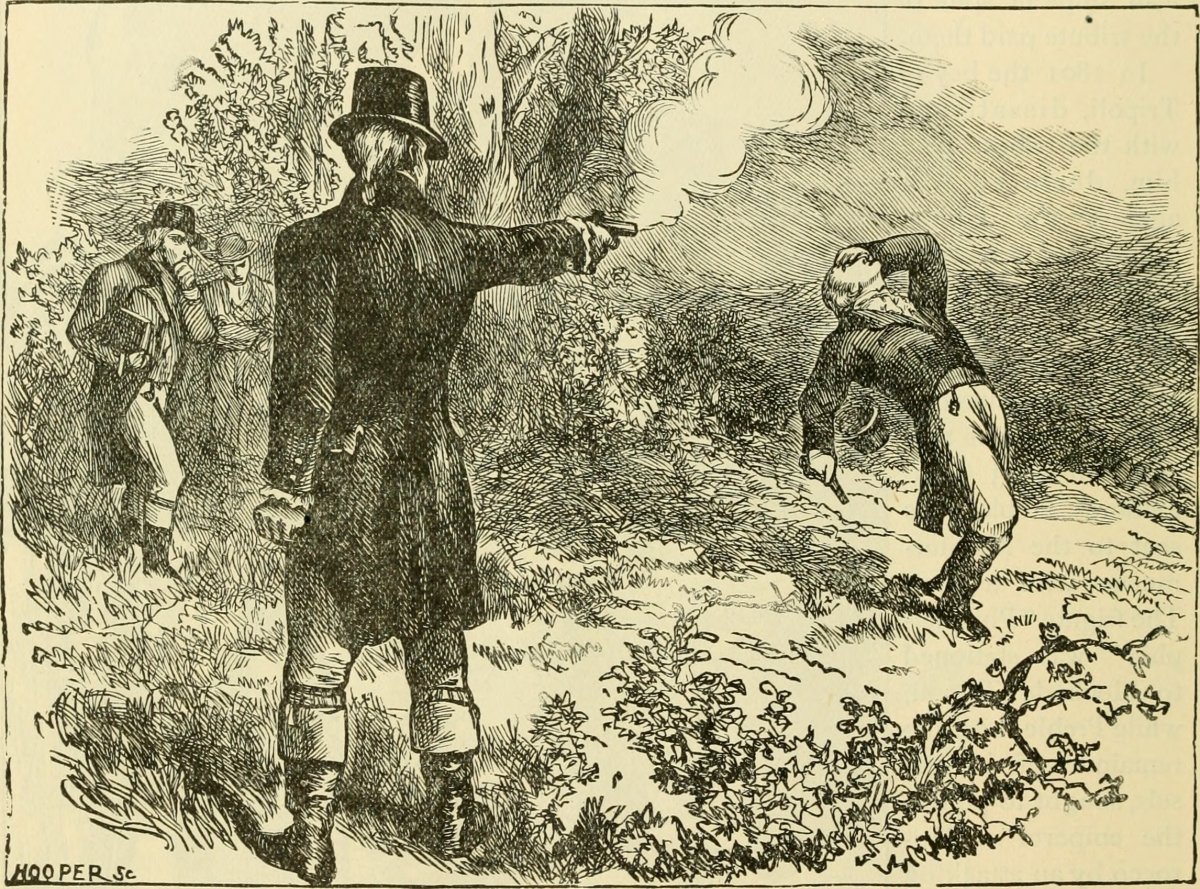

Illustration of the duel between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr (1887).

On July 11, 1804, former Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton and Vice President Aaron Burr faced off in the most infamous duel in American history. Burr fatally wounded Hamilton, who died the next day. Hamilton’s premature death transformed him from one of the last stalwarts of the fading Federalist Party to an American martyr, the namesake of towns across the country, and the face of the ten-dollar bill.

