On the cold, foggy morning of January 21, 1793—225 years ago—French King Louis XVI made the hour and a half journey through the city of Paris from the Temple, the fortified medieval monastery where he was imprisoned, to the Place de la Révolution, where the scaffold for his execution was assembled.

Portrait of Louis XVI, King of France and Navarre, c. 1779.

He traveled in the mayor's coach accompanied by his confessor, Henry Essex Edgeworth de Firmont, and by Lieutenant Lebrasse. The Paris Commune, the revolutionary municipal government, had stationed guards four deep along the coach's path, and the journey passed mostly in silence as Louis prayed. By 10 am, Louis’ coach arrived peacefully at the Place de la Révolution, where some twenty thousand people had gathered.

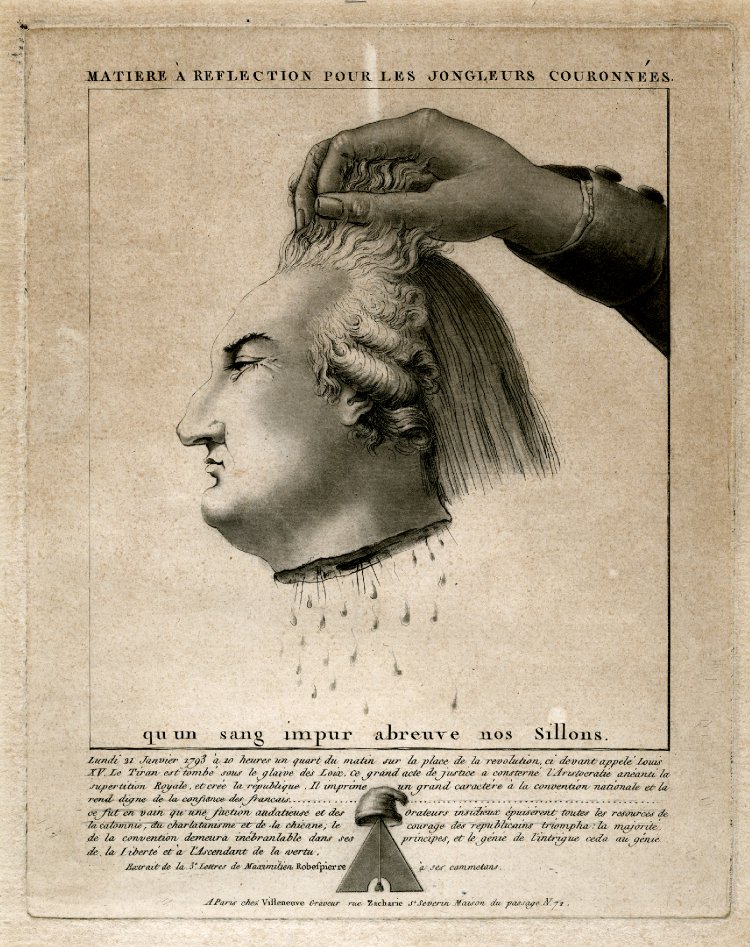

The coach approached the scaffold (which stood approximately where the Obelisk decorating the Place de la Concorde stands today). Louis dismounted the carriage and removed his coat and collar. The executioners bound his hands, led him up the stairs, and cut his hair.

Louis addressed the crowd in a clear voice, “I die innocent. I pardon my enemies and I hope that my blood will be useful to the French, that it will appease God’s anger...” At this point, the drums began to roll, and Louis’ final words were inaudible.

He was strapped to a plank, guided through the guillotine’s “widow's window,” and was executed. The execution of the king by his people was a transformative moment in European politics.

