic journal promoting solidarity among different classes and communities of Egyptians.

|

The EFU campaigned for gender equality in education, woman’s suffrage, and reform of the personal status laws, marriage age, polygamy, divorce rights, and state-regulated prostitution.

Egyptian women’s organizations in general, and EFU in particular, brought significant changes in women’s employment, health, education, social services, philanthropic activities, and public roles. Their influence was more limited, however, in reforming the laws directly affecting women. The electoral law of the 1923 Constitution restricted voting and political office to men, and the Personal Status Code did not change.

The EFU shied away from openly challenging religiously ordained issues, and instead sought Islam’s legitimizing force in its agenda. Their critique of the family law was moderate, if not conservative. The EFU never “deviated from insistence upon reform within the framework of Islamic religious law, the Shari’ah,” or approved the secular family code Turkey adopted in 1926. The organization did not challenge the conventional gender roles, but instead “adhered to the mainstream view that women’s and men’s family roles were ordained by religion,” in the analysis of historian Margot Badran.

Ottoman Propoganda Poster in the “Cairo Punch,” al-Siyasa al-Musawwara, “Happy are the Free!!! Occupation in Arab countries and in Egypt, and other countries which are not occupied by the British and French.” Signed, First Egyptian Cartoonist, ‘Abd al-Hamid Zaki. (Photo by Gulsah Torunoglu, Egyptian National Archives, Cairo)

This was a wise strategic choice that prolonged the EFU’s lifespan and gradually consolidated women’s infiltration into the public sphere through philanthropic associations and voluntary social service. But this moderate feminism did not ease patriarchal pressures on women. Woman’s suffrage and eligibility for election had to wait until 1956.

On another front, Muslim Women’s Society (WMS), founded in 1936 by former EFU member Zainab Al Ghazali, and the Association of the Egyptian Woman’s Awakening also defined women’s liberation within an Islamic framework, and they sided with the Ikhwan Muslimin (Muslim Brotherhood) founded by Hasan al-Banna in 1928.

Pan-Arab Feminism

During the 1930s and 1940s, Islamic modernism intertwined with the discourse of Arabism, creating a new form of solidarity with the Palestine cause in the region. The pan-Arab feminist movement had origins partly in the Palestinian national struggle. This new form of feminism emerged as a regional alternative to the international feminist movement, of which the Egyptian feminist movement was part.

The EFU played a prominent role in the institutionalization of pan-Arab feminism at a time when international feminism was disintegrating, or so it seemed. Cracks in global feminism became clear when the International Alliance of Women (IAW) refrained from advancing a colonial critique of the lack of social justice in British-ruled Palestine. The Arab Feminist Union (AFU) was founded in 1944 and Huda Sha’rawi was selected as president.

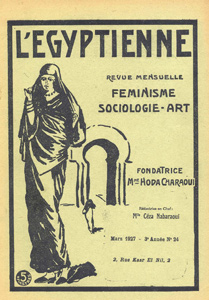

Cartoon of Huda Hanim Sha’rawi and Safiyya Hanim Zaghlul chased by Egyptian policemen, in Al-Kashkul (Scrapbook) May 22, 1931. When Huda Sha’rawi calls Safiyya Zaghlul, “mother,” Zaghlul replies, she is not her mother, and that she is not even the mother of the generation of her children, satirizing the use of maternal nationalist rhetoric, as in “mother of the Egyptians.” (Photo by Gulsah Torunoglu, American University in Cairo Library) |

The convention of the Arab Feminist Congress and the formation of the AFU aimed at consolidating a collective vision among Arab countries while promoting their unified involvement in the international feminist movement.

A decade after the consolidation of Arab feminism, in the aftermath of the revolution of the 1952, the state dismantled the EFU in 1956. The EFU has continued its activities to this day as a social welfare society under the name Huda Sha’rawi Association. In 2011, the Arab Alliance for Women (AAW) led by Hoda Badran revived the EFU, but its effects remain to be seen.