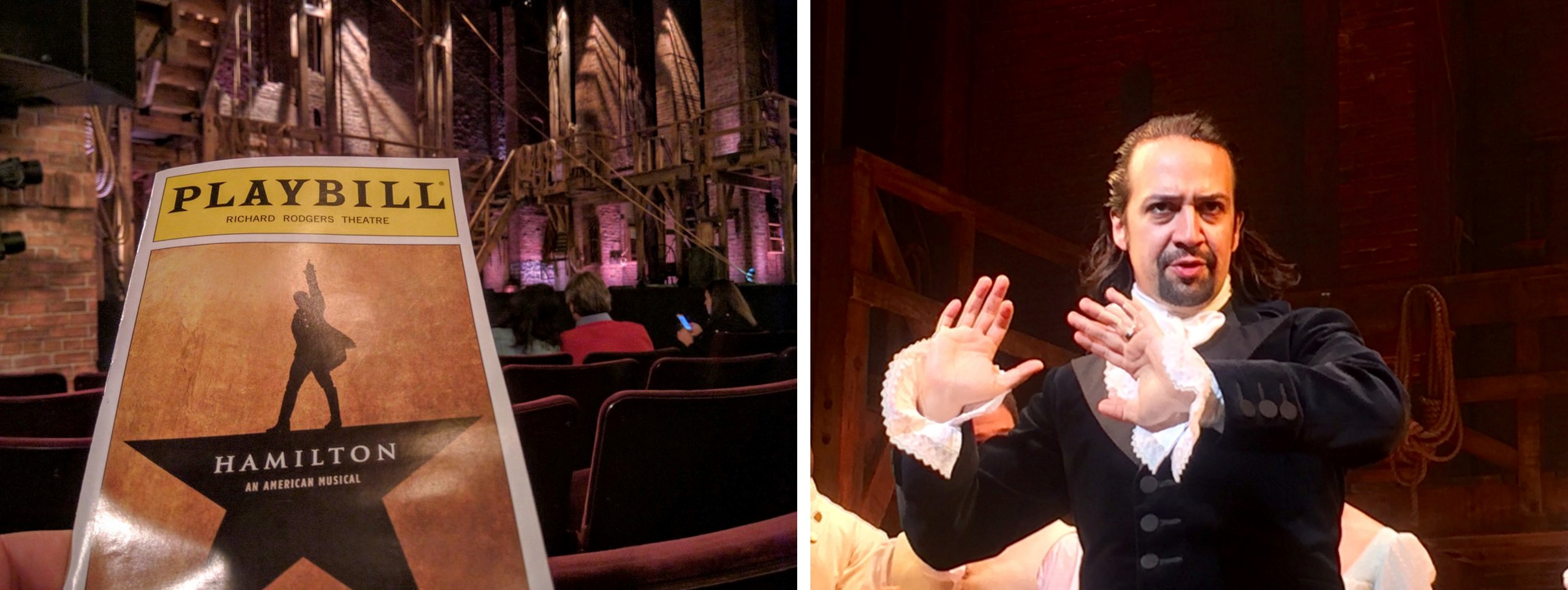

Lin Manuel Miranda (right) wrote 2015's Broadway sensation, Hamilton (left), and also starred as the Tony Award winning cast's titular character.

Two centuries later, with the success of Lin Manuel Miranda’s musical Hamilton, he has also become a pop culture icon. Meanwhile, as the character of Aaron Burr puts it in Hamilton: “He may have been the first one to die / But I’m the one who paid for it.” The duel effectively ended Burr’s public career, precipitating a slide into persona non grata obscurity and treason.

The duel culminated a simmering conflict between the two men rooted in the election of 1800. Hamilton had helped his political enemy, Thomas Jefferson, defeat Burr in that election. (Burr ran as Jefferson's vice-president, but both men ended up with the same number of votes in the Electoral College, meaning the House of Representatives decided the election—a constitutional oddity that the 12th Amendment soon rectified.) Hamilton’s well-known animosity toward Jefferson made his campaign against Burr all the more maddening.

