Water created Israel, like water created the American West by enabling farming, encouraging an influx of settlers, and marginalizing – and expelling – Native Americans. Water remains a major tool of Israeli policy toward the Palestinians.

Since its founding in 1948, Israel has used hydraulic works to reinforce its ownership of occupied Palestinian lands. In November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted resolution 181 (II) partitioning Palestine into two states, one Jewish and one Arab, with Jerusalem under a UN administration.

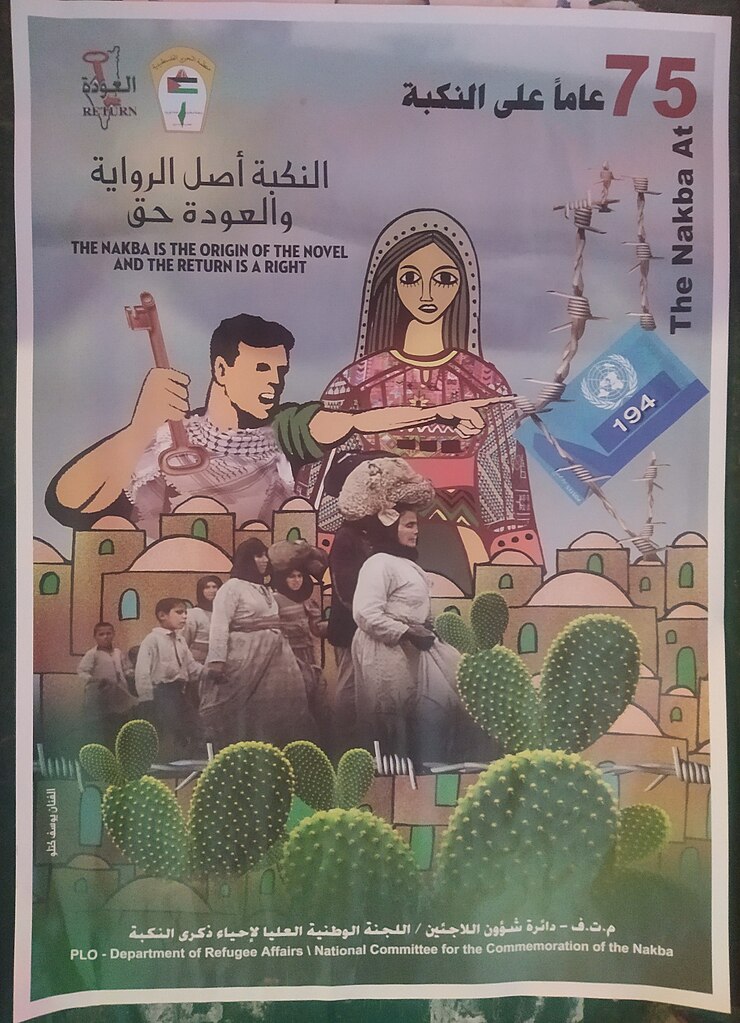

The Arab world rejected the plan. Jewish militias launched attacks against Palestinian villages, forcing thousands to flee. During the Arab-Israeli War, Jewish forces expelled Palestinians, confiscated Palestinian lands, and settled in Palestinian homes (the Nakba). Between 1948 and 1950, 500 villages and towns were destroyed by Zionist militias.

Israeli projects to rebuild the environment offer a fascinating and troubling history of the use of large-scale technological systems toward political ends. After the war, no less than it had with soldiers, guns, and other armaments, Israel pursued nature transformation projects to subjugate and transform Bedouin land and homes into the homes and land of Jewish settlers.

Drawing on studies of the United States’ Tennessee Valley Authority, and on the authority of the US Army Corps of Engineers, its engineers determinedly developed projects to secure water for fruit orchards, vegetable farms, and afforestation under the powerful and single-minded Mekorot, the National Water Company of Israel.

Mekorot claims it has conveyed “water, the source of life for more than 85 years.” Mekorot embodies “the unique Israeli spirit: daring, sophistication, and innovation” in the face of the challenge of providing water on the edge of the desert with limited sources of water that face “constant threats.”

