For Americans, HIV/AIDS was a phenomenon of the 1980s. That was when the epidemic first spread across the country; that was when activists galvanized to lobby for changes in the way medical treatments were developed and approved. But as historian Thomas F. McDow describes this month, HIV/AIDS has a much longer history that goes back a century. And while AIDS was initially called "the gay cancer" in the United States, its spread around the world has much more to do with colonialism in Africa and the globalization of the economy in the 20th century.

On December 1, World AIDS Day, should we wish the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) a happy birthday?

We don’t know the exact day the virus infected its first human host, but scientists have shown that the virus has been active in humans for about a century. A biography of the disease would show a dynamic, lethal virus that worked for decades in relative obscurity before bursting on to a worldwide stage in the early 1980s and rewriting the script of human progress against disease.

The résumé of HIV is astounding. Its dominant form, HIV-1, has killed 35 million people since 1981 and it has infected roughly the same number again. Nearly 37 million people live with the disease today.

By disabling human immune systems, HIV has also allowed tuberculosis to come thundering back as a global health threat and has reduced life expectancies in many hard-hit countries.

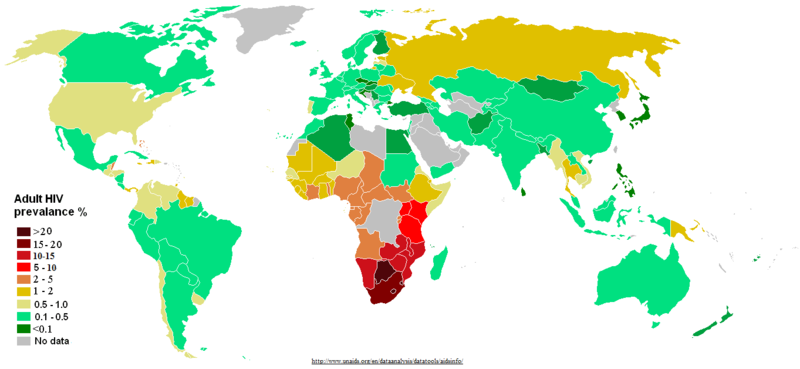

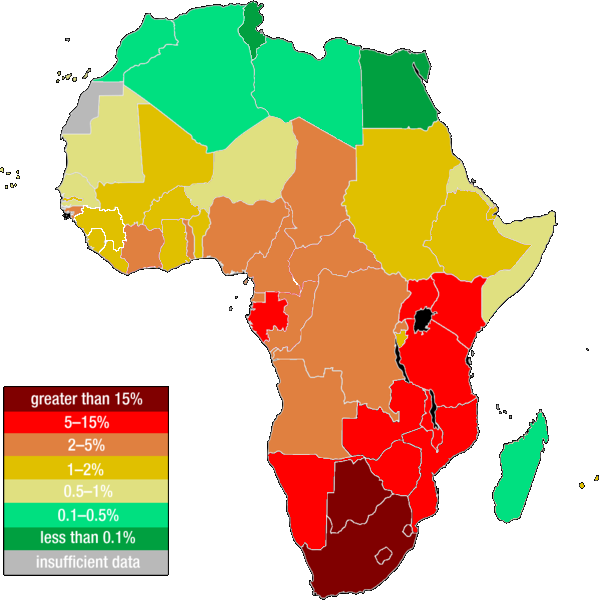

Estimated HIV/AIDS prevalence in 2011.

More positively, HIV has forced societies to shift the debate on rights and inclusion for sexual and gender minorities. Gay populations have become more visible and politically active, winning civil rights and acceptance in the wake of the disease’s devastation.

HIV has sped up the processes for drug approval in the United States and reframed the ethical framework for patient participation in research studies. The virus has also spurred scientists to create a large number of drugs in a very short time that are effective in halting the advance of the disease. Furthermore, conflicts over HIV undercut global intellectual property laws that protected drug companies and made lifesaving drugs inaccessible.

The logo for the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

The responses to the disease have also challenged global public health governance and rewired the global health apparatus. The World Health Organization began the fight against the disease in the 1980s but their efforts were ineffective. The United Nations took over in 1996, through the Joint UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

The 2015 logo for the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief in the Central Asia Region.

