“The wishes of the people are not fulfilled… The people of which we speak is no longer the mere idea of former times: no, it means Everybody, Everybody! Yes, your Royal Highness, Everybody!” — Hanau People’s Commission to Prince-Elector Friedrich Wilhelm, 1848.

On March 9, 1848, the twenty-three members of the Hanau People’s Commission—leading citizens of the small German city on the Main River, upstream from Frankfurt—declared their participation in the quickly-spreading upheaval of the March Revolutions of 1848.

Their target was Friedrich Wilhelm, the Prince-Elector (in German, Kurfurst) of Hesse, the sovereign ruler of a principality stretching from Hanau north toward Fulda, Marburg, and Kassel, the city of the Prince-Elector’s residence.

This made Hesse a small, but notable, part of the German Confederation, an association of thirty-nine independent states extending north from the Alps to the Baltic Sea, and from Luxemburg in the west to the modern Polish city of Katowice, in the east.

The Prince-Electors of Hesse were not major powers of the Confederation, like the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire. And yet, in March 1848, the inhabitants of Hanau, as with other cities in Hesse and states across the German Confederation, were inspired to make new demands of their rulers.

These demands would—and in the end unsuccessfully—include the establishment of a unified, constitutional German nation-state to replace the unwieldy Confederation and its patchwork arrangement of territories ruled by various kings, princes, and dukes, and a handful of independent city-states.

In German cities from Mannheim to Berlin, and Dresden to Vienna, crowds gathered, constructed barricades and demanded rights and liberal reforms, including the freedoms of religious belief and practice, speech and assembly, the end of press censorship, amnesties for political convictions, and representative government, perhaps even an elected all-German parliament.

In some places, notably Berlin and Vienna, the uprisings turned violent, with armed confrontations between the crowds and military units. And most notably, across the German Confederation, these crowds adopted a tricolor banner with horizontal bands of red, black, and gold, colors associated with German resistance to Napoleonic domination decades earlier.

The inspiration for these uprisings came from Paris, where in late February 1848 protests erupted against King Louis Philippe, who came to power after the 1830 revolution in France. Louis Philippe abdicated on February 24, and a new French Republic was proclaimed the following day. The Parisian revolution may have been inspired in turn by uprisings in Sicily in January 1848, which forced their king to accept a constitutional monarchy.

In March 1848, various councils set up by leading citizens of cities throughout the German Confederation—like that in Hanau—demanded the formation of an all-Confederation parliament to replace the ineffective Federal Convention, an advisory council comprising appointees of the Confederation monarchs.