The company employs dams and other barrages, pumps, irrigation systems, and agricultural systems fed with its water to encroach further on Palestinian land and push its people further into poverty, despair, and thirst. The displacement and dispossession of Palestinians continues, but with the paradoxical employment of green, or seemingly green, technologies as part of what analysts call an “environmental Nakba.”

Conquerors have long used technological “improvements” and extractive industries – mines, dams, irrigation systems, and plantations – to control resources and claim ownership of lands and people.

Dams in Brazil and India have led to the removal of millions of local residents, small farmers, and peasants as massive reservoirs inundate their farms, homes, and memories. Perhaps as many as 4 million Chinese peasants were forcefully relocated from the Yangtze River basin in the construction of the Three Gorges Dam, which was justified to the people on the grounds of environmental improvements, flood control, and power generation.

In the Middle East, Israel has turned environmental technologies, afforestation projects, and farms into tools of a 50-year war against Palestine. The environmental Nakba accelerated after the terrorist attacks of October 7, 2023.

Hydraulic Technologies as Instruments of Political Control

On October 7, 2023, thousands of Hamas and other Palestinian groups attacked Israeli settlements from the Gaza Strip, killing 1,139 people and kidnapping others. The murderous attack was a response to Israel’s blockade of Gaza and occupation of Palestinian lands. Israel responded to the attacks with understandable fury.

But after the initial response, in addition to indiscriminate military attacks on civilians, hospitals, and schools, it has used its hydraulic systems as tools of war. Pursuing collective punishment, it limited the access of more than 2 million Palestinians in the Gaza Strip to water, and has killed more than 46,600 people, many of them women and children.

Its armies have targeted Palestinian waterworks, among them a key reservoir, and the electrical infrastructure including solar panels that power four of Gaza’s six wastewater treatment plants. These documented human rights violations are in fact a continuation of a policy that President Jimmy Carter referred to as Apartheid – the legal and physical separation of Palestinians from property, resources, and recourse to law by Israelis – dating to the 1950s.

By the end of the 19th century, Palestine had grown to some 1,300 small villages and towns primarily dedicated to agriculture. The environmental Nakba that accompanied the 1948 conquest destroyed both lives and the natural environment of these sustained communities.

Engaging in a kind of “ecological imperialism” involving the introduction of new specials of plants and animals intentionally or coincidentally during colonial conquest, European Jews in Palestine replaced such native trees as oaks, carobs, and hawthorns and crops such as olives, figs, and almonds with European pine trees that “reduced biodiversity and harmed the local environment.”

Israel used hydraulic technologies to secure settlement in occupied lands and establish agricultural oases of newly introduced trees and crops. During the first years of its existence, Israeli leaders developed a national water system, independent and isolated from neighboring countries, even if the water resources – the Sea of Galilee for example – were common resources of the Mideast.

The Jordan River basin is shared by Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Israel, and Palestine. An endorheic river, it flows north to south through the Sea of Galilee and drains into the Dead Sea. Israeli engineers were determined to make the sea meet Israel's water requirements.

During the Cold War, a number of hydraulic projects moved forward with the assistance of engineers and financing from the superpowers: Egypt’s Aswan High Dam with Soviet assistance, Brazil’s Companhia Hidro-Elétrica do São Francisco that built dams in consultation with the U.S. Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), others in Amazonia that bought turbogenerators from the USSR’s Elektrosila, and Israel’s major waterworks.

Israel also consulted with the TVA. In Palestine, Land of Promise (1944), Walter Clay Lowdermilk, an American soil scientist, proposed a Jordan Valley Authority based on the TVA model.

Emanuel Neuman, an American Zionist leader, “inspired by Lowdermilk's idea,” asked TVA engineer James Hayes to produce a detailed blueprint for a Jordan River system. Hayes's 1949 report, TVA on the Jordan, proposed diverting Lebanon’s Litani River “along with the Jordan tributaries and available groundwater sources projected a total water supply of 2.5 billion m3” to supply up to 4 million people.

In August 1949, the United Nations Palestine Conciliation Commission established an economic commission under TVA Chairman Gordon Clapp to investigate the problems involved in finding homes for Arab refugees. The commission report called for the creation of public works programs to provide employment.

