As this August 1976 cover from Ms. Magazine reminds us, it is only recently that domestic abuse was identified as a serious, public social problem.

Amidst the cascade of high-profile cases of domestic abuse in the recent past, it is easy to forget that, not too long ago, Americans didn't view domestic abuse as a problem worth talking about. Men battered women, but this happened in the privacy of home and within the intimate confines of marriage. As a result, police and policymakers looked the other way and women were intimidated into silence. Through the work of feminist activists, as historian Peggy Solic explains this month, something that was once considered acceptable and private has become unacceptable and public.

Read more from Origins: Same-Sex Marriage; The Real Marriage Revolution; Women's Rights in Afghanistan; Women’s Struggles in Zimbabwe

Listen more: Violence Against Women; Same-Sex Marriage; Abortion in Europe and America; Policing in America

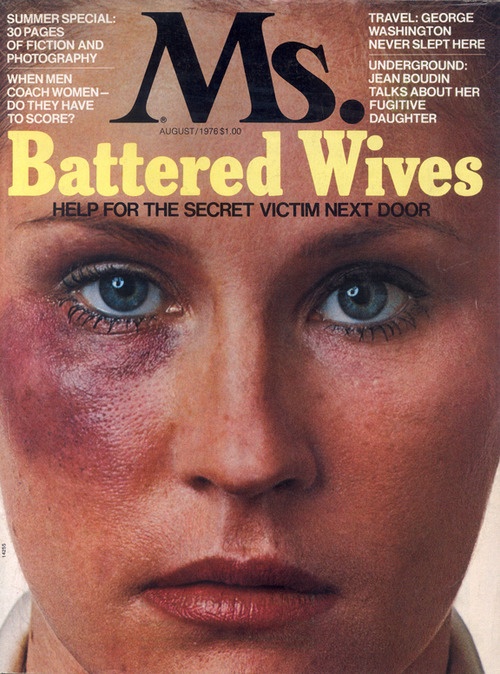

On February 15, 2014, NFL star Ray Rice and Janay Palmer, who were then engaged, were both arrested on assault charges in Atlantic City after getting into what Rice’s attorney then described as a “minor physical altercation” in an elevator.

A few days later, TMZ released a video showing Rice dragging an unconscious Palmer out of the hotel elevator. Rice was indicted on third degree aggravated assault charges, to which he pled not guilty. He was accepted into a pretrial intervention program, which is rarely used in domestic assault cases, for first-time offenders that would clear him of all charges in six months.

|

| TMZ released the video (screenshot left) of Ray Rice dragging his unconscious fiancé from the elevator. (Photo Credit, AP) |

In late July 2014, NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell also handed Rice a two game suspension. Many felt that the punishment was too light, and it incited criticism of the NFL’s personal conduct policy on domestic violence. In response, the NFL revised its policy and instituted a six game suspension for first time offenders.

Controversy around the incident, however, erupted again in early September 2014, when TMZ released another video, this one of the fight that occurred in the elevator. It showed Rice punching Palmer and knocking her to the ground.

Goodell, having already faced criticism for punishing Rice too lightly, tried to argue that he had never seen that particular footage and that Rice had misrepresented the incident to him. He suspended Rice indefinitely. When Rice appealed his suspension this past November, however, a judge ruled that Rice had not lied or misled the NFL about what happened in the elevator. His suspension was lifted.

The fact that there was public outrage not only over Ray Rice’s transgressions, but also the NFL’s handling of those transgressions, reflects important changes in public and legal reactions regarding violence towards women.

These public acts confirm that the extensive work that feminist activists and battered women themselves did in the 1970s has been, in some measure, successful in changing policies and attitudes about domestic violence.

These activists made domestic violence visible, defined it as a significant social issue, and demanded that those in positions of power impose consequences on abusers.

They argued that domestic violence was, like rape, a problem rooted in the abuse of power and it was perpetuated because it had never been seen as a problem in the first place. They highlighted police departments’ policies of looking the other way when men beat women and a social-service system ill-equipped to deal with battered women.