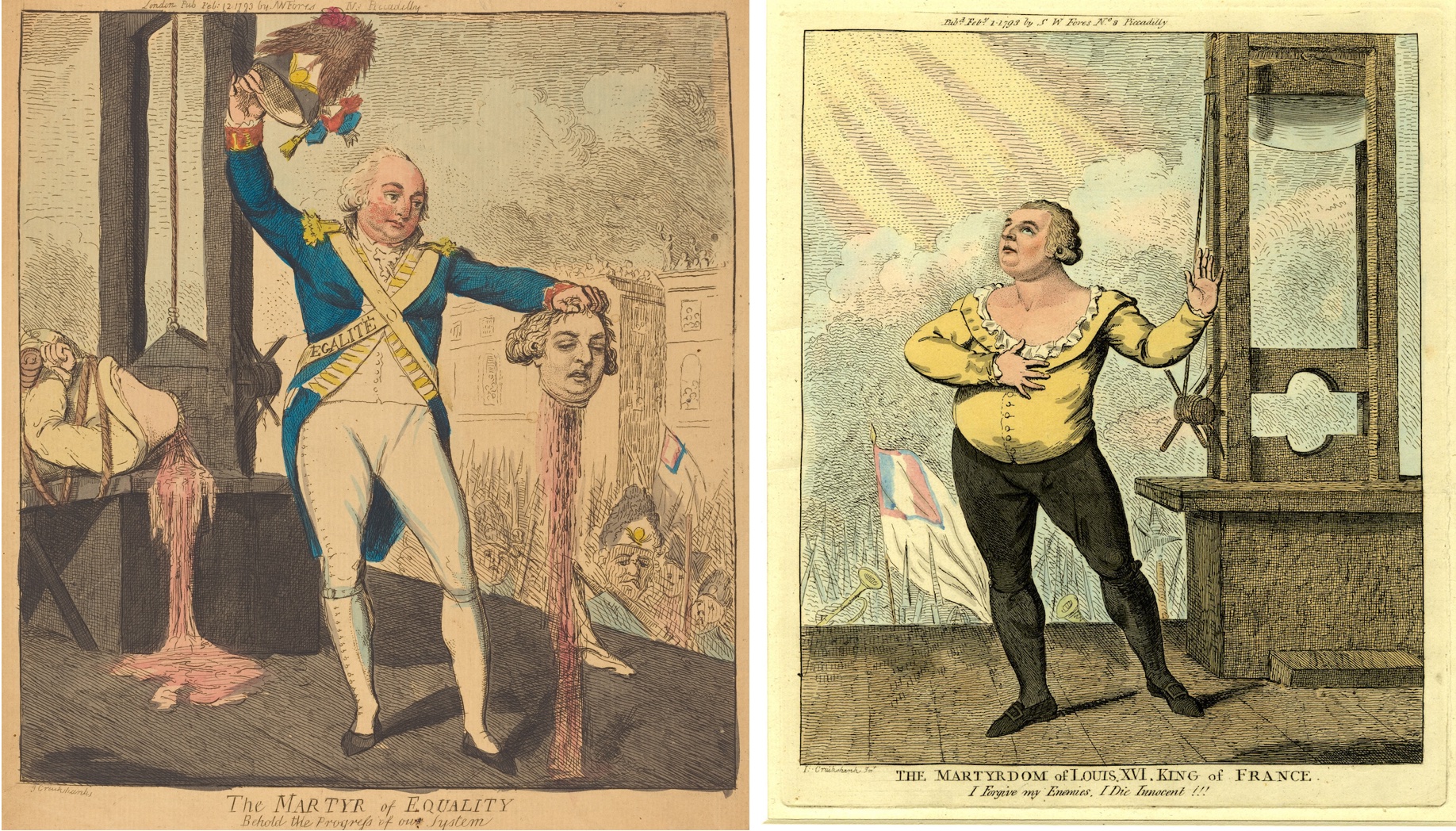

Illustrations of Louis XVI in the custody of French revolutionaries (The New York Public Library) (left), and his execution by guillotine in 1793 (Stanford University Libraries) (right).

Cries of “Long live the Republic” rang out. The crowd began to sing la Marseillaise, the song the soldiers of the Federated National Guard had brought with them to Paris the previous year. Some of those gathered pressed forward to dip their handkerchiefs in the blood of the king, which they kept as grisly souvenirs.

La Marseillaise, composed in 1792 by Claude-Joseph Rouget de Lisle.

All efforts were made to ensure that there would be nothing left of the king. Louis’ head and body were taken swiftly to the Madeleine Cemetery where he was buried in a deep grave in a wooden coffin, which was covered in quicklime to accelerate the decomposition process, and quickly covered over.