The United Nations, the United States, and other actors intended water as a boost to nascent Israel’s stability and as a solution to the horrors of displacement and growing numbers of Nakba refugees, not as a tool of Israeli colonization.

By 1953 the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) for Palestine Refugees in the Near East was working on an agreement with the Kingdom of Jordan to fund a scheme to use the waters of the Jordan and Yarmuk Rivers for irrigating the Jordan Valley and for establishing refugees there.

UNRWA commissioned the TVA to undertake the survey on the basis of “sound engineering practice” without concern for political boundaries in search of the most efficient method of utilizing the waters in the interests of all parties. The resulting $121 million project would provide irrigation and electric power for Jordan, Syria, and Israel. Together the projects were intended to stimulate economic growth and cooperation, create conditions for resettling refugees in Jordan, and result in peace treaties with Israel and her neighbors.

The United States endorsed the plan with Israel to bear a portion of the burden for settlement and repatriation of the Arab refugees, including within Israel, in this case by sharing available water and by agreeing to minor territorial adjustments. But the Arab League rejected this approach and demanded only refugee repatriation to Israel.

For its part, Israel rejected the TVA plan. Pinchas Lavon, Israel's Minister without portfolio, charged the United States with employing the concept of “development of underdeveloped areas” to deny “Israel’s right to use the little natural resources in her possession.”

Israel Water History

Israel determined to develop a national, independent water system isolated from neighboring countries to support the growing nation and agricultural settlement. In its early years, the main source of drinking water in addition to the Sea of Galilee was water from its coastal and mountain aquifers.