Feminist activists in the 1970s responded in two broad ways.

First, they established shelters for victims, often organized, funded, and run outside of the existing social-service system. These became places where women could not only find immediate help but also change their domestic situation.

Second, activists fought for the adoption of mandatory arrest policies, which require police to arrest a perpetrator when there is probable cause to believe that a domestic assault has occurred.

Despite the radical transformation in how we view domestic violence that has characterized recent years, the process has been anything but straightforward.

Among many hurdles, activists for years have struggled over where the boundaries of public and private are found in family life. And this distinction has been crucial to how American law and police approach violence within the family.

Those concerned with domestic violence have consistently grappled with the question of what kind of violations necessitated public scrutiny and intervention in a marriage or family, otherwise private institutions.

Invoking a right to privacy in the family has historically served to shield domestic abusers from consequences, as well as to naturalize the home as a place in which some violence is socially acceptable.

Legislating Against Domestic Violence in the New England Colonies

Of course, feminists of the 1970s were not the first activists to address domestic violence. In 1641, the Massachusetts Bay colony passed a law making spousal abuse illegal. These Puritans also relied heavily on community policing to regulate violence in the home.

Privacy was not a paramount concern to the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony of the seventeenth century. The success of their New World endeavor—their “city on a hill”—rested on the creation of a community that was peaceful, stable, and godly.

Family violence was one of the many sins that had the potential to rupture the stability of their desired community. It put both the individual’s and the community’s relationship with God in jeopardy, and could therefore threaten the success of the entire project.

“In Puritan society, meddling was a positive virtue,” historian Elizabeth Pleck argues. Community policing, moral shaming, and nosiness were among the primary ways in which the Puritans dealt with domestic abuse.

They saw husbands who beat their wives without reason as violating the bonds of matrimony, and these men were dishonored in the eyes of the community.

Puritans never went so far as to argue that violating those bonds of matrimony, at least by husbands, justified the dissolution of marriages. They believed in preserving the family unit above protecting the physical safety of victims, and so Puritan courts were reluctant to separate wives from husbands.

Sometimes they would allow wives to live separately from husbands, but only until the husband was “reformed.” Most often, perpetrators of family violence were sentenced to pay a fine or to be whipped.

Puritans did believe that some violence in the home was justified.

Because they believed so strongly in hierarchy and authority, Puritans also thought that wives could provoke violence. For example, wives who “nagged” their husbands too much, neglected their families, or committed adultery were not seen as blameless victims if their husbands hit them.

So, although the Massachusetts Body of Liberties (1641) included a provision that stated, “Everie marryed woeman shall be free from bodilie correction or stripes by her husband, unless it be in his owne defence upon her assault,” it also provided for the use of “legitimate” force in the home.

Husbands, as head of households and therefore the closest to God, could use physical violence to punish disobedient wives, children, or servants. In Puritan society and law, wives, children and servants did not have the authority to justify violence against male heads of households.

Legislating against domestic violence made the Puritans unique in their time. Most other communities accepted family violence as normal, acceptable, and even necessary to the good functioning of society.

The Puritans’ motivations for opposing spousal violence came from their distinctive project in the New World, and not out of an altruistic concern for wives who were abused. Their insistence on upholding the hierarchy of the patriarchal family and the authority of husbands would profoundly influence the way domestic violence was perceived.

The belief that some violence in the home, especially violence that was meant to control “disobedient” wives, was acceptable persisted.

This idea, combined with the later Victorian belief that the home was the ultimate pillar upholding personal privacy in the 1800s, made it difficult for 19th century women activists to question these power relationships at the heart of the male-dominated family. Instead, in order to address domestic violence, Victorian activists would have to tackle alcohol consumption first.

Temperance Activists take on Domestic Violence:

Roughly 200 years after the Puritans established the Body of Liberties, temperance reformers became the first American activists to consider domestic violence a serious social problem.

The earliest temperance society can be traced to the 1830s and aimed to prohibit the sale, production, and distribution of alcohol. Men controlled this early organization, but by the 1840s the movement had been taken over by white, middle-class women.

