Many Americans would identify their country as a "democracy." School children pledge their allegiance to the American flag and "to the Republic for which it stands." So which is it: Democracy or Republic? This month historian Lindsay Schakenbach-Regele explores the history of this distinction and what's at stake in the difference.

Civics quiz: Is and was the United States a) a democracy b) a republic c) both d) neither?

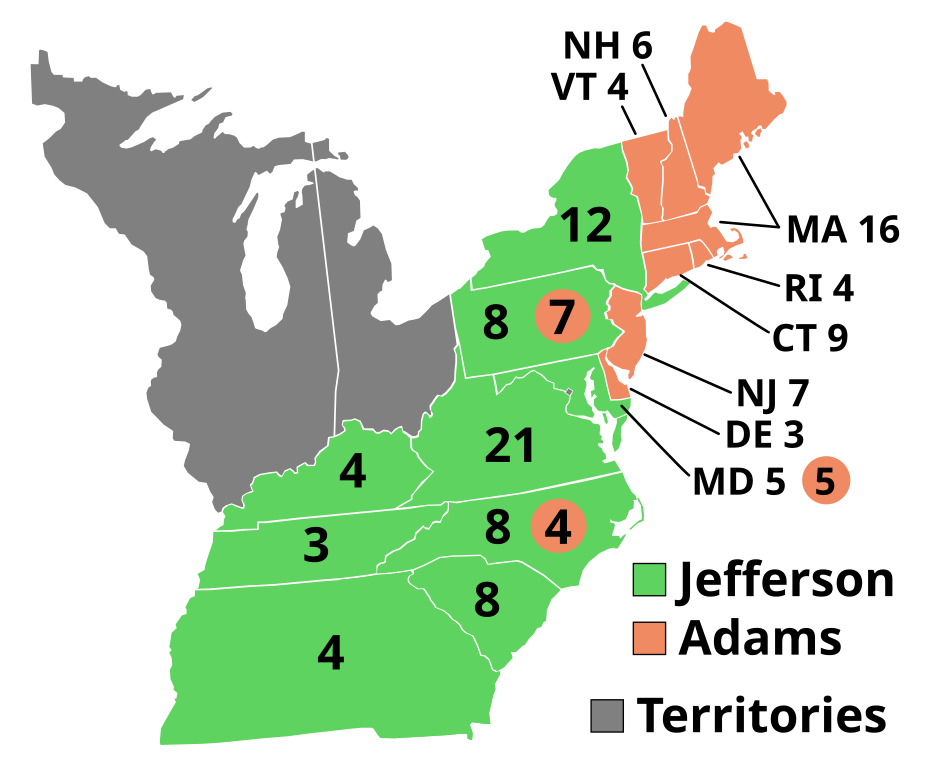

The answer depends on who you ask and when. In 2000, democracy – rule of the majority – lost out when Al Gore won the popular vote but lost the election by one electoral vote. It happened again in 2016 when Hilary Clinton won almost 2.9 million more votes than Donald Trump.

When he was asked last year if democracy is the most effective form of government, Donald Trump said, “I do.” (He then stated opaquely, “I don’t consider us to have much of a democracy right now.”)

When Vice President Kamala Harris accepted the nomination at the Democratic National Convention, she said, “In the enduring struggle between democracy and tyranny, I know where I stand. And I know where the United States belongs.”

To listen to both presidential candidates in 2024, it would seem that the answer we should all want to be correct is democracy. Indeed, a 2023 Pew Research Poll found that large majorities of both Republicans and Democrats say their party “respects the country’s democratic institutions and traditions.”

Yet, according to some Republican politicians, like House Speaker Mike Johnson, and many Trump supporters, the United States is definitely not, nor should it try to be, a democracy. He would probably pick “b”: a republic.

When the United States became a nation, “democracy” was not usually a good thing. It implied mob rule and tyranny by a dangerous majority, a fate perhaps worse than rule by a king. A republic, on the other hand, offered the perfect antidote to monarchy.