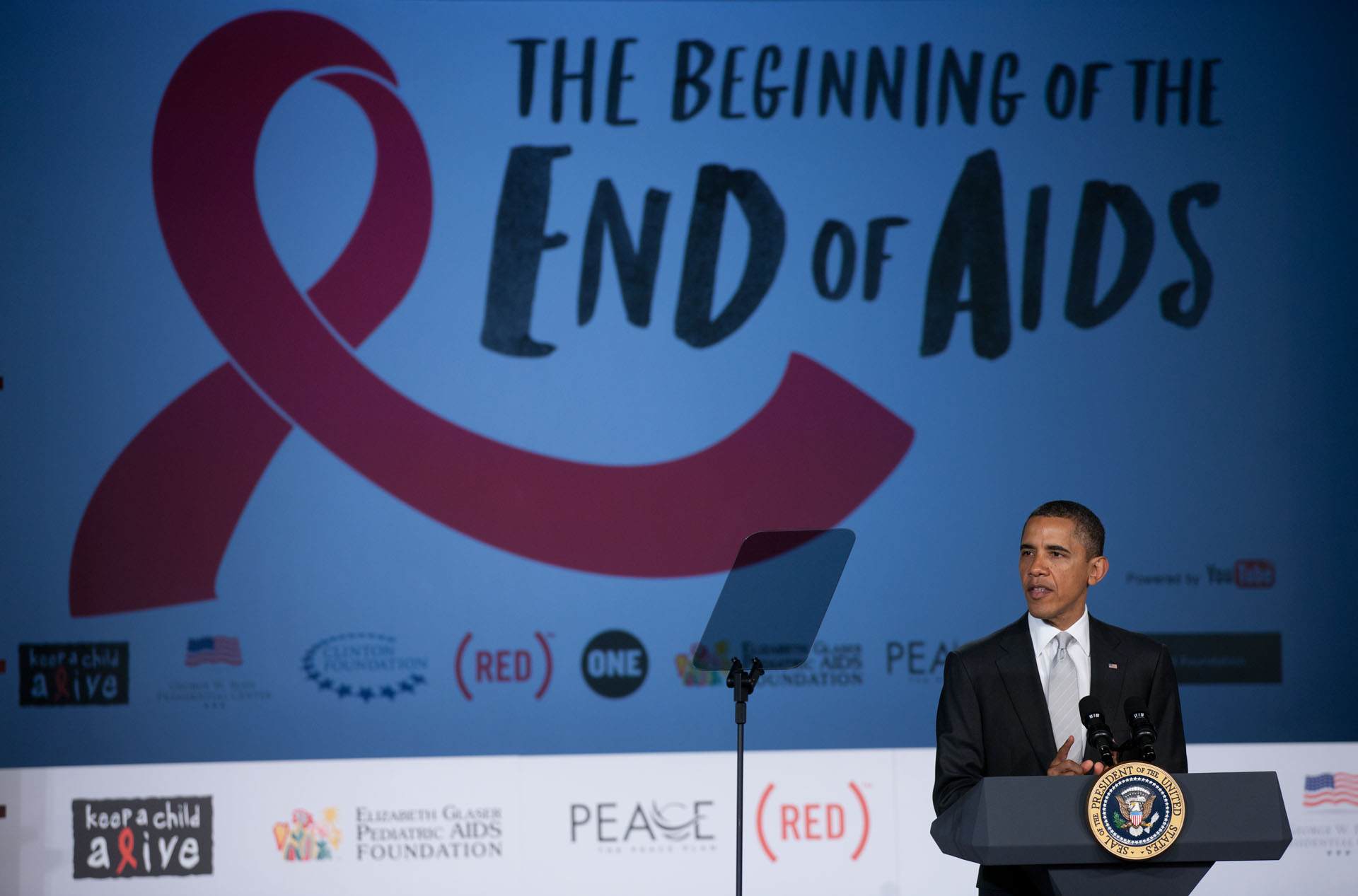

Concerns about funding and management of UNAIDS, however, led bilateral donors and private foundations to establish a public-private financing institution, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria, in 2002. The next year, the United States began what would grow to a $70 billion investment in controlling HIV over 15 years through the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund.

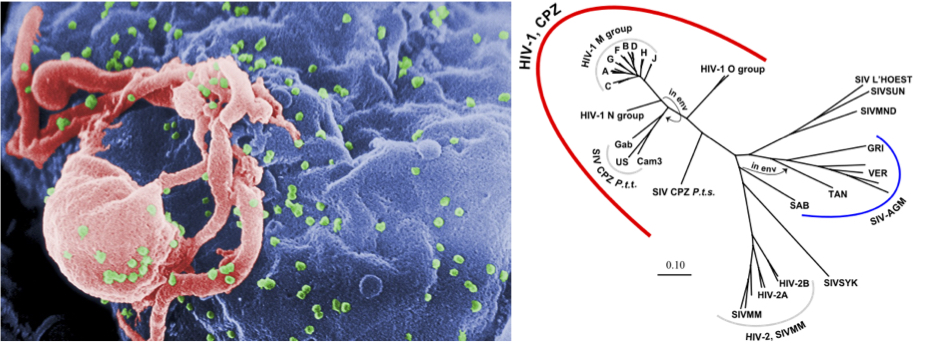

All of this happened as a result of a seemingly unlikely occurrence: a human living about one hundred years ago in Equatorial Africa became infected by a closely related virus in the blood of a chimpanzee.

HIV is derived from simian immunodeficiency virus, and we hypothesize that it crossed over to humans through blood to blood contact, probably during butchering or hunting chimpanzees. When the simian virus entered the human’s blood stream, it gradually took over cells in the immune system, hijacking CD4 cells to make new copies of the virus before killing the cells.

The insidious thing about the virus, however, is that it does its work slowly. Without treatment, HIV has a latent phase that can last between six and ten years. During that time, people harboring the virus do not know they have it, but they can spread the virus to others through sexual contact, blood-to-blood contamination, and mother to child transmission.

The story of HIV is a story of globalization. The expanding connections of the twentieth century spread the disease, yet the limitations and inequalities of global public health allowed the disease to ravage populations even after scientists discovered effective drug treatments.

A Virus Appears

In the nearly four decades since 1981, when a cluster of unusual pneumonia cases in Los Angeles introduced the world to AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), scientists have dug into its past to determine the history of the disease.

The archive of this history turned out to be two previously forgotten samples from blood plasma and a lymph node stored in a laboratory in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. By testing these two samples from 1959 and 1960, the period just before and just after the Congo became an independent nation, scientists found remnants of HIV.

A stamp commemorating the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s independence (left). A map of the Congo (right).

Because HIV has a defined mutation rate, researchers were able to compare these two samples and more recent strains of HIV to construct a family tree all the way back to a common ancestor virus. This pointed the scientists to the period when the simian virus became a human virus. But where did this happen?

They found the answer in monkey poop. A team of scientists collected the feces of chimpanzees across a wide belt of Equatorial Africa. By locating and isolating the strains of the simian virus in these samples, they pinpointed the chimpanzees with the strain of simian virus closest to the human virus on the banks of the Sangha River, a tributary to the Congo, that runs through southeastern Cameroon.

Colonial Africa: The Crucible of HIV

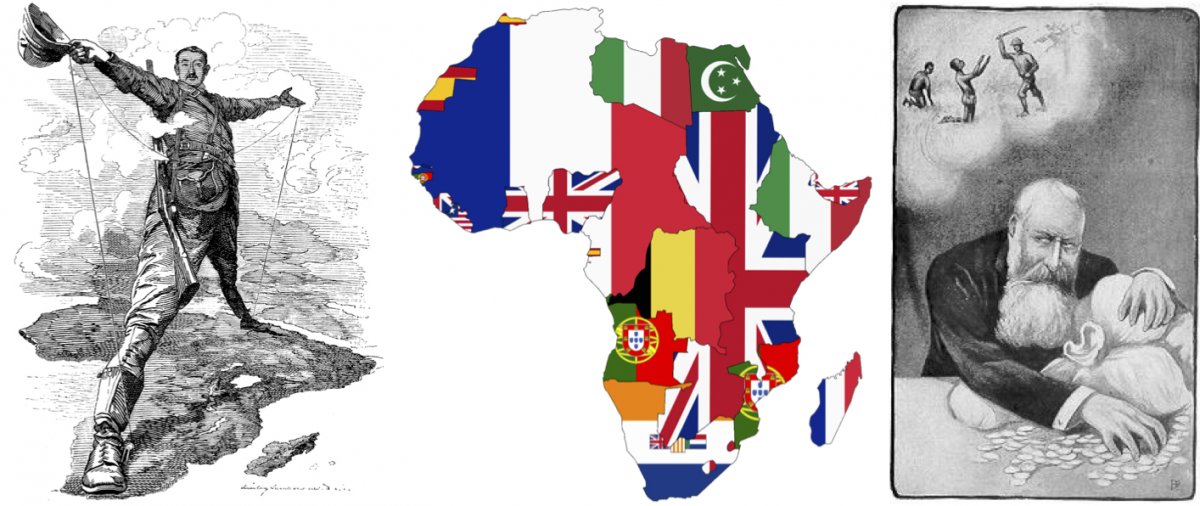

The globalization of European imperialism helped incubate and spread HIV within Africa.