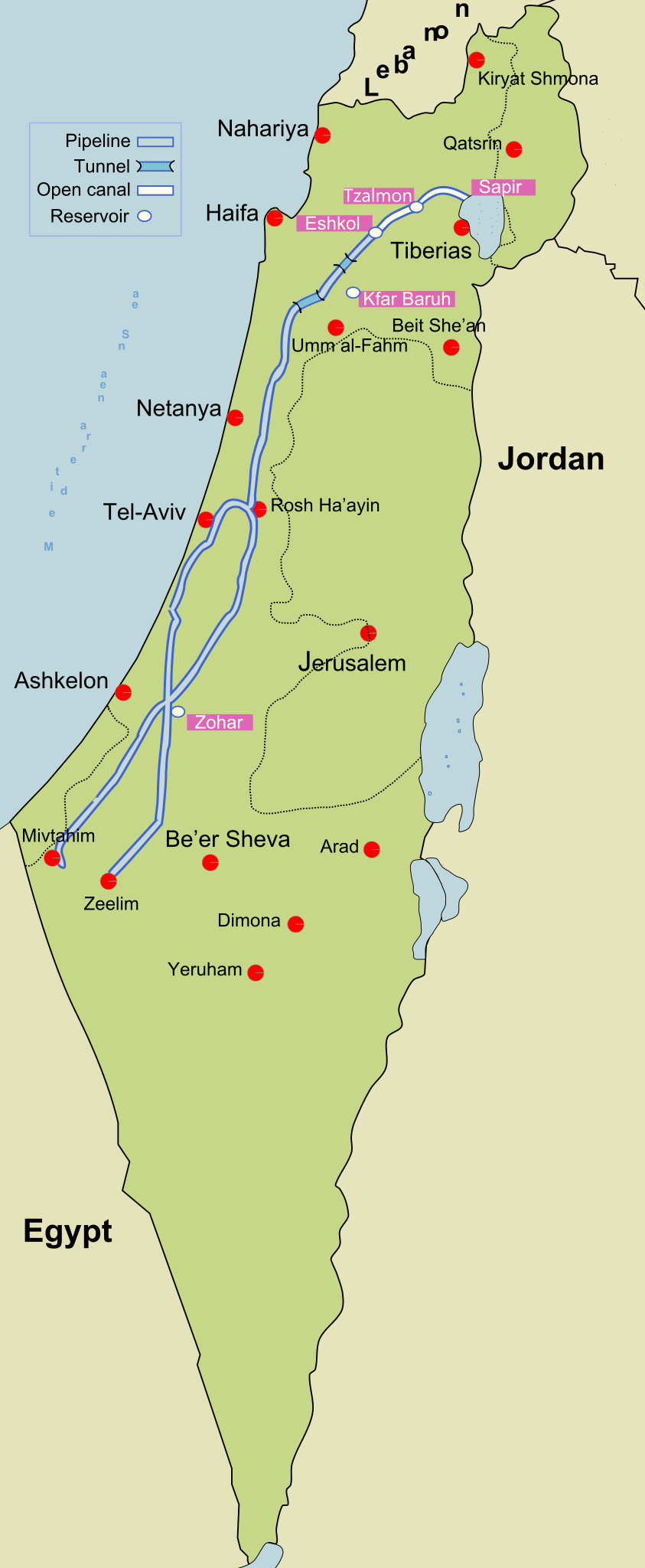

To supply water from these resources to southern parts of the country, Israel decided to construct a National Water Carrier (NWC) with canals, tunnels, and pipelines. The Israelis determined that the Hayes plan, with a system of 29 reservoirs to hold water for summer months and droughts, would not work given the porous local soils. The NWC, which enabled Israel’s control of the region’s water, was the backbone of all subsequent hydraulic projects.

The National Water Carrier of Israel was a “physical manifestations of the Zionist vision,” in its early years transmitting 80% of its water for agriculture and 20% for home use. The NWC extends 130 kilometers from the north of the country to the arid south and enables the establishment of settlements in the desert. The waters of the north would “make the south bloom” and enabled the Zionists to claim that Israel could continue to absorb many Jewish immigrants.

After touring several TVA dams and facilities that contributed to flood control, hydroelectricity, reforestation, fertilizer production, and transport in May 1951, Israeli President Ben Gurion, who was familiar with Lowdermilk’s book and Hayes’s project, made the decision to pursue the NWC. Excavation began in 1953, and through the efforts of 4,000 workers, it was completed in 1964.

With population growth, an increase in water consumption, and depletion of groundwater, Mekorot, the insatiable, bulldozing Israeli Water Company, found new ways to manufacture and control water. Mekorot expanded irrigation in the Naqab (Negev) Desert through reclaimed effluents from the Shafdan Water Treatment Plant (WTP) and the construction of the Third Water Line which carries 140 million m3 of recycled water annually from Israel’s cities to the desert.

Mekorot next spliced new water lines into the NWC to accommodate desalinized water, which is Israel’s primary source today of household use (drinking) water. Droughts and population increase in the 1990s led to the further development of desalination of water for drinking purposes and the construction of more WTPs for agriculture reuse.

Large-scale desalination has been the rule since 2005 from which Israel gets about 75% of its water. Drip irrigation, first introduced in the early 1970s, helped lower water consumption for agriculture somewhat. In the 2020s to protect the Galilee from further damage, Mekorot “reversed” the flow of the NWC with desalinated water to feed the Galilee.

“Making the Desert Bloom”: Trees as a Tool of Israeli Apartheid

With land and water under its control, Israel has proudly embraced afforestation projects to push back the desert. Yet tree planting has been used to displace Palestinians from their lands, including in parts of the occupied West Bank. The massive Yatir Forest project in the Naqab desert was funded in part by U.S. charitable donations through the Jewish National Fund (JNF, 1901-present, created to secure land for the Zionist movement).

The JNF claims that the 250 million trees planted in Israel since are “a beneficent act of environmentalism and a means of memorializing loved ones.” But revealing the clearly colonizing intention of the trees, forestry workers who plant them are accompanied by military police to remove the Bedouin presence.

In fact, after the Nakba in 1948, the Israeli government has used tree planting to remove Palestinian communities, “conceal the ruins” of these communities, and “hide evidence of yet others already destroyed.”

As for the touted environmentalism of the Yatir Forest (at 30 km2 or 7,413 acres): supporters say it holds back the desert, retains moisture in the soils, and captures carbon dioxide. If it enables Jewish settlement and turns the desert into Eden, then it has a universal benefit for Israeli society. In reality, afforestation has “obliterated a diverse ecosystem for rare species.” It may in fact be accelerating climate change by retaining more heat than the desert previously reflected back into space.