A republic would be built on the principles of “republicanism,” a set of virtues that in the 18th century included the selflessness to put the common good above special interests. Only a few (men) could be trusted to vote in this way; even fewer had the necessary republican virtues to govern. In the first presidential election in 1789, only 28,000 men voted in a population of roughly 3 million (2.4 free people and 600,000 enslaved).

By the early nineteenth century, however, the label “democrat” was claimed by members of one of the nation’s first two political parties. Ever since, democracy and republicanism have coexisted, sometimes complementarily, other times confrontationally.

Part of the reason for this uneasiness is that since the middle of the nineteenth century, the two major political parties have adopted the terms “republican” and “democratic” in opposition to one another, yet neither is accurately descriptive. Additionally, the values of both parties have changed dramatically over time and in some ways have flip flopped.

We might ask ourselves: How did Americans get from a celebration of 18th century republicanism to Thomas Jefferson’s “Democratic-Republicans” within a decade? Why did the political party (Lincoln’s Republicans) that expanded democracy for black men violate both democratic and republican principles before, during, and after the Civil War? And how did we get to a place where Americans wearing red, white, and blue at a political rally proudly declare that the United States is not a democracy?

Republicanism at the Founding

Late eighteenth-century political culture was steeped in republicanism, which stems from the Latin phrase res publica, meaning “public thing.” Republican thought and polities originated in ancient Greece and Rome, reemerged among medieval Italian states and again among Dutch and Polish polities and the English country party, and then provided the ideological foundation for American independence throughout the western hemisphere.

Republicanism was in no way unique to what would become the United States: republicanism existed throughout the Americas – in British North America and Spanish Mexico, and South Americans who fought independence wars against their colonial rulers sought to establish a republican system of government somewhat akin to the classical Roman model.

These governments would rest on the consent of the governed, but, unlike in a democracy, the majority would not rule. Many of the U.S. founding fathers imagined a world in which social hierarchy would persist and the majority of voters would elect “virtuous” political elites to govern.

Democracy was often a pejorative word, and even Thomas Paine, who argued for a more democratic government (“radical democracy” according to critics) than most proponents of independence, rarely employed it.

The word democracy is nowhere in the Constitution (the word “republic” is), although the document did set up a federal system of representative democracy. When the delegates to the Constitutional Convention debated the structure of the new national government, they were concerned with creating a balanced form of government that could stave off both autocracy and pure democracy.

Over the course of several weeks, delegates discussed how to elect a chief magistrate: directly, through Congress, or by electors? A few delegates, namely Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts, believed the majority of citizens were too ignorant and ill-informed to make a selection, and would be easily manipulated. One solution was to have Congress elect a leader, but this stirred up fears of an all-powerful legislative branch. The solution was the electoral college process, although the term “electoral college” was not used in the Constitution and was not written into federal statutes until later in the 1800s.

Critics of the electoral college today rightly associate it with racism and enslavement: white slaveholders received disproportionate representation in Congress and in presidential elections because enslaved individuals could not vote, but as human property, they counted as three-fifths of a person, and thus increased their state’s number of congressional representatives and electors.

The electoral college is the reason four of the five first presidents were Virginia slaveholders. Oddly enough, however, three slaveholding states – Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina (a slave majority!) – were the only states to vote against having electors choose the president. This fact enables some scholars to argue that the electoral college was not designed to protect slavery.

Regardless of how much enslavers’ interests influenced the creation of the electoral college, the fact of the matter is that it limits democratic rule. Although it was not a fashionable word in the revolutionary era, democracy was still something that many Americans strove for, as evidenced by initial widespread support for French revolutionaries who fought for democracy.

The early 1790s saw steady increases in the usage of the word democracy, as Americans reacted to the French Revolution. Radical newspaper editors adopted the term in support of France’s revolutionaries, and political clubs with “democratic” in the name began to form in the 1790s, reclaiming a derogatory word to celebrate non-elite politics.

Jeffersonian and Jacksonian Democracy

That “democracy” was embraced so readily by Jefferson in his presidential campaigns underscores just how much its connotation had changed, and how quickly. Jefferson’s party – the Jeffersonian Republicans, the Democrat-Republicans, or simply the Republican party – celebrated democracy and political equality among white men.

