“Undoubtedly there is something in the Slavic nature which predisposes those of Slavic blood to open a window, and in a liberal spirit and with a large gesture invite an enemy to become an angel without further preparation or a flying machine.”

The New York Times author who made this assertion in response to a Serbian political assassination in 1903 supposed the “reason must be sought in the ancestral habits of Russians, Poles, Servians, Sorbs, Polabians, Croats, Cassules, Wends, Lusatians and other stripes and variations of the type. They were forest-dwelling tribes living in square-built log houses generally provided with a door, a fireplace of some kind, and a chimney or smokehole…. The only exit was the smokehole, or in the finer habitations, a window. Ages of indulgence in vodka, brandy and other fire waters with the concomitant excitement of thrusting an opponent through the window or up the smokehole have made the Slav a slave to the window.”

Woodcut print depicting the Second Defenestration of Prague in 1618.

The act of defenestration is, in fact, designed to settle an argument by tossing an opponent out a window and the New York Times author might be forgiven his prejudice given the fact that there are three acknowledged Defenestrations of Prague (1419, 1618, and 1948). May 23, 2018 will mark 400 years since such an act of conflict mediation sparked the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) and plunged Europe into yet another period of religious violence and political upheaval.

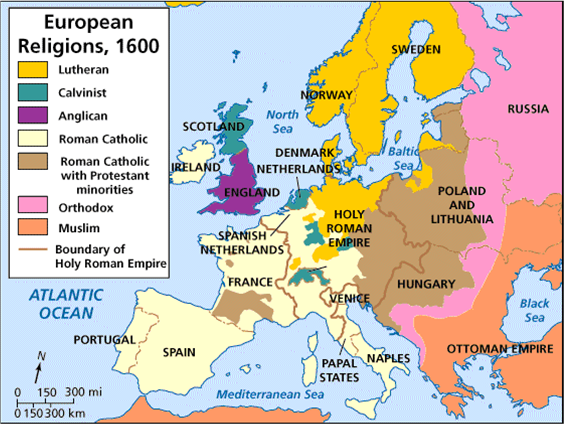

Religion and politics were inextricably intertwined in 16th- and 17th-century Europe with the religion of the ruling class often determining the religion of the state. Before Martin Luther nailed his 95 Theses to the church doors of Wittenberg in 1517, the thrones of Europe were Catholic. The Reformation, however, turned religion into a political tool. Monarchs, princes, states, and empires aligned as either Protestant or Catholic and preferred their populations adhere to the ruling religion.

The 1555 Peace of Augsburg had attempted to resolve these disputes by creating an accord between Catholic and Protestant (namely Lutheran) Europe. However, the Peace of Augsburg excluded reference to Calvinism and by the early 17th century, a growing number of Germanic principalities identifying with this denomination of Protestantism felt excluded from its protections.

Map showing religious groups in Europe around 1600.

The Thirty Years War occurred primarily in the Germanic lands of the Holy Roman Empire and pitted Catholic rulers against their Protestant counterparts. And while primarily a religious conflict, it also possessed a secular and dynastic dimension.

