The spread of COVID-19, and the world's response to it, has its roots in many different histories: the history of trade, travel, and globalization; the history of medicine and public health; the history of governance and how citizens respond to it. This month, historian Donald Worster puts the pandemic in the deep history of human interaction with the natural world, especially agriculture. He argues that Covid-19 is part of a long pattern of unintended consequences that result when humans have transformed the environment and the other species around us.

An eerie silence fell over the world’s cities and towns this spring, as governments ordered their citizens to stay home, avoid unnecessary travel, and keep away from large-group gatherings. Urban streets, rural highways, brand-new airports, and the new generation of bullet trains are all emptier than before, for they are the dreaded paths that the coronavirus (COVID-19 or SARS- Cov2) takes to spread from continent to continent and reach its next victims.

Other plant and animal species began returning to our cities, making a rather unfamiliar noise with their singing and honking. That clamor of geese, woodpeckers, and swans came from a set of tough and adaptive survivors of a general holocaust that animal species have been going through.

They represent the few who have survived, but they should not be taken as signs of a general planetary recovery. That process may take thousands, even millions, of years. Industrial civilization, in contrast, will not take so long to recover.

The biologist and writer Rachel Carson opened her world-shaking 1962 book Silent Spring with “a fable for tomorrow”—a future when “some evil spell” had settled on our communities, when “mysterious maladies swept the flocks of chickens; the cattle and sheep sickened and died. Everywhere was a shadow of death.”

The cause of her imagined silence was pesticides like DDT, liberally applied to fields and lawns to eradicate the pests and vermin that threatened agricultural production—a production of food deemed necessary to feed a burgeoning human population and make money for corporations and farmers.

To combat spruce budworm outbreaks, DDT was sprayed liberally across the conifer forests throughout North America during the 1950s-1970s (left). An American soldier is sprayed with DDT during WWII (right).

Now, six decades later, DDT is no longer used in the United States, although many replacements have been invented and spread across the land. Throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America the old poison is still being used to combat insect pests and control diseases. China, for example, last year produced 4,500 metric tons of DDT to kill ticks and mites.

And worldwide more than 2.5 million metric tons of killer chemicals are being applied to the land each year. That drenching rain of poison has become much heavier than Carson ever imagined, and it continues to devastate the planet’s ecology.

Nor did Carson foresee the new kind of silence we are experiencing. It comes from a cessation of industrial civilization’s usual screeches and rumbles.

This time the cause is not a pesticide but a dangerous virus that has jumped from lower animals, where it first evolved, all the way up to humans.

Likely it started among bats and then may have jumped to pangolins, snakes, or bamboo rats, and then transferred to people buying meat in a poorly regulated “wet market” where meat from freshly killed animals is sold.

As I write, there are more than 25 million cases of COVID-19 infection worldwide—and that has happened in a mere six or seven months. We may have many more months to wait before a safe, effective vaccine is available. Thus, the silence spreading across our cities and countryside may grow until it has become a truly deafening silence, the kind that stops all rational thought.

Speaking of irrationality, some people are calling for nothing less than the mass extermination of the infecting species, just as they did when insects were seen as the great enemy and chlorinated hydrocarbons and organic phosphates became weapons in a war. Kill the Japanese beetles! Exterminate the Russian thistle!

A Delta Airlines employee disinfects the surfaces of the cabin including tray tables, seat backs, and in-flight entertainment screens in a Boeing 757, 2020. The sanitizing solution is the same solution used to sanitize hospitals nationwide.

Now the cry is to kill all the bats. Rid the world of all the viruses and bacteria. Drench the Earth with bleach baths, hand sanitizers, and vaccines. Save civilization from a dangerous, out of control nature. There is no shortage of noise when humans begin to panic and shout for revenge.

We humans are in a fighting mood, and the fight once more is against nature. The non-human world is being blamed not only for the current pandemic but also for the resulting upheaval in trade, manufacturing, transportation, jobs, currencies, stock prices, education, climate and biodiversity conferences, immigration, and hospitals.

“The People Had Done It Themselves”

Eventually, after the first waves of panic begin to subside, we may be open to a better understanding of why this epidemic has occurred. The causes go deeper in time than the new coronavirus itself. But right now the pandemic is intensifying our ancient fears of the natural world and stigmatizing other species as threats to our way of life. If that becomes a long-term consequence, then we will have seriously misunderstood what has happened and what needs to change.

“No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life,” Carson wrote at the end of her fable about a spring that never arrived. “The people had done it themselves.”

She meant that we should not blame simply some cabal of greedy capitalists or foreign militarists. All kinds of people, and lots and lots of them, were the ultimate killers. They were part of the biggest population boom in history, and to feed their babies they demanded more and more food and fiber. Then they waged a war on insects and fungi that, unintentionally, ended by devastating the whole web of life.