While at the end of the day, Jefferson supported republican values above all else – believing that landowning, virtuous men were best suited to govern and that majority rule threatened individual liberties – he was more inclined toward democracy than his Federalist opponents.

As the Federalist Party became increasingly out of touch, all mainstream politicians began to associate with some version of the (Democratic) Republican Party. Partisanship melted into a so-called Era of Good Feelings at the end of the War of 1812.

To be clear, feelings were not all good, but the United States went almost a decade with only one viable political party. Underlying tensions led to the rise of the Second Party System, in which Andrew Jackson emerged as the white man’s champion of a democracy that was more populist than the Jeffersonian brand had been.

During Jackson’s presidency, participation of the common man in government was encouraged, and white male suffrage expanded as individual state property requirements were removed.

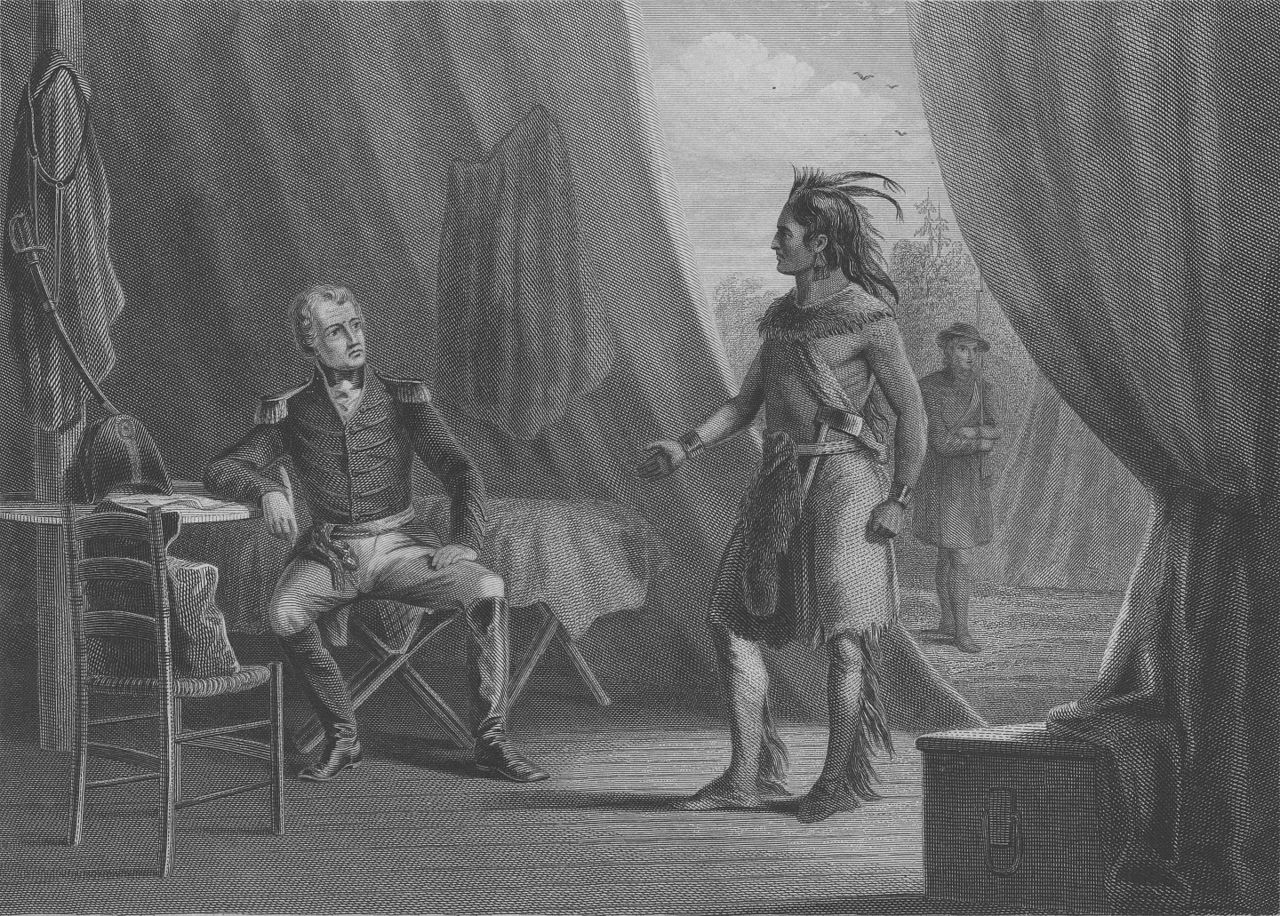

Critics of Jacksonian democracy have rightly pointed out that it was a sort of herrenvolk democracy – democracy restricted to one group only – and that universal white male suffrage was accompanied by enslavement, discrimination against nonwhites, and Native genocide.

For white men, democracy was more expansive than it had been before in the United States. In fact, it grew so expansive that new fears about the tyranny of the majority emerged.

To take one example, in the 1840s, many states instituted a process of popular referendum for issuing liquor licenses, which had previously been granted at the discretion of local administrative bodies. To some, especially temperance reformers, this new “local option” was evidence of the virtues of direct democracy.

Opponents, however, saw the local option as an example of tyranny of the majority, an attempt to violate minority rights (to consume alcohol) through legal coercion. Local option laws regarding alcohol and marijuana still exist in some places and, in general, direct democracy increased into the twentieth century.

Civil War and Reconstruction

