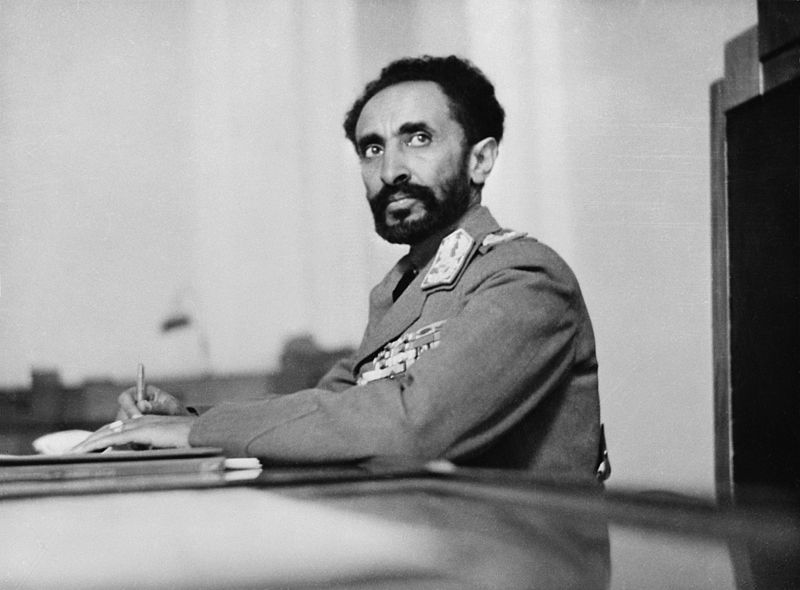

On May 5, 1941, Haile Selassie I returned triumphantly to his beloved capital city, Addis Ababa. The Ethiopian Emperor was accompanied by battle-tested companies of Patriot guerilla fighters (the Arbanyoch). British Colonel Orde Wingate led Gideon Force and an assorted mix of Commonwealth fighters from Egypt, Sudan, and Kenya. Enormous feasts and festivities followed the re‐establishment of the Solomonic Dynasty and a sovereign Ethiopia.

World War II was still in its early years. The United States had not yet joined the Allies, as it would do on December 8, 1941. But Italy had joined the Axis powers, so the United Kingdom had reason to help Ethiopia.

The date Haile Selassie chose to re-enter his capital was heavy with symbolism. Exactly five years before, on May 5, 1936, the Italian Army moved into the capital of Ethiopia, with their dreams of Africa Orientale Italiana. This was the second time Italy had sent their forces to Ethiopia. The first invasion happened in 1896 at the Battle of Adwa, where Italy suffered defeat—a wound that festered as the “Adwa complex” and became the basis for Mussolini’s promise in the 1920s of a racial and manly redemption.

Italy and Ethiopia were members of the League of Nations. They had signed treaties of friendship. So Mussolini needed a pretext for war. This came at a remote oasis in the Ogaden Desert known as Walwal where, on December 5, 1934, there was a border skirmish in which 21 Italians and 107 Ethiopians were killed.