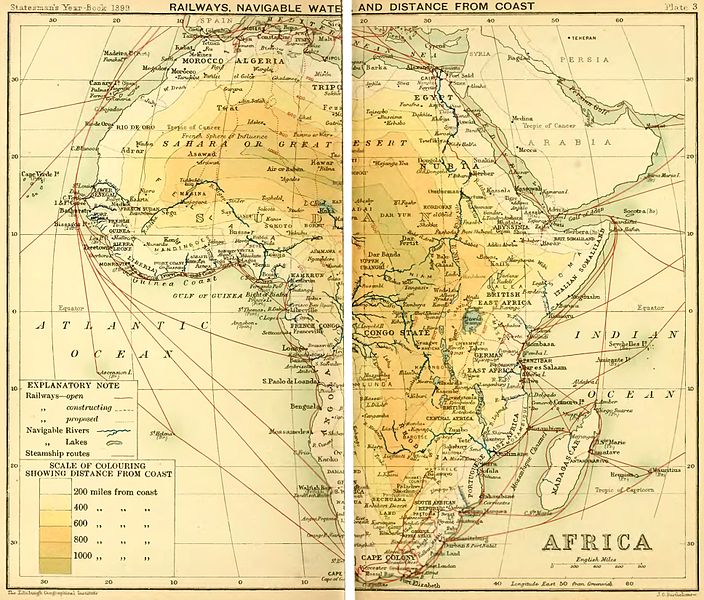

An 1899 map of Africa highlighting its railways, navigable waters, and distances from the coast.

This virus began its career in humans at a time when the forests and riverine landscapes of Equatorial Africa became increasingly connected to the global economy. While the people who lived in these forests had traded and been connected to wider regional networks for a very long time, the scope and scale of these interactions changed at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries.

European countries claimed sovereignty over much of Africa in the wake of the 1884 Berlin Conference. In Equatorial Africa, European countries broke their territories into concessions and then private companies bought the rights to control these areas and their resources.

An 1892 caricature of Cecil Rhodes, a British businessman who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, standing from “Cape to Cairo” (left). A 1939 map of Africa with flags representing the colonial claims (center). A 1905 caricature of Belgian King Leopold II with his earnings from the Congo Free State and exploited workers in the background (right).

Concessionary companies worked in the Sangha river basin, and the brutal exploitation of people to extract ivory and rubber in the broader region inspired Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness. The horrors of this exploitation led to a widespread campaign against the Belgian King Leopold II’s murderous reign in the Congo.

European colonialism built an infrastructure that helped link previously unconnected regions. Steamboats plied the rivers, speeding the transport of goods and people. New towns on the river grew into trading centers and colonial outposts.

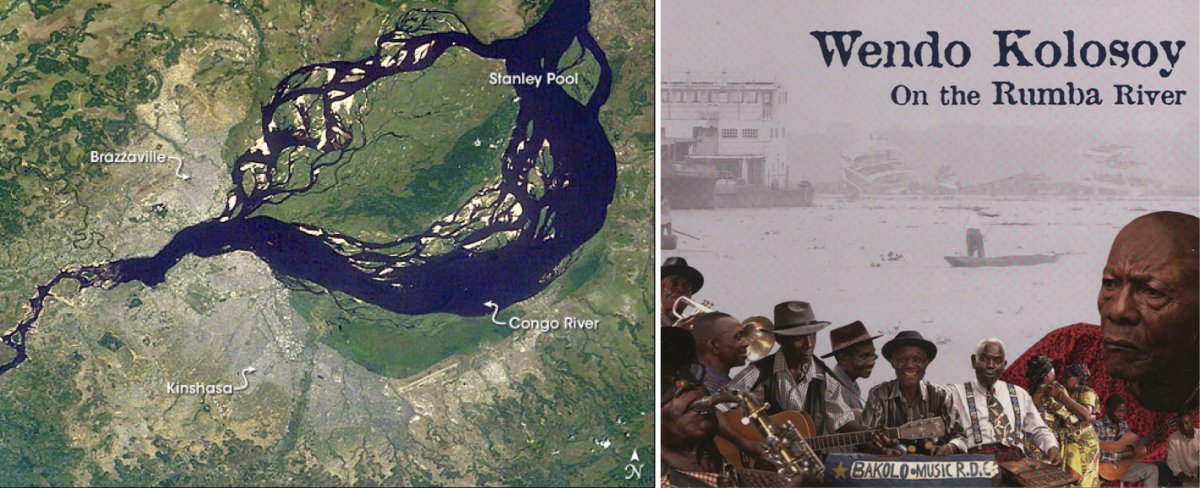

Two towns on opposite sides of the Congo River, Leopoldville (now Kinshasa) and Brazzaville, attracted Africans from across the equatorial belt.

A satellite image of Brazzaville, Kinshasa, and the Malebo Pool (formerly Stanley Pool) of the Congo River (left). Papa Wendo Kolosoy’s 2004 album “On the Rumba River” (right).

In the 1940s and 1950s, the creative energies of these towns produced the lively sounds of rumba, music inspired in part by Latin American sound and driven by the distinctive Congolese guitar playing. But the same venues and impulses that attracted the youth to hear people like Papa Wendo Kolosoy croon “Marie Louise” created conditions for the spread of the virus through heterosexual intercourse.