These women believed that drinking excessively led to spousal abuse, and sought to eliminate the source of the problem.

Alcohol consumption in the nineteenth century was indeed prodigious. According to scholar Daniel Okrent, in the 1830s American adults consumed seven gallons of pure alcohol every year. Okrent says, “[F]iguring per capita, multiply the amount Americans drink today by three and you’ll have an idea of what much of the nineteenth century was like.”

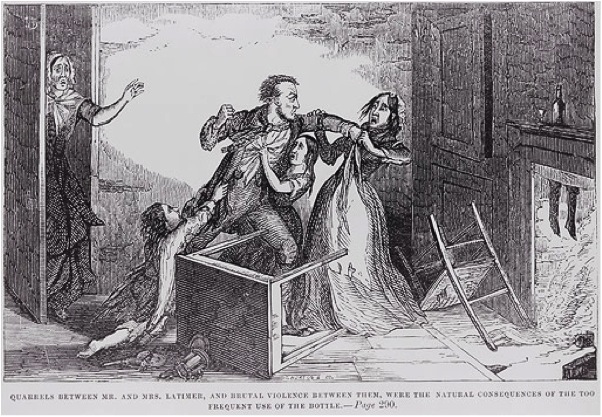

|

| "Quarrels between Mr. and Mrs. Latimer, and brutal violence between them, were the natural consequences of the too frequent use of the bottle," reads this illustration from the temperance era. |

Many temperance activists believed that wife-beating was a byproduct of drunkenness and historical evidence suggests they were not wrong.

Some feminists in the movement took the argument further by insisting that it was also a gendered problem, enacted on women by men. Women like Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Amelia Bloomer—who was most famous for creating the Bloomer costume—campaigned for the liberalization of divorce laws as the logical extension of the temperance movement and its equation of drink with domestic violence.

These antebellum feminists argued that changes to divorce practice were a moral necessity. They considered it a cruel perversion of marriage and motherhood to require a woman to remain married to a husband who was made “brutish” by alcohol.

By 1850, some states granted divorce on the grounds of cruelty, which was vaguely defined, but battered women were dependent on the mercy and judgment of individual judges.

Stanton, Anthony, and Bloomer sought legal changes that would allow women to divorce their husbands on the grounds of drunkenness as well. While these changes would not have directly addressed the issue of domestic violence, advocates hoped that they would expand women’s access to divorce and allow them to more easily call on state intervention in their marriages.

Most American women, however, were not supportive of the campaign to liberalize divorce laws.

The 250,000 women who belonged to the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), one of the largest women’s reform organizations of the nineteenth century, remained focused on their goal to prohibit the sale and consumption of alcohol, assuming related social problems would disappear as a result.

Frustrated by a lack of support for their crusade to expand divorce laws, Stanton and Anthony both resigned from the New York State Temperance Society in 1853. Although they continued their campaign to change divorce laws, neither one ever joined another temperance society again.

While they did not endorse strategies such as liberalizing divorce and child custody laws for abused women, the women of the WCTU did seek to redefine the patriarchal family as one in which women held the power to reform abusive husbands.

These reformers believed that the home was a place where women held moral authority and could potentially (as the Puritans thought) shame their husbands into behaving themselves.

|

| Frances Willard |

When Frances Willard, president of the WCTU from 1879 to 1898, died, both the WCTU’s influence and the focus on women’s issues in the fight for prohibition began to wane. This was partly due to Willard’s death and partly due to the rising popularity of the Anti-Saloon League (ASL), which took up the campaign until the passage of prohibition.

Although the battered wife who populated the WCTU’s literature and rhetoric would not completely disappear from the campaign, she was no longer its central figure.

After the Constitutional amendment barring the production, transport, and sale of alcohol took effect in 1920, domestic violence almost completely disappeared from public consciousness.

As Elizabeth Pleck says, “There was virtually no public discussion of wife beating from the turn of the century until the mid-1970s.”

For most of the twentieth century, social workers concerned with domestic matters focused on poor, immigrant, or African American households. They blamed individual failings for the violence they found in these households and concentrated primarily on abuse of children.