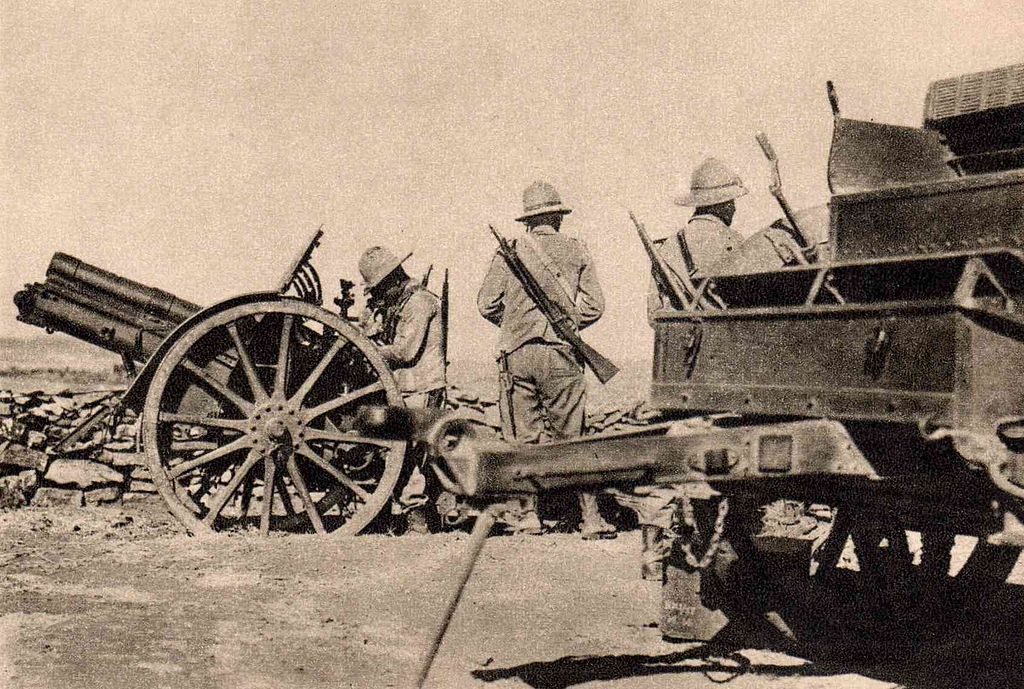

Even though an international team had established that Walwal was in fact 150 kilometers within Ethiopian territory, three Italian army corps invaded Ethiopia from Eritrea on October 3, 1935. Included in their arsenal were 156 assault tanks and 126 airplanes. Another Italian army corps crossed the Ethiopian border from Italian Somaliland.

Italian artilery during a battle with Ethiopia in 1936

The decisive factor in a series of battle victories in 1935 and 1936 was Italy’s use of poison gas, delivered by airplanes in both canister and spray form against Ethiopian military and civilian populations.

This use of chemicals violated the international treaty of Montreux, which Italy had signed in 1928, as part of a series of treaties that would collectively be known as the Geneva Conventions.

It is estimated that about 4‐5% of the Ethiopian population of 12 million people lost their lives during the second Italian occupation. Among the dead were members of the aristocracy, much of the intelligentsia, and priests and deacons from the Debra Libanos monastery.

Forced into exile in England to preserve a government in absentia, Haile Selassie made an eloquent defense of his country’s independence at the League of Nations on June 1, 1936: “I declare in the face of the whole world that the Emperor, the Government and the people of Ethiopia will not bow before force; that they maintain their claims that they will use all means in their power to ensure the triumph of right and the respect of the Covenant.”

In 1940, Italy joined Japan and Germany in the Tripartite Treaty. Now Britain was a formal enemy of Ethiopia’s would‐be colonizers, and thus friends of Haile Selassie, who represented the best opportunity to rally Ethiopia to its own defense. When he returned to Addis Ababa on May 5, therefore, Haile Selassie wanted to erase the humiliation of Ethiopia’s defeat 5 years earlier and replace it with a day for Ethiopians to celebrate.

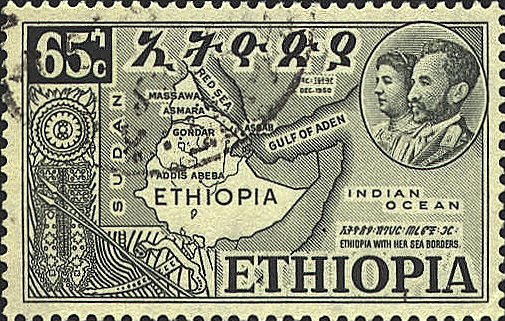

After the end of the war, under the United Nations mandate, the former colony of Eritrea became an autonomous region within the Ethiopian Federation. Haile Selassie had not only retained Ethiopia’s cherished independence but also restored access to the Red Sea. In 1963 Haile Selassie became the first president of the Organization of African Unity, located in Addis Ababa.

Ethiopia did not escape the negative effects of Italy’s attempted colonization and the postwar decades have proven violent and fracturing to Ethiopians. In his memoirs Haile Selassie noted that the Italian occupation set back by many years his own efforts to modernize Ethiopia. In 1961, an Eritrean independence movement began which would lead to a Civil War that would cost more than one million lives and result, in 1993, in Ethiopia’s loss of Eritrea and its Red Sea access. In the 1970s Ethiopia won a war with Somalia over control of the Ogaden. In 1974, after Emperor Haile Selassie was overthrown in a military coup, Ethiopia entered a time of turmoil and suffering.

Which to remember first? Haile Selassie’s triumphant return to a sovereign Ethiopia on May 5, 1941, or Italy’s second invasion of Ethiopia, on the same date, five years before? The world’s weak response to Ethiopia’s call for help was a fatal mistake for the League of Nations and a turning point in World War II. But Haile Selassie’s triumphant return also signaled the rise of a new post‐colonial era in African history.