While it is impossible to know how many people were infected with HIV in this period, rates of other sexually transmitted diseases like Hepatitis B suggest that HIV could have spread widely. And it was in 1959, the last year of Belgian rule in the Congo, that a doctor in Leopoldville took a fateful tissue sample from a patient.

Decades later this obscure sample from colonial Africa would help unlock the origins of HIV.

HIV-1 (in green) under a scanning electron micrograph (left). A phylogenetic tree of the HIV and simian virus (right).

From Africa to the World

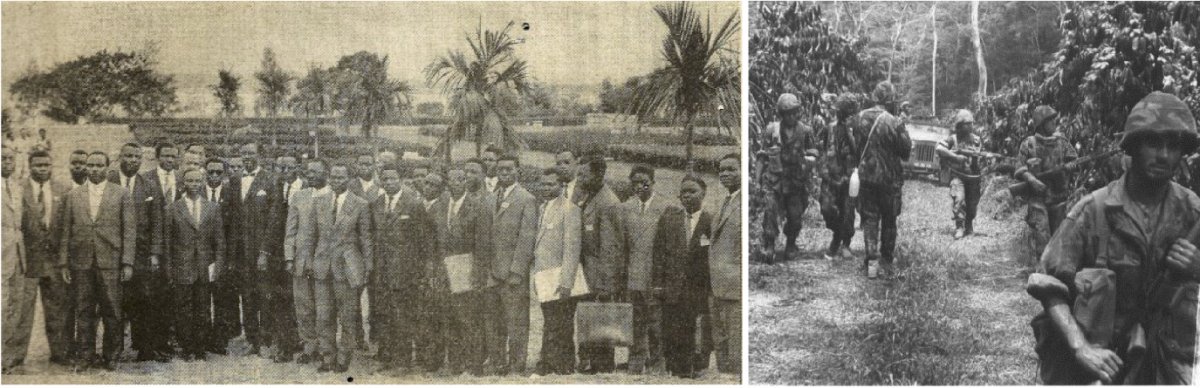

If colonial Africa incubated and magnified the reach of HIV-1, however, it was the end of European colonization and the tensions of the Cold War that created the conditions for the global spread of the disease.

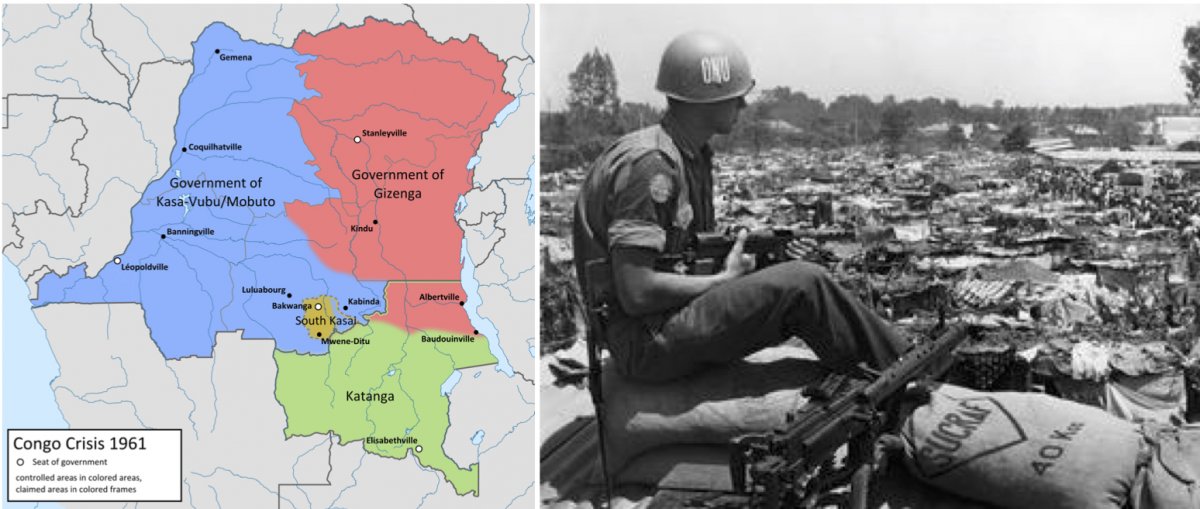

The 1960s have been hailed as the African Decade because so many African countries emerged from colonialism. But these emerging nations also became battlefields in the Cold War struggles between the United States and the Soviet Union. The Congo provides the most striking example of this in the 1960s.

Patrice Lumumba (left center) immediately after being sworn in as the first Prime Minister of the newly independent Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1960 (left). Portuguese soldiers in Angola during the War of Liberation between Portugal and Angola from 1961 to 1974 (right).

The Belgians rushed the process of Congolese independence in 1960, but in the days following the formal handover of power to Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, the country’s most resource-rich province, Katanga, seceded. Katanga’s mines produced vast amounts of copper as well as the uranium that produced the fuel for the American bomb that decimated Hiroshima.

The secession sparked a five-year conflict during which Lumumba was assassinated and overthrown, the UN Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld’s airplane was shot down, and Belgian and UN troops occupied parts of the country. Joseph Mobutu, an army officer, emerged as the head of state in the Congo and remained a staunch Cold War ally of the United States.

A 1961 map of the factions in the Congo (left). Swedish UN soldier in the Congo in the 1960s (right).

A side effect of Congo’s rushed independence and the resultant crisis was a dearth of people with professional training and experience. In response, the United Nations Education, Science, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Congolese government recruited teachers and doctors to come work in the Congo. After Belgians, Haitians made up the largest number of these expatriate professionals.

A Cuban tank in Angola in 1976.

There were an estimated 4,500 Haitians in the Congo in the 1960s, and more came in the 1970s. These Haitian professionals sought respite from their own Cold War dictator. While in Congo, however, some contracted HIV and subsequently returned home with the deadly, unknown virus. The earliest cases of HIV in the United States are connected to Haiti, and the Haitian-Congo link seems to have helped the disease cross the Atlantic.

Angola’s liberation struggle and civil war in the 1970s and 1980s also connected the Cold War and the global spread of HIV.

Fidel Castro committed Cuba’s Communist government to support the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) in their struggles to control Angola, both up to Angolan independence in 1975 and during the civil war that followed. Tens of thousands of Cuban soldiers, aid workers, and doctors were sent to Angola between the 1960s and the early 1990s.