Feminism under Nasser, Sadat, and Mubarak

While the British Protectorate was dissolved in 1922, the British continued to control and occupy Egypt until the revolution of 1952. In the wake of that event Gamal ‘Abdel-Nasser became first prime minister and then president of Egypt, a position he would hold from 1956 to 1970.

Some scholars and activists regard Nasser’s regime as a “golden era” for the advancement of women’s rights. Under Nasser, the 1956 Constitution and the new electoral law granted women the right to vote and the right to run for public office.

“Preventing Women the Right to Vote”The Military: “Go back to your homes … leave politics to men.” Date and Source Unknown. (Photo by Gulsah Torunoglu, Huda Sha’rawi Library, Cairo)

Like several other modernizing nationalists, such as Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in Turkey, Nasser encouraged women to work outside the home for wages and offered women greater educational opportunities. The number of girls enrolled in primary and high schools rose rapidly, and women’s literacy rate increased. At the same time, Nasser’s regime promulgated new progressive labor laws, expanded women’s rights, and offered extended legal protections for working women (such as paid maternity leave, accessible childcare services, and affordable, state health care).

Nasser’s 1962 socialist Charter for National Action endorsed gender equality. It stated: “Woman must be made equal to man and she must therefore shed the remaining shackles that impede her free movement, so that she may play a constructive and profoundly important part in shaping the life of the country.” The charter also established a progressive agenda by approving, at least in principle, “birth control and family planning,” though with goals of economic development as the primary motivating force rather than an informed feminist program.

Although the state proclaimed important public advances for women, it did not question the patriarchal structure of Egyptian society institutionalized by the Personal Status Laws of the 1920s and 1930s. Gender relations at home remained unchallenged.

Fearing any autonomous political activity and non-governmental initiatives, the state suppressed all forms of independent politics, including major feminist organizations and radical Islamists.

It dismantled the Egyptian Feminist Union, but allowed it to exist as a small social welfare society under the name of the Huda Sha’rawi Association. Duriyya Shafiq’s Bint al Nil (“Daughters of the Nile”) Party was also closed down, and she was placed under house arrest. Others like Inji Aflatoun, for her association with the Communist Party, and Zainab al-Ghazali, head of the Muslim Women’s Society, were imprisoned.

Overall, state-sponsored feminism during the Nasser regime offered greater educational and employment opportunities, but, as scholar Selma Botman cautions, “gender-specific objectives remained outside the core of the revolutionary ideology.”

By the time that Anwar Sadat came to power in 1970, women had gained more public presence and intellectual, social, and professional experience to continue their activism under Sadat’s rule and during the regime of Mubarak.

Initially, Sadat consolidated his presidential power by suppressing Nasserites and secular leftists, and cooperated with the Islamists to do so. This alliance led to an increasing Islamist revival, which had serious complications for women and the secular democrats.

In a major setback for women, Sadat’s 1971 Constitution reversed women’s statutory equality guaranteed under the Nasser regime, and allowed gender equality only if it did not undermine the rules of Shari’ah law.

The 1971 Constitution stated: “The state guarantees a balance and accord between a woman’s duties towards her family, on the one hand, and towards her work in society and her equality with man in the political, social, and cultural spheres, on the other, without violating the laws of the Islamic Shari’ah.” Moreover, Sadat amended the Constitution in 1976 to make Islamic jurisprudence the principal source of legislation.

In the later 1970s, however, Sadat began to encourage women’s rights, in part for reasons of international relations. Sadat’s infitah (“open door”) policies, rapprochement with the United States, his strong pro-Western rhetoric, and continuous struggle to foster a global reputation as a Westernizer and modernizer, all played a role in his support of women’s rights.

The UN Decade of Women (1975-1985), pressure from Egyptian and international feminist groups, and advocacy of women’s rights by Sadat’s wife, Jihan Sadat, also induced the regime to promote gender issues. Sadat established the Egyptian Women’s Organization and the National Commission for Women to handle family planning, illiteracy, and child welfare.

|

At the same time Jihan, set up women’s welfare organizations and initiated a series of reforms, known as “Jihan’s law,” granting women legal rights in marriage, polygamy, divorce, and child custody.