As Jacksonian descendants championed popular democracy of the common white man and the right to own slaves, their opponents coalesced around a desire to combat the expansion of slavery, opposing the type of republic that permitted slavery.

Today’s two major political parties were born in these antebellum contests over the scope of democracy and republicanism The Democratic Party, the oldest active political party in the world, took its name in 1844, while the Republican Party adopted the Republican label in 1854 as a nod to Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans.

Each party contained internal inconsistencies. The Republican party opposed slavery as incompatible with democratic republics and touted the republican principle that a strong, unified republic was necessary to protect the rights and liberties of its citizens.

Yet in the eyes of many southerners, the party also violated major tenets of republicanism when its first president, Abraham Lincoln, took power without getting any votes in the southern states.

While Lincoln’s election adhered to the constitutional process, republicanism assumed representation of all states, and Lincoln's lack of support in the Southern states meant large portions of the population felt politically marginalized even within the framework of the Electoral College. The Republican party also suspended habeas corpus, imposed military rule in the former Confederate states, and disenfranchised many former Confederates.

Democrats, meanwhile, were preoccupied with preserving the legal status of slavery. These democrats defined the freedom to own human chattel as part of their individual liberty and saw abolition, therefore, as an attack on that liberty. The Democratic Party touted republican ideals in their opposition to what they saw as Constitutional violations and general centralized power, while they split in their ideas about democracy.

War Democrats saw the preservation of the Union as the key to protecting democracy, and Peace Democrats emphasized civil liberties, constitutional adherence, and states' rights as essential to a democratic society. Some of the goals of both factions were realized, but the party as a whole lost out to the Republican Party, which stayed in power for much of the next 60 years.