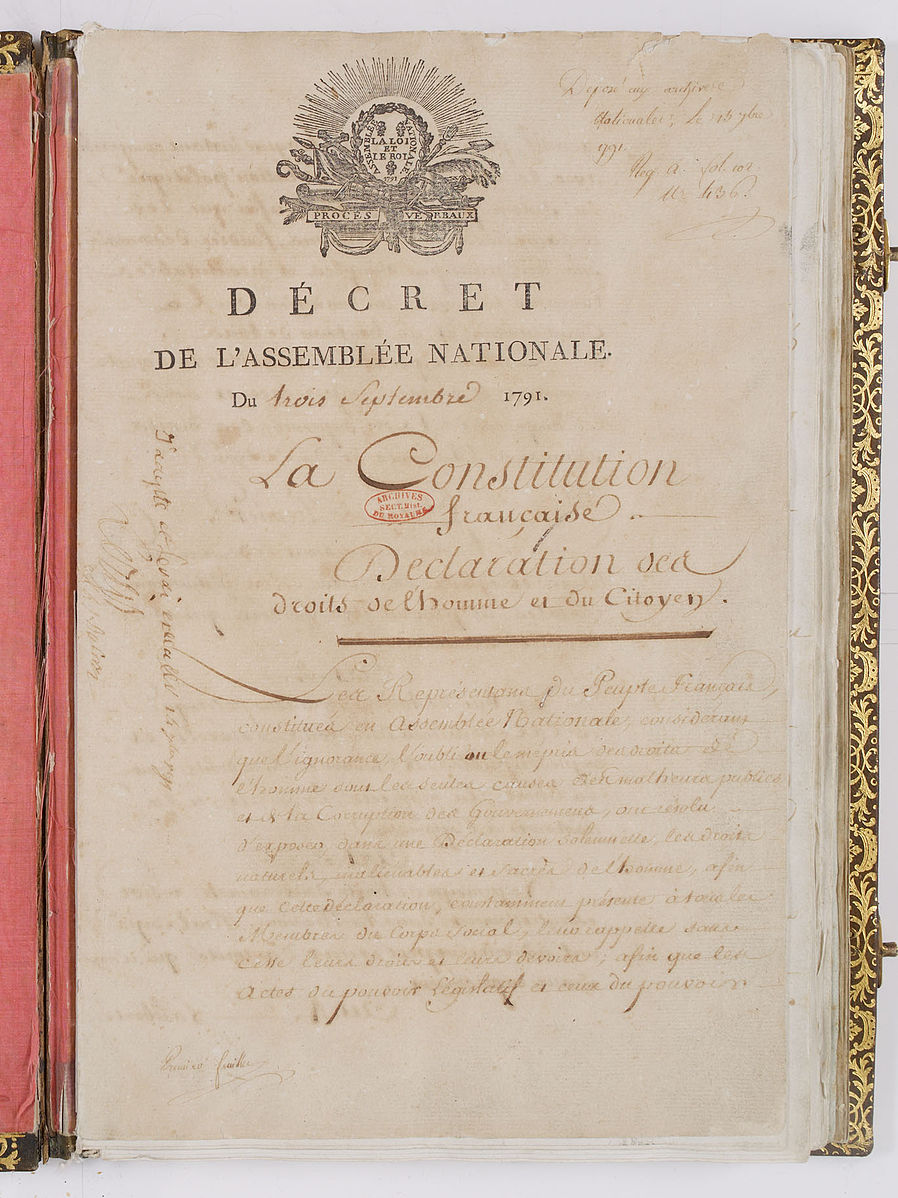

The French Constitution of 1791, which established a constitutional monarchy.

How had the French Revolution arrived at this moment? How did it become possible for the French to try and then to execute their beloved father, their king? After all, when the Revolution began just a few years before in 1789, no one could imagine a France without the king. The deputies of the National Assembly had advocated a constitutional monarchy, which they instituted in 1791.

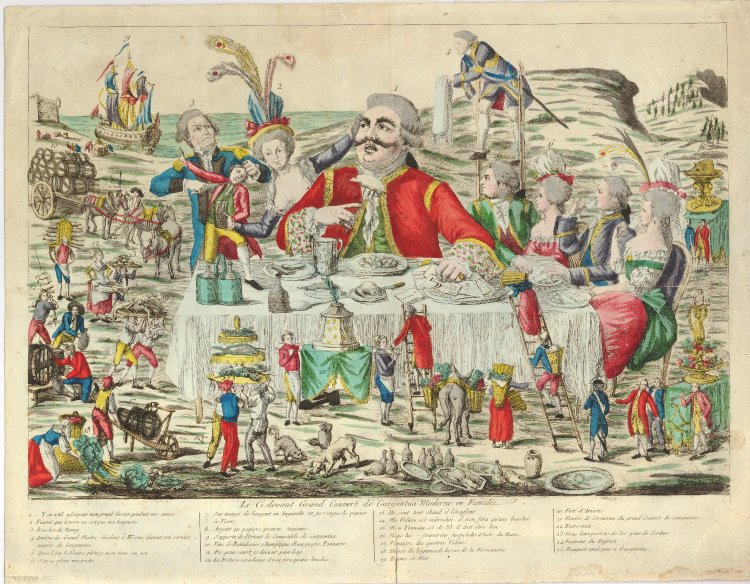

Critiques of Louis under the Old Regime and in the early years of the Revolution tended to portray Louis as a good king poorly advised. Events in the early years of the Revolution aligned with this view. Historians generally agree that Louis XVI was reform-minded and earnestly wanted the best for his people.