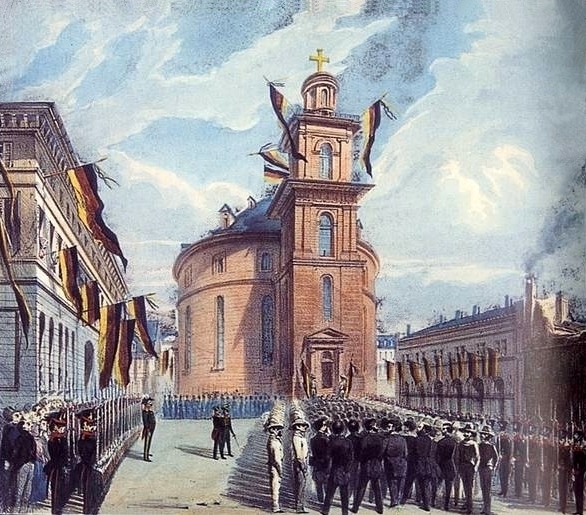

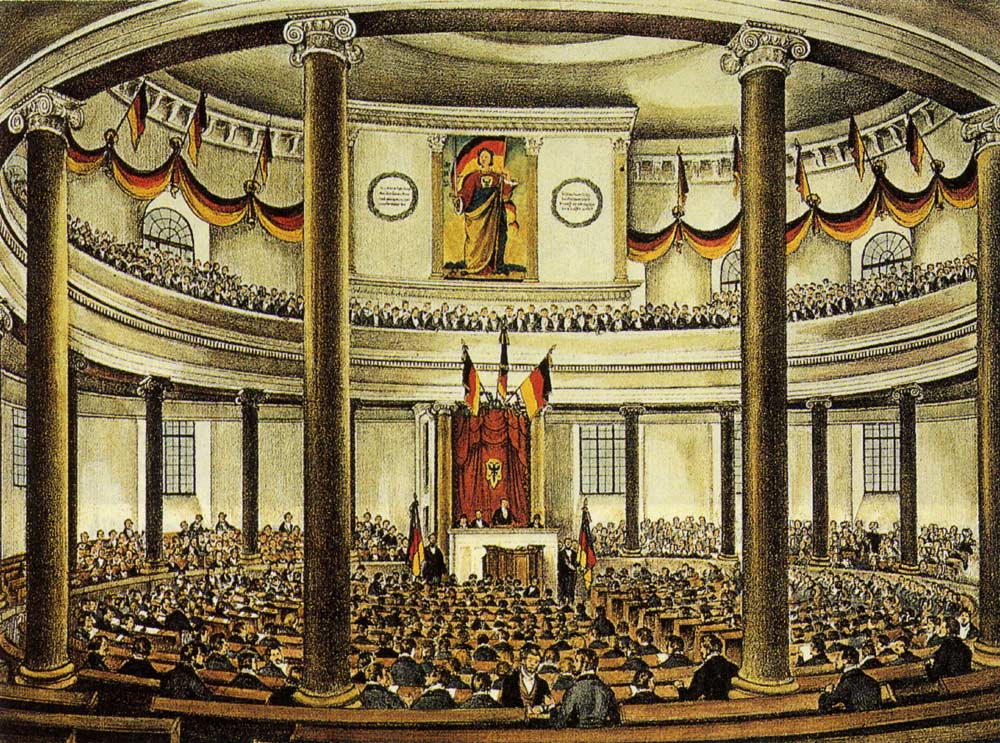

In attempts to forestall further revolutionary violence, many rulers across the Confederation appointed ministers responsive to these demands. A preliminary meeting of representatives began in Frankfurt on March 31, and the new National Assembly met for the first time in St. Paul’s Church in central Frankfurt on May 18.

Given the emotions of the March protests, hopes were high that the assembly would produce an all-German constitution that would set the Confederation on a path toward a more unified national future, perhaps with the King of Prussia as the head of state. In the end, though, the National Assembly did not achieve those long-term goals and disbanded in March 1849.

While the Assembly produced a constitution and declaration of rights, this outcome was unacceptable to many of the rulers of the various states in the Confederation. A few committed revolutionaries continued to fight for a liberal-democratic German nation-state, but by late 1849, these uprisings had, like the National Assembly in Frankfurt, faded with few enduring effects.

Today, however, the legacies of the National Assembly—and the uprisings of 1848 more broadly—remain important to the self-image of modern Germany.

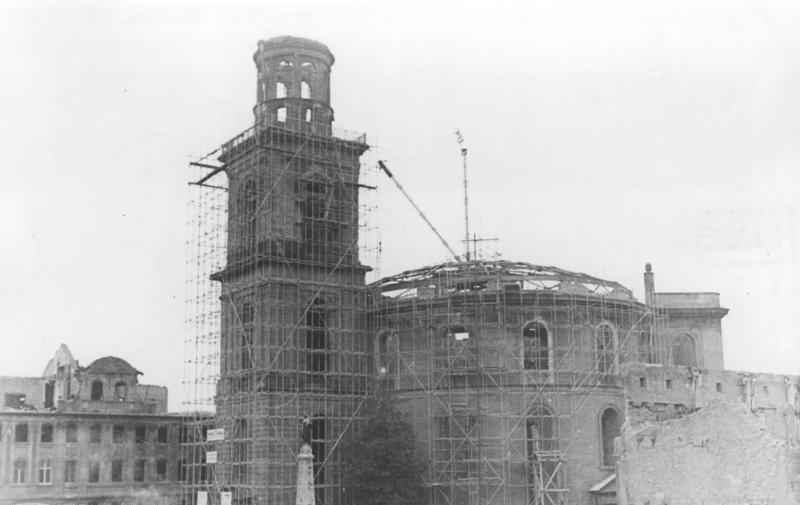

The revolutionaries’ black-red-gold tricolor became the flag of both East and West Germany in 1949 and remains the flag of Germany today. And St. Paul’s Church in Frankfurt, destroyed by Allied bombing during the Second World War, was the first public building in the city to be rebuilt after 1945; the project attracted donations from across the war-torn and occupied country and finished in time for the centennial of the National Assembly in 1948