As we debate what is appropriate for the federal government to do in American life, we should pay close attention to the role it has played in American history

Americans love to hate their government. And they are just as reluctant to acknowledge the extent to which the actions of the federal government have created the prosperous society we live in today. As Secretary of Defense William Cohen once quipped: “Government is the enemy until you need a friend.” This month historian Steven Conn explores how Americans have benefited from that friendship.

Read more on current events in American Politics: The American Two-Party System; “Class Warfare” in American Politics; American Populism; Immigration Policy; Presidential Elections in Times of Crisis; Mass Unemployment; and American Political Redistricting.

Listen to the history podcast: The Contentious ACA

Check out a lesson plan based on this article: Federalists vs. Anti-Federalists: A Debate that Rages On and Big-time Bureaucratic Brouhaha

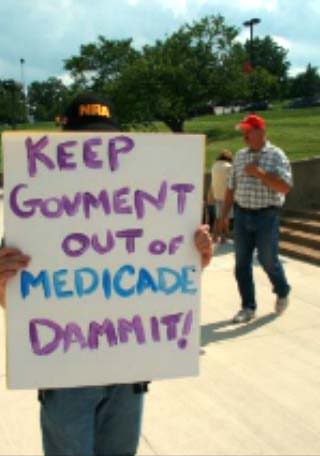

We live at a moment in American politics when there has never been more anger directed toward “big government,” and that anger has boiled over during the last several election cycles. For some of those angry Americans, the federal government has usurped the role of state and local governments ever since the New Deal of the 1930s. Others fulminate that anything the federal government does amounts to an existential threat to their liberty.

So with another round of federal elections looming, let’s start with three vignettes to help illustrate the problem Americans have understanding the role of the federal government in American life:

1) At a town hall meeting in Simpsonville, South Carolina hosted by Republican Congressman Robert Inglis in the summer of 2009, an angry senior citizen thundered: “keep your government hands off my Medicare.”

2) In April 2013, Kentucky Republican Senator and Tea Party darling Rand Paul traveled across Washington, D.C. to deliver a speech to students at Howard University, perhaps the most venerable of the nation’s historical black colleges. He told them, among other things, that “big government” had failed African Americans.

3) In July 2008 David Koch, billionaire energy magnate and funder of libertarian political causes, pledged $100 million to the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center in New York City. In return the theater was renamed “The David H. Koch Theater.”

The first of these scenes is a risibly obvious example of the ignorance some Americans have about the place of government programs even in their own lives, and plenty of people have poked fun at that sputtering geriatric from South Carolina. Even Congressman Inglis, no friend of the federal government or of the Obama administration, seemed a little exasperated: “I had to politely explain,” he told a reporter afterward, “that ‘Actually, sir, your health care is being provided by the government.’ But he wasn’t having any of it.”

Senator Paul’s speech in front of a group of African American college students was a breathtakingly obtuse misunderstanding of the role the federal government has played in the history of black civil rights. Senator Paul regularly denounces the reach of the federal government as an intrusion on the rights of the states, but he can’t quite acknowledge that “states rights” was responsible for the creation of Jim Crow segregation, nor can he acknowledge that our system of American apartheid was broken, finally, in large part because of the actions of the all three branches of the federal government.

My third vignette about how we misunderstand government resides in the department of irony. David Koch is apparently a big fan of opera and ballet and he has been a regular patron at Lincoln Center over the years. His philanthropy was, at one level, an act of generosity toward the arts that he loves.

At another level, of course, it gave him the opportunity to create his own legacy by putting his name on what is arguably the center of the cultural life of New York, which is arguably the center of the nation’s cultural life. A kid from Wichita, Kansas, Koch wanted to buy himself a piece of New York cultural cachet.

But Lincoln Center itself was created as part of a large-scale urban renewal project in the early 1960s and partially funded by the federal government. Whether he recognized it or not, David Koch put his name on a pure piece of “big government.”

These three stories – and I could have chosen any of a dozen others from the past few years – demonstrate that there has never been more confusion about what the federal government does, how it does it, and why.