This Personal Status Law of 1979 was implemented by a presidential decree when parliament was in recess and was short-lived. Facing strong opposition from the Islamists—who condemned it as Western-oriented and un-Islamic—and some nationalist leftists—who argued that it was passed unconstitutionally by Sadat—the Law was nullified by the Constitutional Court in 1985.

Despite the progressive laws of 1979, the state did not encourage independent feminist activism under Sadat’s regime. In September 1981, Dr. Nawal al-Saadawi—a medical doctor and a prominent feminist author, whose writings, including her famous book al-Mar’ah wa Al-Jins (“Women and Sex,” 1971), were censored by the state—was arrested and jailed for months.

Sadat was assassinated by a member of a militant Islamist group the same year, and was succeeded by Vice President Hosni Mubarak.

Under President Mubarak, gender-studies scholar Nadje Al-Ali finds that there was an “increased confrontation with the Islamists over the implementation of the Shari’ah law,” pressuring the Mubarak regime to “legislate and implement more conservative laws and policies toward women and to diminish support for women’s political representation.” As more conservative and fundamentalist voices gained importance, Mubarak canceled the Personal Status Law of 1979 and abolished the reformed laws under Sadat.

During early 1980s, there was a renewed visibility and organisation of independent feminism pluralized by competing discourses. The Arab Women’s Solidarity Association (AWSA) was founded by al-Saadawi during this period. AWSA held its first conference in 1986, with the slogan “unveiling the mind,” and organized a number of cultural seminars about women. AWSA was outspokenly critical about Islamist positions on gender.

At the same time, there were increasing numbers of Islamist women activists like Zainab al-Ghazali, Safinaz Qazim, and later, Heba Rauf Ezzat, who promoted traditional gender roles that buttressed the virtues of motherhood and the family. These competing discourses on the “women’s question” politicized under the Nasser and Mubarak regimes, gradually resulting in a proliferation of feminist politics in Egypt.

Finally, under Mubarak, the National Council of Women (NCW), a governmental body to advance women’s status, was formed in 2000 and an NGO law was passed giving the Ministry of Social Affairs the power to dissolve NGOs.

Egyptian Feminism: Current Debates

The tension between Islamic and secular versions of feminism remains thorny for Egyptian women. Marwa Sharafeldin, who is a board member in Musawah, the international movement for Muslim family law reform, and the co-founder of the Network of Women's Rights Organizations in Egypt, points to disagreements over basic frames of reference among different feminist organizations in Egypt.

As mainstream Egyptian feminists attempt to reform the Personal Status Law, should they take human rights and/or non-religious humanism as a point of reference or should they take Islam as a point of reference? According to Sharafeldin, the compromise is usually a combination of human rights and “enlightened” interpretations of religion. There is no reference to what “enlightened” means, but NGOs take it as meaning “gender-sensitive Islamic interpretations.”.

Some Egyptian feminists, like Omaima Abou-Bakr, advocate exploring the possibilities within Islam, and others suggest that the very act of rereading the Qur’an gives women an opportunity to deploy religious texts in defense of their rights, and allows them to derive agency and strength from within the Islamic tradition.

As proponents of modernist Islam and its natural extension, “Islamic feminism,” Islamic feminists consider it a powerful alternative to secularist feminism, the form most likely to succeed in Egypt.

Secular-oriented women’s organizations in Egypt argue vehemently against operating within an Islamic framework, which they believe would “either consciously or unwittingly delegitimize secular trends and social forces.” These feminists argue that religious doctrine should not be the basis of laws, policies, and institutions.

According to secular feminists, as long as religiously inspired feminists remain focused on theological arguments rather than socioeconomic and political questions, and as long as their point of reference is the Qur’an rather than universal standards of human rights, their impact will be limited, and their strategy will reinforce the legitimacy of the Islamic system. In the end, secularists argue, Islamic feminism will only make superficial changes for women, and will not adequately confront patriarchal power.

