Unprecedented. That word has been tossed around a lot since Donald Trump decided to run for president. Whether or not it has been overused, it certainly applies to the volume and scope of the scandals in which he has been embroiled since 2016. Presidential malfeasance is not new, but as historian Marc Horger traces, Trump's scandals have wrapped up all the different kinds of disrepute into one tangled web to an extent that is, well, unprecedented.

Having trouble keeping up with all the overlapping accusations of wrongdoing and scandal swirling around the Trump administration? Exhausted just trying to stay factually up to date? Twitter feed got you down?

Well, you aren’t imagining things. It isn’t just that the Trump administration is prone to scandal. The Trump administration is prone to an astounding pace and variety of scandal. Some incidents are primarily about sex; some are primarily about corruption and personal enrichment; others challenge the basic norms of American governance.

Sometimes it seems as if the administration is collapsing the history of American political scandal down to a singularity, offering the equivalent of a Major League Baseball “condensed game” of American political wrongdoing.

A brief tour of past presidential scandals can help us sort out how the Trump administration is replaying the greatest hits of American political ignominy.

The High Bar

The ubiquitous, unfathomable ur-scandal of the Trump administration, at least thus far, is the role played by Russian intelligence in the 2016 election and the realistic possibility that subterranean ties between Trump and Russia extend as far back as the late Soviet era.

Previously, the most outlandish and perplexing scandal in American political history had been one of the earliest: the treason case against Aaron Burr.

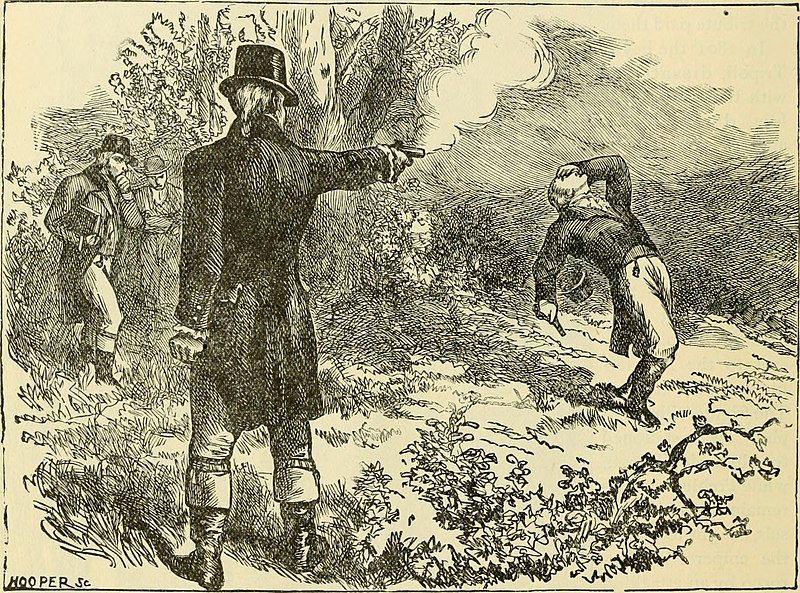

A 1901 depiction of the 1804 dual between Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr.

Burr, an ambitious and successful New York politician, helped build both the Tammany Hall political machine in New York City and the national Jeffersonian Republican coalition, and as a result wound up Thomas Jefferson’s first vice president. He was never particularly trusted or valued in the role, however, and was dropped from the ticket in 1804.

Burr was nevertheless busy. He failed in a bid for governor of New York, a bid linked to a secession scheme by New England Federalists. Blaming his old rival Alexander Hamilton for the failure, he shot and killed Hamilton in a duel with which the world is still familiar. Burr then spent two years pursuing allies for a filibustering scheme he hoped would make him ruler of some portion of Texas and/or the trans-Appalachian west. Jefferson finally had Burr arrested and tried for treason in 1807.

Burr’s trial, however, ended in an embarrassing loss for Jefferson. The main evidence against Burr came from James Wilkinson, a co-conspirator widely believed to be hired by the Spanish government (a fact now known to be true). The trial was presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall, Jefferson’s main political antagonist, who interpreted “treason” so narrowly as to separate intent or conspiracy to commit treasonous acts from the actual commission of such acts. Burr was acquitted. He moved to Europe, where he continued to seek support for wild schemes against Spanish possessions in North America.

Though not a “presidential scandal” in the sense that it involved presidential misconduct, the outcome of the Burr Conspiracy had a significant long-term impact on how the American political system would subsequently address high-level wrongdoing. It set the legal and political bar for treason very, very high.

Another of Jefferson’s political miscalculations, the failed impeachment of Supreme Court justice Samuel Chase, had a similar effect. If, at some point, the judicial and/or legislative branches take aim at Trump wrongdoing, they will face the high bar set during the Jeffersonian period.

Sex, Honor, and Propriety

Just as Trump/Russia is a cluster of related scandals rather than a single node of wrongdoing, so does Stormy Daniels stand in for a whole category of Trump infidelity and sexual misconduct.