At its root, that confusion is historical: the three people at the center of my little stories – the angry senior, the angry senator, and the angry billionaire – each misunderstand the role the federal government has played in creating the nation we inhabit today, whether in health care, civil rights, or cultural achievement.

In fact, the federal government has from its inception been an active force in American life across a wide range of sectors. An activist federal government is as old as the nation itself, and that history demonstrates how seriously the federal government has pursued its Constitutional charge “to promote the general welfare.”

In 1996 former Senator and Secretary of Defense William Cohen (R-Maine) famously quipped, “Government is the enemy until you need a friend.” And for over two hundred years many Americans—from the largest of businesses to the most dispossessed of citizens—have benefited in all sorts of ways from that friendship.

Government Intervention, American Tradition

When the First Congress of the United States assembled in 1789, the first major piece of legislation it passed involved an intervention in the economy and raising taxes. The Hamilton Tariff, named because it was championed by Alexander Hamilton, the first Secretary of the Treasury, slapped a tax on a range of imported manufactured products.

The tariff had two goals: first, it was designed to raise revenue so the new government could pay off its debts; and second, it was supposed to stimulate domestic industry by making imported goods more expensive. Call it an economic stimulus package, 18th-century style. And by and large the Hamilton Tariff achieved its goals. Money was raised and American producers, especially in northern urban centers, grew.

The Hamilton Tariff was by no means an anomaly. In fact, it is worth remembering that the Constitution itself was written and adopted so that the federal government could take a more active role in promoting American economic growth (the Articles of Confederation having proved a miserable failure for the economy).

Just three years later, in 1792, Congress created what was then a huge new national program when it passed the Postal Act. The act didn’t merely create a postal system, the most important means of communication at the turn of the 19th century. It guaranteed privacy for our mail and it permitted newspapers to travel through the post.

The Postal Act helped tie a far-flung nation together and permitted news to travel even into the American hinterland. Our 1st amendment guarantees of freedom of expression and freedom of the press are splendid abstract principles. The Postal Act made those principles real for Americans and allowed them to be put to work.

Across the 19th century, the federal government acted in a variety of ways to stimulate American growth. Once he became president, Thomas Jefferson, perhaps the founder most suspicious of big government, used the power of the office to expand the nation through the Louisiana Purchase. He imagined that this government acquisition would provide farmland for countless generations of American yeoman farmers.

His ideological successor, Andrew Jackson, used federal authority to remove Native people from their homeland, marching them brutally on the Trail of Tears. Thus did he clear space for southern farmers and slave owners to prosper.

The Civil War certainly marks the most dramatic expansion of federal power in the 19th century. As Americans have been marking the 150th anniversary of that conflict, we have been reminded that in order to prosecute the war President Abraham Lincoln instituted military conscription, suspended habeas corpus rights, and started printing paper money. It is worth stating forthrightly: this creation of big government was necessary to end the institution of slavery. Had we left the question to the states, as Southerners regularly demanded, slavery might have lasted a great deal longer.

But fighting the war was not all Congress did during those years. In 1862, Congress enacted three pieces of legislation intended “to promote the general welfare” that still resonate today.

When Congress wanted to facilitate the expansion of the nation westward and to stimulate the transportation network necessary for this, it chartered the Union Pacific and Central Pacific railroad corporations. The terms of this charter should strike us today as extraordinary. Congress loaned money to these private corporations on very generous terms. Even more than that, it granted free land to the two railroads—to the tune of 20 square miles for every mile of track laid! —that they could turn around and sell to raise capital.

The first transcontinental railroad was completed in 1869, and it simply wouldn’t have happened without that public support. The railroads did not build themselves.

At the same moment, Congress passed the Homestead Act. That act enabled settlers in the trans-Mississippi to lay claim to 160 acres each. If they farmed it for 5 years, the land was theirs. For free! (The Homestead was joined by other acts that opened up ranching and timbering as well.) The Homestead Act became one the greatest land giveaways in human history.