If alcohol had been considered a root cause of family violence during the temperance era, then it was poverty, the cultures of immigrants, and racial and ethnic differences that were seen as the sources of wife beating in the decades that followed.

Domestic violence would not again be connected to a social movement until the 1970s with the emergence of a new generation of feminists. And with them came a new idea: that violence in the family was the result of a systemic assault on women by men.

Feminists in the 1970s Take on Domestic Violence:

In 1976, a Washington Post headline announced “Home Called More Violent than Street.”

The story covered a conference of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, in which a panel of criminologists declared, “the problem [of domestic violence] is worse than crime on the streets.”

The panel attributed part of the problem to the “reluctance of the police, the courts, and the government to pass and enforce laws that intrude on the family.” American notions of the need to protect the individual from state intrusion, and of the paramount importance of privacy, prevented leaders and victims in the United States from confronting domestic abuse.

In the 1970s, feminists “rediscovered” domestic violence and defined it as a serious social problem.

This was only possible because the women’s movement of that era inspired women to look inward and think critically about their most personal and private relationships. It also encouraged women and men to question the nature of the patriarchal family.

Feminists argued that sexual harassment, rape, domestic violence, and all kinds of sexual violence were not a natural part of family life and that they result from an abuse of power rather than a gratification of sexual needs.

One of the ways in which feminists came to this analysis of domestic violence was through their participation in consciousness-raising groups. These were discussion groups where women gathered together to discuss their personal lives.

In the course of talking about their personal experiences, women would find that they were not the only ones to be abused by their husbands or partners. They came to the collective conclusion that, contrary to what they had been told or previously believed, they did not deserve nor did they cause the abuse they suffered.

Many of the first domestic violence shelters emerged out of these consciousness-raising groups.

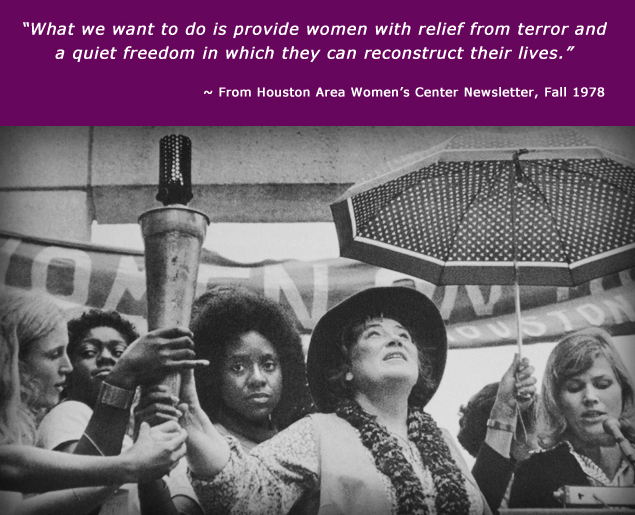

|

| The Houston Area Women's Center, established in 1977, was and still is dedicated to assisting victims of sexual and domestic violence. |

For example, in 1972 a group of women in Bangor, Maine established a battered women’s shelter called Spruce Run.

The women who founded this shelter discovered, in a consciousness-raising group, that they had all experienced intimate partner violence. Unable to see that abuse as part of a larger pattern of gendered power relationships, and with few resources to help them analyze their own lives or build new ones, they remained in abusive relationships far longer than they wanted.

Lou Chamberland, a founding member of Spruce Run, explained, “[T]he original idea was just a safe place…. I mean, that’s where we started from. Which goes, if you had a place, then people could go there and they’d be safe. At least they’d be safe.”

Literally without anywhere to escape from violence, battered women first looked to find spaces where they could feel and be safe. From there, they built programs, like job training, childcare, and transitional housing, to help abused women rebuild their lives and empower themselves.

“An Ice-Pack to Reduce the Swelling:” Battered Women and the Police

In the 1970s, battered women built shelters because they had few alternatives to abusive relationships. They also, however, wanted to change police policy with regard to domestic disturbance calls.