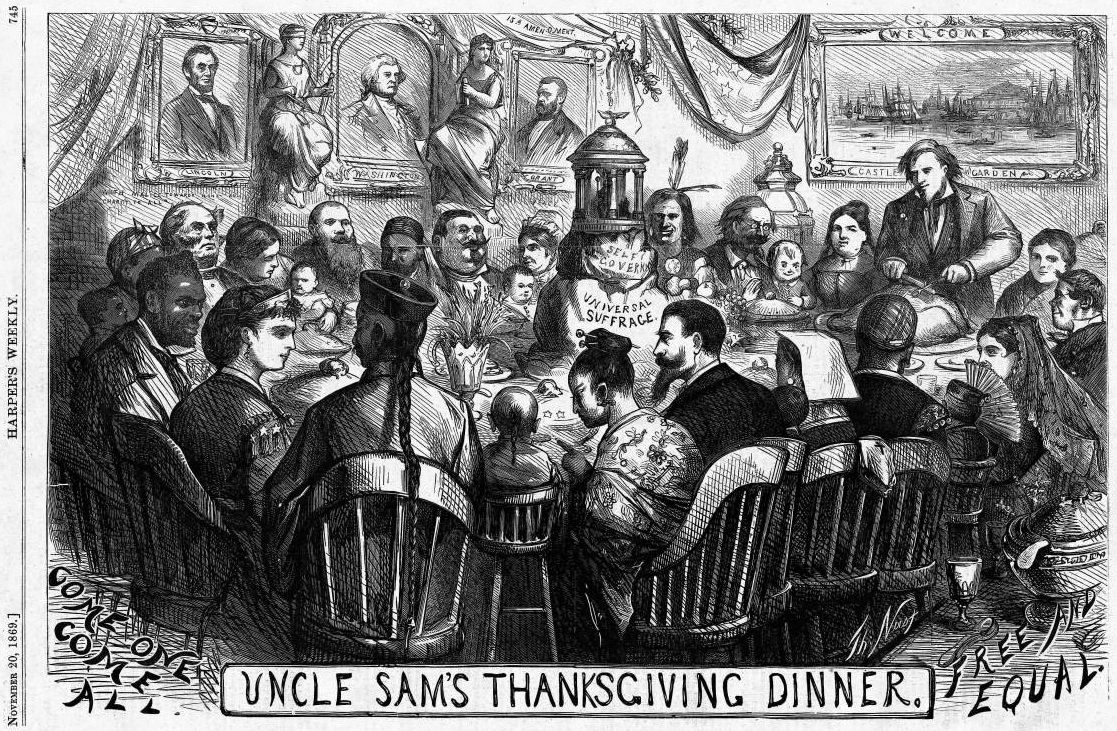

The tension between democracy and republicanism intensified following the war. The ratification of the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, which abolished slavery, established citizenship and protected rights for all persons born in the United States, and enfranchised Black men, respectively, represented democratic principles of equality and citizenship for African Americans.

Many white southerners, however, opposed this expanded democracy and saw it as leading to mob rule. In the name of state sovereignty, they violated those rights, often violently.

1877 marks the end of Reconstruction in most standard accounts of American history because it was the year federal troops stopped enforcing these civil rights amendments. That year also marked a battle against democracy.