Israeli viticulturists have been forced to draw on ancient history to justify vineyards that produce 150,000 bottles annually. The winemakers call the Yatir vineyard a “testament” to a wine industry with roots dating back 2,500 years to the first reign of the kings of Judah. But desert vineyards use copious amounts of water irrigation, fermentation, cleaning equipment, and so on.

During its occupation of the West Bank, the Israeli government has established 48 natural reserves. In 2020, for the first time since the Oslo Accords, Israel announced the creation of seven new nature reserves, adding another 5,300 hectares to the total area of nature preserves in the occupied lands of 69,939 hectares. The designation of reserves under the jurisdiction of Israel’s Nature and Parks Authority enables severe restrictions on Palestinian landowners wishing to use the land for farming and grazing.

The Israelis build forests in one place and destroy trees in others. Farmlands have become battle zones where Jewish settlers eject Palestinian inhabitants whose trees and crops they burned. Olive trees make up nearly half of the agricultural land in the West Bank and Gaza. They are crucial to Palestine’s national income and exports. But since the 1967 war, Israel has destroyed over a million olive and fruit trees in occupied Palestine.

In April 2015, Israeli settlers from the Immanuel settlement uprooted some 450 olive trees and saplings from lands in Deir Istiya on top of 120 olive trees uprooted in Wadi Qana. This has threatened the livelihood of 80,000 families. The violence against farmers and their crops continues into the 2020s in Awarta, al-Tuwani, Salfit, and other Palestinian towns.

All of these projects – hydraulic works, irrigation systems, afforestation projects, and nature reserves – are, as Sasa writes, “green colonialism” – that is, “the misappropriation of environmentalism to eliminate the Indigenous people of Palestine and usurp its resources.” Nature reserves and forests thus help to “justify land grab, prevent the return of Palestinian refugees” and to “dehistoricize, Judaize, and Europeanize Palestine.”

The Gated Country

Approximately equal numbers of Jewish Israelis and Palestinians live today between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan River, an area encompassing Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), the latter made up of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. Throughout most of this area, Israel is the sole governing power; in the remainder, it exercises primary authority alongside limited Palestinian self-rule. Israeli authorities methodically privilege Jewish Israelis and discriminate against Palestinians through laws, policies, army intervention, and technological systems.

Israel uses other technological systems to enforce separation. In fact, Israel has become a gated technological community in which the authorities refuse to connect Palestine and Palestinians “to the national electricity or water grids or to provide even basic infrastructure such as paved roads or sewage systems.”

Water insecurity is a global problem. Two billion of the Earth’s residents lack proper sanitary facilities. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers 100 liters per capita per day (lcd) as the minimum for domestic consumption of water. But Israel controls hydraulic infrastructure, and it has purposely diverted water from Palestine.

The Palestinian Water Authority (PWA) has set a target of 120–150 lcd for its population. Owing to Israel’s control of water, the domestic consumption in the West Bank is only 62 lcd, and in Gaza, it is 89 lcd. With the West Bank and Gaza populations growing, demand for water will increase. In fact, Israel has ignored negotiated agreements of the Oslo II Accords with Palestine for groundwater abstraction and imports of additional supply, and it controls West Bank aquifers to the benefit of Israeli settlers.

To seal off and control confiscated territories, the Israelis have built roadways covering more than 100 km2, primarily to serve settlers. “Trees and any buildings within seventy-five meters of these roads are bulldozed and declared closed military zones to the Palestinians,” scholars Mazin B. Qumsiyeh and Mohammed A. Abusarhan have asserted.

In a struggle to limit terrorist attacks, the Israelis built a barrier wall over 700 km long that isolates 9% of the land and approximately 25,000 Palestinians from the rest of Palestine. Like roads, the 9-meter-tall wall, together with associated other fence systems, barbed wire, intrusion detection equipment, anti-vehicle ditches, and patrol roads, obstructs human and animal activity and destroys biodiversity.