Cuban and Angolan forces eventually defeated the South African Defense Force in Angola in 1988, which set into motion the independence of Namibia, the freeing of Nelson Mandela, and the end of apartheid.

A map showing Cold War alliances in 1980.

For many Cubans who served, however, the momentous outcome of their African service was the virus they contracted.

We now understand this pre-history of AIDS. Looking back, doctors can see that a small number of unexplained medical cases in the west from the 1960s and 1970s were early cases of AIDS. Scientists’ more recent efforts to identify the genetic subtypes of HIV and put them into family trees reveals the disease’s evolution and movement.

By the 1970s, a powerful wave driven by decolonization and Cold War rivalries was cresting. In the early 1980s, this wave crashed around the globe.

AIDS Emerges among Gay Men in the U.S.

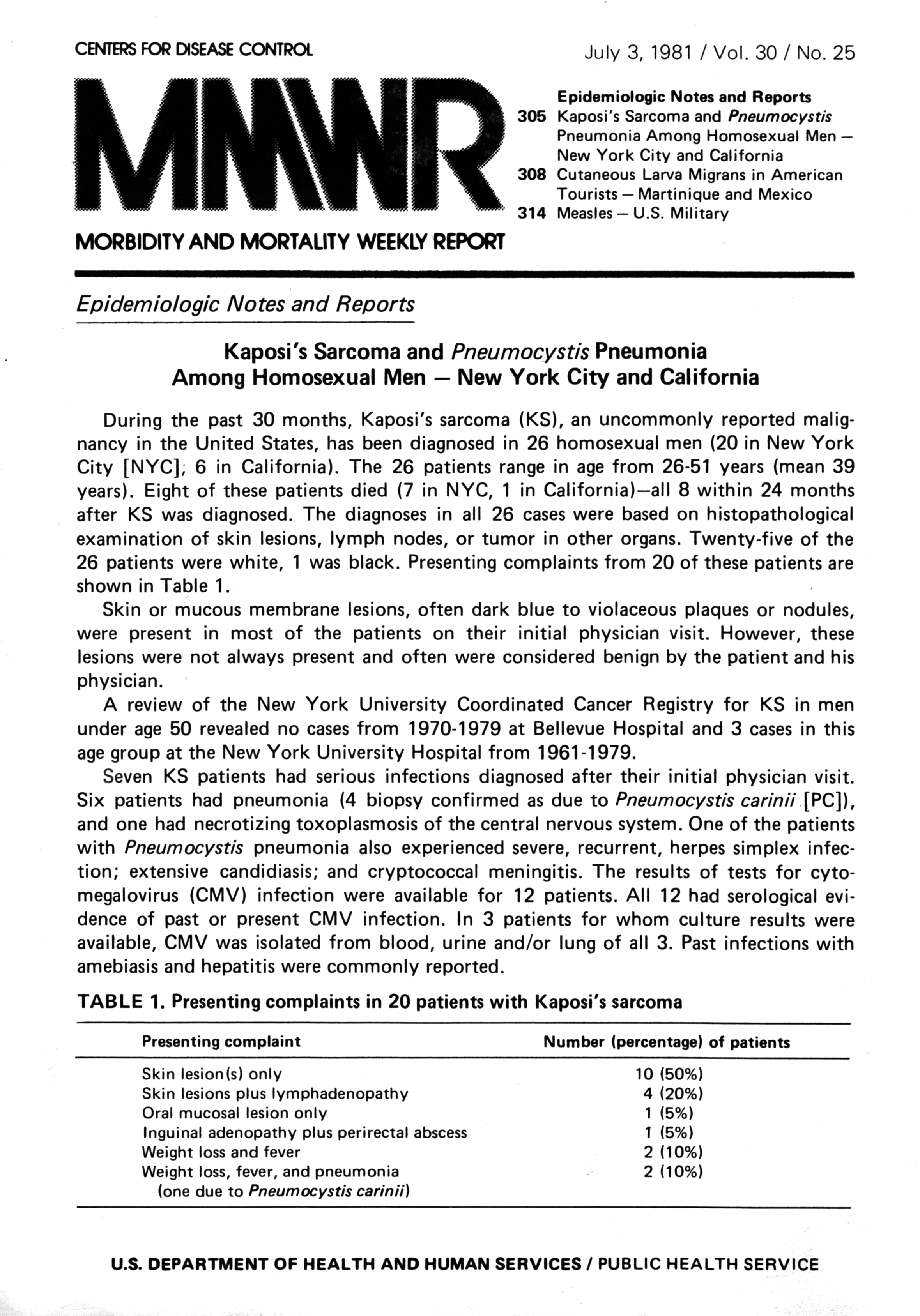

A curious cluster of unusual pneumonia cases in Los Angeles in June 1981 resulted in the first public health report of a pattern of infections among gay men.

The Centers for Disease Control’s Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report of June 5 set off alarm bells for a small number of physicians who had seen similar strange cases of failing immune systems that left the body susceptible to infections that healthy people repel every day. They saw young men who had diseases like pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and Kaposi’s sarcoma, infections that they would never have seen in otherwise healthy people.

The medical mystery was a lived misery. Healthy young people suffered terribly from rashes, diarrhea, and infections. Thrush in their mouths and throats made it hard to swallow. Some lost their vision and others developed dementia. With the progression of the disease, the infected withered and hollowed, becoming unrecognizable. The stigma of being gay in the United States discouraged some from seeking treatment when they became ill, and those who did faced discrimination in many forms, including refusal of care from hospitals.

