Ludwig van Beethoven’s First Symphony premiered on April 2, 1800, at Vienna’s Burgtheater Theater. It was the dawn of a new century, one in which advances in science, industrialization, urbanization, and novel ideas about human expression took hold. It also saw the decline of the aristocracy-based patronage system, which had sustained composers for generations.

Now, middle-class audiences flocked to public concert halls to applaud the latest music. It was in this environment that Beethoven tested the genre in which his legacy is most profoundly felt today.

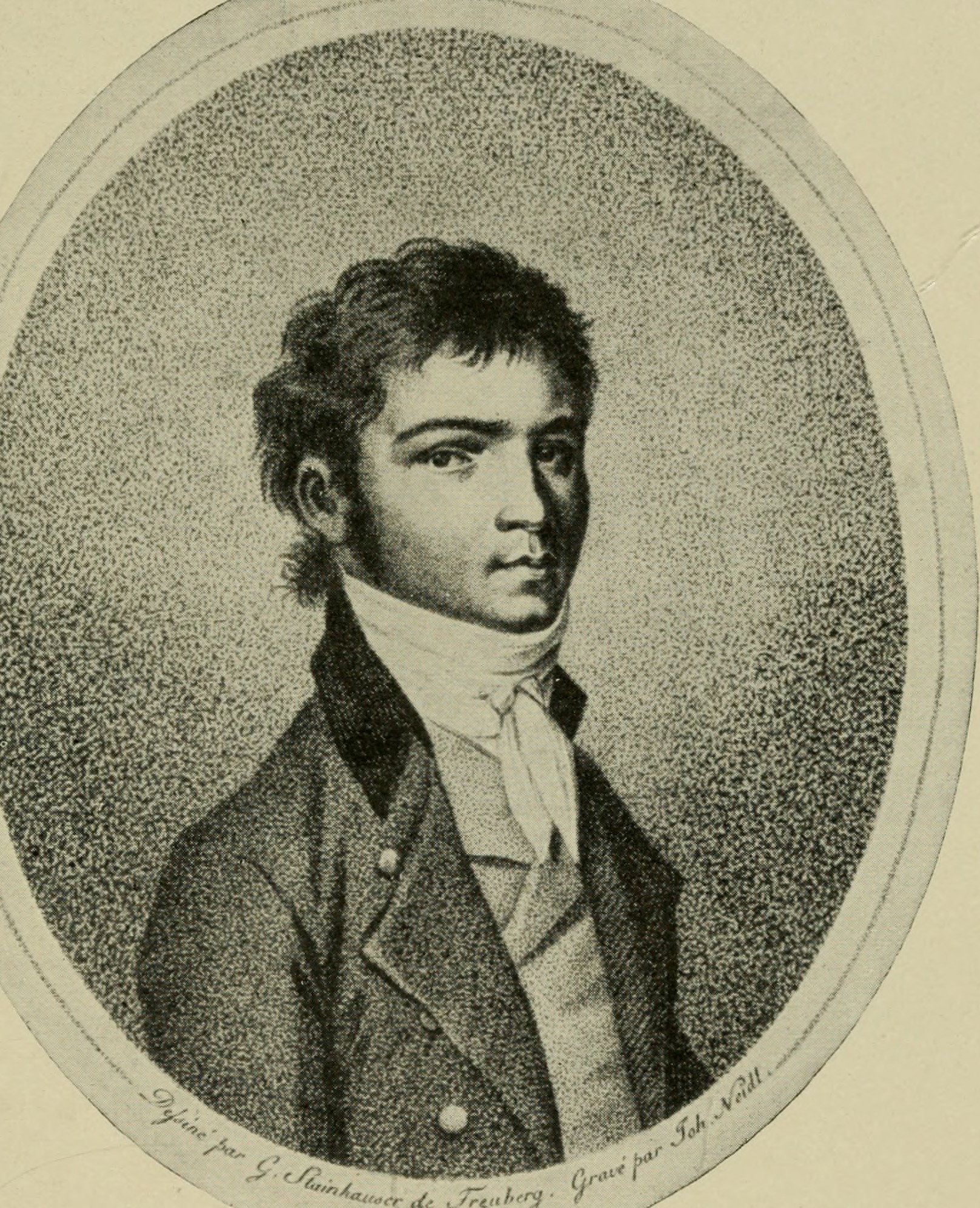

In late 1792, Beethoven left his native Bonn to seek his fortune in Vienna. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who had died the year before, reshaped expectations for the symphony, as had Joseph Haydn, an elder statesman in music.

In Vienna, Beethoven made professional connections, performed on the piano to an admiring public, and published several compositions. Among these were his four-movement piano trios (violin, cello, piano) op. 1, and the virtuosic op. 2 piano sonatas. In 1799, he started a symphony. Although he eventually shelved it, some of its ideas resurface in the First Symphony.

Beethoven turned thirty in 1800 and was the “man of the hour” thanks to his skill as a pianist and his remarkable compositions.

Distinguishing himself as a symphonist was no small proposition, however. For one thing, although the new bourgeois public demanded music, it was not easy for composers to find venues in which to showcase large-scale works, at least not initially.