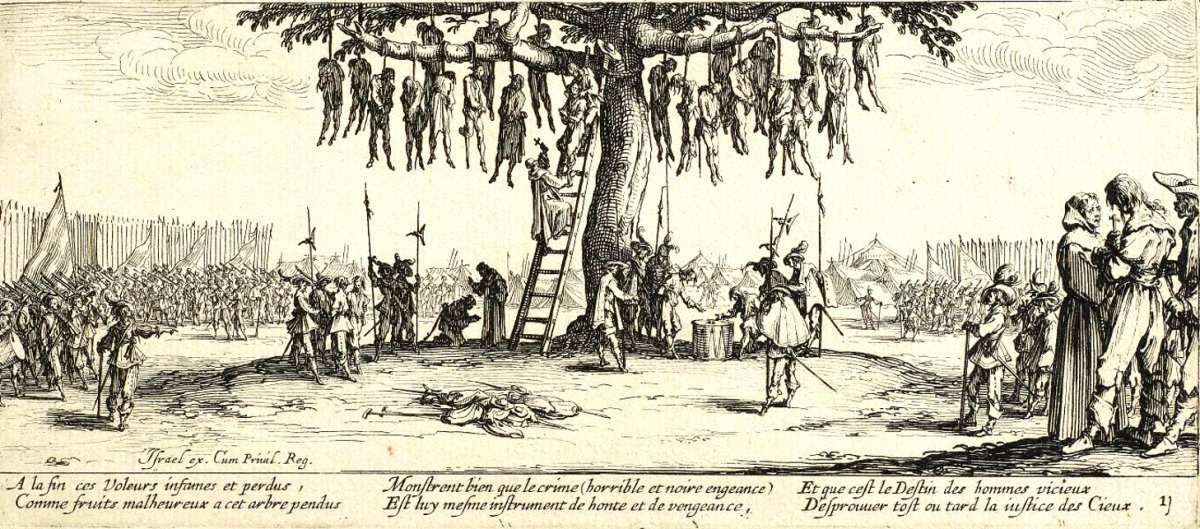

Arguably the most destructive period of warfare the European continent had yet witnessed, the Thirty Years War stands as a testimony to what can happen when political acrimony, religious intolerance, and unfettered attempts to silence the political opposition are left unchecked.

In many respects, the conflict began as an attempt by the royal House of Habsburg to reassert political power in Central Europe in areas with concentrations of Protestants, like the capital city of Bohemia, Prague.

Bohemians grew increasingly unhappy with the mounting assertion of political control over their lands and what they interpreted as the attempt to re-Catholicize the territory by Ferdinand II, Habsburg King and Emperor.

Consequently, the predominantly Protestant aristocracy of Bohemia, known as the Estates, began to plot a way of unseating Ferdinand as Holy Roman Emperor and replace him with the Protestant (Calvinist) Frederick V of Palatinate.

The tensions between the Estates and the Habsburg court in Vienna came to a head in the spring of 1618 when Ferdinand ordered the destruction of Protestant churches on Catholic Crown lands in Bohemia. The Bohemian Estates understandably interpreted this an attack on their religion, a restriction of their noble privileges, and a betrayal of legal guarantees they had received under Ferdinand’s predecessor.

Consequently, on May 23, 1618, a delegation of Bohemian aristocrats stormed Prague Castle where Ferdinand’s representatives resided, held a mock trial, found them guilty, and promptly tossed them from a third story window just off the main hall of the castle.

The Prague Castle, where Vilém Slavata and Václav Bořita were defenestrated from the top floor window in 1618 (left), and the interior of the defenestration room inside the castle (right).

The Second Defenestration of Prague was now in the history books.

Vilém Slavata of Chlum and Václav Bořita of Martinice, the two unfortunate royal advisors who were invited to become angels that afternoon “without further preparation or a flying machine,” survived the approximately 70 foot fall from the window.

Fortunately for the airborne advisors, adjacent to the wing that housed the offices from which they were defenestrated (yes, it is a verb) was a large hall often used for indoor equestrian events. A natural by-product of these events was the accumulation of a rather large pile of horse manure in the courtyard below these windows.

The Defenestration of Prague of 1618 by Karel Svoboda.

It was this pile of spongy fertilizer and not—as Habsburg propagandists immediately asserted—angels swooping to the rescue of the righteous and aggrieved Catholic ministers, that prevented mortal injury to Vilém and Václav. It enabled them to affect an immediate retreat to Vienna where they reported the whole ordeal to an enraged and indignant Ferdinand.

What followed was the full onslaught of the Thirty Years War that pitted Catholic and Protestant monarchs against each other and tore the social, economic, and political fabric of Europe.

The Bohemian Estates deposed Ferdinand as their king and elected Frederick V in his stead. His brief tenure on the throne gave him the moniker the Winter King. Refusing to accept the actions of the Bohemian Estates, Ferdinand enlisted the support of other Catholic monarchs in Europe including his Spanish Habsburg cousins and marched on Bohemia.

On November 8, 1620, his forces prevailed at the Battle of White Mountain on the outskirts of Prague. Frederick V relinquished the crown and fled into exile in the Netherlands. Ferdinand, meanwhile, reclaimed his crown, confiscated all Protestant noble lands, declared all of Bohemia a hereditary Habsburg possession, and re-established Catholicism as the sole official religion of his territory.

A Scene of the Thirty Years War, by Ernest Crofts, 1884.

Resolved in Bohemia, the religious war raged on for an additional 28 years wreaking havoc across much of central and northern Europe until the Peace of Westphalia brought an end to open hostilities, safeguarded the practice of religious choice, and brought to an effective end the Holy Roman Empire.

The occasion of this 400-year anniversary of the Second Defenestration of Prague provides an opportune moment to pause and consider the consequences of a culture of divisive politics, intolerance for opposing religious viewpoints, and a climate of public discourse that would rather silence opposing views by chucking them out a window (literally and figuratively speaking).

This unique historical moment is perhaps more familiar to us than we might first imagine and offers a lesson about the dangers of defenestrating viewpoints we find uncomfortable.