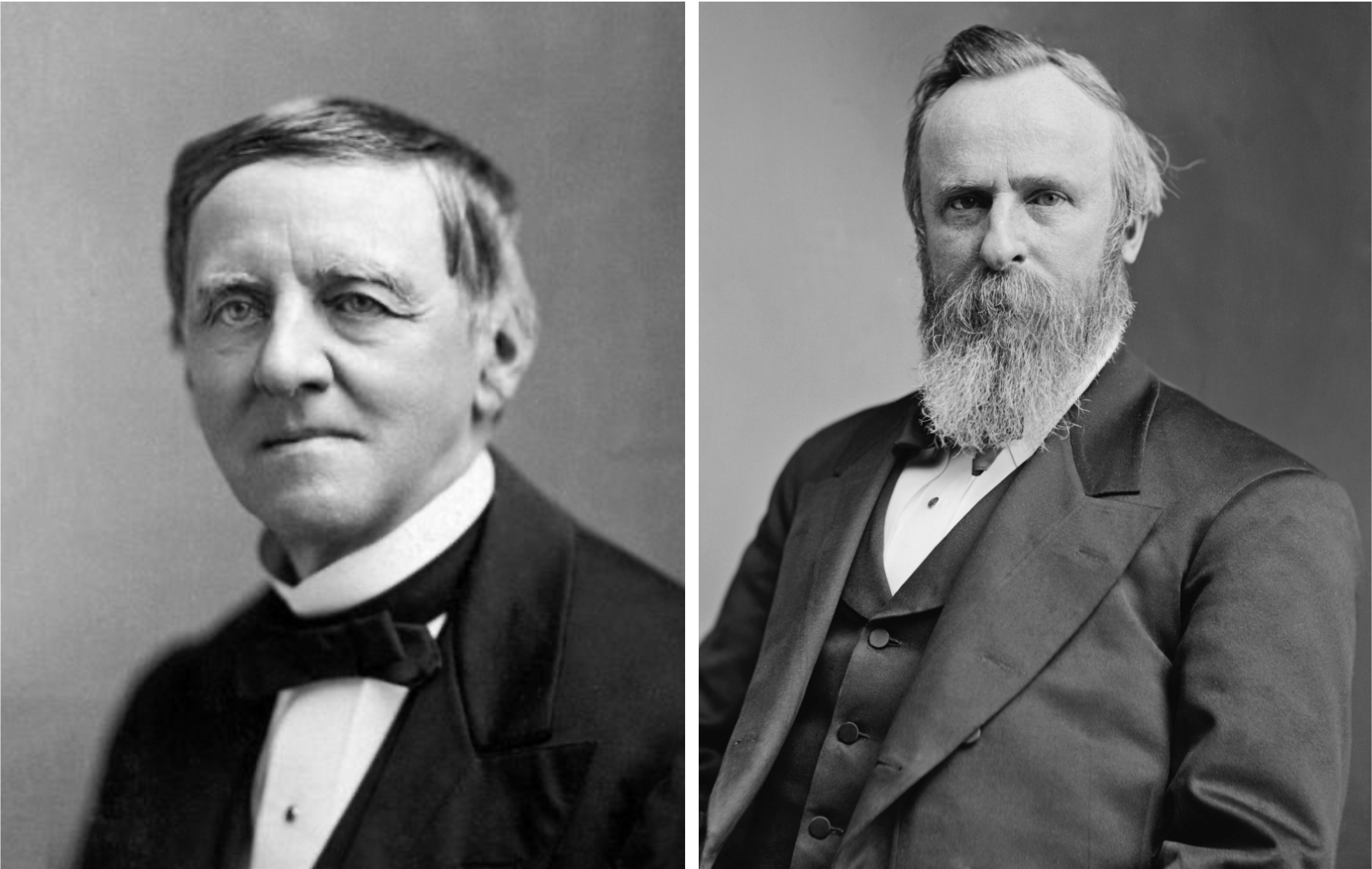

A “corrupt bargain” solved the disputed 1876 election, in which Samuel Tilden (Democrat) won the popular vote and received more electoral votes than Rutherford B. Hayes (Republican), but 20 disputed electoral votes from four states threw the election to the House. Hayes won after a special commission awarded him the disputed electoral votes. In exchange for the votes, Republicans agreed to stop enforcing Reconstruction policies.

The deal violated democratic principles on two fronts: it sidestepped the will of the people (Tilden’s popular vote victory), and it reversed democratic rights for African Americans because it permitted Southern states to institute discriminatory laws that disenfranchised Black voters.

Ultimately, the interests of a powerful minority were protected against a democracy they did not like.

“Progressive” Reforms?