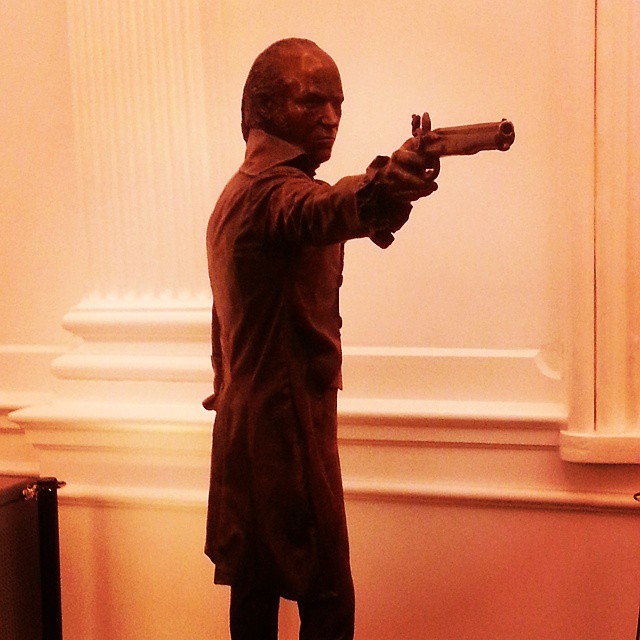

A statue of Aaron Burr on display at the 2019 Hamilton Exhibition in Chicago.