For another, with Mozart’s death and Haydn deciding to devote himself to other projects, the symphony itself was on the decline. Beethoven changed all that, and by 1822 a contemporary critic recognized the symphony as “the highest genre of instrumental music.” Surely the grand occasion at the Burgtheater helped cement this new status.

The symphony was a genre Beethoven knew well. He admired Haydn and Mozart’s symphonies, and having played viola in the court orchestra in Bonn, Beethoven also knew hundreds of other symphonies, many forgotten today. The First Symphony reflects both this comprehensive knowledge and Beethoven’s burgeoning compulsion to innovate.

Following the lead of Haydn and Mozart, Beethoven launches movement 1 with a slow introduction containing various harmonic surprises. It ushers in an energetic Allegro con brio dominated by a triad-based theme, sequentially treated. The noisy bustle of its coda makes a fine contrast with the calm second movement, in sonata form, and with a serenade-like main melody. Movement 4 begins humorously, with a halting ascending scale that ultimately bursts into a witty rondo.

So where does Beethoven depart from tradition?

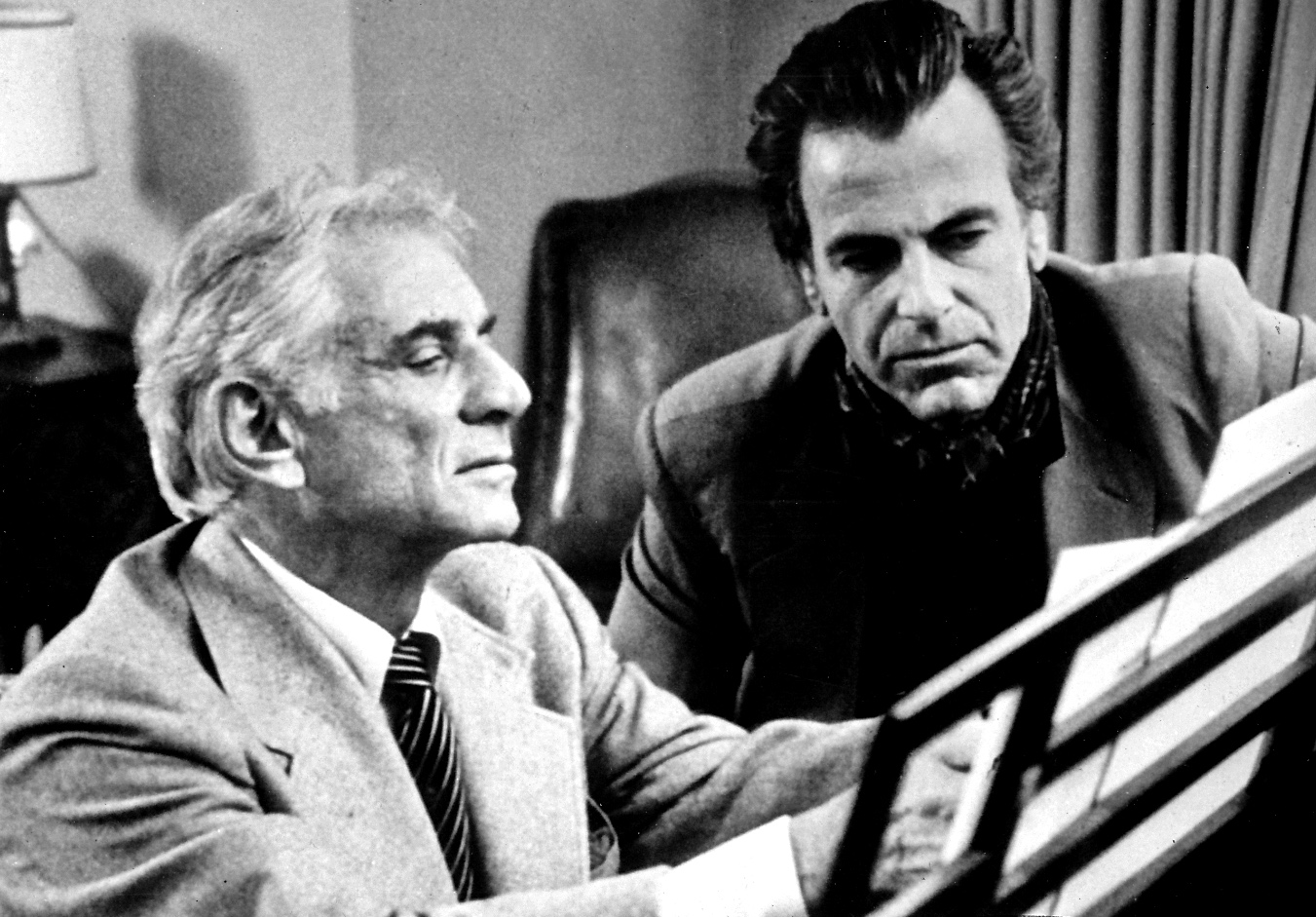

In movement 3, listeners would expect a minuet; indeed, Beethoven marks the score “menuetto.” But the tempo, much faster than that of any ordinary minuet, nudges the listener toward the future, a point the late American conductor and pianist Leonard Bernstein illustrates by playing the movement in ordinary minuet tempo, which turns out to be rather dull.