It turns out that those rugged pioneers of American myth traveled west on federally subsidized railroads to settle land given to them by the federal government. And once out in the west, those railroad networks and those settlers were protected by federal troops who, between 1865 and 1890, engaged in continuous military action against native people. This is how the west was won.

Congress wasn’t finished in 1862. The third of its big initiatives in that year was the Morrill Land Grant Act. This act gave federally owned land to individual states in exchange for the promise that states would sell or use revenue from the land to establish universities. Collectively we call them “the land grants” and they amount to nothing less than the greatest democratization of higher education ever.

We can measure the economic impact of those railroad charters and of the Homestead Act, but the value to the nation—economic, social, cultural, and intellectual—of the land grants is incalculable. I say this from personal experience because I am lucky enough to teach at one.

Transportation, agriculture, education, communication.

All four were profoundly reshaped by the actions of the federal government in the 19th century because the American people, through the elected representatives they sent to Washington, believed this was how to promote the general welfare.

The Roosevelt Revolution (TR, That Is)

In the late 19th century, the federal government continued to help the growth of American business in any number of ways. Indeed, during this era, the American economy grew to become the largest in the world and that would not have happened without the help of the federal government.

In the 1880s the Supreme Court ruled on “corporate personhood,” granting corporate enterprises extraordinary Constitutional protections. Titans of industry who preached “laissez-faire” economic dogma did not hesitate to call upon government troops to suppress their workers when they went on strike. And, in 1890, Congress passed yet another tariff on imported goods, this one a whopping 50% tax in order to protect domestic industry.

They called it the “McKinley Tariff” after the Ohio Congressman who sponsored it and it was designed to protect American industry from foreign competition. American businesses preferred their laissez-faire to be situational: no government interference when it suited them; lots of government intervention when they needed it. Six years later, William McKinley was repaid handsomely for his service to big business when they funded his presidential campaign.

Theodore Roosevelt was among a younger generation of politicians and reformers who watched the spectacular rise of industrial capitalism, aided generously by the federal government, with real skepticism. When he accidentally became president in 1901 after McKinley’s assassination, he brought new ideas about the role government ought to play to the White House.

Roosevelt looked at the landscape of American life at the turn of the 20th century and saw that ordinary citizens were more or less powerless in the face of enormous corporations that controlled everything from their wages to the price of consumer goods. The only force in American life strong enough to push back, he concluded, was the federal government.

So if the private sector was going to receive all kinds of support from government, Roosevelt announced that the people would also get protection from corporations through the mechanisms of the federal government. Roosevelt called it his “Square Deal” for the American people, summarized with three “C’s”: conservation of natural resources (against the depredations of timber, mining and other extractive companies); control of corporations; and consumer protection.

This was the bargain TR laid out: big business could continue to grow and prosper and enjoy all sorts of public support, but in exchange they would accept some measure of legal limitations and regulatory controls. If they didn’t play by the new rules, Roosevelt threatened, they might find themselves in court.

Then as now, big business howled at what they saw as over-reaching federal imposition. Most of the rest of us, I suspect, are pretty pleased that our food supply is safe because of the Food and Drug Administration, created by Roosevelt in 1906 after the horrifying conditions of the meat packing industry had been exposed.

Barry Goldwater, Republican Senator from Arizona, and GOP presidential candidate in 1964, famously said that “individual initiative made the desert bloom” in the western part of the country. He was right. Plenty of hard working settlers took that journey (on federally subsidized railroads) to farm hard-scrabble land in the west (which they received through the Homestead Act).

In his ringing call to individuality, however, Goldwater neglected to mention that without the Newlands Reclamation Act of 1902, which created massive and expensive dam and irrigation projects throughout the region and thus provided federally subsidized water to those farmers, no amount of hard work would have made the desert bloom.

Goldwater is regarded as the godfather of today’s anti-government politics because of his angry denunciations of big government and his celebration of individualism. He is the godfather of those politics as well because of his profound historical amnesia.

The Roosevelt Revolution Part II (FDR This Time)

For those Americans angry at the federal government, Franklin Delano Roosevelt is a four-letter word.