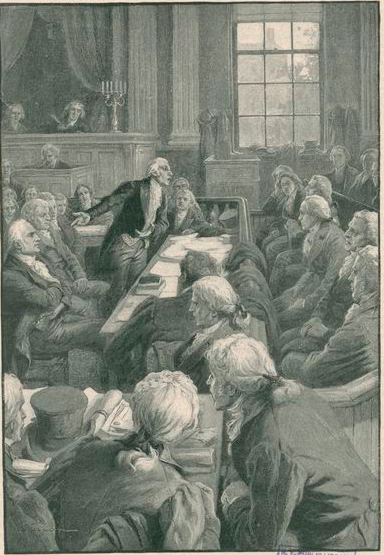

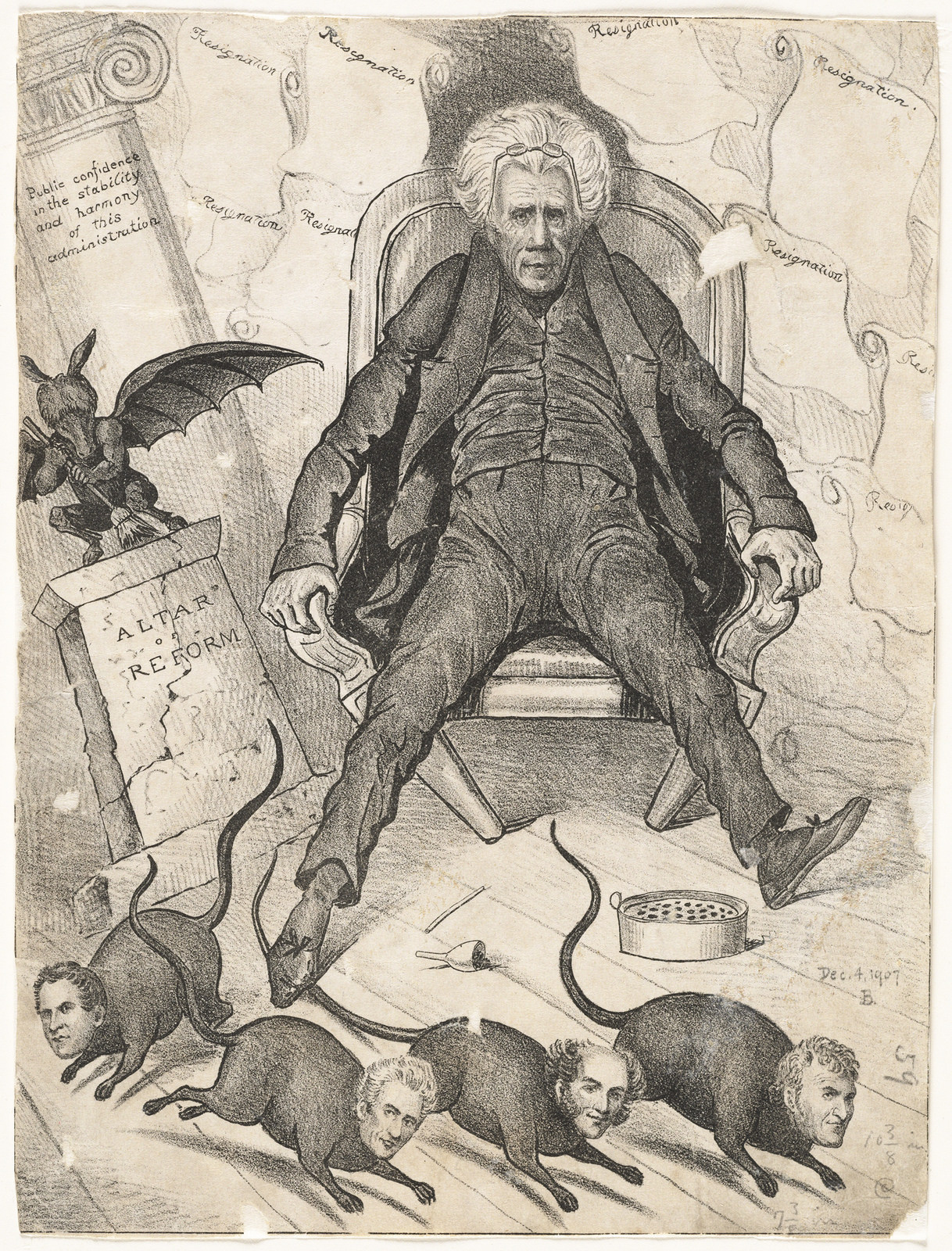

An 1836 satire about President Andrew Jackson and his cabinet.

To the extent that accusations of sexual misconduct have shaped previous presidencies, however, they have turned less on the morality of the conduct in question and more on the ability of a president or candidate to make his version of contested events the master narrative.

President Andrew Jackson, for instance, imbued every moment of his life with a comically exaggerated sense of honor—so much so that his first administration was dominated by the Petticoat Affair, a scandal over the sexual reputation of the wife of one of his cabinet members.

John Eaton, the Secretary of War and a friend of Jackson’s from Tennessee, had just married Peggy O’Neale, a young widow well known in Washington. The marriage was disreputable by the standards of the day; O’Neale’s previous husband, John Timberlake, had not been dead long, and many in Washington believed that she and Eaton had been conducting an affair while Timberlake was still alive. Respectable Washington women refused to socialize with her.

This infuriated Jackson, whose own wife, Rachel, had long been accused of similar impropriety, and had just passed away. Incapable of interpreting any occurrence or event except through the lens of loyalty to himself, Jackson attempted to defend O’Neale’s honor with the same combination of verve and recklessness he used to defend his own. “She is chaste as a virgin!” he allegedly declared in a cabinet meeting called to demand that the wives of his cabinet members socialize with the Eatons.