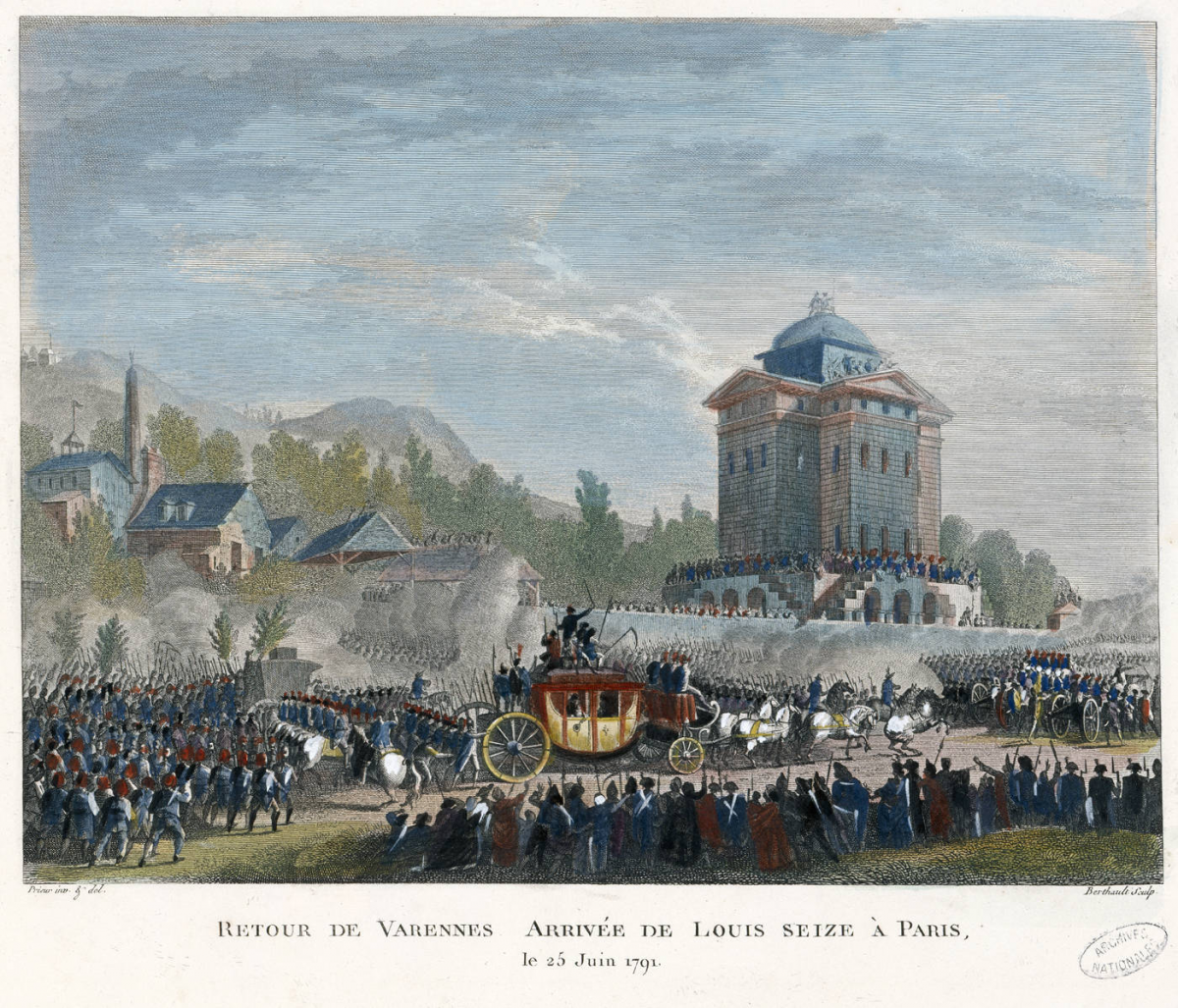

But the king had grown dissatisfied with the constraints of Constitutional Monarchy. In June 1791, he tried to escape Paris and flee to the Austrian Netherlands, where he could mount a resistance to the Revolution. Louis and his family very nearly made it, but they were recognized and arrested in the town of Varennes and escorted back to Paris by six thousand national guardsmen. As they made their way back to Paris, entire villages of armed men and women and children came out to meet the procession, to cheer the nation and harangue the king.