There is no question that Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal expanded the scope of government activity and its reach into American life. Nor is there any question that the scale and scope of the crisis he faced when he moved into the White House in 1933 was unprecedented and that FDR had a mandate to do what he did. Americans waited for nearly three years for President Herbert Hoover to do something that might reverse the Great Depression. He failed, and the voters punished him for it.

We can think of FDR’s New Deal—that vast array of initiatives, agencies, and projects they called “alphabet soup” because of all the acronyms—as trying to accomplish two things.

First, FDR wanted to rescue American capitalism from its own cupidity by reforming and stimulating it. The Securities Exchange Commission (SEC), for example, promised to bring oversight and honesty to the stock market in order to avoid the kind of disastrous bubble that triggered the economic collapse in 1929.

Likewise, Roosevelt created the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) because so many ordinary Americans had lost their life savings when their banks failed. Not only did the FDIC insure depositors’ money, which it still does, but in so doing it restored confidence in the entire banking system.

No sector of the economy was stimulated more by the New Deal, however, than housing construction. The Great Depression brought the housing industry to a virtual standstill. As a result thousands were laid off and a housing crisis grew as virtually no new housing units entered the market.

FDR’s solution was to use public money to guarantee private home mortgages through the Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Authority (FHA). This opened up the mortgage market to large numbers of Americans who would otherwise not have been able to purchase a home and, in turn, it created a demand for new housing.

And it worked: by 1970 nearly two-thirds of American families owned their own homes, thanks to the largesse of the federal government, and housing construction had become a major indicator of the health of the overall economy.

There was much that was “new” about the New Deal, but there was much that continued the patterns set out in the 19th century. HOLC and FHA, in the way they promote private home ownership, can be seen as updated versions of the Homestead Act.

The second broad aspect of the New Deal was certainly new.

Under FDR the United States began to develop the rudiments of a social welfare state. When anti-government activists rail against the New Deal it isn’t the mortgage subsidies or the SEC they have in mind, it’s the social welfare programs.

We ought to remember that these programs were modest and that FDR resisted them as long as he could. Only political pressure brought to bear on behalf of the millions of Americans in desperate straits convinced him to initiate employment programs like the Works Progress Administration .

The most enduring of these New Deal social welfare programs is Social Security. This too was an old idea, and the United States was among the last of the industrialized nations to adopt an old-age pension system.

Social Security was denounced by conservatives as paternalistic and insulting because it implied that Americans couldn’t save for their own retirement. Never mind that many Americans in the 1930s didn’t make enough each week to set aside for retirement. Or that Americans over the age of 60 were the poorest demographic group in the nation. Or that many of those Americans had lost all their savings in bank failure.

Republican presidential candidate Alf Landon campaigned in 1936 on a promise to repeal Social Security, though it had only been passed the year before. Conservatives still hate Social Security, and when President George W. Bush vowed to privatize Social Security in 2005 he was channeling his inner Alf Landon. As it happens, Landon lost that election by what was to that point the most lopsided margin in American history.

If many anti-government Americans misunderstand the way the New Deal helped create future economic growth and stability, if they fail to recognize that federal social welfare programs grew only because private charity and local relief funds had all been exhausted, then they also misinterpret Franklin Roosevelt altogether.

FDR was no ideologue, despite the charges leveled against him then and now. He was a pragmatist in the best tradition of American politics. Campaigning in 1932 he told a crowd, “The country needs and, unless I mistake its temper, the country demands bold, persistent experimentation. It is common sense to take a method and try it: If it fails, admit it frankly and try another. But above all, try something.” And that’s what he did.

The fact that he was elected to the presidency four times is perhaps the most important measure of the New Deal’s success.

The Post-War American Government

There were some very strange moments during the 2012 Republican National Convention in Tampa, Florida.

Candidate Mitt Romney and his running mate Congressman Paul Ryan made “small government” the center of their campaign and promised to rein in what they saw as the runaway expansion of federal power under President Obama.

