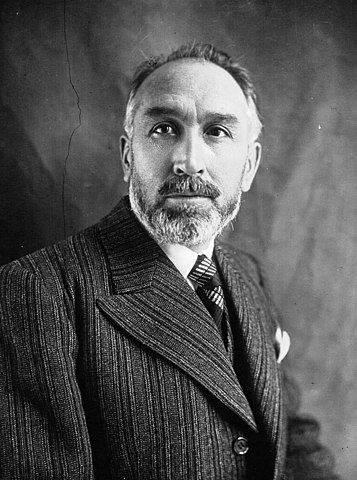

In the early morning hours of July 26, 1941, guests of the Relais de l’Empereur hotel in Montélimar, France were jolted from their sleep when a bomb exploded, taking the roof off of room #19 and ending the life of Marx Dormoy, former French Minister of the Interior and staunch opponent of France’s far right movements.

That right-wing terrorists—emboldened by the end of the Third Republic and new authoritarian leadership in France, dedicated to a conservative “National Revolution”—were to blame for the attack was hardly in question. The mystery was how high the plot went. Commissioner Charles Chenevier and Superintendent Georges Kubler of France’s investigative body, the Sûreté Nationale, were determined to find out. And so begins Brunelle and Finley-Croswhite’s Assassination in Vichy, like any good tale of murder and intrigue, with a crime scene and a mystery to solve.

In the Archives de Paris, documents related to the Marx Dormoy affair are nestled, appropriately, in and amongst papers related to the history of the Cagoule—an anti-communist terror organization founded by Eugène Deloncle to oppose the leftist Popular Front that governed France from 1936.

German soldiers parade on the Champs Élysées on June 14, 1940. Less than a month later, on July 10, 1940, the French National Assembly would vote to end the Third Republic and create the collaborationist French State, under Maréchal Phillipe Pétain.

As part of the Popular Front, Socialist deputy Dormoy rooted out and disbanded the Cagoule, though members soon regrouped as the Social Revolutionary Movement (MSR). When France signed an armistice with Nazi Germany on June 22, 1940 and little more than two weeks later voted 569 to 80 (with 12 abstentions) in the National Assembly to grant authoritarian powers to Maréchal Phillipe Pétain, former Cagoulards and sympathizers took up prominent places in the new French state.

Such men had not forgotten the gusto with which Dormoy had pursued them, nor did they forgive him for his vote against Pétain and the new government. The last years of Marx Dormoy’s life were thus intimately linked with the Cagoule. The investigation of his death and attempts to bring him justice posthumously were likewise shaped by the complex political landscape of wartime and postwar France.

Assassination in Vichy, then, is more than a history of the death of a man, it is the history of the life of a nation, and this was, unquestionably, the intention of the authors. They aim not just to resurrect Dormoy from relative obscurity but to “understand the motivations” of those involved in his death, and, in so doing, to illuminate the tangled history of wartime France, exposing it neither as a “nation of resisters” as Charles de Gaulle once claimed, nor, necessarily, as a nation of de-facto collaborators.

After introducing Dormoy and the crime itself, Assassination in Vichy proceeds more or less chronologically, following: the investigation (and the course of the Second World War, to which it was tied); the apprehension of the suspects (former Cagoulards Annie Mourraille, Yves Moynier, Ludovic Guichard and Roger Mouraille); the political battles with government authorities, the German occupiers, and their French collaborators that would see those responsible either freed or condemned; renewed efforts at prosecution in the postwar period; and, ultimately, the struggles over commemorating Dormoy’s battle with right-wing extremism in a country that would sooner forget that such battles had taken place.

As the authors write, “Dormoy was largely forgotten…because France needed to recover from the trauma of the war and construct a [favorable] consensus about French identity” (p. 219). Assassination in Vichy redresses this “selective amnesia” about the 1930s and 1940s, and it does so in an eminently readable fashion.

For decades reticence in France to confront fully wartime collaboration with Nazi Germany, and the rise of homegrown fascism in the 1930s, has hamstrung efforts to gain a rich and nuanced understanding of extremism in the period. This era, thankfully, is coming to a close.

As the authors note, far-right extremism has made an ominous return to the global stage. The invocation of “fake news,” a relic of twentieth-century fascist movements that has enjoyed a worrying resurgence in our own time, provides a short-hand alert to the contemporary relevance of a story that in its retelling by Brunelle and Finley-Croswhite reaches nearly to the present day.

In their study of Marx Dormoy and his murder, Brunelle and Finley-Croswhite provide something for scholars and casual consumers of history alike. Fans of true crime, especially, will not be disappointed. The book follows the conventions of crime writing (sections like “The Anatomy of Murder” and “Who is [the mysterious] Mademoiselle Gérodias?” testify to this) and, for a story whose denouement is in some ways a foregone conclusion, it provides satisfactory twists and turns along the way.

Readers will be rewarded not with a sense of justice served but at least with a satisfactory sense of certainty about the crime and a greater understanding of the tangled political landscape of mid-twentieth-century France.