When this failed, the only solution turned out to be mass resignation of the cabinet. The big loser was John Calhoun, whose wife Floride was at the center of the anti-Eaton cabal. The big winner was Martin Van Buren, who, as a widower, had avoided the problem altogether. He became Jackson’s preferred political successor and the heir to the Democratic Party itself.

Subsequent presidential sex scandals have been more salacious but ultimately less transformative of the path of American politics.

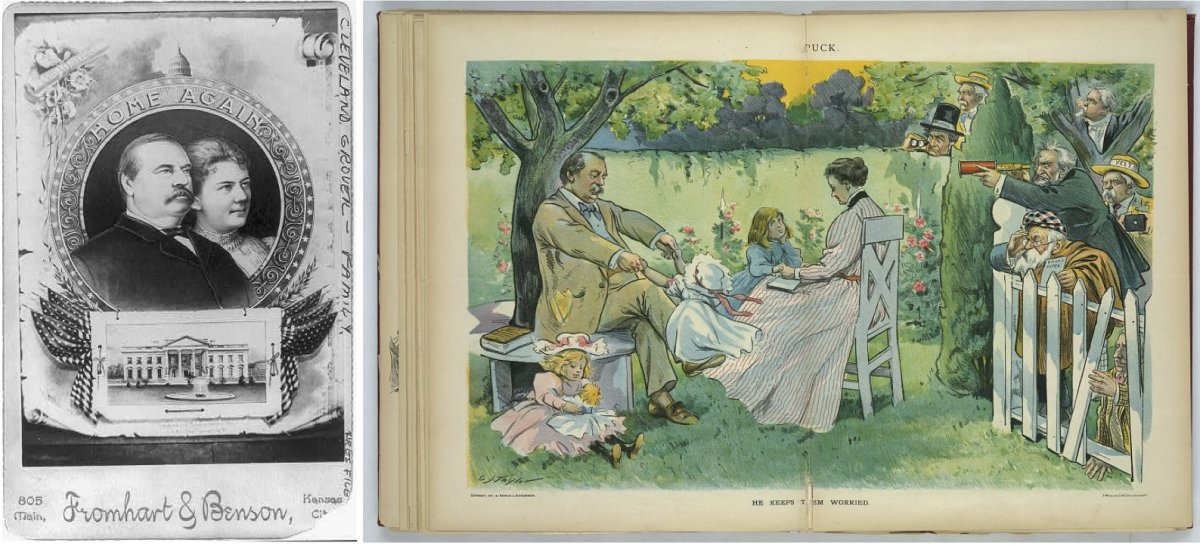

An 1884 cartoon referencing President Grover Cleveland's affair with Maria Halpin.

In 1884, Grover Cleveland ran for president as a bachelor. His opponent, James Blaine, was widely regarded as vulnerable to accusations of corruption, so Democrats positioned Cleveland as “Grover the Good” and ran him as a symbol of personal probity.

During the campaign, however, accusations surfaced that Cleveland had fathered an illegitimate childten years earlier. Cleveland quickly admitted to an affair with the woman in question, a Buffalo widow named Maria Halpin. He claimed, however, that any number of other prominent men in Buffalo might also have been the father, and that, since he was the only bachelor among them, he had accepted paternity as a gesture of gallantry and arranged for the child to be adopted by a respectable family.

An 1893 portrait of President Cleveland and his wife above the White House (left). A print showing President Cleveland and his wife playing with their children in their backyard while reporters watch (right).

In the context of the sexual politics of the 1880s, this was audacious spin. It simultaneously positioned Cleveland as a champion of moral rectitude and slandered everyone else, especially Halpin. She responded with accusations that the adoption had been coerced and that Cleveland had paid a settlement of $500 to make the matter go away.

Cleveland nevertheless won a close election, then flipped the Victorian sexual script a second time by marrying while in office. Cleveland is now famous mostly for having served two non-consecutive terms.

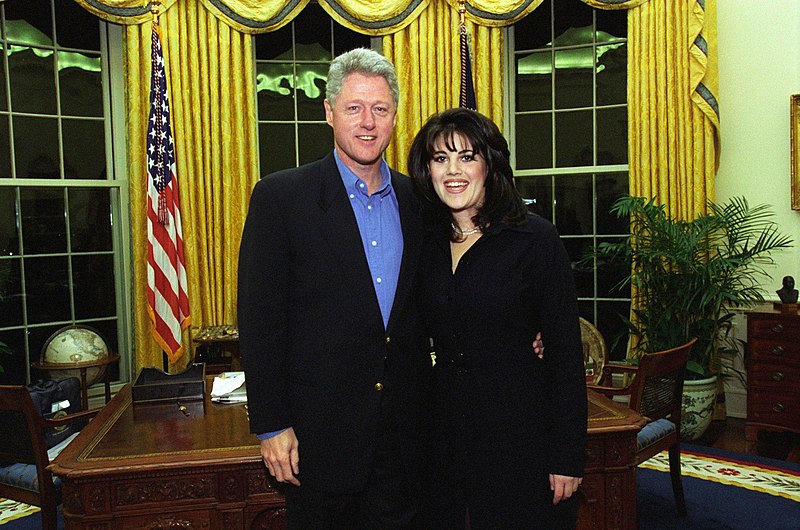

Bill Clinton similarly survived accusations of sexual impropriety, though in his case the battle was more complex and more closely fought.

