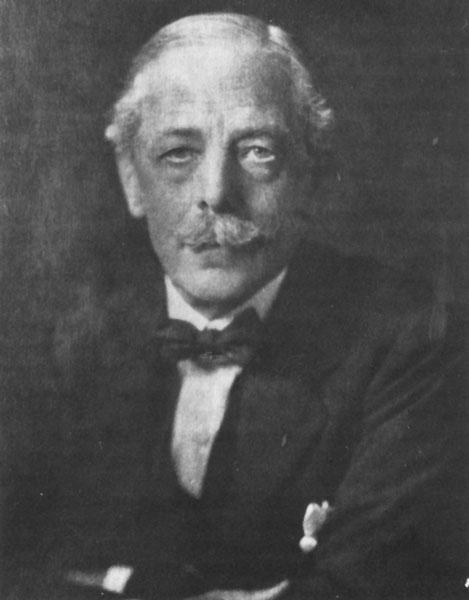

In The British Way of War: Julian Corbett and the Battle for a National Strategy, Andrew Lambert, Professor of Naval History at King’s College, London, examines the debates surrounding the development of British national strategy at the turn of the 20th century through the lens of the prominent intellectual, Julian Corbett. Corbett possessed immense personal wealth that enabled him to socialize with Britain’s ruling class while maintaining his intellectual independence.

Corbett’s work applied lessons derived from extensive historical research to the problems of modern maritime strategy and it formed the focal point around which the debate regarding British national strategy revolved from 1902 to 1922.

Lambert expertly deconstructs Corbett’s arguments by organizing the book chronologically, using Corbett’s major publications to provide a framework for the discussion of British strategy. Lambert puts these publications in conversation with the views and policies of leading figures in the British government and military during that time.