Finally, Israel has transferred the burden of industrial pollution to the West Bank and Gaza. The major culprits are the Geshuri pesticide and fertilizer complex and the Barkan industrial park, the largest in the West Bank and the second largest in Israel, with its factories for plastics and metal works and other facilities that handle electronic wastes. Untreated wastewater courses through neighborhoods containing viruses, bacteria, parasites, toxic metals, and other pollution. The industrial pollution destroys public health, vegetation, and agricultural lands.

“Letting the Desert Bloom” Reprised

The environmental Nakba has been greenwashed thoroughly by the myth of the heroic kibbutz settler. The kibbutz, a collective agricultural outpost, grew out of the Zionist movement in the early 1900s. By the 1960s, after the state expelled the Bedouin population from the Naqab Desert, it sponsored kibbutzim for vegetable production.

Like the Russian peasants sent by the Tsar and the Soviets to settle – and control – the land of nomadic Central Asians, or the heroic yeoman farmer in the United States who evicted Native Americans from their homelands in the name of hard work and agricultural improvement in a hostile environment, so the kibbutz settler was a hero: an independent, hardworking, and honest man and who toiled in communion with beneficent nature.

Eventually, Israeli settlers, both in these collectives and not, would “make the desert bloom.”

Yet this myth of bloom and hard work obscures the violence that the Jewish settlers did to Palestinians and their land. First, the introduction of European farming methods and non-native animals by European Jews had an ecological impact. They contributed to the decline in many native species, destroying biodiversity.

Second, the Kibbutzim are sites of racial injustice and militarism. The collectives exclude large swaths of the population from joining them. They employ Palestinians to do menial labor, pick cotton, and collect garbage, but not as full members. Further, kibbutzniki are critical actors in the Israeli military machine. Kibbutzes comprise 4% of Israel’s population, produce 10% of GDP, and supply over 25% of the air force pilots and army officer corps.

Israeli engineers claim that their water projects magically avoid many of the environmental costs usually associated with agriculture through drip technologies, GPS, and reclaimed waste effluents. Foresters tout the planting of trees and vineyards.

Yet Israelis have a significant and growing per capita ecological footprint. Their projects use pesticides widely. Their forests and waterworks directly lower biodiversity. Their NWC takes water from Palestinians.

Israel’s importunate use of water resources has emptied Palestinian wells and decreased the amount of water that can be produced from other wells and springs. By 2008, Palestinians pumped only 31 million m3 of water – 44% less than they produced prior to the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement of 1995. Less water meant neglect for farmland and a switch to growing less profitable crops.

Israeli settlements have destroyed hundreds of thousands of olive, citrus, date, and banana trees. Their green settlements are, in fact, isolated Zionist Edens that hide the expulsion of Palestinians from their homes and lands.

In these and other shocking ways, Israel engages and operates technologies of agricultural improvement and water supply selectively – to support Jewish settlement, but to place the entire costs on the Palestinian population.![]()

Learn More:

Jimmy Carter, Palestine Peace Not Apartheid (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007)

Alfred W. Crosby, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900, 2nd Edition (New York: Cambridge, 2015).

Human Rights Watch, A Threshold Crossed: Israeli Authorities and the Crimes of Apartheid and Persecution (April 2021)

Walter Clay Lowdermilk, Palestine: Land of Promise (London: London Victor Gollancz Ltd, 1944).

Mazin B. Qumsiyeh and Mohammed A. Abusarhan, “An Environmental Nakba: The Palestinian Environment Under Israeli Colonization,” Science Under Occupation, Vol. 23, no. 1 (Spring 2020), at https://magazine.scienceforthepeople.org/vol23-1/an-environmental-nakba-the-palestinian-environment-under-israeli-colonization/

Ghada Sasa, “Oppressive pines: Uprooting Israeli Green Colonialism and implanting Palestinian A’wna,” Politics Vol. 43, no. 2 (2023), 219–235.

Alon Tal, Pollution in a Promised Land. An Environmental History of Israel (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002).

World Bank, Securing Water for Development in West Bank and Gaza (Washington: World Bank, 2018)