Eventually, Beethoven would call such movements “scherzo,” a term rooted in the German verb “scherzen” (to jest). Also noteworthy is the stark simplicity of the minuet’s thematic material: an ascending scale in the first section and insistently repeated notes in the trio (middle) section. In later works, Beethoven would exploit this tendency toward motivic sparseness in unprecedented ways.

Critics reacted cordially to the new work. But since that night in 1800, several have reevaluated the First Symphony.

One calls it “slender,” remarking that it “can seem almost to wilt when commentators examine it for clues to future symphonic greatness.” Others resort to words such as “competent,” suggesting that Beethoven was content merely to emulate Haydn and Mozart.

In 1862, the French composer Hector Berlioz went so far as to deem the First Symphony “admirably framed: clear, vivacious” but also “cold, and sometimes even mean,” reaching the damning—and exaggerated—conclusion, “in a word, Beethoven is not there.”

But it didn’t take long for Beethoven to both dazzle and confuse his listeners. Even though Beethoven’s Second Symphony is similar to the First in several ways, a German critic called it “a crass monster.”

Even more “monstruous” was the Third Symphony (Eroica), with its unprecedented scope. The Fifth Symphony, with its extended, development-like codas, and the Ninth, which introduces a chorus in a symphonic context, all broke new ground.

Ultimately, Beethoven’s symphonies both intimidated and inspired composers. Brahms, for example, delayed many years before attempting the genre, claiming that he constantly heard the “footsteps of a giant” behind him.

And because Beethoven died while writing a tenth—AI finished it in 2021—a legend grew up about the dangers of composing more than nine symphonies, reinforced by the fact that Gustav Mahler, Antonín Dvořák, and the U.S. composer Roger Sessions all died without completing a tenth.

The symphony is no dusty, moribund genre. Nor is it confined to Europe, with its venerable musical traditions, as a mere glance at Russia will reveal. From the far-flung Western Hemisphere, Bernstein and his compatriot Aaron Copland, both wrote large-scale symphonies, in part to prove that the United States could compete with European masters.

Composers elsewhere in the Americas have composed quantities of symphonies: M. Camargo Guarnieri and Heitor Villa-Lobos (Brazil), Juan Orrego-Salas (Chile), Paul Desenne (Venezuela), Carlos Chávez (Mexico), Roque Cordero (Panama), and many others. In 2024, Roberto of Puerto Rico completed his Seventh Symphony.

The genre has also proved versatile. John Corigliano, of the United States, chose it to mourn the loss of those who died in the AIDS epidemic, subtitling his first symphony “Of Rage and Remembrance” (1990).

One quintessentially American creation is Swing Symphony, composed in 2010 by Winton Marsalis, the celebrated trumpeter but who has received Grammy awards in both the jazz and classical categories.

Beethoven lurks in the background of all these works.

During World War II, the motif that launches the Fifth Symphony symbolized impending victory (V= dot-dot-dot-dash in Morse code).

From 1956 to 1970, the Huntley and Brinkley Report announced the evening news with the opening of the second movement of the Ninth Symphony, a gesture to which newsman Keith Olbermann alluded in his program Countdown from the early 2000s.

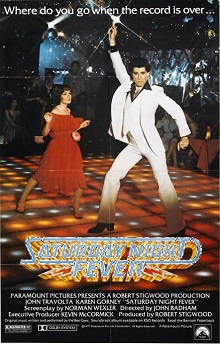

Pop culture has also taken advantage of Beethoven: one famous instance is Walter Murphy’s “A Fifth of Beethoven,” a disco arrangement of the first movement of the Fifth Symphony that served as the soundtrack to the 1977 movie Saturday Night Fever. Nor have Beethoven symphonies been exempt from politics.

One could hardly have foreseen this unusual trajectory back in April 1800, when the First Symphony, respectful of its antecedents but bursting with Beethovenian boldness, first saw the light.

![]()

Learn more:

A. Peter Brown, editor. The Symphonic Repertoire. The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992.

Carol A. Hess. “The Symphony in Latin America.” Part 1 (South America), part 2 (Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean). The Symphonic Repertoire, vol. 5, part B, The Symphony in Europe and the Americas in the 20th Century. Brian Hart, ed. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2024, pp. 665-734, pp. 735-92.

D. Kern Holoman, Evenings with the Orchestra: A Norton Companion for Concertgoers. New York: W. W. Norton, 1992.

Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies: An Artistic Vision. New York: W. W. Norton, 2015.

Alex Ross, “Toscanini, Trump, and Classical Music as a Tool of Power.” The New Yorker, 12 July 2017. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/toscanini-trump-and-classical-music-as-a-symbol-of-power<accessed 18 February 2025>.

Maynard Solomon, Beethoven. New York: Schirmer Books, 1977.

Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014.