The intended site of the Whitewater Development Corporation along the Whitewater River in Arkansas.

The investigative dominos that eventually triggered the Monica Lewinsky sex scandal began with an obscure real estate failure in Arkansas. While governor of Arkansas, Clinton invested in the Whitewater Development Corporation, a local real estate project that failed along with its associated savings and loan, Madison Guaranty. Madison Guaranty was owned by close political associates and, it turned out, engaged in a number of financial irregularities. When Clinton ran for President in 1992, these irregularities became the subject of intense public scrutiny.

So did Clinton’s personal life, as he had a reputation for philandering and infidelity.

In 1994, an Arkansas state employee named Paula Jones sued Clinton for sexually harassing her several years earlier, when he was still governor of Arkansas. The Jones case, along with a number of other accusations against Clinton, eventually came under the purview of special prosecutor Kenneth Starr, who had initially been appointed to investigate Whitewater, but ultimately targeted a variety of Clinton scandals and sub-scandals.

President Bill Clinton with White House intern Monica Lewinsky around 1995.

The release of the Starr Report was one of the first major news events impacted by the emergence of the Internet (or as Clinton liked to call it, “the Information Superhighway”). CNN broke the news by filming its lead reporter sitting at a computer terminal waiting for the report to be published online.

Starr’s report concluded that Clinton had committed perjury and obstruction of justice when, in his deposition in the Jones case, he denied sexual contact with Lewinsky. Starr’s report also contained accounts of the sexual contact in question.

President Bill Clinton denying allegations that he had sexual relations with Lewinsky in 1998.

Clinton was impeached in 1998, but not convicted by the Senate. His public approval ratings remained high throughout the scandal, and the Democrats made gains in the 1998 Congressional midterms.

On the Take

One set of Trump scandals that lacks useful historical analogy are the overlapping emolument and personal and/or familial enrichment activities which suffuse the daily business of the White House. Evidence of financial corruption and/or influence peddling in an administration once doomed the historical reputation of a presidency even if the president himself did not appear to benefit personally.

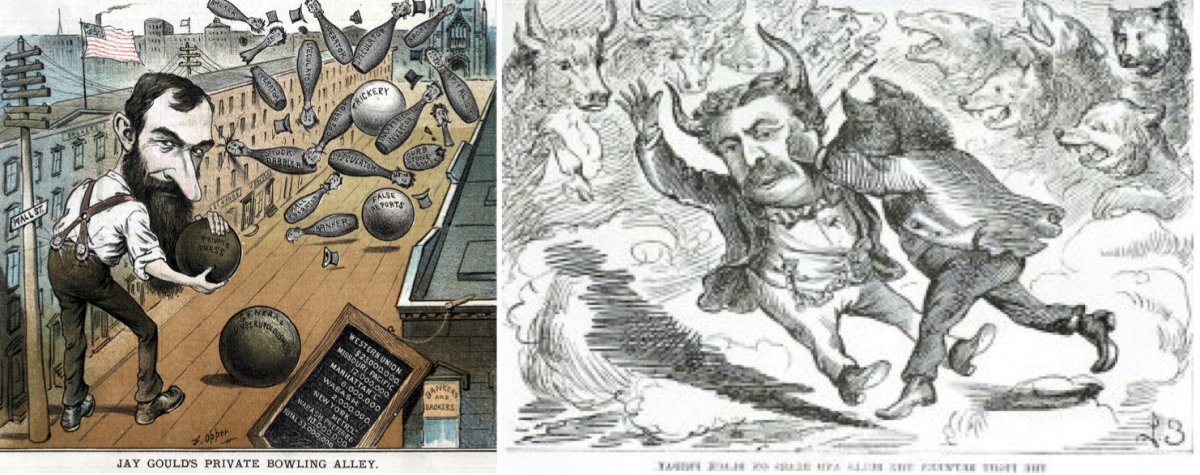

The Grant administration,for instance, featured an eclectic range of corruption scandals, none of which directly implicated Grant himself, but ruined his historical reputation nonetheless.

An 1882 cartoon showing Jay Gould on Wall Street, depicted as a bowling alley (left). A cartoon depicting James Fisk being knocked down by a bear market on Black Friday 1869 (right).

In 1869, Wall Street financiers Jay Gould and James Fisk attempted to corner the market in gold. Their scheme hinged on convincing the U.S. Treasury to temporarily suspend its policy of releasing gold into the marketplace, so as to artificially limit its supply and permit the corner.

Fisk and Gould believed they had successfully lobbied Grant into the scheme by convincing him that suspension of gold sales would be good for crop prices; they took the additional precautions of paying Treasury officials for inside information and attempting to bribe assorted Grant confidants and family members.

Once Grant realized the nature of the scheme, he ordered the Treasury to sell gold and break the corner. The scandal, however, contributed to his reputation as personally honest but malleable and naïve in the face of pressure from rich friends.

