The logo for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

On September 2, 1998, the first conviction for the crime of genocide was entered by an international tribunal. The date is an essential milestone in the development of criminal responsibility imposed by the international community for the commission of mass atrocities.

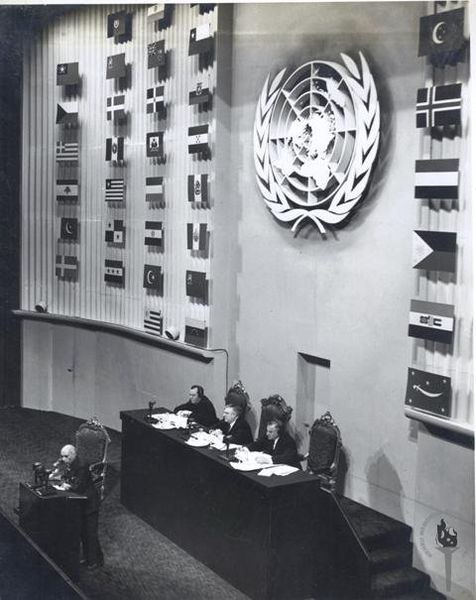

Yet, genocide became an international crime much earlier. One of the United Nations’ first acts after it was formed in 1945 was to draft the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, a framework for criminal trials at the international level for the commission of genocide.

The Convention said that trials should be conducted “by such international penal tribunal as may have jurisdiction.” The United Nations finalized the text of the Convention in 1948 and it entered into legal force in 1951 after the requisite number of states signed on.

At that time, however, there was no “international penal tribunal” that could try an individual for genocide. Not until four decades later, following atrocities committed in the former Yugoslavia and in Rwanda, were such tribunals set up in 1993 and 1994 respectively. These tribunals had jurisdiction only in these two locations, so they did not cover genocide committed elsewhere.

The Security Council wrote a statute that defined each tribunal’s powers and described the scope of its jurisdiction. Each statute defined genocide along with crimes against humanity and war crimes. Importantly, genocide was defined in the same terms as in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. Thus, for the first time humanity had tribunals that qualified as an “international penal tribunal” under the Convention.

On September 2, 1998, Jean-Paul Akayesu, mayor of a Rwandan town, became the first person convicted of genocide by either tribunal.

The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda found that local residents identified as ethnically Tutsi gathered near the mayor’s office for protection as mob violence against them intensified. Instead of safety, these residents were subjected to assault, rape, and murder by mobs that had gathered. Akayesu, who was at the office, did not act to prevent these assaults but instead encouraged and facilitated them.

A map of Rwanda (left). Jean-Paul Akayesu during his trial in 1998 (right). (Photo by ICTR)

Akayesu’s conviction and the existence of the two tribunals were also important in prompting the creation of an international tribunal with a broader competence. Why, UN leaders asked, should international criminal responsibility obtain only for atrocities committed in former Yugoslavia or Rwanda but not elsewhere?

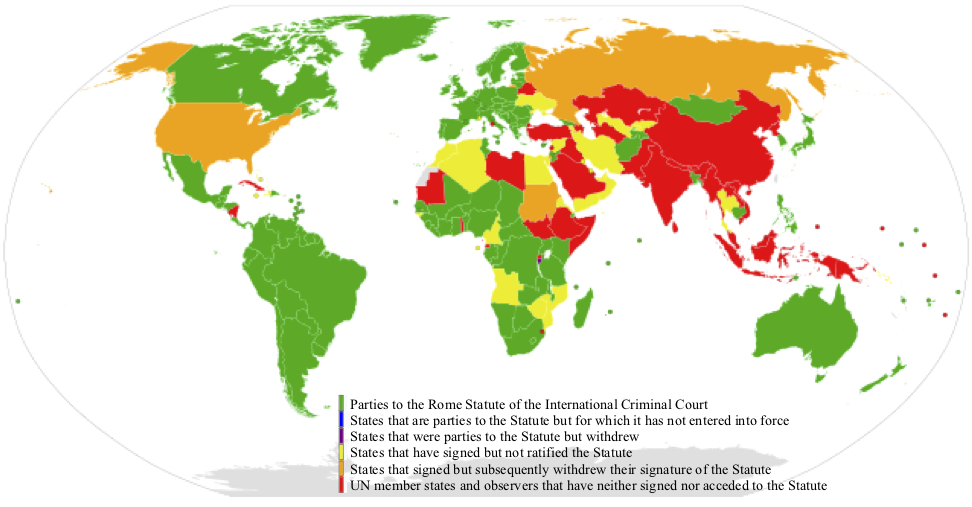

In 1998, the same year as Akayesu’s conviction, a United Nations conference met in Rome to draft a treaty for an international criminal tribunal that would have jurisdiction on a worldwide basis. The resulting treaty, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, covered genocide along with crimes against humanity and war crimes on a worldwide basis.