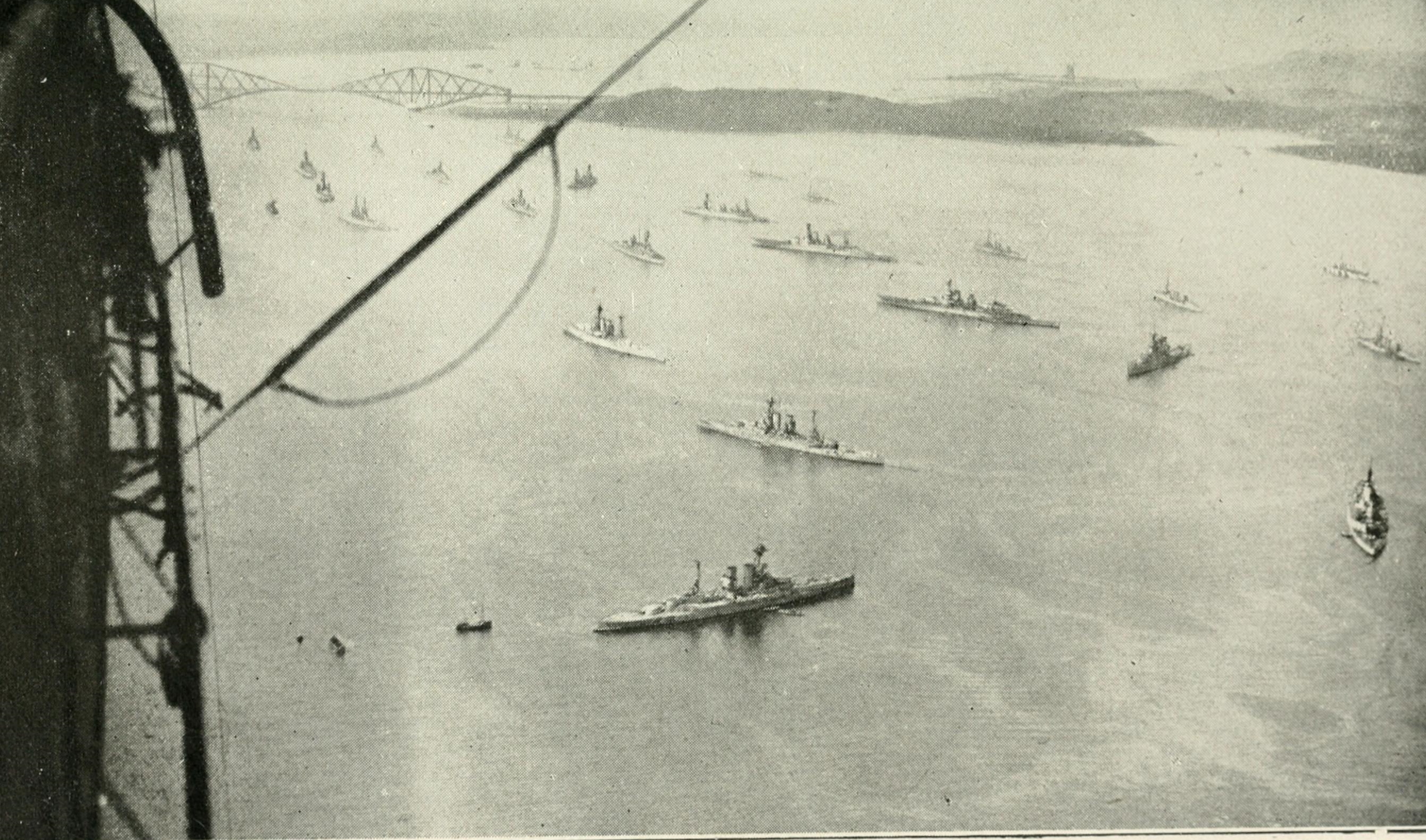

Corbett rose to prominence during an uncertain period in British strategic development. Technological innovations, particularly torpedoes, submarines, mines, and dreadnaughts, caused Britain’s maritime strategists to question the feasibility of the close blockade as the primary means of employing naval superiority. Simultaneously, German success on the continent of Europe in the late 19th century led to the emergence of a new school of thought, spearheaded by the General Staff, that emphasized mass, conscript armies fighting short, decisive campaigns on land as the future of British strategy.

Corbett sought to dispel this strategic uncertainty by elucidating a British way of making war from a vigorous study of past conflicts. He argued the British way of making war consisted of employing the army and navy in mutually supporting roles to achieve maritime objectives that furthered national strategic priorities.

Corbett disavowed continental commitment and mass armies, believing Britain should instead rely on its allies to bear the burden of land warfare while Britain destroyed the enemy’s ability to make war by attacking seaborne commerce and overseas possessions.

Finally, he contended that Britain’s strategy should seek to deter war and maintain a balance of power in Europe, thereby preventing the emergence of a European hegemon capable of threatening Britain’s security.

Corbett rejected the notion of fixed strategic principles that applied to all states equally. Instead, he argued each state must develop a strategic doctrine, informed by that state’s strategic culture, geographic considerations, and history. Strategic doctrine would then enable leaders to set appropriate priorities. Statesmen, not military officers, should set national priorities and coordinate the various instruments of government to achieve goals that further those priorities.

Corbett’s ideas regarding strategy significantly influenced British policymakers, particularly those in the Royal Navy, leading up to World War I. He faced significant opposition from army leaders who felt the German way of decisive land battles was the way of the future. In the summer of 1914, army leadership held the preponderance of influence in the government and committed Britain to fight alongside France on the continent.

Lambert attributes Britain’s strategic failures in World War I to the cabinet’s refusal to conform to Corbett’s British way of war. During World War I, Britain failed to coordinate maritime and continental strategy and committed a mass conscript army to the continent, the opposite of Corbett’s vision. The result for Britain was the loss of life on an unprecedented scale and economic devastation. Corbett did not remain silent during the war. He continued to publish essays and lectures and corresponded with his allies in government.

Corbett argued that Britain should withdraw the British Expeditionary Force from the continent and transition to a maritime strategy. The Royal Navy should fight to control the Baltic Sea, supported by limited land campaigns in Belgium. According to Corbett, this maritime campaign would cripple Germany’s ability to make war.

Although he failed in his attempts to change Britain’s wartime strategy, Corbett exerted great influence over the peace that followed, particularly in denying the American request for freedom of seas and codifying belligerent maritime rights to blockade and seize contraband under the aegis of the League of Nations. Corbett continued to lobby for his strategic vision until his death in 1922.

The greatest limitation of this book lies in Lambert’s reluctance to explore the weaknesses in Corbett’s arguments. In particular, he does not discuss Corbett’s failure to account for Britain’s continental commitment during the Seven Years’ War. In his study of strategy in World War I, Lambert supports Corbett’s desire to withdraw the British Expeditionary Force and return to a maritime strategy without examining the impact that the withdrawal would have on the balance of forces on the Western Front.

Lambert concludes by attributing Britain’s survival in World War II to its conformity to Corbett’s strategic principles but does not examine the failure of Britain’s maritime strategy. Britain’s strategy, focused on controlling sea lines of communication and attacking the Nazi periphery, did not significantly harm Nazi Germany until it was complemented by strong land forces in Europe.

Despite this limitation, Lambert’s book is an outstanding examination of British strategy in the early 20th century and Corbett’s role in developing that strategy. It is relevant to anyone interested in British military history and students of strategy. While fault can be found with Corbett’s arguments, his overall principles are sound and provide guidance for those developing strategy today. Civilian statesmen must set strategic priorities and coordinate the various instruments of government to achieve goals that align with those priorities. Lambert’s work is exceptional and will appeal to a wide audience.