Yet there was former Republican Senator Rick Santorum on stage invoking the memory of his father and how he raised a family while working a government job in the Veterans Administration . Not to be outdone, New Jersey governor Chris Christie got teary-eyed while telling the assembled Republicans about his own father who worked his way through college on the G.I. Bill. When he took the stage, Paul Ryan promised to save Medicare for the next 100 years.

An observer could be forgiven for mistaking all this for, well, the Democratic National Convention. Each of these Republican heavyweights celebrated initiatives created by Democrats and they all involved the expansion of the federal government.

The post-war expansion of government was driven by several factors, not the least of which was the war itself and the Cold War which followed it. Funding for scientific research and education, for the study of “strategic languages,” and even for cultural events all had Cold War rationales. Yet as much asWorld War II and the Cold War changed the landscape, the post-war expansion of government represented important continuities as well.

For example, the G.I. Bill so beloved by Governor Christie provided the financial wherewithal for returning veterans to attend college, thus extending the democratization of higher education set in motion when the Morrill Land Grant Act was passed in 1862.

Likewise, when President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Interstate Highway Act of 1956, he continued the pattern of federal subsidy to large-scale transportation projects that started with the Union and Central Pacific railroads and also included construction of the Panama Canal, another project initiated by President Theodore Roosevelt. Through the Highway Act, the federal government picked up the tab for highway construction to the tune of 90 cents out of every dollar.

Most people angry at government, however, don’t complain about the G. I. Bill or the National Science Foundation (created in 1950) or the interstate highways. Their anger is directed primarily at the civil rights revolution and at the War on Poverty, launched in 1964. For these people Lyndon Baines Johnson is another four-letter word.

For his part, Johnson saw his initiatives as firmly in the American tradition.

When he pushed for the passage of the Civil Rights Act (1964) and the Voting Rights Act (1965), he framed these historic pieces of legislation as completing the process of emancipation and citizenship begun during the Civil War.

And when he declared his War on Poverty he saw himself as completing the work begun by his political hero, Franklin Roosevelt. FDR gave the nation a New Deal; Johnson would turn it into a Great Society.

Medicare, of course, was part of Johnson’s Great Society, extending as it did the Social Security pension with health care coverage. It’s worth remembering that this was opposed bitterly by Ronald Reagan and Barry Goldwater among other conservatives.

In fact, Goldwater made his opposition to Medicare central to his 1964 bid for the presidency. “Having given our pensioners their medical care in kind, why not food baskets” he asked in rhetorical disbelief, “why not public housing accommodations, why not vacation resorts, why not a ration of cigarettes for those who smoke and of beer for those who drink?”

In the end, Medicare did not provide free beer to seniors, but Goldwater lost the election of 1964 by an even greater margin than Landon lost his presidential bid in 1936.

The anti-government backlash against the Great Society, which began in the 1960s, has culminated in the Tea Party and related opposition to President Barack Obama and it has crystallized around the Affordable Care Act.

Whatever one thinks about Obamacare as a policy, much of the opposition to it displays all the historical misunderstanding discussed here. Obamacare opponents, with varying degrees of histrionics, have decried it as an unprecedented intrusion of the federal government into the private sector.

In fact, since the turn of the 20th century, health care has been among the most federally subsidized areas of American life and at a host of levels.

The federal government provided money for hospital construction, especially in the under-served South, and it has provided the training for countless doctors, nurses, and public health professionals. Between 1947 and 1971, to take one example, the Hill-Burton Hospital Survey and Construction Act provided almost $4 billion in federal funds (matched by state money) and added 500,000 hospital beds in almost 11,000 hospital projects.

Likewise, the pharmaceutical industry has relied for years on the basic research sponsored by the National Institutes of Health among other agencies. Between 2003 and 2013, fifteen Americans have won the Nobel Prize in Medicine. Exactly none of them did their path-breaking research in the private sector. They all received public support of one kind or another.

If you’ve ever wondered why the Centers for Disease Control are located in Atlanta and not Washington, the answer is that they started out in 1946 as a federally sponsored malaria control effort, when malaria was still endemic to parts of the South. It’s hard to imagine that the “Sun Belt” would have taken off in the post-war years if all those new arrivals had to spend their time swatting malarial mosquitos.