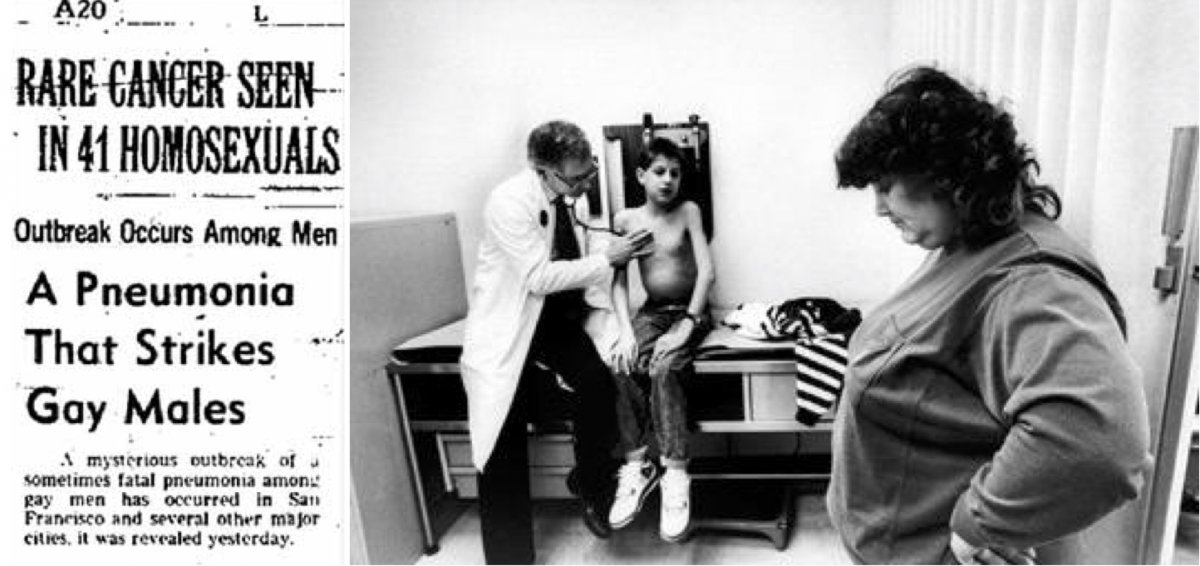

The disease was initially called a “gay cancer” and then Gay-Related Immune Deficiency (GRID) in the United States, but it dawned on physicians in Africa that their heterosexual patients had the same disease. The Centers for Disease Control gave the new disease a more neutral name, Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS), in September 1982.

A newspaper clipping from 1981 (left). Ryan White, a boy with hemophilia, became a poster child for HIV/AIDS in the U.S. after his school refused to readmit him after his diagnosis of AIDS in 1984 (right).

Naming the disease was easier than characterizing it, and the early diagnosis was based on having a number of AIDS-defining illnesses. With no known cause and no known cure, these were desperate times.

Hemophiliacs contracted AIDS from donated blood, and tainted blood supplies spread fear in society. People believed they could contract AIDS from a sneeze or a toilet seat, and the panic further marginalized those who had the disease.

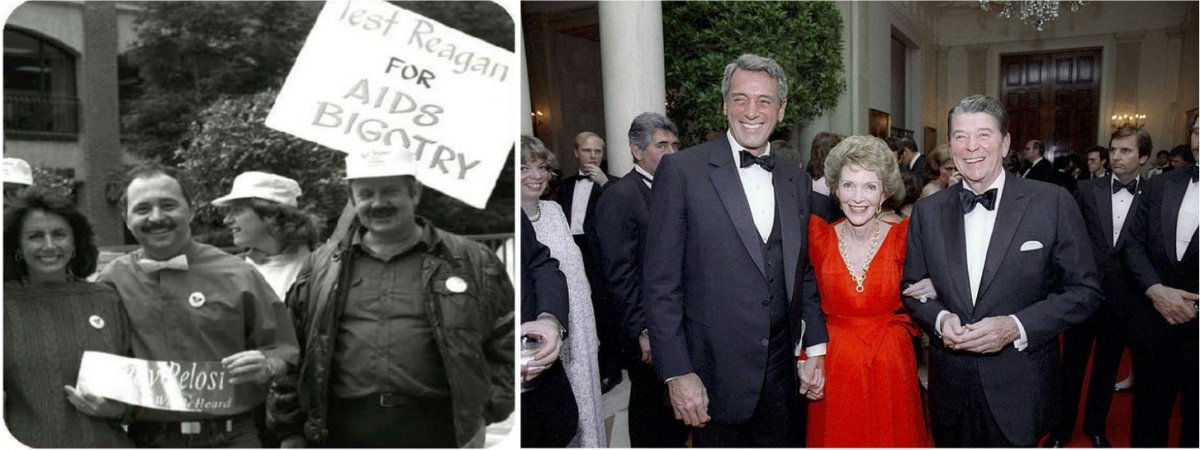

Congresswoman Nancy Pelosi at the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987 (left). Despite being close friends with Rock Hudson, President Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan made no public statements regarding the actor’s death from AIDS in 1985 (right).

Stigma and fear shaped official responses to AIDS in western countries where gay men were most affected. Conservative governments under Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher avoided the subject of AIDS for as long as possible and provided grossly inadequate funding for research and outreach. The virus that caused the disease was not definitively identified until 1984, and the first test for it was not available until 1985.

But there was still no cure. AIDS was a death sentence.

Neoliberal Globalization, Inequality, and HIV

The growing impact of AIDS coincided in the West with reductions in public sector institutions and their replacement with private ones. These so-called neoliberal governance strategies set conditions for foreign aid and shaped guidelines for liberalizing economies in the developing world. They also created the conditions for economic globalization.

In response, governments in many parts of the world scaled back their public sectors, limited funding for education and health care and required people to pay user fees to access them. These forces gave rise to a proliferation of nongovernmental organizations in many places. In these ways, the forces of globalization that were supposed to liberalize the economies around the world fanned the spread of HIV and hampered its control.

A 1990 ACT UP demonstration at the National Institutes of Health demanding more research on AIDS (top left). ACT UP demonstrators at the first Fresno Lesbian-Gay Pride Parade in 1991 (top right). ACT UP and Occupy Wall Street protestors in 2012 demanding a tax on Wall Street to fund global AIDS treatment, prevention, and care (bottom left). An ACT UP protester at the ACT UP 30th Anniversary Gathering Rally in 2017 (bottom right).

In the United States, gay men and their allies founded protest groups and non-governmental organizations to try to address the disease. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) used in-your-face tactics to shame officials and researchers. They occupied the New York Stock Exchange and threw human ashes on the White House lawn. The Gay Men’s Health Crisis in New York strove to take care of people living with AIDS. These organizations did what elected representatives and the medical profession were not doing adequately: sticking up for and looking out for those at risk for contracting HIV and those who had AIDS.

The AIDS crisis of the 1980s was not just an American and Western European problem, however. Sub-Saharan Africa, we now know, was the birthplace of the disease and has been the region most devastated by it. The virus had spread silently to eastern Africa in the 1970s and eventually went south.