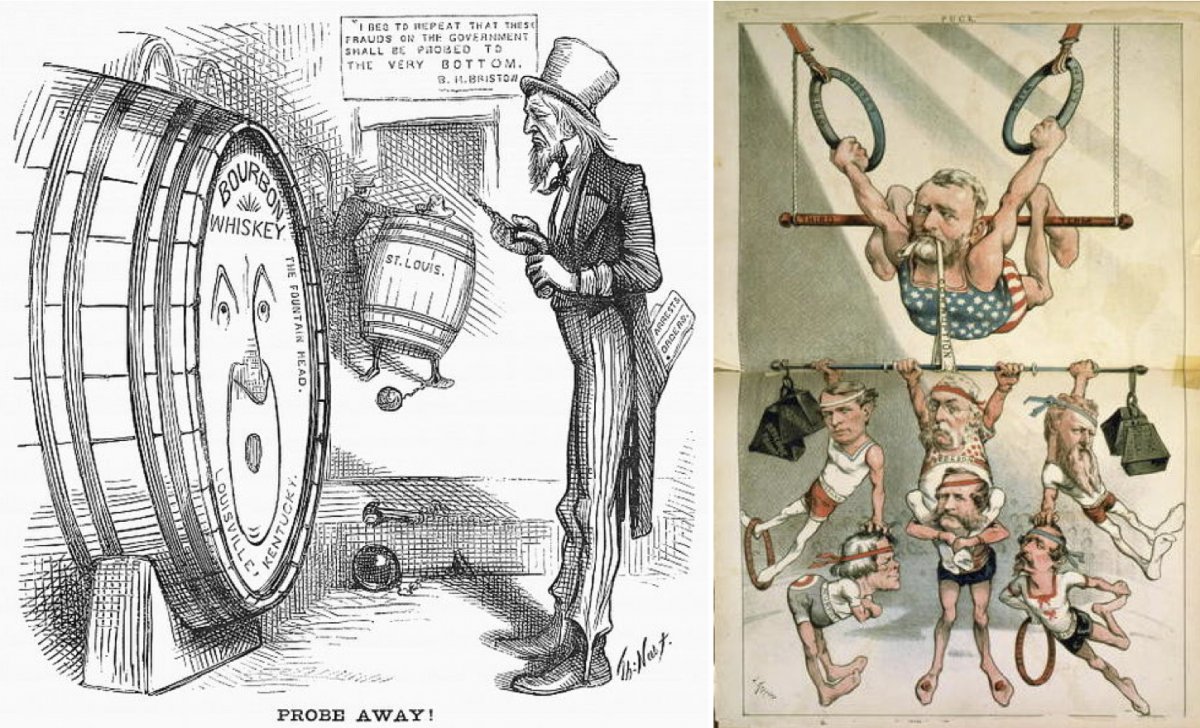

n 1876 Thomas Nast cartoon on the Whiskey Ring (left). An 1880 cartoon showing Ulysses S. Grant on a trapeze holding onto a “third term,” “whiskey ring,” and a “Navy ring” with “corruption” in his mouth (right).

Additional Grant scandals included the Whiskey Ring, in which Grant’s private secretary Orville Babcock was implicated in a kickback scheme involving evasion of the federal excise tax on spirits; the New York Custom House Ring, in which administration appointees helped importers evade customs duties; kickbacks to Secretary of War William Belknap in exchange for monopoly rights at western trading posts; and a bribery scandal in the Department of the Interior involving fraudulent land grants.

For many years, this combination of scandals contributed to Grant’s ranking near the bottom of historians’ ratings of Presidents, though his reputation has recently improved due to re-evaluation of his role in Reconstruction.

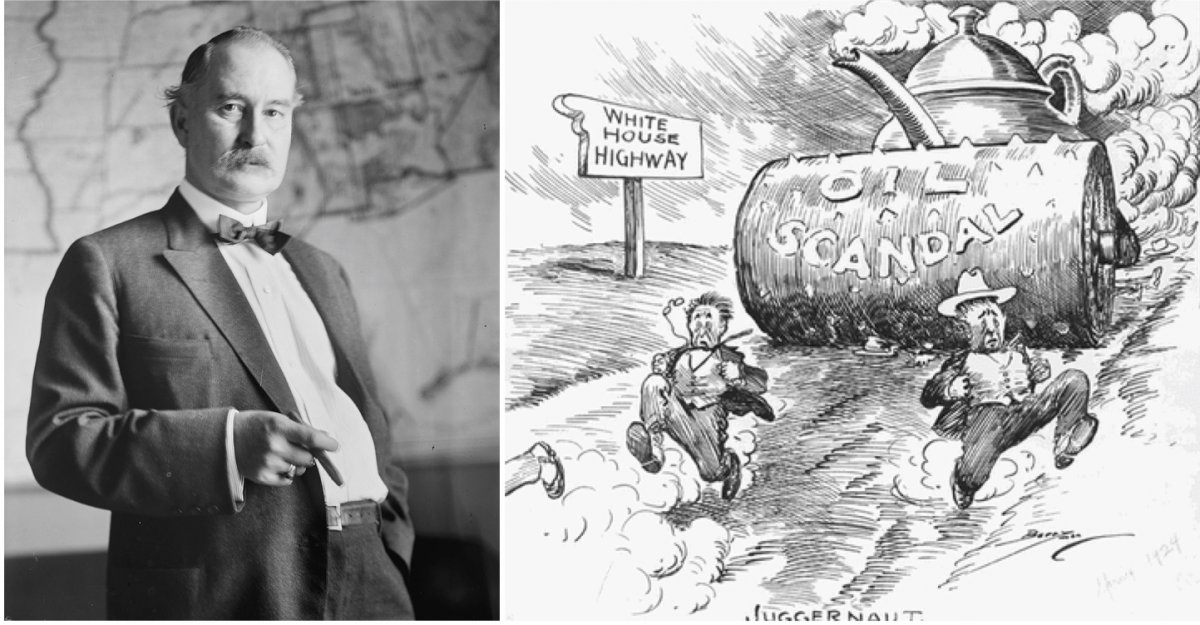

In 1929, former Secretary of the Interior Albert B. Fall became the first U.S. cabinet official sentenced to prison (left). A 1924 cartoon showing Washington officials running down an oil-slicked road to avoid the Teapot Dome scandal (right).