In fact, the Affordable Care Act itself is not only an outgrowth of the Great Society or even the New Deal. It can trace its origins back to the health care system created after the First World War for veterans returning from that war .

One might not like Obamacare, but its lineage, like so many other government programs, is all-American.

Why All the Fuss?

Given the history of the federal role in fostering the economy, education, health care, transportation, communication and more, why do so many Americans seem to resent our government with such vehemence?

One answer is that Americans like their government hidden from them. Steeped in myths of rugged individualism, we don’t like to believe that we’ve had any help achieving what we’ve achieved.

So while Americans have never been eager to support public housing for those who need it, few of them thank the federal government for subsidizing the mortgage on their own house. Likewise, these people see funding for public transportation as a waste of money even as they drive down interstate highways extravagantly paid for with federal money.

When Lincoln Center officials renamed the New York State Theater after David Koch, they not only honored a donor but they hid from the public the public source of the theater in the first place. Come to think of it, perhaps that’s exactly what Koch intended.

Another reason Americans are hostile to their own government is our conflicted views about race and class. If we’ve achieved our success all on our own, then those who do need more obvious forms of government help must be failures of some kind. More to the point, they suck up my tax dollars.

Government programs that aid the have-nots appear to many Americans to reward laziness and irresponsibility, like Aid to Families with Dependent Children. In contrast, programs which benefit middle-class people are seen as something they have worked hard to deserve, like deducting the interest payments on your mortgage on your federal taxes. Bluntly put: Americans don’t like government when it works for the poor (even if Teddy Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson thought it should).

Nor, it must be said just as bluntly, do they like government when it is designed to benefit African Americans. Barry Goldwater campaigned just as energetically against the Civil Rights Act in 1964 as he did against Medicare. In so doing he created the coalition that joined segregationist bigots with anti-government zealots, the one that helped elect Richard Nixon and then Ronald Reagan. Now that a black man is the face of the federal government, the worst nightmare for this group of Americans has become real.

Those cheering GOP conventioneers in Tampa point to a final reason why Americans don’t like big government. It has become, over and over again, the victim of its own success. After all, before the Republican Party supported the G. I. Bill and Medicare, it opposed them. Just like conservatives opposed the SEC and the FDIC in an earlier generation, and they opposed the FDA a generation before that.

Despite the rhetoric we are used to hearing that government programs are wasteful failures, the record of many of them is quite successful. We did create the greatest system of higher education in the world, and we did build 40,000 miles of interstate highway, and we did raise seniors out of poverty. The list could go on.

Yet because so many of these programs are hidden from sight, and because they have worked as effectively as they have, we have taken them for granted. A kind of familiarity that has bred a bitter contempt.

One Final Scene

On August 28, 2010 media demagogue Glenn Beck sponsored a rally in Washington, a quasi-religious revival to “restore America.”

The ironies were thick on the ground that day, though I suspect few of the assembled thousands noticed them. Beck issued his call for restoration on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial – the shrine to the man who expanded federal power dramatically – and he did so on the 47th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s March on Washington. Beck was shamelessly trying to invoke the moral authority of that event, oblivious, apparently, to the fact that King and others came to Washington to demand federal action to advance the civil rights agenda.

Most of all, however, Beck and the thousands who came to restore America all demonstrated a fundamental misunderstanding of the role the federal government has played from the very beginning of the nation: to promote the general welfare as each generation has defined that task.

We can and should have debates over what is and is not appropriate for the federal government to do in American life. But those debates can only be fruitful if we wake up from the historical amnesia we seem to be suffering currently.

In the meantime, keep your government hands off my Medicare.

Brian Balogh, A Government Out of Sight: The Mystery of National Authority in 19th Century America (2009)

Steven Conn, ed., To Promote the General Welfare: The Case for Big Government (Oxford UP 2012)

Richard John, Network Nation: Inventing American Telecommunications (2010)

Paul Light, Government's Greatest Achievements: From Civil Rights to Homeland Defense (2002)