Making war on nature to save babies, ordinary humans threatened their own health as well as the health of the planet. (Carson linked rising cancer rates and other modern diseases to the new pesticides). The ultimate cause, therefore, was not concentrated economic power; it was a deeper and broader cultural drive, synonymous with civilization, to conquer nature.

While it was true that some powerful agribusiness companies had perfected the new agricultural chemicals, showing “no humility before the vast forces with which they tamper,” ordinary people bore some responsibility too.

An insect killing spray advertisement from the January 3rd, 1948 edition of Australian Women's Weekly (left). An advertisement from the April 5th, 1947 edition of the Sydney Morning Herald (right).

Millions of people had gladly bought and used those chemicals or otherwise supported their use. The domination of nature was what they commonly sought, and chaos was what they got.

So it is in the current pandemic. Once again it is, finally, all of us humans, anonymous or powerful, obscure or prominent, decent or bad, who have made the world sick. Once more we have done it ourselves. Is there anyone who is innocent of all responsibility?

Yet the media is noisy with ethical reductionists who want to fix all the blame on a few. There are super-nationalists in the United States and China, for example, who want to blame the virus on foreigners, competing with them for power and wealth.

But that cannot be the real story, for COVID-19 is only the latest in a long series of world-shaking epidemics, and at the origin of those epidemics have stood many different nations.

The oriental rat flea pictured is infected with the Yersinia pestis bacterium, which appears as a dark mass in the gut (left). A photo from a 1975 plague victim shows necrosis of the hand, a characteristic of a Yersinia pestis infection (right).

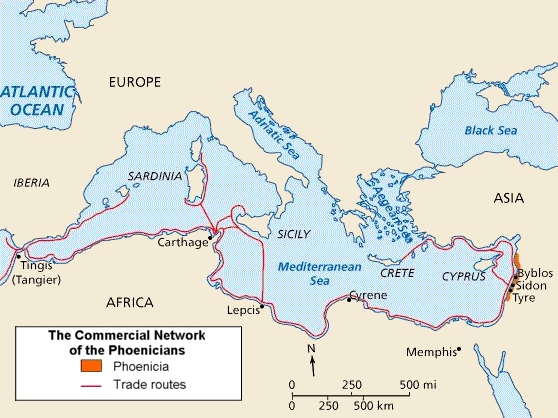

Take for example the Justinianic plague of the 6th-8th centuries CE, which killed half the population of Eurasia and northern Africa. Ground zero back then was the city of Constantinople, which had been infected by rodents carrying the bacterium Yersinia pestis (the same bacterium responsible for the Black Plague of 14th century Europe, which killed a third of the people).

Those outbreaks of “the plague” may have originated in central Asia or northern India, from whence unicellular micro-organisms were transported by desert caravans and trading ships, following the Silk Road or crossing the Black Sea, the Indian Ocean, and the Mediterranean Sea.

A similar international dispersal was repeated in the horror of 1918, when the virus H1N1 (misnamed the Spanish flu) emerged from the battlefields of World War I and killed 50 million people in all.

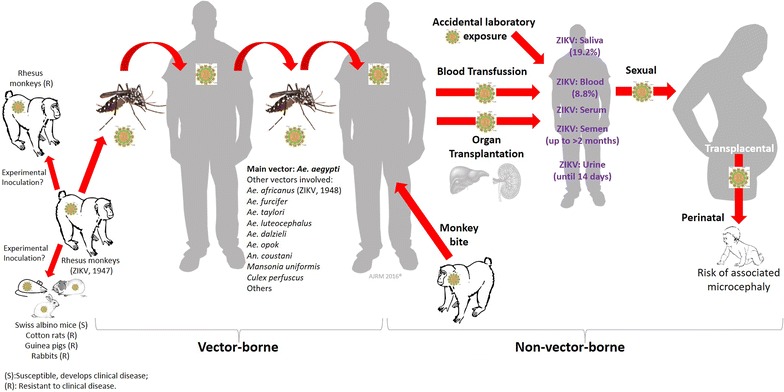

More recently brand-new epidemics have spread from a wide array of origins: Germany (the Marburg virus), Africa (Ebola, HIV), Latin America (Zika, dengue), North America (the Hanta virus), China (MERS-CoV, SARS CoV-2), and the United Kingdom (mad cow disease).

Clearly, there is no single “evil nation” behind all those epidemics. More sensibly, we should ask what the common cause behind them was.

The Human-Animal Relationship

Epidemics typically occur wherever and whenever human relations with animals go awry.

Therefore, we should look beyond our cities, factories, and hospitals to where most animals live—to the wild forests, grasslands, marshes and river valleys, or to farms large and small, including confined animal facilities (or feedlots) and subsistence homesteads carved by poor families out of a tropical forest.