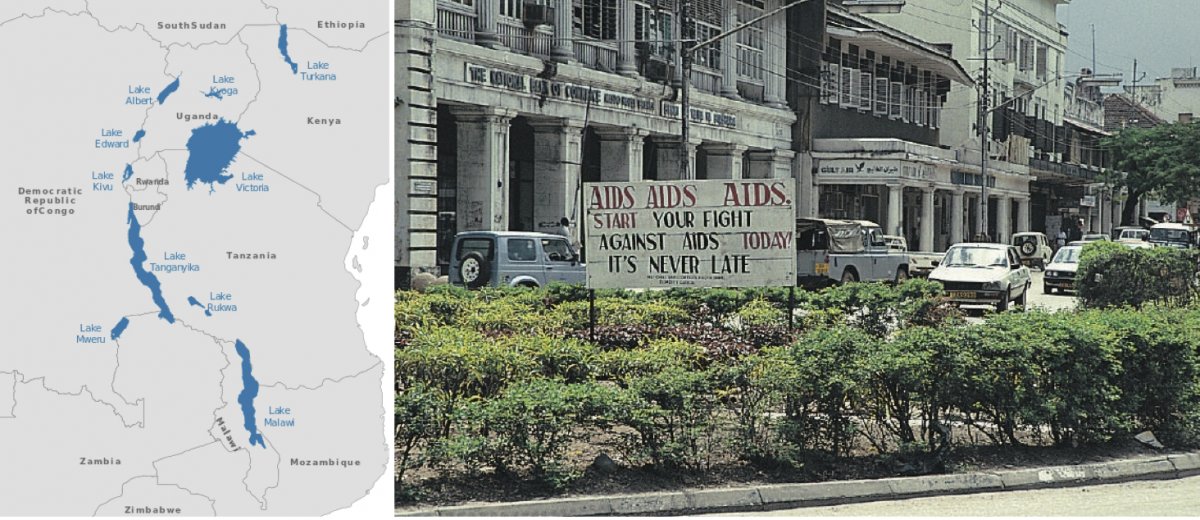

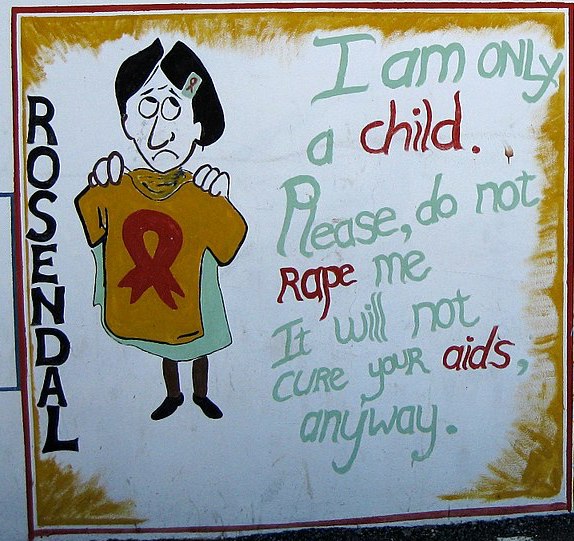

The Great Lakes region of Africa (left). A 2005 sign from Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania promoting AIDS awareness (right).

If the early North American epidemic was predominantly among gay men, the African outbreak was overwhelmingly heterosexual. While the disease had traveled down the Congo River to Leopoldville and Brazzaville, the highest rates of infection in the 1980s were in the Great Lakes region, with rapidly growing rates of infection in Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda.

Trade and transport networks within the region also spread the disease to Kenya and Tanzania, and by the end of the decade the disease had pooled at the bottom of the continent, with South Africa’s prevalence rates rising while Lesotho and Swaziland’s number of AIDS cases ballooned. In 1989, 1.2% of Swaziland’s adult population were HIV positive. A decade later, 20.6% of adults had the virus.

A 2011 map of estimated HIV infection rates in Africa.

Structural adjustment programs and conditional aid from the West required economic concessions and rollbacks of government services. Thus in Africa, as in the United States, non-governmental organizations like Uganda’s The AIDS Support Organization (TASO) tried to fill the gaps between families and shrinking health care systems.

As a consequence, there were no drugs for treatment in Africa, and with a six- to ten-year incubation period, the disease scythed the middle-aged populations. After families devoted time and resources to nurse those affected and to ease their path to death, the orphans and grandparents had to reconstitute families and restructure society.

AIDS Science and the Global Health System

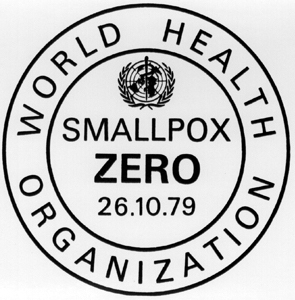

AIDS emerged on the global stage at a moment of great confidence in the World Health Organization and the promise of global health. When doctors, scientists, and public health officials described the disease that came to be known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in 1981, they had just eliminated smallpox in 1979. The end of smallpox remains one of the greatest successes in the history of the human battle with infectious disease.

The devastation and mystery of AIDS undercut decades of global public health success, however, and derailed a push for worldwide primary care. AIDS challenged both the global health system and scientific understandings of disease.

Molecular biologists and virologists raced to figure out a disease that defied the central dogma of cellular biology: that DNA encodes RNA and RNA encodes the proteins. HIV, a retrovirus, upended this scientific consensus.

Retroviruses are an unusual class of viruses that Howard Temin identified in the 1960s. His findings, however, were initially ridiculed, and only took hold in the early 1970s. Thus the study of retroviruses was still in its infancy when AIDS began to dominate headlines. Robert Gallo discovered the first human retroviruses in 1980, and his lab in the United States and Luc Montagnier’s lab in France first identified HIV as a retrovirus in 1984.

Pharmacologists and immunologists had to figure out how to stop a retrovirus. The first partially effective pharmaceutical answer to HIV arrived in 1987. Azidothymidine (AZT) slowed the effects of HIV but it was extremely expensive and available only in western countries. Those who could afford the doses found out that AZT’s effectiveness declined over time as the virus developed resistance.

The answer to treating HIV lay in combination therapies. Scientists created many new drugs in a surprisingly short amount of time. By the mid-1990s, patients who received “cocktails” of three antiretroviral drugs saw their viral loads shrink and their immune systems return. Patients who had been on death’s door returned to life in a matter of weeks.