The flight to Varennes marked a turning point. The king had tried to abandon his people. Worse yet, Louis had left behind a letter in which he renounced the Revolution and claimed that all of his previous support for revolutionary legislation had been made under duress. He had lied; he had broken faith with his people.

The shift in public opinion was swift. Newspapers of a range of political positions critiqued and lampooned the king. Louis’ name, image, and insignias were removed from public view, like shop signs, inns, and other public buildings. The first sustained talk of a republic echoed through Paris in the weeks after the king’s attempted flight.

Satirical print reading “King Janus, or the man with two faces,” illustrating the shift in public opinion of Louis XVI after his flight to Varennes, 1791-1792 (Stanford University Libraries) (left), and a cartoon of the king wearing a revolutionary Phrygian cap and pretending to support the revolution, while secretly planning to launch a resistance against it, 1792 (right).

Caricature of Louis XVI’s face on a pig’s body, 1791. (Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The situation of the king deteriorated the following year.

By the summer of 1792, France was at war with Austria and Prussia, who were advancing swiftly into French territory. In August, the people of Paris and the national guardsmen began an insurrection, and Louis and his family were forced to flee the Tuileries Palace and seek the protection of the Legislative Assembly on August 10.

The Assembly initiated thorough and deliberate legal proceedings against the king, charging him with “a multitude of crimes to establish [his] tyranny,” including treason and counterrevolutionary activity.

Shortly before the trial began in December, more documents from a safe in the Tuileries palace were uncovered. The 625 documents in the armoire de fer provided evidence of Louis’ efforts over the past three years to destroy the Revolution: instructions for his ministers to lie to the Legislative Assembly, attempts to bribe deputies, and efforts to obstruct the constitution all appeared in the king's own hand.

A scene from the trial of Louis XVI.

Following the state’s case and the king’s defense, the deputies prepared to vote on three questions: the king’s guilt, his punishment, and whether the punishment should be put to a national referendum before it was carried out.

On January 15, 693 of the 745 deputies voted “yes” that the king was guilty. The deputies voted next on whether the punishment should be put to a national appeal, and 424 deputies voted against the appeal. The vote on the king’s death took place on January 16th, and the vote stretched late into the night and the following day.

Three hundred and sixty-one votes were needed for a simple majority and in the end 361 deputies voted unconditionally for death. The deputies entertained a series of appeals in the days following, but the measures to stay the king's execution failed. On January 20, 1793, the deputies decreed Louis’ guilt and his punishment by death; there would be no reprieve of his execution. The following day, the sentence against Louis was carried out.

Illustration of Louis XVI meeting with his family just before his execution on January 20, 1793.

In the years following Louis’ execution, the anniversary of his death was not celebrated. All but the most rudimentary facts of the king’s execution were omitted from the official record of the event. The memory of Louis was kept only by forces outside the French Republic. On June 17, 1793, the Catholic Church declared Louis XVI a “royal martyr.”

English cartoon criticizing the execution of Louis XVI, reading (left), and a British etching of Louis XVI just before his execution with the caption, “The martyrdom of Louis XVI King of France, 'I forgive my enemies. I die innocent!!!',” 1793 (British Royal Museum) (right).

Public celebrations in memory to Louis only returned to France when his younger brother retook the throne in 1814. On January 19, 1815, the king's remains were exhumed from the Madeleine and taken by convoy to the family crypt at the Saint-Denis cathedral where all but three French kings were buried.

The anniversary of Louis’ death was made a national day of mourning. At such memorial services, Louis’ will and testament was read aloud from the pulpit, sometimes instead of a sermon. These official celebrations lasted until the end of the Restoration period in 1830.

Under subsequent governments, individual French men and women were still free to mark the occasion of Louis’ death, though since the Second World War, such events have not been very popular beyond the small circle of monarchists in France.

Today, a requiem mass or memorial service for Louis is celebrated in many French cities and towns in the weeks surrounding January 21, often at the request of local royalist societies. The rather minimal support for memorials to Louis is a reminder of how incongruous the memory of the king is with French republican identity today. And it is a reminder of just how much the political structures of Europe have changed since that fateful execution day.

Bibliography for further reading:

David P. Jordan, The King’s Trial (all quotations in this article from Jordan)

Timothy Tackett, When the King took Flight

Michel Vovelle, “La Marseillaise: War or Peace” in Realms of Memory: The Construction of the French Past, ed. Pierre Nora, Vol. 3, Chapter 2.

On more recent celebrations in memory of Louis XVI:

http://www.nytimes.com/1993/01/22/world/paris-journal-it-s-a-little-late-but-still-bouquets-for-louis-xvi.html

https://www.messes-louisxvi.com/