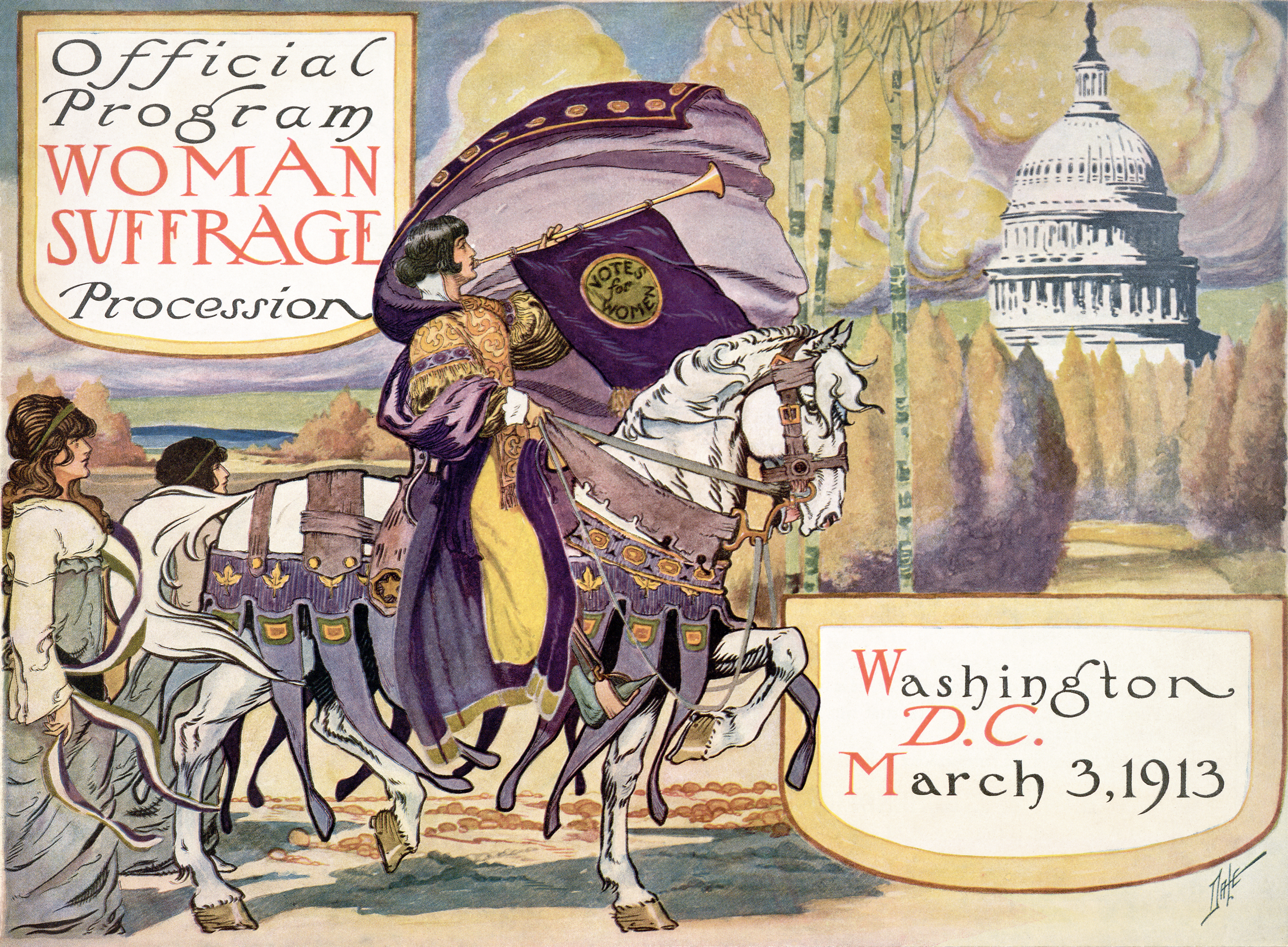

White women had long been considered important members of republican society—as keepers of virtue and mothers of citizen-soldiers. At the same time, however, the republicanism of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries mostly denied women –as legal dependents – the right to vote (except in New Jersey, where women could vote until 1807). There was a democratic push for universal suffrage until the fifteenth amendment denied women the right to vote.

Some women suffragists rallied around republican notions that only certain well-educated citizens be eligible to vote. Rather than wanting to expand democracy for all women nationwide, the suffragists splintered into groups that disagreed over whether voting rights were state-by-state or national and whether race and education qualified or disqualified someone from voting.

Ultimately, the 19th Amendment prohibited voting discrimination based on sex, an expansion of democracy that avoided elitist republican qualifications. At the state level, though, discrimination continued to occur based on both sex and race, in the form of literacy tests, poll taxes, and intimidation. These discriminatory measures reflected persistent republican notions that only some citizens were fit to make political decisions.

Democracy in the United States ebbs and flows. Take the election of senators.

Most of the men at the Constitutional Convention had agreed that there should be strong republican checks on those who served in Congress to limit the potential dangers of a democratic majority. They intended for senators to be immune to the whims of common voters, and so, until a constitutional amendment in 1913, they were elected by state legislatures, which made them the least democratically accountable elected officials.

Starting in the early 1800s, some congressmen sought to change the system, but movements for reform did not gain traction until Progressive reformers started speaking out against the elitism and corruption endemic to the process of electing senators.

While novels and other popular culture depicted senators as puppets and bargaining tools of powerful businessmen, states began calling for a convention to propose an amendment for the election of senators by voters. The seventeenth amendment gave power to the people at the expense of the state legislatures.