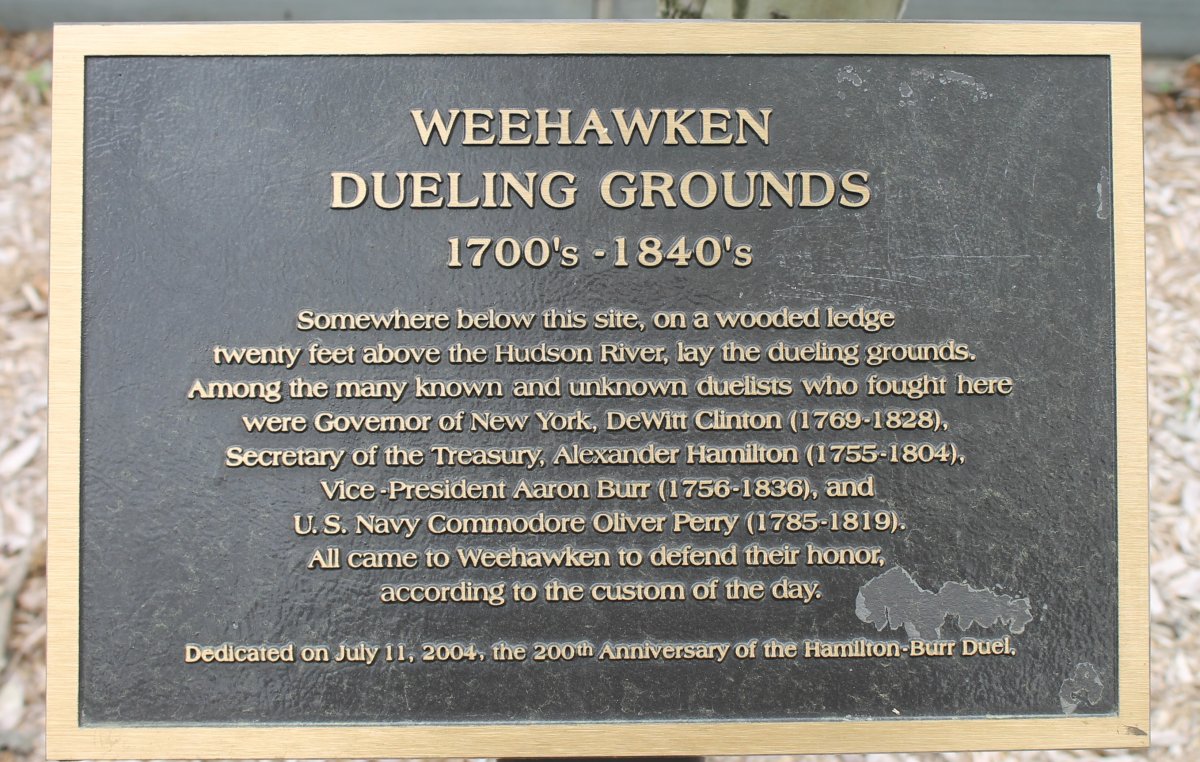

In 1804, when Burr began a campaign for governor of New York, Hamilton again waged political war. Burr took the political challenge as an affront to his personal honor. As the candidate representing his faction in the election, his loss was also seen as a humiliation to the party as a whole. Winning a duel not only won back honor after an electoral defeat, but also dishonored the duel’s loser, and by proxy, their faction.1

In the heat of that campaign, it was asserted that Hamilton claimed Burr was “a dangerous man” unfit for the trust of political office.2 Reeling from the sting of defeat and the public dishonor that accompanied it, Burr wanted to dishonor Hamilton in return.

Unwilling to put the personal affront behind him, Burr insisted on the duel.3

Accounts of the duel are, by design, shaky. Since dueling was illegal, witnesses turned their backs to the duel to give them plausible deniability. What is clear, though, is that Hamilton missed while Burr hit Hamilton in the stomach. Hamilton died the following day. Burr was charged with murder but never faced trial.

A plaque designating the Weehawken, NJ dueling grounds where the Hamilton-Burr duel took place.

Burr appeared to relish his role in Hamilton’s death, but the duel discredited him with the public—a fate that contributed to his involvement in a conspiracy to take western lands and establish a separate government. He was tried for treason in 1807 but was acquitted.

Shocking as Hamilton’s death might have been, duels were common in early American history. They were so frequent, in fact, that at the time of the Hamilton-Burr duel many leading figures, including future president Andrew Jackson, fought a duel to preserve their honor. That code of honor allowed many steps to resolve a dispute, each with their own set of cultural norms. If all those failed, a duel would settle the conflict once and for all.