In 1976, six lawyers, after observing interactions between the police, court employees, and battered women, formed the Litigation Coalition for Battered Women (LCBW) and began to orchestrate a lawsuit against the New York City Police Department.

They found that police officers refused to acknowledge domestic violence incidents as emergencies, withheld information from battered women about making civilian arrests and filing protection orders, and evaded battered women’s efforts to take action against their husbands.

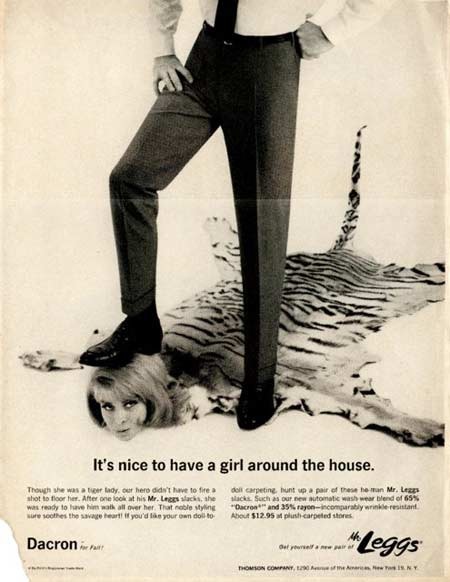

|

| Many advertisements made light of issues of domestic violence, including this 1970 ad for Mr. Leggs. |

Police officers clearly did not see domestic abuse as a serious or criminal offense. But they also felt as if they did not have the authority to place themselves between husbands and wives in the “privacy” of the marital relationship. Although NYPD training manuals claimed the police were “the only ones” to be able to “go into the home and deal with family violence,” officers were clearly uncomfortable with doing so in practice.

For example, on August 28, 1976, in Brooklyn, NY, when Kathleen D’Amico threatened to call the police after her husband choked her and repeatedly knocked her on the ground, he responded “’they’re not going to do anything. Go ahead and call them.’”

He was right.

As the plaintiff was walking to her local police department, her husband repeatedly knocked her to the ground for eight blocks. Two police officers showed up, but informed her that they could not arrest her husband because she did not have an order of protection. They also told her “’we have emergency calls and can’t spend all day here.’”

In other situations, women testified that police demonstrated tacit approval of domestic violence, joking with husbands and diminishing the legitimacy of the problem.

For example, the Brooklyn-based police officers who responded to Lydia Thomas in September of 1976 “mimicked Mrs. Thomas and … treated the entire situation as a joke.” New York City officers who responded to Jane Doe’s call for help in April of 1976 “joked around with Mr. Doe.”

Officers’ active dismissal and denigration of their calls for help made both Thomas and Doe feel helpless. Thomas claimed, “Now that my husband sees that the police are on his side and don’t care about me, he could kill me,” and Doe concluded that police behavior would “reinforce her husband’s violent behavior.”

Clearly frustrated, Doe gave up on the criminal justice system in August 1976, after enduring months of abuse by her husband and inaction by the NYPD. , “[She] thought about going back to court or calling the police, but she was so depressed by her earlier experiences that she thought it would be more effective to just get an ice-pack to reduce the swelling.”

The LCBW was able to force the New York City Police Department to abandon their informal non-arrest policy. By establishing a pattern of discrimination against married women, the group successfully argued that the NYPD was denying married women equal protection under the law, building on a legacy of civil rights legal cases that used the Fourteenth Amendment.

They also inspired legal challenges to police departments and non-arrest policies around the country. For example, a similar case was filed in Oakland, CA in 1976.

In the ten years after these two lawsuits were filed, the National Coalition against Domestic Violence recorded at least fifteen others that were filed by battered women against police departments across the country.

Mandatory Arrest Policies

|

| The Federal Violence Against Women Act of 1994 led to the creation of the Office on Violence Against Women to protect women in the home and other areas like college campuses. |

In response to this wave of lawsuits, police departments began implementing mandatory arrest policies for cases of domestic violence.

The first mandatory arrest law was passed in Oregon in 1977. And, when the Federal Violence Against Women Act was passed in 1994, it encouraged and rewarded states that adopted mandatory arrest laws.