Debates about the seventeenth amendment and the election of senators continue into the 21st century. Opponents of the amendment claim it upsets the federalist balance of power and makes it difficult for senators to be held accountable to either the large populations they are supposed to represent or the state governments.

This tension has a long history.

The argument expressed in Federalist 62, defending the appointment of senators by the state legislatures against opponents who wanted a more transparent and democratic system of representation, is embodied in the rhetoric of some today, who want limits on democratic voting and who advocate for the right of states as a whole to influence elections.

A High-Water Mark and Its Backlash

There are efforts today to overturn the democratic gains made by the Voting Rights Act of 1965, legislation that simultaneously protected democratic rights and represented an affront to republicanism’s preference for state control of elections.

President Lyndon Johnson signed “An Act to enforce the fifteenth amendment of the Constitution of the United States, and for other purposes” into law on August 6, 1965. The law prohibited racial discrimination and outlawed literacy tests and other practices intended to disenfranchise minority voters. It was amended five times to expand its protections.

As part of Congress’s discussions on voting rights, the issue of lowering the minimum voting age from 21 (the norm nationwide) to 18 came up, with some arguing that it was undemocratic to force young men to serve in the Vietnam War without being able to vote.

The twenty-sixth amendment, proposed by Congress in March 1971 and ratified less than four months later, set the minimum voting age at eighteen in all local, state, and national elections. This marked a major shift in states’ previous ability to establish their own voting age.

The years between 1965 and 1975 marked a triumph of democracy, albeit one that bumped up against the tenets of republicanism. The protection and expansion of voting rights reduced the ability of states to determine voting qualifications.

The enfranchisement of younger voters brought up some of the founders’ old concerns about voters being virtuous citizens and stakeholders. And the democratic gains made by the civil rights movement prompted some to insist that the United States was a republic, not a democracy, and thus not everyone deserved to vote.

In 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelby County v. Holder that a key component of the Voting Rights Act, which prohibits states with histories of voter discrimination from making new voting laws without federal approval, is unconstitutional.

Since 2013, nearly a hundred new laws have restricted voting rights, many in states that were targeted by the 1965 act. These laws draw upon republicanism’s premise that not everyone is equally qualified for political representation, as new voter ID requirements disenfranchise thousands (Ohio has the strictest) and states like Georgia limit the number of ballot boxes in communities of color.

Who does the government represent and to whom are they accountable? The people. But who counts as the people and how the people’s votes are tallied up and weighted has always been and continues to be a contentious matter.

Carter, Katlyn Marie. "Denouncing Secrecy and Defining Democracy in the Early American Republic." Journal of the Early Republic 40, no. 3 (2020): 409-433. https://doi.org/10.1353/jer.2020.0063.

Lina de Castillo, Crafting a Republic for the World: Scientific, Geographic, and Historiographic Inventions of Colombia (University of Nebraska Press, 2018)

Seth Cotlar, “Languages of Democracy in America from the Revolution to the Election of 1800,” in Joanna Innes and Mark Philp, eds. Re-imagining Democracy in the Age of Revolutions: America, France, Britain, Ireland 1750-1850 (Oxford University Press, 2013).

Jefferson Cowie, Freedom’s Domain: A Saga of White Resistance To Federal Power. (New York: Basic Books, 2022).

Alex Gourevitch From Slavery to the Cooperative Commonwealth: Labor and Republican Liberty in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge University Press, 2014)

Kimberly Hamlin, Free Thinker: Sex, Suffrage, and the Extraordinary Life of Helen Hamilton Gardener, W.W. Norton, 2020

Jones, Martha. Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All (New York: Basic Books, 2020)

Levine, Bruce. “‘The Vital Element of the Republican Party’: Antislavery, Nativism, and Abraham Lincoln.” Journal of the Civil War Era 1, no. 4 (2011): 481–505.

Palmer, R. R. “Notes on the Use of the Word ‘Democracy’ 1789-1799.” Political Science Quarterly 68, no. 2 (1953): 203–26.

Kyle G. Volk, "The Perils of "Pure Democracy": Minority Rights, Liquor Politics, and Popular Sovereignty in Antebellum America." Journal of the Early Republic 29, no. 4 (2009): 641-679.