The Coalition of Egyptian Feminist Organizations (2011) provided a platform for women’s feminist organizations to reflect upon these competing discourses. Despite all appearances of consensus, centuries-old debates remain to be solved. Coalitions among feminist organizations are too often held to unrealistic expectations. They cannot be understood without recognizing their limits.

Debates among Egyptian feminists today reflect some of the unresolved issues that first arose more than a century ago. Questions about whether feminism ought to be religiously rooted and grounded in secular ideas—and the extent to which Egyptian women face particular issues or share their struggles with women throughout the Arab region and around the world—remain as pressing as they were when Egyptian women first raised their voices for change. They became yet more urgent in the revolutionary years of 2011-14.

Books and Articles:

Ahmed, Leila, Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate, New Haven, 1992

Badran, Margot, Feminists, Islam, and Nation: Gender and the Making of Modern Egypt, Princeton, 1995

_____, Feminism in Islam: Secular and Religious Convergences, One World Publications, 2009.

Baron, Beth, Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2005

_____, The Women’s Awakening in Egypt: Culture, Society and the Press, New Haven, 1994

Booth, Marilyn, May Her Likes be Multiplied: Biography and Gender Politics in Egypt, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2001

_____, Classes of ladies of cloistered spaces writing feminist history through biography in fin de siècle Egypt, Edinburgh University Press, 2015.

Botman, Selma, Engendering Citizenship in Egypt, Columbia University Press, 1999.

Hatem, Mervat, “The Enduring Alliance of Nationalism and Patriarchy in Muslim Personal Status Laws: The Case of Modern Egypt,” Feminist Issues 6 (1): 19-43, 1986.

Karam, Azza: Women, Islamisms and the State: contemporary feminisms in Egypt, Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998.

Laura Bier, Revolutionary Womanhood: Feminisms, Modernity, and the State in Nasser's Egypt, Stanford, 2011.

McLarney, Ellen Anne, Soft Force: Women in Egypt's Islamic Awakening (Princeton Studies in Muslim Politics), Princeton University Press, 2005.

Mahmood, Saba, Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject, Princeton, 2011

Nadje Al-Ali, Secularism, Gender and the State in the Middle East: The Egyptian Women's Movement (Cambridge Middle East Studies), 2000.

Nelson, Cynthia, Doria Shafik, Egyptian Feminist: A Woman Apart, University Press of Florida, 1996.

Nikki R. Keddie and Beth Baron eds, Women in Middle Eastern History: Shifting Boundaries in Sex and Gender, 1993.

Pollard, Lisa, Nurturing the Nation: The Family Politics of Modernizing, Colonizing, and Liberating Egypt, 1805-1923, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2005

Tucker, Judith E., Arab Women: Old Boundaries, New Frontiers, Bloomington.

Tucker, Judith E., Women in Nineteenth-Century Egypt (Cambridge Middle East Library)

Online resources:

SSRC

https://items.ssrc.org/tag/egypt/

Ottoman History Podcast

http://www.ottomanhistorypodcast.com/2014/11/law-crime-ottoman-egypt-fahmy.html

Nazra Association for Women

Harassmap

Women and Memory Forum (WMF)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IEpwjtwLYng

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-PRplz7BF6w

Feminism Inshallah

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B1Vrt6E8EYM

Behind the Wheel: Women Drivers in Egypt

https://www.aljazeera.com/program/al-jazeera-world/2016/2/25/behind-the-wheel-egypts-women-drivers

The Square – Meidan Tahrir

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bvVvDYv-4AM

The Death of Gamal Abdel Nasser

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t3JOFyQFE6M

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkhnhGmfKR0

The "Qanun Nashaz" Campaign, under the motto "behind every abused Woman, there is a Law", was launched on November 25, 2014 by Nazra For Feminist Studies and the Center For Egyptian Women's Legal Assistance (CEWLA) as a part of their contribution to the annual 16-day Campaign for the Elimination of Violence against Women, which ends on the 10th of December, in conjunction with International Human Rights Day. The "Qanun Nashaz" Campaign tackles all the legal issues which legitimize violent practices against women, in both public and private spheres.