Harding, like Grant, was personally unenriched by these events, but Harding, like Grant, suffered in the eyes of historians as a symbol of a particular style of political corruption regarded as characteristic of his era.

Other members of the so-called “Ohio Gang” surrounding Harding, including Attorney General Harry Daugherty and Director of the Veterans’ Bureau Charles Forbes, were also credibly charged with corruption while in office. In 1927, a few years after Harding’s death, one of his mistresses, Nan Britton, published a book detailing their affair, including the accusation that Harding was the father of her daughter. This claim was confirmed by DNA evidence in 2015.

Did the President do that? Can the President do that?

As yet, sex and money have failed to fell a Presidency. Only a Constitutional crisis has been sufficient.

The alpha and omega of American political scandals remains Watergate, the only one to both compel the resignation of a President and permanently alter the English language.

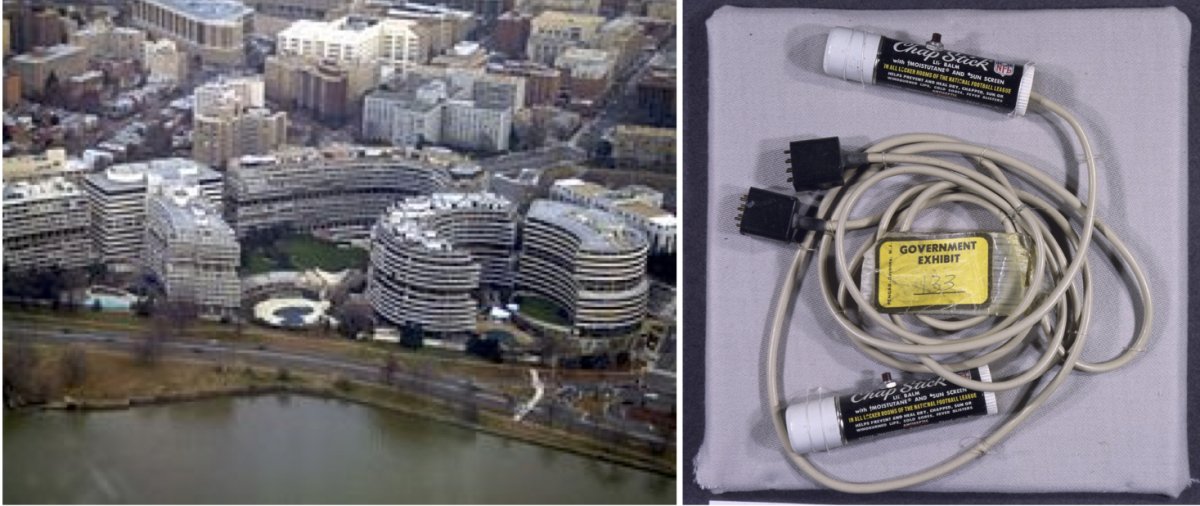

The Watergate Complex in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood of Washington, D.C. (left). Chapstick tubes outfitted with small microphones used during the Watergate burglary and discovered in a White House safe (right).

In June of 1972, five men were arrested in the offices of the Democratic National Committee, located in the Watergate complex, while in the process of bugging DNC phones. It soon emerged that the burglars had been financed by money tied to Nixon’s re-election committee, and were part of a larger network of political espionage and sabotage activities. These revelations nevertheless had little impact on the outcome of the election, as Nixon cruised to one of the biggest landslide victories in history.

Nixon’s second term, however, was immediately consumed by efforts to cover up the White House’s role in and knowledge of the burglary.