Radical changes in wild and rural environments can make animals sick, and sick animals make people sick, though we may never touch or see them. Sick animals are not an enemy—they are victims much as we are. Nonetheless, they become scapegoats. That is why killing all the bats would neither be fair to bats nor make us healthier; it might even make things worse.

A growing number of biologists who study disease outbreaks are finding that in the majority of cases a local disturbance in ecological relations is the cause, with humans being the disturbing force. We make animals sick by altering their habitats and stressing their lives.

Usually this happens when people turn a wild ecosystem into a more simplified agricultural regime—or mining complex or network of highways. Complicated checks and balances get disrupted. Local diversity gets suppressed or lost. Viruses spread, mutate, and kill.

This process of ecological simplification began long before plant or animal domestication occurred on earth. Hunters and gatherers now and then unbalanced nature by killing off too many species or severely diminishing their numbers by overhunting.

The result was heavy stress for the surviving organisms. They had trouble reproducing and became more susceptible to bacterial and viral infections. Microorganisms, which had been relatively harmless and stable in their animal hosts, began to produce new mutants that earlier would have died but now thrived and reproduced, leading to microbial population explosions.

Unchecked population explosions indicate sickness. An animal already stressed by changes going on around it becomes vulnerable when strange new parasitic beings overwhelm its vital functions. Individuals die, species disappear, and the old ecosystem is gone. The new system is rampant with aggressive organisms that meet little resistance.

Agriculture and Disease

Then in human cultural evolution came agriculture, which intensified ecosystem disruption, as much as paving the land with asphalt would do to the soils. Agriculture is a process of choosing and rejecting, sometimes fairly gentle and moderate in impact but other times radical and violent. At either extreme the only selector is a single species looking for a more secure food supply, usually because of its own population stress.

An Egyptian hieroglyphic painting showing an early instance of a domesticated animal.

Farmers repeatedly mutate their methods and spread them as far as they can. Their favored species, those plants and animals that humans decide to raise in protected abundance, can themselves become more susceptible to disease than they were in the wild.

This happens when micro-organisms begin to concentrate more on the selected few, becoming parasites on domesticated livestock like cows, pigs, and chickens or crops like wheat, barley, and peas.

The farmer faces an epidemic that unwittingly he or she has made.

The process can be so slow and gradual that no individual, nor an entire village, can see the full implications. They see only the immediate threat of scarcity. Making the earth produce more food seems good for human offspring and for civilization, and surely it is so.

An aerial picture of cattle grazing land where forests used to be in northern Paraguay, 2008.

Today more than ever before, agriculture is the biggest single cause of declining biodiversity and species extinction on the planet.

It is turning old, relatively harmless, and remotely located viruses into dangerous predators, living on a narrowing biotic spectrum. Eventually, a small number of microorganisms become many, and they find their best sources of survival, not in the barnyard nor among wild animal populations, but among our own kind.

COVID-19 is spreading simply because there are so many of us. The bats are not so appealing.

Agriculture is the foundation of civilization, and it is those two cultural innovations that explain why epidemics have repeatedly swept the earth. Agricultural settlements began to trade, and trade spread those viral mutations from invaded, damaged ecosystems far and wide, far from the farmer’s understanding or ability to manage.

Before there was agriculture, to be sure, sickness occurred and spread among species, for wild, unmanaged nature has never been a perfectly stable set of bio-relations. Atmospheric and geological forces older than life have repeatedly disturbed ecosystems.

But the general tendency of ecosystems has been to moderate disturbances caused by inorganic forces and to stabilize populations of all organisms, including bacteria and viruses, and prevent any one of them from runaway domination.

Particularly with agriculture, humans became a disturbing force that, ironically, made their own survival both more secure (in terms of protein and other nutrients) and more uncertain.

They became more plagued by diseases than their foraging ancestors had been, although in recent centuries modern medicine has improved the odds for civilization, like dams and dikes protecting human settlements.

The diseases, however, even while generating more food and energy to sustain families and communities, have not stopped coming. We have been forced to make tradeoffs.

We have pursued agricultural innovation (most recently the Green Revolution) and demographic and economic growth, until now every continent’s ecology except Antarctica’s has been profoundly disrupted by human agriculture, and in return an abundance of crops flows endlessly to the cities.

It is a trade-off that on the whole has worked well for our kind. We now number nearly 8 billion, and 55 percent of us are able to live in towns, cities, and megalopolises because of an efficient world food system.

COVID-19 will not likely decrease our population much. Hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, may die, but in a single year or two we will multiply and replenish the earth again. But in this trade-off case there have been some gruesome costs, many injustices and severe collateral damage, and you or I may soon be among them.

Most of us remain ignorant of the tangled consequences of our way of life. Ignorance characterizes our cities as much as the countryside. It characterizes many university professors, corporate executives, and even experts in public health. They simply don’t think about disease in evolutionary and ecological terms, and thus they are doomed to repeat the same injustices and suffering experienced in the past.