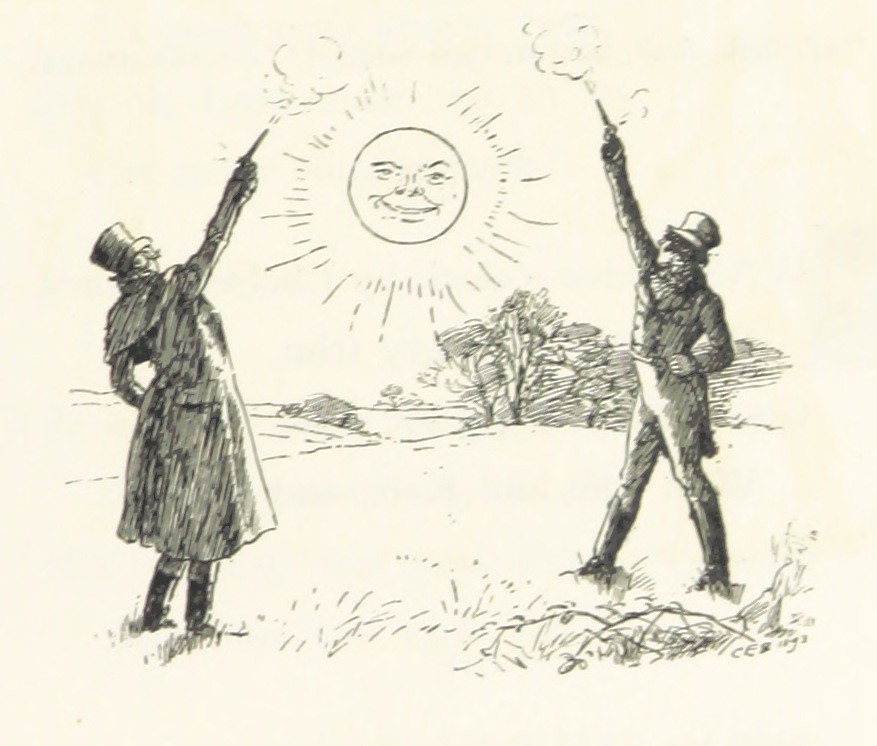

A duel did not require a winner or loser. In fact, they did not require bloodshed at all. The mere act of standing on the dueling ground and being willing to die for one’s honor sufficed for most. Many duelists threw away their shots—either by shooting into the ground in front of themselves or shooting well above their opponent. Many who engaged in duels often missed their targets on purpose—valuing life over death but demonstrating that each was willing to die for his honor. Hamilton probably did just that.4

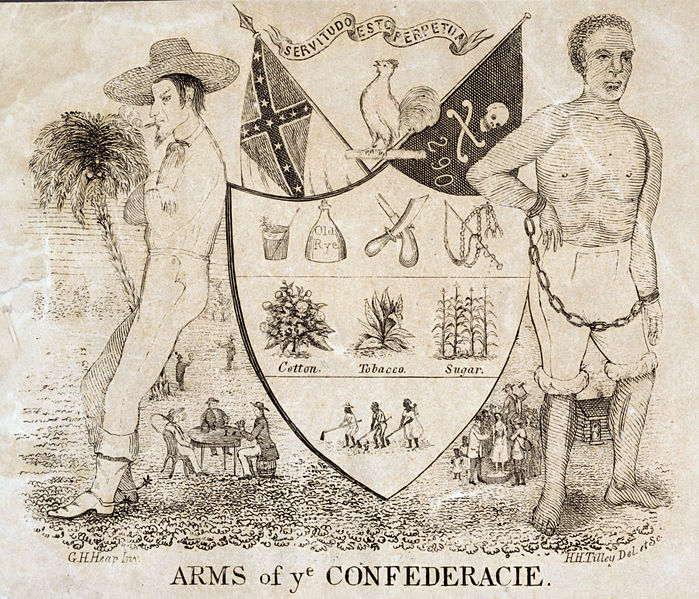

In the decades leading to the Civil War, dueling became another distinction between North and South. Northern states began to outlaw the practice while it remained an important part of Southern culture. Southern congressmen used the threat of deadly violence to great effect by stifling congressional debate and preventing any political road to the end of slavery.

After an 1838 duel in which Representative William Graves of Kentucky killed Representative Jonathan Cilley of Maine, Congress outlawed dueling in Washington, D.C. By 1859, 18 of 33 states had made dueling illegal.5

Nevertheless, partisanship in American politics grew stronger in the years leading to the Civil War. That partisanship often led to personal insult and perceived affronts to personal honor and notions of masculine identity. House clerks documented several fistfights, the brandishing of knives and guns, and even a caning, all attempts at silencing voices seen as threatening to sectional political values.6

Though Hamilton and Burr occupied positions at the highest levels of American politics, their story was never really about politics or policies. Instead, duels resulted from bruised feelings and thin skins.

While politicians today no longer square off with pistols, recent threats of violence made by politicians, and actual acts of violence as when Congressman Greg Gianforte (R-MT) assaulted a reporter in 2017, remind us that some political egos are as fragile as ever.

1 Joanne B. Freeman, Affairs of Honor: National Politics in the New Republic (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2002), 188.

2 For more on the intricacies of honor in the Hamilton-Burr duel, see Freeman, Affairs of Honor, 189-198.

3 "Letter From Alexander Hamilton to Aaron Burr, 20 June 1804."

4 For an outline of the evidence surrounding the possibility of Hamilton wasting his shot see: Hamilton’s “Statement on Impending Duel with Aaron Burr,” and Joseph J. Ellis, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (Knopf, New York, 2000) pp. 30-31.

5 For more on the effect of the Cilley-Graves duel on Congress, see Chapter 3 of Joanne B. Freeman's The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to the Civil War (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018).

6 For more on how House clerk B.B French documented congressional violence leading to the Civil War, see Freeman, The Field of Blood.