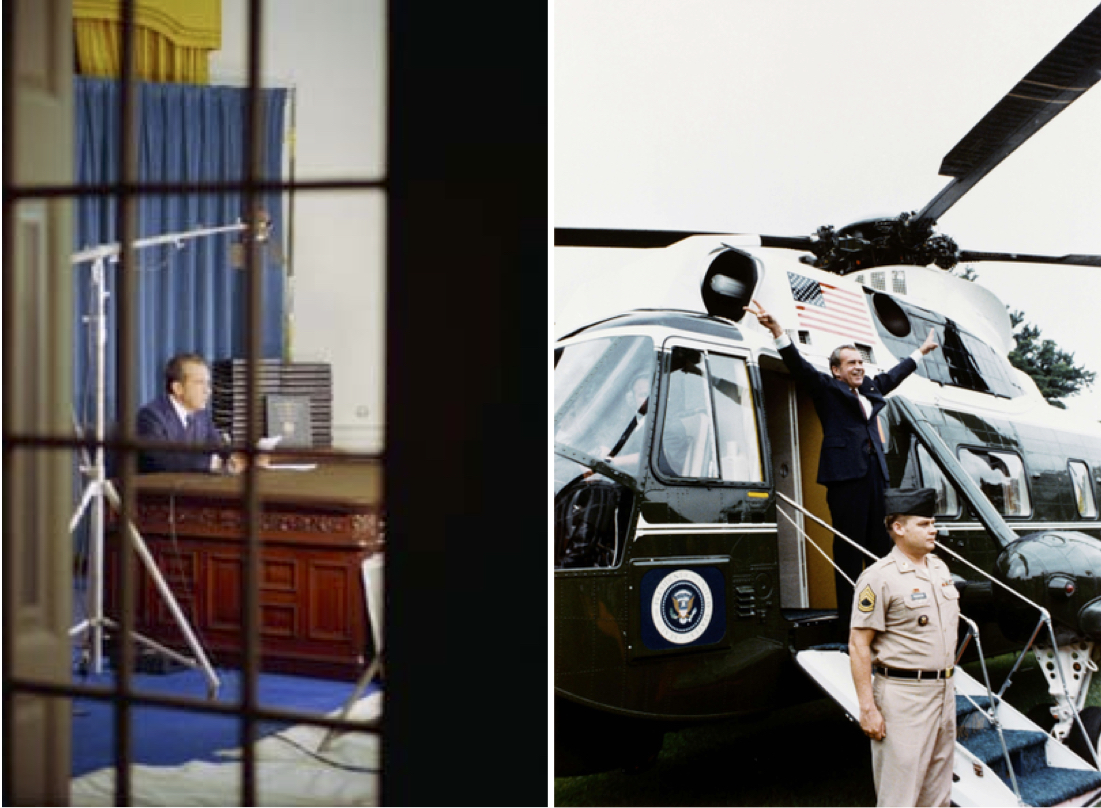

A view of President Richard Nixon from outside the Oval Office addressing the nation on April 29, 1974 (left). President Richard Nixon boarding Army One after resigning on August 9, 1974 (right).

Televised Senate hearings began in May 1973, by which time a special prosecutor had been appointed and several major administration figures had already resigned. The Senate hearings revealed the existence of an automated taping system in the White House; the tapes, once made public, confirmed the extent of Nixon’s complicity in both systematic abuse of executive power and subsequent efforts to obstruct justice.

His effort to halt the investigation by ordering the firing of the special prosecutor—the Saturday Night Massacre—ultimately failed. He resigned in August 1974. Meanwhile, Nixon’s vice president, Spiro Agnew, had been forced to resign in October 1973 as the result of an entirely separate scandal related to kickbacks on construction contracts Agnew had accepted while governor of Maryland.

President Nixon’s resignation address on August 8, 1974.

Watergate remains a canonical trope of American culture, not just American politics. It spawned the greatest journalistic mystery of the twentieth century—who was “Deep Throat,” the informant—and is the central plot device of at least five major motion pictures and an episode of Futurama. Its cultural power came, ultimately, from its moral legibility. Even Nixon understood: people have gotta know whether or not their President’s a crook.

Subsequent executive branch scandals of similar Constitutional importance have proved less legible. Take, for example, the Iran-Contra affair, a scandal with a hyphenated name, and a separate and unique scandal on each side of the hyphen.

On the “Iran” side, the Reagan administration in 1985 engaged in secret negotiations with the Iranian government in an effort to secure the release of seven American hostages being held in Lebanon by Hezbollah. These negotiations led to arms transfers to Iran via Israel. At the time, Iran was one of six countries on the American list of “state sponsors of terrorism.”

President Ronald Reagan addressing the nation regarding Iran-Contra on November 13, 1986.

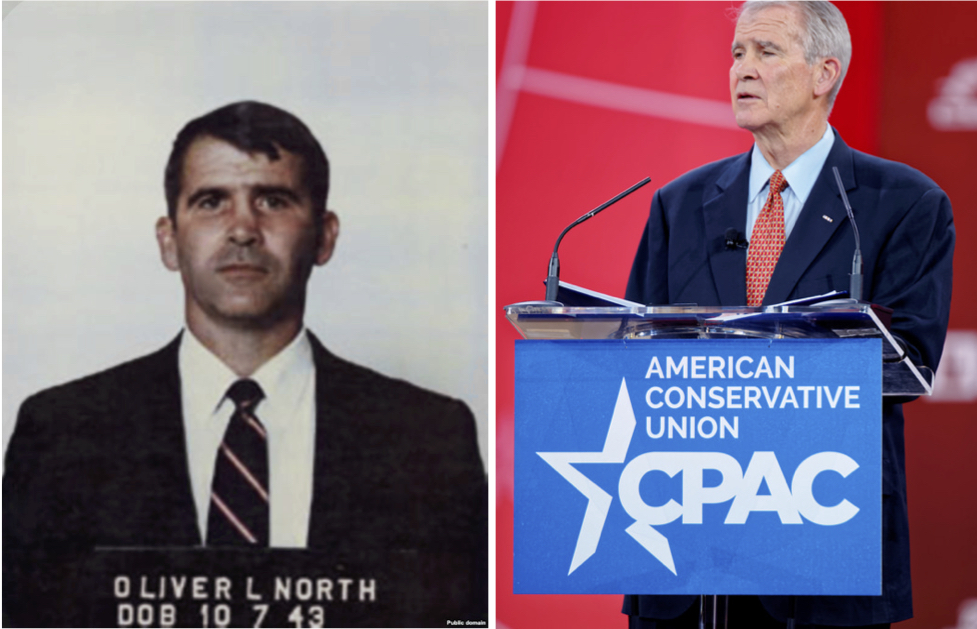

Meanwhile, the administration was also covertly supporting the “Contras,” anticommunist guerrillas in Nicaragua, in violation of the recently passed Boland Amendment. The hyphen, so to speak, was Oliver North, a National Security Council deputy instrumental in funneling proceeds from the Iranian arms sales to the Contras—and in destroying evidence of the linkage once the arms sales became public.