A celebration of the adoption of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court in 1998.

Parties and signatories of the Rome Statute.

The International Court has been recognized by 123 countries, giving it jurisdiction over genocide committed in the territory of those countries, or, anywhere, by nationals of those countries. Significantly, however, China, Russia, and the United States are not parties to the Rome Statute. Their absence limits the effectiveness of international criminal responsibility for genocide.

The International Criminal Court began functioning at headquarters in The Hague in the Netherlands in 2002. Although it has jurisdiction over genocide, it has focused more often on war crimes or crimes against humanity.

A building for the International Criminal Tribunal in Rwanda.

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defined genocide in a way that imposes a significant burden on the prosecution. For genocide, not only must assaults or killings or other acts have been committed that threaten the existence of a group, but they must have been committed with the intent to destroy the group. As of 2024, genocide has been charged in the International Criminal Court, but no one has been convicted of it yet.

The Akayesu case showed that international criminal responsibility for genocide raises complex issues. Akayesu’s case involved no direct killing or other atrocities by him. He was convicted for promoting murders and other brutalities by other persons. What in law is called mens rea, or criminal intent, had to be defined and elaborated for international tribunals.

A Catholic church in Ntarama, Rwanda where 5,000 people seeking refuge in 1994 were brutally killed.

Skulls from genocide victims at a memorial site in Rwanda.

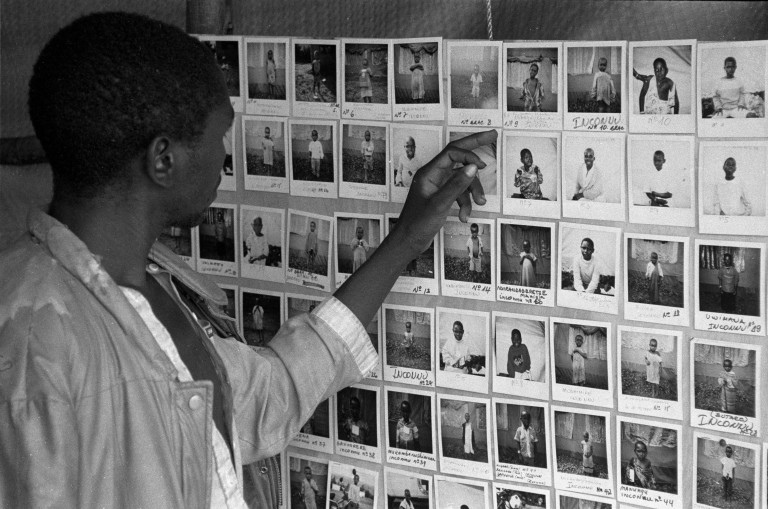

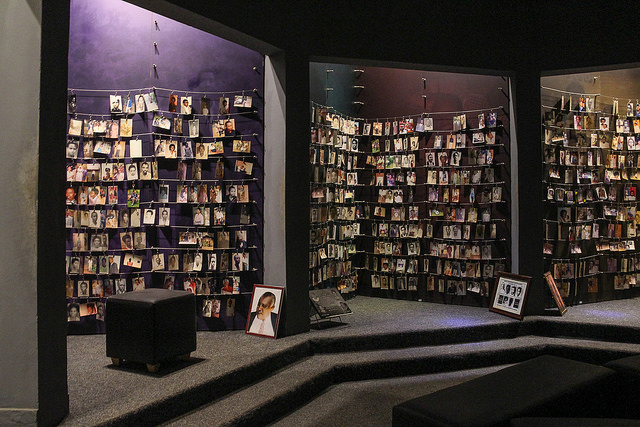

Pictures of victims at the Kigli Genocide Memorial Center in Rwanda. (Photo by travelmag.com)

Akayesu’s trial and the other trials held at that time required the development of a whole set of protections for the accused comparable to what is afforded to persons accused of crime in national courts globally.

Instead of a jury, a panel of three judges decided the Yugoslavia and Rwanda cases, with conviction possible by a vote of only two of the three. The same procedure has been adopted by the International Criminal Court, leading some critics to object that protection for the accused is insufficient.

The conviction of Akayesu on September 2, 1998 was a significant step in the development of international responsibility for genocide. Akayesu’s conviction sent a signal that humanity as a whole does not accept such barbarism. And people who engage in genocide may now be subjected to the process of justice.