These laws required law enforcement officers to step into the previously “private” world of the family and to approach domestic violence as public violence.

Activists in the 1970s supported mandatory arrest policies because they had seen how damaging police policies that avoided arresting batterers had been. They wanted to eliminate any ambiguity in the law because they thought it would be the best way to counteract what one court called a “policy of indifference” in the treatment of battered women.

Mandatory arrest policies became controversial in the 1990s, however. Some legal advocates considered these rules to have a “significant deterrent effect on batterers.” But those involved in the shelter movement saw such an approach as too reliant on law enforcement to provide solutions for domestic abuse.

Some feminists also argued that mandatory arrest policies went too far in restricting women’s autonomy, removing from them the choice of whether or not they want to pursue charges against their abusers.

Many feminists, such as legal scholar Kimberle Crenshaw, also believe that mandatory arrest policies have further discouraged women of color from calling the police. She argues that black women are often afraid they will contribute to the disproportionate incarceration of minority men, because black men in particular are “ stereotyped as pathologically violent.”

Domestic Violence Today

|

| Artist Joel Bergner's mural in Brooklyn, New York, entitled A Survivor's Journey, seeks to bring attention to issues of domestic violence. |

The importance of the boundary between private and public remains at the heart of questions of domestic violence today.

Janay Rice, shortly after the release of the elevator video in September 2014, lambasted the media for using what she understood to be a private matter between intimate partners in order to gain better their ratings.

“THIS IS OUR LIFE,” she claimed. “I want people to respect our privacy in this family matter.”

Despite Janay Rice’s refusal to press charges against her husband, he was charged because activists in the 1970s insisted that there be legal consequences for intimate partner abuse.

Ultimately, in May 2015, because he completed his pretrial intervention program, the charges against Rice were dismissed.

Domestic violence advocacy groups, like the National Coalition against Domestic Violence, have been concerned that the treatment of the incident and of Rice might send a message to the public that domestic violence should not be treated as a dangerous crime.

The organization released a statement after the charges against Rice were lifted, saying “The criminal justice system has essentially sanctioned and reinforced the reality that society and systems still do not understand the prevalence and crime of domestic violence. The message sent by these actions is that perpetrators of domestic violence will not be held accountable for their crimes.”

The case involving Ray and Janay Rice illustrates the difficulty in balancing the right to privacy in intimate relationships with the public interest in punishing perpetrators of domestic assaults.

Domestic abuse has historically been a crime that has gone unpunished precisely because of the private nature of intimate relationships. And it is for this very reason that it is important to keep public discussion of the issue alive in a way that encourages victims to come forward.

Daniels, Cynthia R., and Rachelle Brooks. Feminists Negotiate the State: The Politics of Domestic Violence. Lanham: University Press of America, 1997.

Feder, Lynette. Women and Domestic Violence: An Interdisciplinary Approach. New York: Haworth Press, 1999.

Fineman, Martha, and Roxanne Mykitiuk. The Public Nature of Private Violence: The Discovery of Domestic Abuse. New York: Routledge, 1994.

Freedman, Estelle B. Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation. 2013.Bottom of Form

Gordon, Linda. Heroes of Their Own Lives: The Politics and History of Family Violence : Boston, 1880-1960. New York, N.Y., U.S.A.: Viking, 1988.

McMillen, Sally G. Seneca Falls and the Origins of the Women's Rights Movement. New York: Oxford University Press, 2008.

Okrent, Daniel. Last Call: The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. 2010.

Pleck, Elizabeth H. Domestic Tyranny: The Making of Social Policy against Family Violence from Colonial Times to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

Rosen, Ruth. The World Split Open: How the Modern Women's Movement Changed America. New York: Viking, 2000.

Schneider, Elizabeth M. Battered Women & Feminist Lawmaking. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

Solnit, Rebecca, and Ana Teresa Fernandez. Men Explain Things to Me. 2014.

Suk, Jeannie. At Home in the Law: How the Domestic Violence Revolution Is Transforming Privacy. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2009.