As with Watergate, presidential knowledge of and/or culpability in the crime was the underlying question of the scandal. This ultimately applied to two presidents, as George H.W. Bush was also potentially implicated.

A mug shot of Oliver North after his 1987 arrest (left). North at the Conservative Political Action Conference in 2015 (right).

Also like Watergate, the Constitutional limits of executive power were placed on national trial. Iran-Contra nevertheless proved less obviously morally or legally clear. Despite numerous indictments stemming from the scandal, Reagan’s reputation largely survived, and he remains an iconic hero to many conservatives—as, to a certain extent, does North, who was recently elected president of the NRA.

The Valerie Plame Affair proved less potent than Watergate, despite presenting similar questions about abuse of executive power.

In 2003, George W. Bush ordered an invasion of Iraq on the stated grounds that the regime of Saddam Hussein had sought weapons of mass destruction in violation of U.N. resolutions. As partial evidence, the administration claimed that Iraq had sought to obtain yellowcake, partially enriched uranium, from Niger.

After the invasion, however, a former American diplomat named Joseph Wilson wrote an op-ed in the New York Times calling the Niger story into question, and suggesting that the administration’s evidence for war had been falsified. A week later, Wilson’s wife, Valerie Plame, was outed as a CIA agent in a leak to Washington Post columnist Robert Novak.

Plame’s status as a CIA asset was classified, and a special prosecutor was appointed to investigate the leak. Scooter Libby, chief of staff for Vice President Dick Cheney, was eventually convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice, not for the leak itself, but for lying to the FBI about his contacts with reporters. Conservatives demanded his pardon; Cheney’s relationship with George W. Bush was reportedly damaged permanently by Bush’s refusal to grant one.

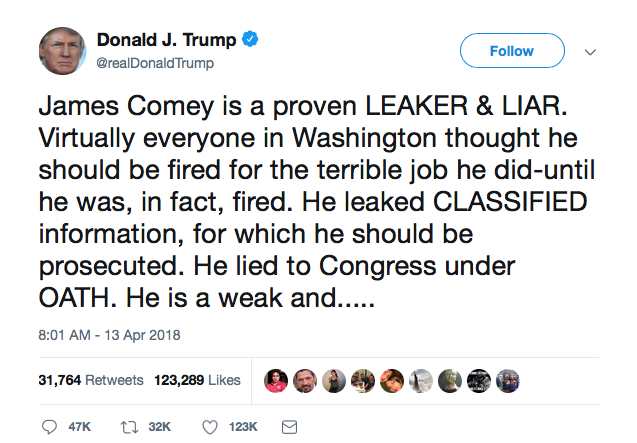

Donald Trump, however, pardoned Libby on April 13, 2018. Also on April 13, Trump called James Comey—who, as deputy Attorney General in 2003, had appointed the Plame special prosecutor, and who, as FBI director in 2017, was fired by Trump over his role in the investigation into Russian meddling in the 2016 election—a “LEAKER & LIAR” on Twitter.

An April 2018 Tweet from President Donald Trump about James Comey.

The truth of this claim remains under investigation by Robert Mueller, special counsel for the Department of Justice.

Whether or not the Mueller investigation yields constructive action against any of the above outrages may depend on pace. What happens when wrongdoing accrues at a rate faster than it can be investigated?

Read and Listen to Origins for more on U.S. politics: Controversial SCOTUS Nominees; Media and Politics in the Age of Trump; Women Who Ran before Hillary; “Big Government” in American History; The American Two-Party System; “Class Warfare” in American Politics; American Populism; Presidential Elections in Times of Crisis; The 2016 Presidential Election; Women in American Politics; America's Post-Election Political Landscape; Puerto Rico and the United States; and America's Infrastructure Challenge.

For explorations of the relationship between Trump and Russian interests, see:

Seth Hettena, Trump and Russia: A Definitive History, Brooklyn: Melville House, 2018.

Michael Isikoff and David Corn, Russian Roulette: The Inside Story of Putin’s War on America and the Election of Donald Trump, New York: Hachette Book Group, 2018.

For a succinct and well-contextualized account of Burr’s western adventures, see:

Nancy Isenberg’s Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr, New York: Viking, 2007, pp. 271-366.

For an account of the role of scandal in Grant’s presidency:

Ron Chernow, Grant, New York: Penguin Press, 2017, esp. pp. 672-81 and 796-837.

On Watergate, see:

Stanley I. Kutler, The Wars of Watergate: The Last Crisis of Richard Nixon, New York: Knopf, 1990 and Abuse of Power: The New Nixon Tapes, New York: Free Press, 1997.

On Iran-Contra and its relationship to Reagan’s historical legacy, try:

Sean Wilentz, The Age of Reagan, New York: Harper Perennial, 2008, pp. 209-244.

For a good account of the Clinton scandal nexus:

Jeffrey Toobin, A Vast Conspiracy, New York: Random House, 1999.

For accounts which explore how the historical memory of Presidential scandals changes over time, see:

Phillip G. Payne, Dead Last: The Public Memory of Warren G. Harding’s Scandalous Legacy, Athens: Ohio University Press, 2009.

Joan Waugh, U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009.