Combination therapies could save millions of lives, but they were too expensive for most patients to afford. Pharmaceutical companies held the patents for these drugs and new global regulations allowed them, not public sector organizations, to set the prices.

A protester at the 30th Anniversary Gathering Rally NYC AIDS Memorial in 2017.

Member states of the World Trade Organization approved the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) in 1994 to codify a global standard for protecting intellectual property rights. These rights included patent protection for pharmaceutical companies.

The most prominent conflict between public health and intellectual property took place in South Africa. The inequality of apartheid had helped HIV gain a firm foothold in the country in the early 1990s, and by the end of the decade more than 20% of South Africans were infected. South Africa held its first fully democratic, multiracial elections in 1994 and had one of the continent’s strongest economies. But with average annual incomes at $2,600, most HIV-positive people could never afford the yearly cost of $12,000 for antiretroviral drugs.

The government of South Africa changed its laws in 1997 to allow it to seek better drug pricing. This set up a showdown with the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), who threatened to sue South Africa over TRIPS violations of intellectual property. A globalizing economy had spread HIV, and rules to protect the global economic system stood in the way of life-saving drugs for millions of South Africans.

While many South Africans had been dissatisfied with their government’s approach to HIV, even its harshest critics, like the Treatment Action Campaign, lined up behind the South African government. The optics of the lobbying arm of a multi-billion-dollar industry suing the country with the largest population of HIV-positive people reflected poorly on PhRMA. They dropped their suit and negotiated a way for people in the global south to obtain antiretrovirals.

Private foundations became part of the solution too. The Clinton Foundation helped broker drug manufacturing deals and offset drug costs. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation was an early, prominent donor to the Global Fund.

The Present and Future of HIV

Where global efforts fell short in stemming the virus early on, the pharmaceutical advancements and global agenda in the past decade, by taking on a more systematic approach, have made enormous advancements in treatment.

Combination therapies can be cheaply produced in a single pill, and a two-drug combination of emtricitabine and tenofovir (marketed as Truvada) was approved in 2012 as pre-exposure prophylaxis. People at high risk of HIV infection can take it daily to protect themselves from the disease.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu getting an HIV test as part of his foundation’s mobile test unit (left). A midwife in Uganda drawing a patient’s blood using a machine provided by USAID in 2012 (right).

Patients who adhere to their antiretroviral treatments can reduce their viral load of HIV to undetectable levels. With this is a growing consensus that undetectable levels mean the virus is not transmissible. This makes HIV a chronic condition to be managed for those with access to antiretrovirals.

These advancements parallel a bold goal in global HIV prevention and treatment. In 2013, UNAIDS and its partners made a plan for 2020. By then they want 90% of all people living with HIV to know their status; for 90% of those diagnosed with HIV to receive antiretroviral therapy; and for 90% of those on treatment to achieve viral suppression.

For some countries, this 90-90-90 goal is attainable. In the central African nation of Malawi, 90% of people living with HIV are diagnosed, 79% of those are on antiretrovirals, and 87% of them are virally suppressed.

The key to these successes has been a shift in the practice and funding of global health. UNAIDS, PEPFAR, and the Global Fund have realized that without robust health systems in place, HIV prevention and treatment will stall. Thus, while the WHO’s old goal of primary health care for all fell to the wayside with the advent of AIDS, the new model of treatment and prevention recognizes the importance of healthcare infrastructure. Massive investments in drug provision and health systems aim to halt new infections worldwide.

In eastern Europe and central Asia, however, the numbers of new infections and AIDS-related deaths are still on the rise. Russia reported in 2017 that 81% of people living with HIV in the federation knew their status, 45% of those were on antiretrovirals, and 75% of those in treatment were virally suppressed. For the 19% of those who are undiagnosed, and the 55% of those diagnosed but untreated, the possibility of spreading the disease remains high. HIV/AIDS rates in China have surged in recent years, increasing by 14% with 40,000 new cases in the second quarter of 2018.

Treatment Action Campaign activists during a 2003 march on South Africa’s parliament (left). A 2006 outreach session about HIV/AIDS in Angola (right).

So when we look back at a century of HIV, we see a virus that has ridden the wave of globalization, spreading with colonial structures and using the disruptions of decolonization and the Cold War to jump the Atlantic. Neoliberal globalization at the end of the twentieth century created a world open for investors but those same conditions failed to check the virus.

As we look ahead past this century of HIV, it is hard to know which global forces will most shape the virus’s evolution. The current successes in treatment and prevention hinge on tremendous financial contributions from a few countries. As populism sweeps the globe, will these countries remain willing to shoulder the cost of arresting HIV?

In 2017, when a clinical officer in rural Malawi contemplated the possible loss of PEPFAR funding, he could anticipate only one outcome. “Many people will die,” he said, and repeated, “Many people will die.”

For now, however, we can reflect on this World AIDS Day that there are more people living with HIV than have died from the disease, and the number of those living positively goes up every day.

Read more from Origins on disease and human health: The 1918 Flu Pandemic; Top Ten Origins: Flu; America's Long-Suffering Mental Health System; Influenza Pandemics Now, Then, and Again; Food and Chernobyl; Fluoride ; Vaccines; Top Ten Origins: Vaccination.

Johanna Tayloe Crane, Scrambling for Africa: AIDS, Expertise, and the Rise of American Global Health Science (Cornell University Press, 2013).

Helen Epstein, The Invisible Cure: Why We Are Losing the Fight Against Aids in Africa (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2007).

David French, How to Survive a Plague: The Story of How Activists and Scientists Tamed AIDS (Vintage, 2017).

John Iliffe, The African AIDS Epidemic: A History (Ohio University Press, 2006).

Randall Packard, A History of Global Health: Interventions into the Lives of Other Peoples (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2016).

Jacque Pepin, Origin of AIDS (Cambridge University Press, 2011).

David Quammen, The Chimp and the River: How AIDS Emerged from an African Forest (Norton, 2015).

Randy Shilts, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic (St. Martin's Griffin, 1987).

Craig Timberg and Daniel Halperin, Tinderbox: How the West Sparked the AIDS Epidemic and How the World Can Finally Overcome It (Penguin, 2012).

Abraham Verghese, My Own Country: A Doctor's Story (Simon & Schuster, 1994).