The Questions We Need to Answer about COVID-19

Here in a few words is what we should ask about the ecological history of the most recent coronavirus. Where exactly did it originate?

We need to know not just the particular species involved (a mutant organism living within the horseshoe bat) but also the environmental conditions of its home place. We need, in other words, to do more than develop methods of self-protection. We need to understand the places from which diseases come and the eco-systemic changes they are going through.

How is climate change or land use change affecting the species living in that place? Have protein-hungry people been pushing in wild areas to capture “bush meat,” or to expand agriculture, and are they doing so in unprecedented numbers? What are the demographics of the local human population? What impact have population growth, markets, and the money economy had on formerly isolated places?

In the case of COVID-19 have virus reservoirs like bats been under siege? Are the other animals living in that place suffering from increased stress? What evidence do we have about their physical and mental condition? Are they getting sicker than usual, and thus carrying more and new pathogens in their bodies? Has species diversity diminished? Are viral mutations occurring that are adaptive to changing conditions?

A wild game stall at a Chinese market, 2007.

How have sickened animals and their load of microorganisms managed to get all the way to a city like Wuhan or New York? Once there, how have they been mixed in with other animals, tame and wild, living in tightly confined quarters, and how has their excrement loaded with toxins mixed with that of other animals? Why are they not in their native habitat? Is it because of basic, genuine hunger among people, or because of cultural traditions that celebrate “wild meat” as a boost to health and virility?

Why has the coronavirus transferred so quickly to people—because we too are living more closely together, but also enjoying greater freedom to move across continents and the planet?

Above all, what can we do to right the balance of nature? How can we prevent the destabilizing effects of climate change and protect biodiversity? How can a new understanding of history, one more informed by ecology and evolution science, help us craft more knowledgeable and effective strategies for our own survival?

“There’s Only One Health”

The core challenge presented by COVID-19 is how we humans can restore and protect the health, not just of ourselves, but also of the planet.

As William Karesh of the Eco-Health Alliance puts it, “There’s only one health.” If we focus only on the healthiness of our human lives and economy, we will fail again and again to keep either the planet or ourselves healthy.

To reach that understanding we need to accept one basic truth: We humans are by origin and by nature animals too. What we do to our fellow creatures, intentionally or not, can bounce back to hit us in the lungs or liver.

This means acknowledging the blamelessness of the nonhuman agents in this tragedy. Viruses and bacteria may become dreaded killing agents, but they are not guilty of any evil or crime.

A virus is neither plant nor animal; it is a boundary organism, dating back to the origins of life on the planet. Its nature is to live as a parasite. It has no moral consciousness, and therefore cannot rationally be singled out as our enemy. If we tried to exterminate all the viruses on earth, we would not be healthier but rather living more precariously than ever.

And after all, we humans are only a more complicated kind of virus. Viruses “want” only one thing: to find a host, grow, reproduce, and spread. How is that different from what humans want?

We want to reproduce and increase our numbers, and the way we do that is to become parasites ourselves, sucking the life out of the planet for our growth. It is precisely because of our deeply, essentially biological nature that we find ourselves victims.

The way to more security is to preserve and enhance the checks and balances nature has evolved. A more stable state of health requires better knowledge, a more intact web of life, and a lot more wilderness.

That was Rachel Carson’s message at the dawn of the age of ecology: We can be safe and healthy only when the whole planet is safe and healthy and well- balanced among competing populations.

Earlier versions of this article were published in Mandarin in 中華讀書報 (China Reading Weekly) and in English as “Another Silent Spring.” Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2020, no. 1 (22 April 2020). Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9028.

Read, Listen to, and Watch more from Origins on Pandemics and Coronavirus.

Among the many scientists writing about the ecology and evolutionary history of disease, I recommend particularly the publications of Professor Kate Jones of the University College of London. They include “Impacts of Biodiversity on the Emergence and Transmission of Infectious Diseases” (co-authored with Felicia Keesing et al.), Nature 468 (December 2, 2010): 647-652; and “Global Trends in Emerging Infectious Diseases,” Nature, 451 (February 21, 2008): 990. Also see Sarah Zohdy, Tonia S. Schwartz, and Jamie R. Oaks, “The Coevolution Effect as a Driver of Spillover,” Trends in Parasitology 35 (June 2019): 399-408; John Vidal, “'Tip of the Iceberg': Is Our Destruction of Nature Responsible for Covid-19?” The Guardian (March 18, 2020); United Nations Environment Programme and International Livestock Research Institute, Preventing the Next Pandemic: Zoonotic Diseases and How to Break the Chain of Transmission (Nairobi, Kenya: 2020); William B. Karesh and Robert A. Cook, “One World—One Health,” Clinical Medicine (2009): 259-60; and David Quammen, Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012).